Introduction

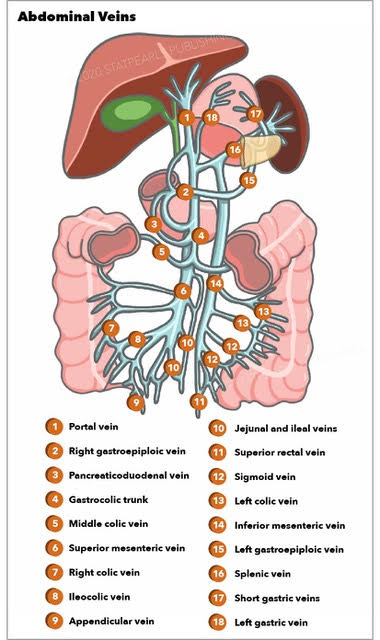

Portal vein obstruction is a common complication of several metabolic and autoimmune diseases. It is most commonly the result of thrombosis of the portal vasculature, but it can also result from malignancies. Due to the vast range of diseases that result in portal vein obstruction, understanding the common causes, pathophysiologies, and relevant management is key to treating patients suffering from this disease. See Image. Abdominal Vein Anatomy. Most cases are caused by portal vein thrombosis and the rest are related to malignancies. This review focuses on “bland” portal vein obstruction (also called portal vein thrombosis) and not on portal vein obstruction due to tumor invasion.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The causes of portal vein thrombosis can be divided into two categories: inherited and acquired.

Inherited

- Factor V Leiden mutation

- Prothrombin gene mutation

- Anti-thrombin III deficiency

- Protein C deficiency

- Protein S deficiency

Acquired

- Lupus anticoagulant syndrome

- Liver disease

- Iatrogenic

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation

- Burns

- Sepsis

- Malignancy

- Myeloproliferative disorders

- Peripartum

- Oral contraceptives

- Inflammatory states

Rare iatrogenic causes include bariatric surgery, radiofrequency ablation (RFA) for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), or fine-needle aspiration of pancreatic cancer.[1]

In children, the most common cause of portal vein obstruction is an intra-abdominal infection. Placement of an umbilical catheter in neonates is also a common cause of the disorder. Other causes include congenital abnormalities of the portal venous system.

In adults, the vast majority of cases are due to cirrhosis, followed by neoplasms. Tumors can compress, invade or induce a hypercoagulable state leading to portal vein thrombosis. About 10% of cases are idiopathic.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of portal vein occlusion varies in different populations. In patients with cirrhosis or portal hypertension, it is estimated to be anywhere between 1.6% and 15.8%.[1] The incidence is higher where the cirrhosis results from alcohol use disorder or Hepatitis B infection. The prevalence is as low as 1% in patients with compensated liver cirrhosis,[2] while as high as 25% in patients awaiting a liver transplant.[3] Possible causes for the higher incidence in liver transplant patients include advanced underlying disease, immobility due to possibly worse ascites, and a higher degree of imbalance of clotting factors.

Pathophysiology

The portal vein forms at the junction of the superior mesenteric and splenic veins, just behind the head of the pancreas. The vein can be obstructed at any point in its course. In rare cases, thrombosis of the splenic vein extends into the portal vein, a scenario commonly encountered in chronic pancreatitis.

The pathophysiology of the obstruction depends upon the cause. In liver cirrhosis patients, endothelial dysfunction is implicated along with an imbalance of coagulation factors leading to a net hypercoagulable state. Blood samples of cirrhotic patients have been found to have high quantities of thrombin.[4]

Similarly, stasis or low portal velocity has also been found to have an association with portal vein thrombosis.[1] There could be an associated link with the use of beta blockers, but the results of a study demonstrating this link are yet to be replicated.

In cancer patients, the obstruction can occur due to thrombosis (from stasis or hypercoagulability caused by cancer) or direct invasion from a growing tumor.

Obstruction of the portal vein usually does not affect liver function, unless the organ is diseased to begin with. In most cases, once the portal vein is thrombosed, collaterals develop within 2-10 weeks and are responsible for the majority of complications. Ascites is also a common complication of portal vein thrombosis. If the thrombus extends into the mesenteric vein, it can lead to bowel ischemia.

History and Physical

Patients typically present with signs of portal hypertension. Although individual presentations vary depending on the cause, patients commonly demonstrate[5]:

- Abdominal pain (91%)

- Fever (53%)

- Ascites (38%)

Depending upon the severity of the disease, splenomegaly will present in about 75 to 100% of patients. In patients with liver cirrhosis as the primary cause, signs such as spider angiomata and palmar erythema may be evident. If there has been longstanding portal hypertension, collaterals might be clinically evident with caput-medusae (umbilical veins), hemorrhoids (rectal veins), or in patients presenting with upper gastrointestinal bleeding from enlarged esophageal veins (varices).

Ascites is not uncommon in patients with portal vein obstruction.

In cases where malignancies are the primary cause, either from thrombus formation or direct invasion, clinical manifestations of the neoplasm could be prominent. In cases of pancreatic carcinoma, fatigue and jaundice are usually present. Similarly, jaundice is also present in hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma. In patients with jaundice, associated pruritis is a common finding as well.

Decision-making on best treatment options for patients with PVT can be based upon separating patient status into either acute PVT or chronic PVT. Patients with chronic PVT are more limited in treatment options and may only derive benefit from surgical shunt formation or from a conservative medical approach aimed at improving quality of life but not curing the disease. The rationale for this is

- that chronic thrombus is less likely to respond to either mechanical maceration or to chemical (medicinal) lysis,

- that adequate flow is less likely to be re-established in the system if a vein is scarred down from thrombus and/or if collateral veins have already formed, and

- that the chance for the technical success of portosystemic shunt creation (specifically, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts (TIPS) discussed below) is less likely if there is thrombus obscuring the portal vein and making the anatomy more difficult to navigate.

Different physicians define "chronic" in different ways. Two common definitions of "chronic" are:

- Thrombus proven to have been present for at least 4 weeks based on imaging or based on a reliable history of when symptoms started and

- Thrombus associated with visible collateral veins on imaging.

Some institutions do not offer TIPS to patients with chronic PVT, and some do[6]. Some institutions also do not offer TIPS for mild PVT (e.g. such as PVT estimated to occlude <25% of the main PV lumen).

Evaluation

When portal vein obstruction is suspected, several modalities can help confirm or exclude the diagnosis. The first line of investigation is Doppler ultrasound. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound seems to be superior to Doppler ultrasound for the characterization and further evaluation of portal vein obstruction.[7]

Liver function tests are expected to be normal unless there is underlying liver disease. Other recommended blood tests should encompass extensive procoagulant factors workup, including antiphospholipid syndrome, protein C, S, antithrombin III levels, factor V, and Leiden mutation.

Risk of death from TIPS formation increases in a near exponential fashion as Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) and Child-Pugh scores increase, with most radiologists/institutions having upper limit values above which they will not offer portosystemic shunt procedures as the potential risks likely outweigh the benefits. The institutions that do offer TIPS often have an upper limit Child-Pugh or MELD score above which they will not attempt it[6].

CT and MRI provide additional information such as the extension of thrombus, evidence of bowel infarction, and the status of adjacent organs. The sensitivity and specificity for MRI in detecting a primary portal vein thrombosis are 100% and 98%, respectively. MRI is valuable in determining the resectability of neoplasm involving the portal venous system and follow-up after therapeutic procedures.[8]

Endoscopy is essential in patients with overt upper gastrointestinal bleeding and can be helpful in patients presenting with symptoms of gastritis. Esophageal varices are a common finding in patients with chronic portal vein obstruction. If identified early, esophageal varices can be cauterized or clipped to prevent potentially life-threatening hemorrhage.

Treatment / Management

Treatment of thrombosis in cirrhosis patients can present a significant challenge as balancing anticoagulation with the risk of bleeding can be problematic. The Anticoagulation Forum recommends that cirrhotic patients with portal vein thrombosis should undergo endoscopic screening of esophageal varices and, if indicated, banding treatment should precede low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) treatment.[9]

Choosing the right anticoagulant for a patient is difficult as well, as each agent has its benefits and risks. As cirrhotic patients have a raised international normalized ratio (INR) at baseline, monitoring warfarin treatment can be challenging. Despite some disadvantages, LMWH and vitamin K antagonists have been successfully used to treat thrombosis in cirrhotic patients. According to the guidelines of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, acute portal vein thrombosis should be treated for at least 3 months with LMWH and switched to oral anticoagulant agents after patient stabilization. One study demonstrated partial or complete recanalization rates of up to 60% in cirrhotic patients treated early with LMWH or vitamin K antagonists.[10]

The use of vitamin K antagonists has been the object of study, but no target INR has been defined. The study quoted above used a target INR of 2.5 for the patients using warfarin. However, no data yet suggests what the goal INR should be for PVT patients treated with warfarin. With LMWH being well-studied and not requiring monitoring, it might be the best option for some.[11]

Despite recanalization, the possibility of recurrent DVT remains. One trial noted a recurrence rate of 38% after complete recanalization while another showed 27%.[10][11]

Despite the interest in direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs), there is insufficient data to recommend their use. There have been some in vitro and theoretical literature supporting their use, but studies establishing their safety and efficacy are lacking at the moment.

PVT is so extensive that it obscures targets/landmarks making an attempt at TIPS insertion likely to fail should, when possible, be treated with anticoagulation first.

For obstruction caused by local invasion, treatment of the underlying malignancy might be helpful. In patients with an obstruction due to pancreatic cancer, chemotherapy has led to recanalization and improvement in survival.[12]

Non-Surgical Procedures

IR can offer several techniques for treating some forms of portal vein thrombosis. However, treatment algorithms for the role of IR in PVT have not been specifically addressed in any consensus publication, including the most recent practice guidelines of

- the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease for non-tumor thrombosis[13]

- the National Cancer Comprehensive Network for tumor thrombus by invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma or

- the Society of Interventional Radiology[14] (B2)

Also, none of these techniques have been proven to be superior to medical therapy for particular patient populations by any prospective studies.

When a patient with PVT has no clinical or anatomic sequelae of portal vein hypertension and has a strong contraindication to anticoagulation, then transhepatic thrombectomy can be attempted. In this procedure, the IR typically accesses the portal vein via puncture through the abdominal wall into the liver and then attempts to break down the thrombus mechanically. However, this is an off-label (non-Food and Drug Administration-approved) technique for the instruments that the procedure requires. Alternatively, if the patient has no strong contraindication to anticoagulation and has known acute PVT that for some reason is considered to have failed oral anticoagulation or is likely to take too long to respond to oral anticoagulation, then intra-arterial thrombolysis with a catheter placed in the superior mesenteric artery can be attempted[15]. This latter technique requires only a single peripheral arterial puncture.(B3)

Particularly when there are sequelae of portal vein hypertension, creation of a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) becomes a potentially best option to treat both the PVT and other sequelae of portal vein hypertension simultaneously. TIPS can reduce or cure the symptoms of PVT.

Direct thrombolysis via the transhepatic route is an option if one wants to avoid systemic therapy. TPA has been used in some cases with success.

A transvenous intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) is considered a highly effective and relatively safe treatment modality. In a recent study of 70 cirrhosis patients who received TIPS, partial and complete recanalization was found in 57% and 30% respectively.[16](B2)

TIPS has been shown to reduce the risk of internal bleeding over 2 years in persons with PVT[17] compared to alternatives such as esophageal varix banding and propranolol. (A1)

However, TIPS has not been shown to prolong survival in this particular population (patients with PVT, either benign or malignant). Furthermore, TIPS is associated with considerable risks, e.g. life-altering complications that may make the risks outweigh the benefits[14], such as (B2)

- procedure-related death,

- hepatic encephalopathy, and even in the absence of these,

- the need for life-long stent follow-up imaging exams with fair chance of the need for a repeat procedure/reintervention if the TIPS occludes.

In one study of patients with PVT who underwent TIPS, the rate of encephalopathy at 12 and 24 months was 27% and 32%, respectively[6]. The rate of TIPS dysfunction at 24 months was 29%. Further details about the risks of TIPS are beyond the scope of this article.(B3)

A randomized controlled trial showed that patients who did not have extensive PVT prior to successful TIPS insertion and whose PVT was related to cirrhosis "did not benefit from anticoagulation therapy (after TIPS) with respect to portal vein recanalization or clinical outcomes during the 12-month follow-up period[18]."

Overall, TIPS is associated with worse outcomes in liver transplant recipients. It is associated with increased post-transplant morbidity, graft loss, and mortality.[19][20](B2)

Surgical Procedures

Other surgical modalities used in the treatment of portal vein occlusion associated with variceal bleeding include shunt surgery (such as splenorenal and mesogonadal) and the controversial Sugiura procedure. However, the Sugiura procedure is rarely an option.[21] Similar to TIPS, because of the associated risks, surgery for PVT should only be used as a salvage therapy, such as when anticoagulation is strongly contraindicated or has clearly failed and there are no strong contraindications to the invasive procedure or when patients are willing to accept the potentially significant serious outcomes and there are no or minor contraindications to the invasive procedure.

The role of shunt surgery is debatable and most experts recommend endoscopic treatment and propranolol in patients with recurrent bleeding. If shunt surgery is undertaken, a distal splenorenal shunt is recommended. If the splenic vein is thrombosed, splenectomy at the time of shunt surgery is an option. If patients have cirrhosis, the mortality of shunt surgery is extremely high.

One should keep in mind the possibility of liver nodules forming in patients undergoing shunt procedures. Such nodules are known to present in patients with congenital portosystemic shunts without liver disease.[22](B2)

Liver transplant is an option for less than 5% of patients. five-year survival rates of 60% have been reported but surgery is also associated with numerous complications.

Differential Diagnosis

Since portal vein obstruction is more of a radiological than clinical diagnosis, it is less likely to be suspected in a patient without ample evidence. However, due to similar symptomatology or pathophysiology, the following differentials should be ruled out:

- Primary biliary cirrhosis

- Arsenic toxicity

- Budd-Chiari syndrome

- Cirrhosis

- Sarcoidosis

- Schistosomiasis

Prognosis

The overall prognosis is excellent, with 10-year mortality of 25% and an overall mortality rate of approximately 10%. In the presence of cirrhosis and malignancy, the prognosis is worse and is dependent upon the underlying condition. However, other complications include esophageal varices which carry a high mortality. children tend to have a better prognosis as the cause is rarely a cancer or end-stage liver disease.

Complications

Complications of portal vein occlusion include:

Portal Hypertension

This can present in multiple forms, including ascites, variceal hemorrhage, or hypersplenism.

Mesenteric Infarction

Usually seen in acute portal vein thrombosis, leading to blockage of blood flow from the mesenteries.

Worsening Hepatic Function

In patients with cirrhosis, portal vein obstruction can lead to worsening liver function.

Acute Pylephlebitis

Septic portal vein thrombosis can occur if there is a concurrent abdominal focus of infection (appendicitis, diverticulitis, etc.)

Deterrence and Patient Education

Villa et al., performed a randomized controlled trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of enoxaparin in preventing portal vein thrombosis (PVT) in patients with advanced cirrhosis. They found that "In a small randomized controlled trial, a 12-month course of enoxaparin was safe and effective in preventing PVT in patients with cirrhosis and a Child-Pugh score of 7-10. Enoxaparin appeared to delay the occurrence of hepatic decompensation and to improve survival."[23] However, these findings require replication in more substantial, multi-centered trials.

Patients who are at high risk for portal vein thrombosis should be educated about these possible complications and be told to report new symptoms which could lead to an early diagnosis.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Portal vein obstruction, especially in the form of thrombosis, is a relatively common problem (especially in patients with liver disease). The disorder if left untreated is ultimately fatal, thus because of the diverse causes and treatments, the condition is best managed by an interprofessional team. Pediatricians who encounter children with portal vein thrombosis should immediately refer them to a tertiary care center. High-risk patients should receive streamlined care for early diagnosis and treatment. Early treatment with anticoagulation or TIPS might lead to survival benefit for the patient.[16]

Both the nurse and pharmacist, along with physicians, should educate the patient on the importance of compliance with the anticoagulants and thrombolytics as part of an interprofessional team approach to portal vein obstruction. These patients also need to return to the clinic to ensure that the INR is in the therapeutic range. Some patients with recurrent bleeding may be managed with propranolol and thus compliance with treatment is necessary to prevent the high morbidity. Patients with end-stage liver disease should be seen by a transplant nurse to determine their eligibility for a liver transplant. All these examples of interprofessional coordination will guide outcomes optimally. [Level 5]

For patients with advanced malignancy, palliative care and a pain management team must be involved early in the care. The aim is to ensure that the quality of life is not worsened.

Media

References

Mantaka A, Augoustaki A, Kouroumalis EA, Samonakis DN. Portal vein thrombosis in cirrhosis: diagnosis, natural history, and therapeutic challenges. Annals of gastroenterology. 2018 May-Jun:31(3):315-329. doi: 10.20524/aog.2018.0245. Epub 2018 Mar 3 [PubMed PMID: 29720857]

Okuda K, Ohnishi K, Kimura K, Matsutani S, Sumida M, Goto N, Musha H, Takashi M, Suzuki N, Shinagawa T. Incidence of portal vein thrombosis in liver cirrhosis. An angiographic study in 708 patients. Gastroenterology. 1985 Aug:89(2):279-86 [PubMed PMID: 4007419]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNonami T, Yokoyama I, Iwatsuki S, Starzl TE. The incidence of portal vein thrombosis at liver transplantation. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.). 1992 Nov:16(5):1195-8 [PubMed PMID: 1427658]

Delahousse B,Labat-Debelleix V,Decalonne L,d'Alteroche L,Perarnau JM,Gruel Y, Comparative study of coagulation and thrombin generation in the portal and jugular plasma of patients with cirrhosis. Thrombosis and haemostasis. 2010 Oct; [PubMed PMID: 20806106]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePlessier A, Darwish-Murad S, Hernandez-Guerra M, Consigny Y, Fabris F, Trebicka J, Heller J, Morard I, Lasser L, Langlet P, Denninger MH, Vidaud D, Condat B, Hadengue A, Primignani M, Garcia-Pagan JC, Janssen HL, Valla D, European Network for Vascular Disorders of the Liver (EN-Vie). Acute portal vein thrombosis unrelated to cirrhosis: a prospective multicenter follow-up study. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.). 2010 Jan:51(1):210-8. doi: 10.1002/hep.23259. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19821530]

Miraglia R, Maruzzelli L, Luca A. Transjugular intrahepatic porto-systemic shunt placement in a patient with left-lateral split-liver transplant and mesenterico-left portal vein by pass placement. Cardiovascular and interventional radiology. 2011 Dec:34(6):1316-9. doi: 10.1007/s00270-011-0199-6. Epub 2011 Jun 7 [PubMed PMID: 21647805]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDanila M, Sporea I, Popescu A, Șirli R. Portal vein thrombosis in liver cirrhosis - the added value of contrast enhanced ultrasonography. Medical ultrasonography. 2016 Jun:18(2):218-33. doi: 10.11152/mu.2013.2066.182.pvt. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27239658]

Lin J,Zhou KR,Chen ZW,Wang JH,Wu ZQ,Fan J, Three-dimensional contrast-enhanced MR angiography in diagnosis of portal vein involvement by hepatic tumors. World journal of gastroenterology. 2003 May; [PubMed PMID: 12717869]

Ageno W, Beyer-Westendorf J, Garcia DA, Lazo-Langner A, McBane RD, Paciaroni M. Guidance for the management of venous thrombosis in unusual sites. Journal of thrombosis and thrombolysis. 2016 Jan:41(1):129-43. doi: 10.1007/s11239-015-1308-1. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26780742]

Delgado MG, Seijo S, Yepes I, Achécar L, Catalina MV, García-Criado A, Abraldes JG, de la Peña J, Bañares R, Albillos A, Bosch J, García-Pagán JC. Efficacy and safety of anticoagulation on patients with cirrhosis and portal vein thrombosis. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2012 Jul:10(7):776-83. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.01.012. Epub 2012 Jan 28 [PubMed PMID: 22289875]

Amitrano L, Guardascione MA, Menchise A, Martino R, Scaglione M, Giovine S, Romano L, Balzano A. Safety and efficacy of anticoagulation therapy with low molecular weight heparin for portal vein thrombosis in patients with liver cirrhosis. Journal of clinical gastroenterology. 2010 Jul:44(6):448-51. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181b3ab44. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19730112]

Jaseanchiun W,Kato H,Hayasaki A,Fujii T,Iizawa Y,Tanemura A,Murata Y,Azumi Y,Kuriyama N,Kishiwada M,Mizuno S,Usui M,Sakurai H,Isaji S, The clinical impact of portal venous patency ratio on prognosis of patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma undergoing pancreatectomy with combined resection of portal vein following preoperative chemoradiotherapy. Pancreatology : official journal of the International Association of Pancreatology (IAP) ... [et al.]. 2019 Jan 25; [PubMed PMID: 30738764]

DeLeve LD, Valla DC, Garcia-Tsao G, American Association for the Study Liver Diseases. Vascular disorders of the liver. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.). 2009 May:49(5):1729-64. doi: 10.1002/hep.22772. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19399912]

Dariushnia SR, Haskal ZJ, Midia M, Martin LG, Walker TG, Kalva SP, Clark TW, Ganguli S, Krishnamurthy V, Saiter CK, Nikolic B, Society of Interventional Radiology Standards of Practice Committee. Quality Improvement Guidelines for Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunts. Journal of vascular and interventional radiology : JVIR. 2016 Jan:27(1):1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2015.09.018. Epub 2015 Nov 21 [PubMed PMID: 26614596]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceJiang JF, Lao YC, Yuan BH, Yin J, Liu X, Chen L, Zhong JH. Treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombus: advances and challenges. Oncotarget. 2017 May 16:8(20):33911-33921. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15411. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28430610]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLuca A,Miraglia R,Caruso S,Milazzo M,Sapere C,Maruzzelli L,Vizzini G,Tuzzolino F,Gridelli B,Bosch J, Short- and long-term effects of the transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt on portal vein thrombosis in patients with cirrhosis. Gut. 2011 Jun; [PubMed PMID: 21357252]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLuo X, Wang Z, Tsauo J, Zhou B, Zhang H, Li X. Advanced Cirrhosis Combined with Portal Vein Thrombosis: A Randomized Trial of TIPS versus Endoscopic Band Ligation Plus Propranolol for the Prevention of Recurrent Esophageal Variceal Bleeding. Radiology. 2015 Jul:276(1):286-93. doi: 10.1148/radiol.15141252. Epub 2015 Mar 10 [PubMed PMID: 25759969]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWang MY, Wang MH, Peng Y, You HB, Chen XF, Zhao L, Gan L, Li M, Li JZ, Gong JP, Li XH. Cannulation Selection of Portal Venous and Splenic Venous Catheterization in Venovenous Bypass of Swine Orthotopic Liver Transplantation. Annals of transplantation. 2016 Jun 2:21():346-9 [PubMed PMID: 27251849]

Englesbe MJ, Schaubel DE, Cai S, Guidinger MK, Merion RM. Portal vein thrombosis and liver transplant survival benefit. Liver transplantation : official publication of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the International Liver Transplantation Society. 2010 Aug:16(8):999-1005. doi: 10.1002/lt.22105. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20677291]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDoenecke A,Tsui TY,Zuelke C,Scherer MN,Schnitzbauer AA,Schlitt HJ,Obed A, Pre-existent portal vein thrombosis in liver transplantation: influence of pre-operative disease severity. Clinical transplantation. 2010 Jan-Feb; [PubMed PMID: 19236435]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSelzner M, Tuttle-Newhall JE, Dahm F, Suhocki P, Clavien PA. Current indication of a modified Sugiura procedure in the management of variceal bleeding. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2001 Aug:193(2):166-73 [PubMed PMID: 11491447]

Pupulim LF, Vullierme MP, Paradis V, Valla D, Terraz S, Vilgrain V. Congenital portosystemic shunts associated with liver tumours. Clinical radiology. 2013 Jul:68(7):e362-9. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2013.01.024. Epub 2013 Mar 26 [PubMed PMID: 23537576]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceVilla E, Cammà C, Marietta M, Luongo M, Critelli R, Colopi S, Tata C, Zecchini R, Gitto S, Petta S, Lei B, Bernabucci V, Vukotic R, De Maria N, Schepis F, Karampatou A, Caporali C, Simoni L, Del Buono M, Zambotto B, Turola E, Fornaciari G, Schianchi S, Ferrari A, Valla D. Enoxaparin prevents portal vein thrombosis and liver decompensation in patients with advanced cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2012 Nov:143(5):1253-1260.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.07.018. Epub 2012 Jul 20 [PubMed PMID: 22819864]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence