Introduction

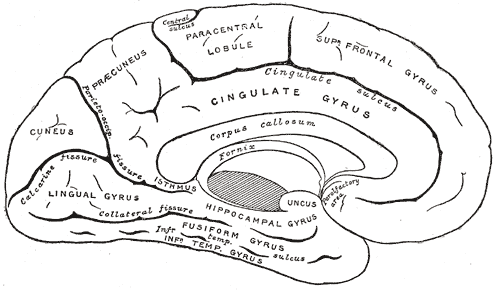

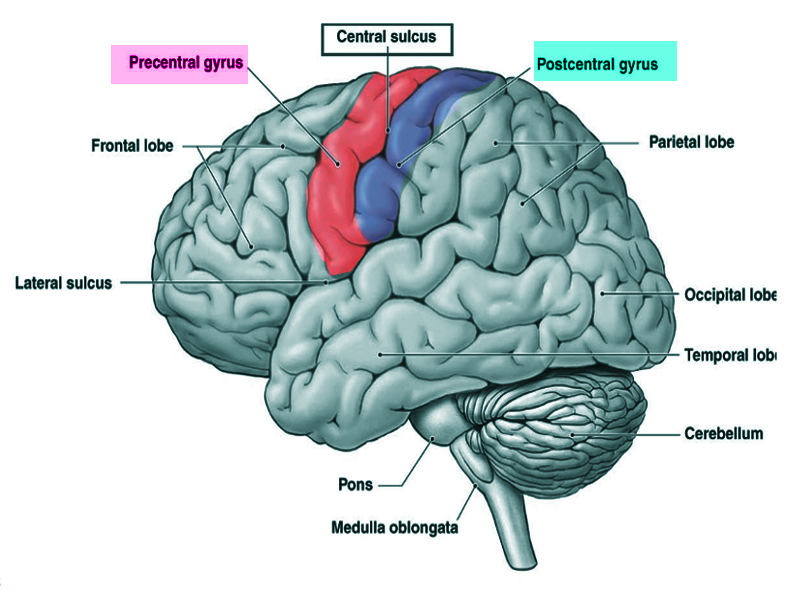

The postcentral gyrus is on the lateral surface of the parietal lobes between the central sulcus and postcentral sulcus. The postcentral gyrus contains the primary somatosensory cortex, a significant brain region responsible for proprioception.[1] This region perceives various somatic sensations from the body, including touch, pressure, temperature, and pain.[2] After stimulation, these peripheral somatosensory receptors relay through the dorsal spinal cord and terminate in the postcentral gyrus where the stimuli are perceived.[3]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The postcentral gyrus is found on the lateral surface of the anterior parietal lobe, caudal to the central sulcus, and corresponds to Brodmann areas 3b, 1, and 2.[4] The primary somatosensory cortex perceives sensations on the contralateral side. The topographic organization of this region is known as the sensory homunculus, or “little man.” This organization of the somatosensory map is such that the medial aspect is responsible for lower extremity sensation, the dorsolateral aspect is responsible for the upper extremity, and the most lateral aspect is responsible for the face, lips, and tongue.[5] However, regions of the homunculus that require high sensory acuity and resolution take up a larger area on the somatosensory map. For example, the hands, face, and lips necessitate fine somatosensory perception relative to other regions, such as the leg or torso.[5][6] The postcentral gyrus also houses the secondary somatosensory cortex, which appears to play a role in the integration of somatosensory stimuli and memory formation.[7]

Embryology

The early central nervous system first appears as the neural tube. Over time, the anterior portion of the neural tube develops into the forebrain, midbrain, and hindbrain, and the dorsal neural tube differentiates to become the somatosensory pathway in the brain and spinal cord.[8] In the forebrain, a variety of factor gradients, including SHH, WNT, and BMP, gives rise to the telencephalon.[9] By the end of the fifth month of development, the central sulcus has formed separating the precentral and postcentral gyri.[10] Between the late third trimester and birth, the primary somatosensory cortex spatially differentiates forming the topographic sensory map.[11]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The anterior and middle cerebral arteries provide the postcentral gyrus blood supply. The anterior cerebral artery is responsible for perfusing the medial third of the postcentral gyrus, while the middle cerebral artery perfuses the lateral two-thirds of the postcentral gyrus. Venous blood drains through the superior sagittal sinus for the superior two-thirds of the postcentral gyrus and the superficial Sylvian veins to the transverse sinus for the inferior third of the postcentral gyrus.[12]

Nerves

Dorsal Column-Medial Lemniscus Pathway

The dorsal column-medial lemniscus pathway is the primary somatosensory pathway for fine touch, vibration, two-point discrimination, and proprioception. This pathway is comprised of three neurons that connect the mechanoreceptor to its specific region within the primary somatosensory cortex. Meissner's corpuscles, Merkel's disks, and Ruffini's corpuscles are stimulated by touch, vibration, and skin tension, respectively leading to the production of an action potential in the first-order neuron.[13] These first-order neurons are pseudounipolar with their cell bodies found in the dorsal root ganglion.[14] Axons below the T6 level travel up the medial dorsal column as the fasciculus gracilis, while axons above the T6 level travel up the lateral dorsal column as the fasciculus cuneatus.[15][16] These columns synapse with the second-order neurons in the nucleus gracilis and nucleus cuneatus in the medulla. The second-order neurons crossover to the contralateral side and ascend, forming the medial lemniscus. Like the dorsal columns, the medial lemniscus is also spatially organized. However, rather than being structured in a medial to the lateral direction, the lower extremity axons are found more ventrally, and the upper extremity axons more dorsal. The medial lemniscus continues into the midbrain and synapses in the ventral posterior nucleus of the thalamus.[14] Again, these synapses topographically organize with the ventral posterolateral nucleus responsible for somatosensation of the body and the ventral posteromedial nucleus responsible for somatosensation of the head.[17] Finally, the third-order neurons ascend through the posterior internal capsule to the specific region within the primary somatosensory cortex.[14]

Spinothalamic Tract

The spinothalamic tract (also known as the ventrolateral system) is the somatosensory pathway for crude touch, pressure, nociception, and temperature. The spinothalamic tract divides into two systems; the anterior spinothalamic system is responsible for crude touch and pressure, and the lateral spinothalamic system is responsible for pain and temperature sensation.

In the anterior spinothalamic system, A-beta fibers carrying crude touch and pressure stimuli travel through the dorsal root ganglion and synapse in the ipsilateral dorsal horn. A-beta fibers are myelinated and have a large diameter compared to other fiber types in the spinothalamic tract.[18] The second-order neuron passes through the anterior white commissure of the spinal cord and ascends as the anterior spinothalamic tract on the contralateral side. Axons from the body synapse in the ventral posterolateral thalamus and third-order neurons travel through the posterior limb of the internal capsule and terminate in their appropriate region within the postcentral gyrus.

Unlike the anterior spinothalamic system, the lateral spinothalamic system is made up of multiple nerve fiber types. A-delta fibers are myelinated nerves with a smaller diameter than A-beta fibers.[18] Type I A-delta fibers respond to mechanical and chemical stimuli but have a high threshold of activation for heat stimuli, whereas type II A-delta fibers are sensitive to heat and have a high mechanical threshold.[18] Together, A-delta fiber afferents signal for the "first" pain response, a rapid nociceptive stimulation that triggers a reflex arc to remove the body from the painful stimulus.[19] C-fibers are unmyelinated, small diameter nociceptive nerves that can respond to mechanical and temperature stimuli.[18] C-fibers are slowly conducting neurons responsible for the "second" pain, the burning, or aching pain associated with an injury.[19] Like the anterior spinothalamic system, the lateral spinothalamic system synapses in the dorsal horn and crosses to the contralateral side at the same level of the spinal cord; however, these fibers ascend as the lateral spinothalamic tract. Again, these fibers will synapse in the ventral posterolateral nucleus of the thalamus, travel through the corona radiata, and synapse in the correct topographic region within the primary somatosensory cortex.[18][19]

Physiologic Variants

Although there are interhemispheric and interindividual variations in the gross appearance of postcentral gyri, the overall topographic sensory distribution remains the same.[20] However, postcentral gyrus grey matter volume has shown to correlate positively with improved somatosensory processing.[21]

Surgical Considerations

Common surgical considerations regarding the postcentral gyrus or structures near the postcentral gyrus, such as the precentral gyrus, posterior parietal lobe, or insula, include tumor resection surgery, brain mapping for treatment of seizures, and treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. Cancers that can manifest near the postcentral gyrus include gliomas, astrocytomas, oligodendrogliomas, and meningiomas. Patients with lesions in the primary somatosensory cortex experience somatosensory deficits, especially in the hands and face.[22] Uncontrolled growth of these tumors near or within the postcentral gyrus makes surgical resection difficult to perform without any post-operative somatosensory loss. However, new developments in cerebral tumor resection techniques have shown improvements in glioma and meningioma microsurgery resections near the postcentral gyrus.[23][24][25] Another improvement in tumor resection surgeries has been preoperative transcortical magnetic stimulation in conjunction with fMRI. This method has shown to improve resection margins in precentral glioma resections and preserve motor functions.[26][27] Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulations have shown to improve tactile discrimination and reorganize the somatosensory map.[28][29]

Other surgical considerations involving the postcentral gyrus are the use of deep brain stimulation for the treatment of Parkinson disease. Patients with Parkinson disease undergo deep brain stimulation and dopaminergic therapy to correct motor deficits. The subthalamic nucleus and globus pallidus internus are two common targets for deep brain stimulation to treat motor symptoms seen in Parkinson disease.[30] Unfortunately, these therapies can negatively impact somatosensation and the primary somatosensory cortex. Positron emission tomography and magnetoencephalography reveal deep brain stimulation can result in deleterious effects on somatosensation while effectively treating Parkinson disease-related motor symptoms.[31][32] It is important to monitor patients undergoing deep brain stimulation to ensure they are not experiencing any lasting sensory deficits.

Clinical Significance

Stroke

The postcentral gyrus is at risk of damage due to strokes. The two major arteries that supply the postcentral gyrus are the anterior and middle cerebral arteries. Sensory deficits can often help to determine which artery is affected and the location of the infarct. For example, ischemic stroke in the anterior cerebral artery will affect the medial postcentral gyrus and may present with sensory deficits in the contralateral leg. A stroke in the middle cerebral artery may show a contralateral sensory loss in the face or upper extremity, depending on the location of the infarct. Cerebral infarctions to these arteries will often have accompanying motor deficits, aphasia, and visual deficits depending on the location of the occlusion.

Pain Modulation

Nociception pathways can be suppressed by ascending and descending modulating pathways. The pain perception circuit in the brain includes the primary somatosensory cortex, insula, anterior cingulate gyrus, prefrontal cortex, and thalamus.[33] These regions are important for the perception of the painful stimulus and play a role in learning and memory to prevent the painful stimulus from occurring in the future. Although this system is essential for responding to acute pain, dysregulation of the nociceptive pathway can lead to chronic pathologic pain. Descending pain modulating pathways function to prevent chronic pain, which may manifest as overactive and hypersensitive nociception.

Descending pain modulating pathways appear to originate in the periaqueductal grey and rostroventral medial medulla.[34] Activation of the descending pain modulating pathway leads to the activation of inhibitory interneurons in the spinal cord and subsequent release of endogenous opioids and acetylcholine.[35][36] Opioid ligands bind to the presynaptic receptors hyperpolarizing the neuron and preventing the release of substance P, thus stopping the transmission of the painful stimulus while leaving non-nociceptive sensation intact.[35] This pathway is also the target for exogenous opioid pharmacotherapy for the treatment of pain. However, presynaptic opioid receptors become tolerant with continuous drug therapy; prolonged opioid administration leads to the downregulation of the opioid receptors at the presynaptic neuronal surface. Therefore, patients should not receive treatment with opiates for chronic pain.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Kropf E, Syan SK, Minuzzi L, Frey BN. From anatomy to function: the role of the somatosensory cortex in emotional regulation. Revista brasileira de psiquiatria (Sao Paulo, Brazil : 1999). 2019 May-Jun:41(3):261-269. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2018-0183. Epub 2018 Dec 6 [PubMed PMID: 30540029]

Lloyd DM, McGlone FP, Yosipovitch G. Somatosensory pleasure circuit: from skin to brain and back. Experimental dermatology. 2015 May:24(5):321-4. doi: 10.1111/exd.12639. Epub 2015 Mar 9 [PubMed PMID: 25607755]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLai HC, Seal RP, Johnson JE. Making sense out of spinal cord somatosensory development. Development (Cambridge, England). 2016 Oct 1:143(19):3434-3448 [PubMed PMID: 27702783]

Akselrod M, Martuzzi R, Serino A, van der Zwaag W, Gassert R, Blanke O. Anatomical and functional properties of the foot and leg representation in areas 3b, 1 and 2 of primary somatosensory cortex in humans: A 7T fMRI study. NeuroImage. 2017 Oct 1:159():473-487. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.06.021. Epub 2017 Jun 17 [PubMed PMID: 28629975]

Schott GD. Penfield's homunculus: a note on cerebral cartography. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 1993 Apr:56(4):329-33 [PubMed PMID: 8482950]

Roux FE, Djidjeli I, Durand JB. Functional architecture of the somatosensory homunculus detected by electrostimulation. The Journal of physiology. 2018 Mar 1:596(5):941-956. doi: 10.1113/JP275243. Epub 2018 Jan 19 [PubMed PMID: 29285773]

Chen TL, Babiloni C, Ferretti A, Perrucci MG, Romani GL, Rossini PM, Tartaro A, Del Gratta C. Human secondary somatosensory cortex is involved in the processing of somatosensory rare stimuli: an fMRI study. NeuroImage. 2008 May 1:40(4):1765-71. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.01.020. Epub 2008 Jan 29 [PubMed PMID: 18329293]

Darnell D, Gilbert SF. Neuroembryology. Wiley interdisciplinary reviews. Developmental biology. 2017 Jan:6(1):. doi: 10.1002/wdev.215. Epub 2016 Dec 1 [PubMed PMID: 27906497]

Agirman G, Broix L, Nguyen L. Cerebral cortex development: an outside-in perspective. FEBS letters. 2017 Dec:591(24):3978-3992. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.12924. Epub 2017 Dec 14 [PubMed PMID: 29194577]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRibas GC. The cerebral sulci and gyri. Neurosurgical focus. 2010 Feb:28(2):E2. doi: 10.3171/2009.11.FOCUS09245. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20121437]

Dall'Orso S, Steinweg J, Allievi AG, Edwards AD, Burdet E, Arichi T. Somatotopic Mapping of the Developing Sensorimotor Cortex in the Preterm Human Brain. Cerebral cortex (New York, N.Y. : 1991). 2018 Jul 1:28(7):2507-2515. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhy050. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29901788]

Frigeri T, Paglioli E, de Oliveira E, Rhoton AL Jr. Microsurgical anatomy of the central lobe. Journal of neurosurgery. 2015 Mar:122(3):483-98. doi: 10.3171/2014.11.JNS14315. Epub 2015 Jan 2 [PubMed PMID: 25555079]

Zimmerman A, Bai L, Ginty DD. The gentle touch receptors of mammalian skin. Science (New York, N.Y.). 2014 Nov 21:346(6212):950-4. doi: 10.1126/science.1254229. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25414303]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMacDonald DB, Dong C, Quatrale R, Sala F, Skinner S, Soto F, Szelényi A. Recommendations of the International Society of Intraoperative Neurophysiology for intraoperative somatosensory evoked potentials. Clinical neurophysiology : official journal of the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology. 2019 Jan:130(1):161-179. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2018.10.008. Epub 2018 Nov 14 [PubMed PMID: 30470625]

Hagiwara Y, Goto J, Goto N, Ezure H, Moriyama H. Age-related changes in nerve fibers of the human fasciculus gracilis. Okajimas folia anatomica Japonica. 2003 May:80(1):1-5 [PubMed PMID: 12858959]

Pearce JM. Burdach's column. European neurology. 2006:55(3):179-80 [PubMed PMID: 16733361]

Behrens TE, Johansen-Berg H, Woolrich MW, Smith SM, Wheeler-Kingshott CA, Boulby PA, Barker GJ, Sillery EL, Sheehan K, Ciccarelli O, Thompson AJ, Brady JM, Matthews PM. Non-invasive mapping of connections between human thalamus and cortex using diffusion imaging. Nature neuroscience. 2003 Jul:6(7):750-7 [PubMed PMID: 12808459]

Basbaum AI, Bautista DM, Scherrer G, Julius D. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of pain. Cell. 2009 Oct 16:139(2):267-84. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.028. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19837031]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceEckert NR, Vierck CJ, Simon CB, Cruz-Almeida Y, Fillingim RB, Riley JL 3rd. Testing Assumptions in Human Pain Models: Psychophysical Differences Between First and Second Pain. The journal of pain. 2017 Mar:18(3):266-273. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2016.10.019. Epub 2016 Nov 22 [PubMed PMID: 27888117]

White LE, Andrews TJ, Hulette C, Richards A, Groelle M, Paydarfar J, Purves D. Structure of the human sensorimotor system. I: Morphology and cytoarchitecture of the central sulcus. Cerebral cortex (New York, N.Y. : 1991). 1997 Jan-Feb:7(1):18-30 [PubMed PMID: 9023429]

Yoshimura S, Sato W, Kochiyama T, Uono S, Sawada R, Kubota Y, Toichi M. Gray matter volumes of early sensory regions are associated with individual differences in sensory processing. Human brain mapping. 2017 Dec:38(12):6206-6217. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23822. Epub 2017 Sep 20 [PubMed PMID: 28940867]

Taylor L, Jones L. Effects of lesions invading the postcentral gyrus on somatosensory thresholds on the face. Neuropsychologia. 1997 Jul:35(7):953-61 [PubMed PMID: 9226657]

Deng WS, Zhou XY, Li ZJ, Xie HW, Fan MC, Sun P. Microsurgical treatment for central gyrus region meningioma with epilepsy as primary symptom. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2014 Sep:25(5):1773-5. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000000889. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24999673]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRey-Dios R, Cohen-Gadol AA. Technical nuances for surgery of insular gliomas: lessons learned. Neurosurgical focus. 2013 Feb:34(2):E6. doi: 10.3171/2012.12.FOCUS12342. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23373451]

De Witt Hamer PC, Robles SG, Zwinderman AH, Duffau H, Berger MS. Impact of intraoperative stimulation brain mapping on glioma surgery outcome: a meta-analysis. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2012 Jul 10:30(20):2559-65. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.4818. Epub 2012 Apr 23 [PubMed PMID: 22529254]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFrey D, Schilt S, Strack V, Zdunczyk A, Rösler J, Niraula B, Vajkoczy P, Picht T. Navigated transcranial magnetic stimulation improves the treatment outcome in patients with brain tumors in motor eloquent locations. Neuro-oncology. 2014 Oct:16(10):1365-72. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nou110. Epub 2014 Jun 12 [PubMed PMID: 24923875]

Magill ST, Han SJ, Li J, Berger MS. Resection of primary motor cortex tumors: feasibility and surgical outcomes. Journal of neurosurgery. 2018 Oct:129(4):961-972. doi: 10.3171/2017.5.JNS163045. Epub 2017 Dec 8 [PubMed PMID: 29219753]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTegenthoff M, Ragert P, Pleger B, Schwenkreis P, Förster AF, Nicolas V, Dinse HR. Improvement of tactile discrimination performance and enlargement of cortical somatosensory maps after 5 Hz rTMS. PLoS biology. 2005 Nov:3(11):e362 [PubMed PMID: 16218766]

Pleger B, Blankenburg F, Bestmann S, Ruff CC, Wiech K, Stephan KE, Friston KJ, Dolan RJ. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation-induced changes in sensorimotor coupling parallel improvements of somatosensation in humans. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2006 Feb 15:26(7):1945-52 [PubMed PMID: 16481426]

Almeida L, Deeb W, Spears C, Opri E, Molina R, Martinez-Ramirez D, Gunduz A, Hess CW, Okun MS. Current Practice and the Future of Deep Brain Stimulation Therapy in Parkinson's Disease. Seminars in neurology. 2017 Apr:37(2):205-214. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1601893. Epub 2017 May 16 [PubMed PMID: 28511261]

Bradberry TJ, Metman LV, Contreras-Vidal JL, van den Munckhof P, Hosey LA, Thompson JL, Schulz GM, Lenz F, Pahwa R, Lyons KE, Braun AR. Common and unique responses to dopamine agonist therapy and deep brain stimulation in Parkinson's disease: an H(2)(15)O PET study. Brain stimulation. 2012 Oct:5(4):605-15. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2011.09.002. Epub 2011 Oct 5 [PubMed PMID: 22019080]

Sridharan KS, Højlund A, Johnsen EL, Sunde NA, Johansen LG, Beniczky S, Østergaard K. Differentiated effects of deep brain stimulation and medication on somatosensory processing in Parkinson's disease. Clinical neurophysiology : official journal of the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology. 2017 Jul:128(7):1327-1336. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2017.04.014. Epub 2017 May 2 [PubMed PMID: 28570866]

Apkarian AV, Bushnell MC, Treede RD, Zubieta JK. Human brain mechanisms of pain perception and regulation in health and disease. European journal of pain (London, England). 2005 Aug:9(4):463-84 [PubMed PMID: 15979027]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceZhuo M. Descending facilitation. Molecular pain. 2017 Jan:13():1744806917699212. doi: 10.1177/1744806917699212. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28326945]

Corder G, Castro DC, Bruchas MR, Scherrer G. Endogenous and Exogenous Opioids in Pain. Annual review of neuroscience. 2018 Jul 8:41():453-473. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-080317-061522. Epub 2018 May 31 [PubMed PMID: 29852083]

Naser PV, Kuner R. Molecular, Cellular and Circuit Basis of Cholinergic Modulation of Pain. Neuroscience. 2018 Sep 1:387():135-148. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.08.049. Epub 2017 Sep 8 [PubMed PMID: 28890048]