Introduction

The pineal gland is a small endocrine gland (10 to 14 mm) located in the midline of the brain, at the superior aspect of the posterior border of the third ventricle. In the coronal view, the gland is located below the splenium of the corpus callosum and above and posterior to the tectum of the midbrain.[1] Its principal function is to secrete the hormone melatonin and receive information from the environment about the light-dark cycle to feedback the central nervous system.[2]

The principal cells of the pineal gland are the pinealocytes (pineal parenchymal cells). Multiple pathologies are associated with this region due to the variety of cells and structures located adjacent to the pineal gland. Tumors of the pineal gland are classified into those arising from the pineal parenchyma, germ cell tumors, and lesions arising from adjacent structures.[1] Other lesions adjacent to the gland are astrocytoma, oligodendroglioma, glial cyst (pineal cyst), meningioma, arachnoid cyst, ependymoma, chemodectoma, epidermoid, dermoid, metastasis, aneurysm of the vein of Galen, arteriovenous malformation, and cysticercosis. This review will discuss those tumors which arise from the gland proper and germ cell tumors.

Important anatomical structures adjacent to the pineal gland include:[3]

- Anteriorly: third ventricle (pineal recess)

- Anterosuperiorly: habenular nuclei

- Superiorly: internal cerebral veins, the vein of Galen (posteriorly), stria medullaris, splenium of the corpus callosum and velum interpositum

- Posteroinferiorly: superior cerebellar cistern

- Inferiorly: superior colliculi of the midbrain

- Anteroinferiorly: posterior commissure

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The etiology of pineal gland tumors is based on the histopathological classification.

- Pineal parenchymal tumors

- Pineocytoma

- Pineal parenchymal tumor with intermediate differentiation

- Pineoblastoma

- Papillary tumor of the pineal region

- Germ cell tumors

- Germinomatous germ cell tumors:

- Pineal germinoma

- Nongerminomatous germ cell tumors:

- Choriocarcinoma

- Embryonal carcinoma

- Yolk sac tumor (endodermal sinus tract tumor)

- Immature teratoma

- Mature teratoma

Epidemiology

Tumors of the pineal area are rare and account for 1% of all intracranial tumors in adults. However, they account for up to 8% in children. Due to the diversity of tumors in this area, the characteristics and epidemiology vary greatly. Will describe each according to the WHO 2016 classification.[4]

Pineocytoma

Pineocytomas can be seen at any age, but mostly occur in adults from 20 to 60 years of age.[4] Pineocytomas are more frequently encountered in females (M:F 0.6 to 1).[4] They account for 14-30% of pineal parenchymal tumors and are mature well-differentiated tumors.[4][5]

WHO grade 1

Pineal Parenchymal Tumor with Intermediate Differentiation

These tumors are mainly seen in middle-aged adults from 20 to 70 years of age. They have a slight female preference, similar to that of pineocytomas.[4] They account for 20-62% of pineal parenchymal tumors, making them one of the most common intrinsic pineal tumors.[4][5]

WHO grade 2/3

Papillary Tumor of the Pineal Region

Papillary tumors have the broadest range of ages in the pineal parenchymal tumors, seen from 1-70 years of age, with most cases in mid-age.[6][7] They have no gender preference.[4]

WHO grade 2/3[5]

Pineoblastoma

Pioneoblastoma is the most aggressive pineal parenchymal tumor. They account for 24 to 50% of all pineal parenchymal tumors.[5][7] They have a slight female predilection (M:F 0.7 to 1) and are typically seen in young children.[4] Patients with hereditary bilateral retinoblastoma are prone to suprasellar or pineal neuroblastic tumors, a condition called trilobar retinoblastoma, seen in up to 5% of pineoblastomas.[8][9]

WHO grade 4

Germinoma

It can account for 50% of pineal parenchymal tumors. It is much more common in males (M:F of 13 to 1). Most are 20 years or younger at the time of evaluation. They are commonly diagnosed with CSF (cerebrospinal fluid) tumor markers. They have elevated placental alkaline phosphatase and beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (b-HCG).[10]

WHO Classification (9064/3) - Malignant[4]

Choriocarcinoma

The uncommon tumor which accounts for 5% of pineal region masses and 10% of intracranial germ cell tumors.[11][12] They can be found in the pineal and suprasellar regions. They have increased CSF and plasma b-HCG.[12][13]

WHO Classification (9100/3) - Malignant[4]

Embryonal Carcinoma

The uncommon tumor which accounts for less than 5% of pineal region masses and 10% of intracranial germ cell tumors.[14] It has a propensity for metastasis.[15] Mixed germ-cell tumors can have a component of embryonal carcinoma, which confers a worse prognosis. Elevated tumor markers can be seen in CSF, such as alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) and b-HCG. [14]

Who Classification (9070/3) - Malignant[4]

Yolk Sac Carcinoma (Endodermal Sinus)

Pineal yolk sac tumors are a rare manifestation of extragonadal yolk sac tumor. They make one of the smallest fractions of intracranial germ cell tumors. They sometimes have an association with Trisomy 21 (Down syndrome).[16][17][18] CSF studies show elevated levels of AFP but are non-diagnostic. [16]

WHO Classification (9071/3) - Malignant [4]

Immature/Mature Teratoma

An uncommon tumor; however, it is the most common fetal intracranial neoplasms (26 to 50% of fetal brain tumors). [19][20] Can be mature or immature, which greatly changes the prognosis. Gross total resection of a mature teratoma is considered curative.[19][20]

Immature: WHO Classification (9080/3) - Malignant[4]Mature: WHO Classification (9080/0) - Benign[4]

Pathophysiology

The pineal gland forms during the seventh week of gestation.[21] In humans, the principal function of the pineal gland is the production of melatonin, which modulates the sleep patterns. It is also associated with puberty and reproductive functions.

Tumors of the pineal region are diverse in origin due to the proximity of multiple anatomical structures. The pineal gland is commonplace for the sequestration of embryonic germ cells. Thus, germ cell tumors are among the most common pathologies found in this area.[22]

Germ cell tumors typically occur sporadically.[23] However, there is an association with Klinefelter syndrome, Down syndrome, and Neurofibromatosis type 1.[18][24][25][26]

Pineal region tumors are generally classified as:

- Pineal parenchymal tumors

- Germ cell tumors

- Adjacent cell tumors (astrocytes, arachnoid cap cells)

- Metastases

Histopathology

Pineocytoma

Comprised of small cells similar in appearance to normal pinealocytes, arranged in sheets; pineocytomatous pseudorosettes are characteristic and not seen in healthy pineal gland tissue.[4][6] Pineocytomas do not have a well-formed blood-brain barrier and, as such, enhance vividly with contrast.[27] Synaptophysin: positive; neurofilament protein: positive, neuron-specific enolase: positive, other neuronal markers (Tau protein, chromogranin-A, 5-HT): variable, neuronal nuclei: negative

Pineal Parenchymal Tumors with Intermediate Differentiation

Characteristically show two distinct microscopic patterns.[4] The lobulated pattern shows poorly defined lobules, separated from each other by large fibrous vessels. The diffuse pattern is reminiscent of oligodendrogliomas or central neurocytomas, with the large pineocytomatous rosettes characteristic of pineocytomas not evident. Synaptophysin: positive, neurofilament protein: variable, neuronal nuclei: negative

Papillary Tumor of the Pineal Region

Demonstrate variable morphology, from solid to predominantly papillary, reminiscent of ependymomas, including evidence of ependymal rosettes.[28] Areas of necrosis are sometimes present.[4][7][28] Cytokeratins (AE1/3, CAM5.2, KL1, CK18): positive, S100: positive, vimentin: positive, transthyretin: positive, neuron-specific enolase: positive, microtubule-associated protein 2: positive, glial fibrillary acidic protein: variable

Pineoblastoma

Tightly packed small round blue cells (high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio). Homer Wright rosettes and Flexner-Wintersteiner rosettes are occasionally seen.[4] Areas of necrosis are frequently encountered.[4] The mitotic rate is usually high. Synaptophysin: positive, SMARCB1: positive, other neuronal markers (neuron-specific enolase, neurofilament protein, and chromogranin-A): variable

Germinoma

Germinomas originate from primordial germ cells, similar to those in gonadal germinomas. Cells have large nuclei with prominent nucleoli. Lymphocytic infiltration is common. On immunohistochemistry, they stain for placental alkaline phosphatase.[10] CSF samples can show placental alkaline phosphatase and b-HCG.[10]

History and Physical

Clinical presentations for all tumors of the pineal region are secondary to obstructive hydrocephalus and compression of the tectum. Thus, regardless of the pathology, the physical exam findings will similar for all the tumors.

- Hydrocephalus:

- History: Headache, nausea, failure to thrive, macrocephaly, blurry vision, sleepiness, drowsiness, or coma.

- Exam:

- Cushing’s triad; hypertension, bradycardia, and irregular respirations

- Bilateral optic nerve swelling

- Bilateral sixth nerve palsy

- Compression of tectum (Parinaud syndrome):

- History: Difficulty walking upstairs, diplopia

- Exam:

- Paralysis of upwards gaze and conjugate downward gaze

- Compression of the vertical gaze center at the rostral interstitial nucleus of medial longitudinal fasciculus

- Light-near dissociation

- Compression of the pretectal nucleus in the superior colliculus

- Convergence-retraction nystagmus and eye-lid retraction (Collier sign)

- Damage to the supranuclear fibers of the third nerve at the posterior midbrain.

Evaluation

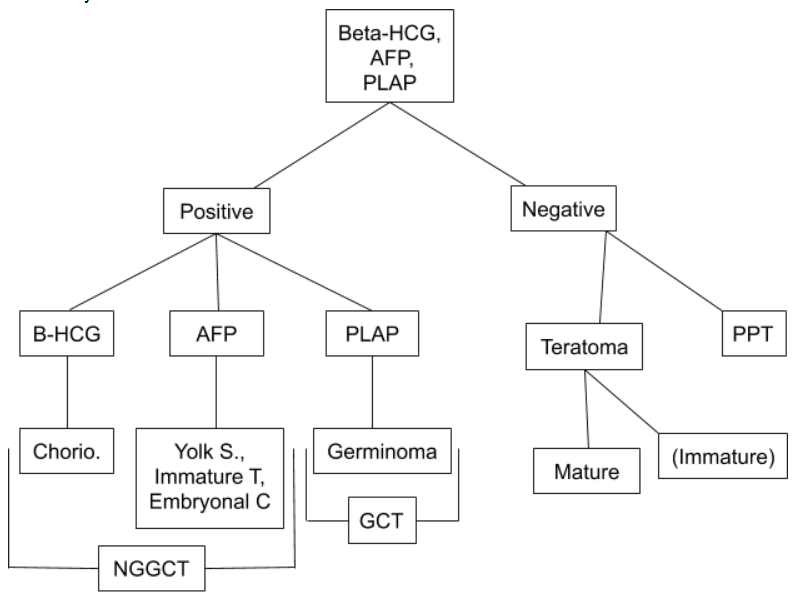

Serum tumor markers are indicated when specific tumors are suspected and include AFP, b-HCG, and placental alkaline phosphatase.

CSF analysis, which can be obtained by lumbar puncture if there is no hydrocephalus or during endoscopy, is useful for most tumors. (See figure)

Imaging:

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with and without gadolinium enhancement is the gold standard of evaluation for pineal region tumors. However, if not available, head computed tomographic (CT) scan, angiography, and ultrasound (in infants) play a role.

Normal findings on neuroimaging of the pineal gland:

- CT scan:[29] Calcification is typical in the adult pineal gland. In children under the age of 5 years, calcification is not present. Calcification of the pineal gland reaches a plateau at about 30 years of age.

- MRI:[21] The gland is similar to the intensity of the gray matter and appears as a small nodule of tissue in the posterior aspect of the third ventricle. It is avidly enhancing with gadolinium due to being outside the blood-brain barrier, and calcifications are often seen.

Brain MRI will show homogenous enhancing, except those presenting with heterogeneous cellularity. Dense tumors, like pineoblastoma and germinomas, will have restricted diffusion on the diffusion-weighted images. On the other hand, pineal cysts are non-enhancing and usually have a thin wall; therefore, a thick wall excludes a cyst.

Calcifications are often present and easier to be identified in a head CT scan, and can sometimes point in the right direction of diagnosis. Pineal parenchymal tumors (e.g., pineocytoma or pineoblastoma) tend to peripherally disperse calcification, whereas germ cell tumors tend to engulf the calcifications. An easy way to remember this is that pineoblastomas tend to blast the calcifications apart.

Many tumors of the pineal region may cause local or distant seeding. Thus, full spine MRI may be considered as part of the initial evaluation. Local invasion and remote seeding are significant for prognosis and may change initial management and adjuvant therapy drastically.

Findings that can point to worse prognosis include local invasion, CSF seeding, and extensive peritumor edema.

- Local invasion can be seen in pineoblastomas and most germ cell tumors.

- CSF seeding can be seen in pineoblastomas (distal seeding is most common) and in germinomas (proximal seeding is most common).

Treatment / Management

Imperative to follow treatment algorithms to ensure adequate diagnosis and treatment.

- If hydrocephalus absent:

- Tumor markers obtained (serum and CSF).

- If positive, treatment based on most likely pathology (See figure)

- If negative tissue diagnosis is necessary:

- Biopsy (stereotactic, endoscopic, open).

- Resection (based on preliminary radiographic findings or pathology findings)

- Final management is based on pathology.

- If hydrocephalus present:

- CSF fluid diversion; best option is an endoscopic third ventriculostomy (ETV)

- Always attempt endoscopic biopsy during ETV

- Final management is based on pathology

Endoscopic third ventriculostomy:

- It is performed by fenestration of the floor of the third ventricle, thus forming a passage between the third ventricle and prepontine cisterns.

- In most cases, a right frontal burr hole (just anterior to Kocher’s point) is performed, and the neuro endoscope is advanced until the ipsilateral lateral ventricle is reached. Through the ipsilateral foramen of Monro, the floor of the third ventricle (tuber cinereum) is fenestrated and expanded to permit adequate CSF flow.

- A biopsy is obtained from the posterior aspect of the third ventricle.

- If endoscopic third ventriculostomy fails, the definitive treatment is a ventricular shunt placement.

- ETV success score:[30]

- ETV success score uses three variables for its calculation; age, cause of hydrocephalus, and previous ventricular shunt placement. To calculate the success score, one must add up the percentage of success for each variable. The lowest score is 0% and the highest at 90%.

- Age:

- <1 month = 0%

- 1 to 6 months = 10%

- 6 months to 1 year = 30%

- 1 to 10 years = 40%

- >10 years = 50%

- Cause of hydrocephalus:

- Post-infectious = 0%

- Myelomeningocele, intraventricular hemorrhage, and non-tectal tumor = 20%

- Tectal tumor, aqueductal stenosis, or other = 30%

- Previous ventricular shunt placement:

- Yes = 0%

- No = 10%

Definite treatment is based on the pathology:

- Surgical resection:

- All pineal parenchymal tumors

- Mature teratoma

- Residual tumor after chemotherapy + radiotherapy (so-called “second-look surgery”)

- Radiotherapy (reserved for patients > 3 years old):

- Germinoma

- Chemotherapy plus radiotherapy (chemotherapy alone if <3 years old):

- Adjuvant chemotherapy plus radiotherapy are given to all tumors except pineocytoma and mature teratoma if complete resection is achieved.

- All non-germinomatous germ cell tumors

- Germinomatous germ cell tumors if <3 years old.

Surgical approach to the pineal region is chosen based on the specific location of pathology and surgeon preference:

- Paramedian infratentorial supracerebellar resection:[31]

- Useful for all pineal region tumors except for large tumors that extend laterally and inferiorly.

- Left-sided suboccipital craniotomy is performed to protect the torcula and the often more dominant right-sided veins and dural sinuses, including the transverse sinus.

- Most flexible approach for resection of most pineal region tumors.

- Midline infratentorial supracerebellar resection:[32]

- They are traditionally used for exposing pineal region tumors.

- Performed via a bilateral midline suboccipital craniotomy.

- Limitations of this approach include limited lateral or inferior visualization caused by the angle of the tentorium and the obstructive apex of the culmen, respectively.

- Almost all midline bridging vermian veins are invariably sacrificed.

- Occipital transtentorial resection:[33]

- Particularly useful for large pineal region tumors that extend laterally and inferiorly.

- Performed through a unilateral occipital craniotomy.

- Limitations of this approach include difficulty with anatomic orientation, the need to divide the tentorium, and the possibility of a homonymous hemianopia from occipital lobe retraction.

It is crucial to screen the full neuroaxis with all pineal region tumors. Prognosis and treatment dramatically vary depending on the CSF spread of the tumor. Distant CSF seeding (except for germinoma), and drop metastasis have a poor prognosis. MRIs of the brain, cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine with and without contrast is required for adequate screening of the neuraxis. Spinal radiotherapy as a prophylactic treatment is controversial.

Differential Diagnosis

- Cystic non-neoplastic lesions:

- pineal cysts

- cavum veli interpositum

- arachnoid cyst

- Pineal parenchymal tumors:

- pineocytoma

- pineal parenchymal tumor with intermediate differentiation

- pineoblastoma

- papillary tumor of the pineal region

- Germ cell tumors:

- pineal germinoma

- embryonal carcinoma

- choriocarcinoma

- teratoma (mature/immature)

- yolk sac tumor

- Tumors also encountered in the pineal region:

- astrocytoma

- meningioma

- cerebral metastases

- Pineal gland metastases

- Vascular lesions:

- vein of Galen aneurysm/malformation

- internal cerebral vein thrombosis

Prognosis

Pineocytoma:

- Relatively good prognosis.

- If treated surgically, they have an excellent prognosis when complete resection is achieved (which is most of the time as they are well-circumscribed lesions).

- Five-year survival of 86% to 91%.[4] Local recurrent and even CSF metastases are rare.[7]

Pineal parenchymal tumor with intermediate differentiation:

- Prognosis is between that of pineocytoma and pineoblastoma.

- They are more likely to present with localized disease.

- Median overall survival of 165 months (vs. 77 months for pineoblastoma) with a median progression-free survival of 93 months (vs. 46 months for pineoblastoma).[4]

Pineoblastoma:

- It is the most aggressive of the pineal parenchymal tumors.

- Median overall survival time, reaching 4 to 8 years.[4]

- The 5-year overall survival rates vary from 10% to 81%.[4]

- Prognosis is negatively affected based on:

- Dissemination of disease at the time of diagnosis

- Young patient age.

- Partial surgical resection.

- Chemotherapy treatment and the possible addition of stem cells can provide a better outcome.[9]

Papillary tumor of the pineal region:

- Local recurrences often affect prognosis.

- The 5-year overall and progression-free survival rate were 73% and 27%, respectively.[4]

- Gross total resection and younger patient age are associated with improved overall survival; radiotherapy and chemotherapy had no significant impact.[4]

- Screening of the entire neural axis is required as CSF dissemination occurs in up to 7% of cases.

Germinoma:

- Remarkably radiosensitive, with long-term survival rates of > 90% after craniospinal irradiation.[10][34]

- The addition of chemotherapy to treatment regimens may provide comparable tumor control at lower radiation doses and field volumes.

- The leptomeningeal or intraventricular spread is not uncommon at the time of diagnosis, occurring in 13%.

Mature teratoma:

- Curable by complete surgical excision.[4]

Immature teratoma:

- Along with germinoma, occupy an intermediate position in terms of biological behavior.[4]

- The size and location determine prognosis.

Embryonal carcinoma, choriocarcinoma, and yolk sac tumor (endodermal sinus):

- These are the most aggressive germ cell tumors.[4]

- Survival rates as high as 60-70% can be achieved with combined chemotherapy and irradiation. Local recurrence and CSF dissemination are the usual patterns of progression.

Complications

The tumor can lead to various complications:

- Hypothalamic and endocrine dysfunction

- Extraocular movement dysfunction

- Hemorrhage

- Venous infarct

- Seizures

- Hemiparesis

- Ataxia

Consultations

The following consultations should be obtained to appropriately diagnose and treat the tumor:

- Neurosurgeon

- Neurologist

- Pediatrician

- Endocrinologist

- Opthalmology

- Hematologist oncologist

- Radiation oncologist

Deterrence and Patient Education

Any of these tumors can recur even after long periods; therefore, prolonged follow-up of patients is necessary. Those patients with cerebral shunts also need lifelong evaluations. As the prognosis and treatment are dependent on the histology, patients and parents need to be counseled about their particular tumor and the requirement of adjuvant therapies.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Prognosis and outcomes for pineal tumors depend on the histology and treatment received. An interprofessional team of specialists that include a pediatrician, endocrinologist, neurologist, neurosurgeon, neuro-ophthalmologist, and intensivist must work together to provide the best care for patients with pineal tumors.

Neuroradiologists can help with the radiological identification of a specific tumor, as several of them show peculiar characteristics. Cytologists can help with the identification of tumor markers that can define particular management strategies. Nurses and pharmacists will help the patient in the postoperative period.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Smith AB, Rushing EJ, Smirniotopoulos JG. From the archives of the AFIP: lesions of the pineal region: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2010 Nov:30(7):2001-20. doi: 10.1148/rg.307105131. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21057132]

Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, Boyce A, Chrousos G, Corpas E, de Herder WW, Dhatariya K, Dungan K, Hofland J, Kalra S, Kaltsas G, Kapoor N, Koch C, Kopp P, Korbonits M, Kovacs CS, Kuohung W, Laferrère B, Levy M, McGee EA, McLachlan R, New M, Purnell J, Sahay R, Shah AS, Singer F, Sperling MA, Stratakis CA, Trence DL, Wilson DP, Arendt J, Aulinas A. Physiology of the Pineal Gland and Melatonin. Endotext. 2000:(): [PubMed PMID: 31841296]

Yamamoto I. Pineal region tumor: surgical anatomy and approach. Journal of neuro-oncology. 2001 Sep:54(3):263-75 [PubMed PMID: 11767292]

Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, von Deimling A, Figarella-Branger D, Cavenee WK, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Kleihues P, Ellison DW. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Acta neuropathologica. 2016 Jun:131(6):803-20. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1545-1. Epub 2016 May 9 [PubMed PMID: 27157931]

Osborn AG, Salzman KL, Thurnher MM, Rees JH, Castillo M. The new World Health Organization Classification of Central Nervous System Tumors: what can the neuroradiologist really say? AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology. 2012 May:33(5):795-802. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2583. Epub 2011 Aug 11 [PubMed PMID: 21835942]

Nishioka H, Inoshita N. New WHO classification of pituitary adenomas (4th edition): assessment of pituitary transcription factors and the prognostic histological factors. Brain tumor pathology. 2018 Apr:35(2):57-61. doi: 10.1007/s10014-017-0307-7. Epub 2018 Jan 9 [PubMed PMID: 29318396]

Dumrongpisutikul N, Intrapiromkul J, Yousem DM. Distinguishing between germinomas and pineal cell tumors on MR imaging. AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology. 2012 Mar:33(3):550-5. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2806. Epub 2011 Dec 15 [PubMed PMID: 22173760]

Rodjan F, de Graaf P, Moll AC, Imhof SM, Verbeke JI, Sanchez E, Castelijns JA. Brain abnormalities on MR imaging in patients with retinoblastoma. AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology. 2010 Sep:31(8):1385-9. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2102. Epub 2010 Apr 22 [PubMed PMID: 20413604]

de Jong MC, Kors WA, de Graaf P, Castelijns JA, Kivelä T, Moll AC. Trilateral retinoblastoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet. Oncology. 2014 Sep:15(10):1157-67. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70336-5. Epub 2014 Aug 7 [PubMed PMID: 25126964]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKilgore DP, Strother CM, Starshak RJ, Haughton VM. Pineal germinoma: MR imaging. Radiology. 1986 Feb:158(2):435-8 [PubMed PMID: 3941869]

Bazot M, Cortez A, Sananes S, Buy JN. Imaging of pure primary ovarian choriocarcinoma. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2004 Jun:182(6):1603-4 [PubMed PMID: 15150023]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAllen SD, Lim AK, Seckl MJ, Blunt DM, Mitchell AW. Radiology of gestational trophoblastic neoplasia. Clinical radiology. 2006 Apr:61(4):301-13 [PubMed PMID: 16546459]

Takeuchi M, Matsuzaki K, Uehara H, Yoshida S, Nishitani H, Shimazu H. Pathologies of the uterine endometrial cavity: usual and unusual manifestations and pitfalls on magnetic resonance imaging. European radiology. 2005 Nov:15(11):2244-55 [PubMed PMID: 16228215]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHorowitz MB, Hall WA. Central nervous system germinomas. A review. Archives of neurology. 1991 Jun:48(6):652-7 [PubMed PMID: 2039390]

Smirniotopoulos JG, Rushing EJ, Mena H. Pineal region masses: differential diagnosis. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 1992 May:12(3):577-96 [PubMed PMID: 1609147]

Tan HW, Ty A, Goh SG, Wong MC, Hong A, Chuah KL. Pineal yolk sac tumour with a solid pattern: a case report in a Chinese adult man with Down's syndrome. Journal of clinical pathology. 2004 Aug:57(8):882-4 [PubMed PMID: 15280413]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNakashima T, Nishimura Y, Sakai N, Yamada H, Hara A. Germinoma in cerebral hemisphere associated with Down syndrome. Child's nervous system : ChNS : official journal of the International Society for Pediatric Neurosurgery. 1997 Oct:13(10):563-6 [PubMed PMID: 9403208]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChik K, Li C, Shing MM, Leung T, Yuen PM. Intracranial germ cell tumors in children with and without Down syndrome. Journal of pediatric hematology/oncology. 1999 Mar-Apr:21(2):149-51 [PubMed PMID: 10206462]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSandow BA, Dory CE, Aguiar MA, Abuhamad AZ. Best cases from the AFIP: congenital intracranial teratoma. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2004 Jul-Aug:24(4):1165-70 [PubMed PMID: 15256635]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBuetow PC, Smirniotopoulos JG, Done S. Congenital brain tumors: a review of 45 cases. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 1990 Sep:155(3):587-93 [PubMed PMID: 2167004]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSumida M, Barkovich AJ, Newton TH. Development of the pineal gland: measurement with MR. AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology. 1996 Feb:17(2):233-6 [PubMed PMID: 8938291]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceUeno T, Tanaka YO, Nagata M, Tsunoda H, Anno I, Ishikawa S, Kawai K, Itai Y. Spectrum of germ cell tumors: from head to toe. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2004 Mar-Apr:24(2):387-404 [PubMed PMID: 15026588]

Gempt J, Ringel F, Oexle K, Delbridge C, Förschler A, Schlegel J, Meyer B, Schmidt-Graf F. Familial pineocytoma. Acta neurochirurgica. 2012 Aug:154(8):1413-6. doi: 10.1007/s00701-012-1402-5. Epub 2012 Jun 15 [PubMed PMID: 22699425]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKaido T, Sasaoka Y, Hashimoto H, Taira K. De novo germinoma in the brain in association with Klinefelter's syndrome: case report and review of the literature. Surgical neurology. 2003 Dec:60(6):553-8; discussion 559 [PubMed PMID: 14670679]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHashimoto T, Sasagawa I, Ishigooka M, Kubota Y, Nakada T, Fujita T, Nakai O. Down's syndrome associated with intracranial germinoma and testicular embryonal carcinoma. Urologia internationalis. 1995:55(2):120-2 [PubMed PMID: 8533196]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWong TT, Ho DM, Chang TK, Yang DD, Lee LS. Familial neurofibromatosis 1 with germinoma involving the basal ganglion and thalamus. Child's nervous system : ChNS : official journal of the International Society for Pediatric Neurosurgery. 1995 Aug:11(8):456-8 [PubMed PMID: 7585682]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFakhran S, Escott EJ. Pineocytoma mimicking a pineal cyst on imaging: true diagnostic dilemma or a case of incomplete imaging? AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology. 2008 Jan:29(1):159-63 [PubMed PMID: 17925371]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceChang AH, Fuller GN, Debnam JM, Karis JP, Coons SW, Ross JS, Dean BL. MR imaging of papillary tumor of the pineal region. AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology. 2008 Jan:29(1):187-9 [PubMed PMID: 17925365]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBeker-Acay M, Turamanlar O, Horata E, Unlu E, Fidan N, Oruc S. Assessment of Pineal Gland Volume and Calcification in Healthy Subjects: Is it Related to Aging? Journal of the Belgian Society of Radiology. 2016 Feb 1:100(1):13. doi: 10.5334/jbr-btr.892. Epub 2016 Feb 1 [PubMed PMID: 30038974]

Labidi M, Lavoie P, Lapointe G, Obaid S, Weil AG, Bojanowski MW, Turmel A. Predicting success of endoscopic third ventriculostomy: validation of the ETV Success Score in a mixed population of adult and pediatric patients. Journal of neurosurgery. 2015 Dec:123(6):1447-55. doi: 10.3171/2014.12.JNS141240. Epub 2015 Jul 24 [PubMed PMID: 26207604]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKulwin C, Matsushima K, Malekpour M, Cohen-Gadol AA. Lateral supracerebellar infratentorial approach for microsurgical resection of large midline pineal region tumors: techniques to expand the operative corridor. Journal of neurosurgery. 2016 Jan:124(1):269-76. doi: 10.3171/2015.2.JNS142088. Epub 2015 Aug 14 [PubMed PMID: 26275000]

Rey-Dios R, Cohen-Gadol AA. A surgical technique to expand the operative corridor for supracerebellar infratentorial approaches: technical note. Acta neurochirurgica. 2013 Oct:155(10):1895-900. doi: 10.1007/s00701-013-1844-4. Epub 2013 Aug 28 [PubMed PMID: 23982230]

Moshel YA, Parker EC, Kelly PJ. Occipital transtentorial approach to the precentral cerebellar fissure and posterior incisural space. Neurosurgery. 2009 Sep:65(3):554-64; discussion 564. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000350898.68212.AB. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19687701]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMootha SL, Barkovich AJ, Grumbach MM, Edwards MS, Gitelman SE, Kaplan SL, Conte FA. Idiopathic hypothalamic diabetes insipidus, pituitary stalk thickening, and the occult intracranial germinoma in children and adolescents. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 1997 May:82(5):1362-7 [PubMed PMID: 9141516]