Introduction

With little bony constraint, the glenohumeral joint is the most unstable in the human body. Cases of anterior shoulder instability can be found in literature dating back to the time of Hippocrates. However, posterior shoulder instability was not reported in the literature until 1741 by White et al.[1] In 1952, Mclaughlin noted the wide clinical spectrum of posterior shoulder instability ranging from recurrent posterior subluxation to locked posterior dislocations.[2] Confusion in the literature surrounding the terms ensued until 1984 when Hawkins et al. clarified a distinction between fixed dislocations and recurrent subluxations, noting that compared to subluxations, recurrent posterior dislocations are extremely rare.

Posterior instability is less common than anterior instability but is increasingly recognized in the athletic population due to a better understanding of the underlying pathophysiology and the ability to treat with arthroscopic procedures.[3] A patient may present with posterior instability after sustaining a traumatic dislocation or with posterior shoulder pain secondary to blunt trauma to the shoulder. However, more commonly, patients present with vague symptoms of shoulder pain, making the diagnosis difficult. The diagnosis is largely centered around history and physical examination findings, and clinicians must maintain a high index of suspicion. Depending on the underlying etiology and pathology, treatment of posterior shoulder instability ranges from physical therapy to operative intervention. Historically, surgical treatment was done via open procedures; however, arthroscopic management is quickly becoming the treatment of choice.

Anatomy

The shoulder joint is the least congruent joint in the body with the joint commonly described as resembling a golf ball on a tee. In fact, only about one-third of the humeral head articulates with the glenoid at any given time.[4][5] This lack of bony constraint provides the shoulder with a great range of motion for everyday activities. The stability of the shoulder thus relies upon a dynamic interplay of static and dynamic stabilizers.

Static stabilizers of the shoulder include the glenoid labrum, which attaches to the periphery of the glenoid and increases the depth of the socket. Other static stabilizers include the articular congruity, glenohumeral ligaments, joint capsule, and negative intra-articular pressure. The most important static stabilizers against posterior translation are the posterior labrum, capsule, and the posterior inferior glenohumeral ligament (PIGHL).[6] The PIGHL plays a primary role in stabilizing the joint when the shoulder is loaded in a position of flexion and internal rotation.[7] When the shoulder is in this position, as seen in football linemen while blocking, the PIGHL is tensioned in an anteroposterior direction.[8] Controversy exists as to the role of the rotator interval in preventing posterior instability. While this structure has shown to be a static stabilizer against inferior and posterior translation while the arm is adducted, other cadaveric studies have suggested the rotator interval plays little role in the posterior stability of the shoulder.[9][10]

The rotator cuff muscles are the most important dynamic stabilizers of the shoulder. Contraction of the rotator cuff provides a concavity-compression effect of the humeral head against the glenoid aiding stability and increasing the load needed to translate the humeral head.[11] The subscapularis is of particular importance as studies have shown it to be the primary dynamic restraint to posterior translation.[8] Although their contributions vary depending on shoulder position, other dynamic stabilizers include the long head of the biceps tendon and deltoid muscle.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The etiology of recurrent posterior instability is multifactorial and complex. However, three broad processes have been implicated in the pathogenesis, including repetitive microtrauma, acute traumatic events, and atraumatic causes.[7][12][13] These three main broad categories are important to keep in mind when evaluating a patient with symptoms suggesting posterior instability. Correctly identifying the underlying etiology is also important so that treatment can be tailored to the underlying cause.

Repetitive microtrauma to the posteroinferior capsulolabral shoulder complex is the most common cause of recurrent posterior subluxation.[7] Repetitive loads cause this in the provocative position of glenohumeral flexion, adduction, and internal rotation as seen in activities such as bench-pressing, blocking in American football, and overhead sports such as swimming, tennis, and baseball.[12] This position loads the PIGHL, the posterior labrum, and the posterior capsule, which over time may lead to plastic deformation of the posteroinferior capsular pouch and laxity in addition to injury to the labrum.

Acute trauma to the shoulder may lead to recurrent posterior instability. Patients will often recall the incident prior to the onset of symptoms. These patients sustain a high impact injury to the anterior shoulder or an axial load with the shoulder in the position of flexion and internal rotation. Such injuries can be seen in American football linemen.[12] Although much less common than anterior dislocations, a posteriorly dislocated shoulder may lead to recurrent posterior instability. Posterior shoulder dislocations are seen after high-energy trauma to the shoulder, motor vehicle accidents, seizures, and electrocution. Recurrent posterior instability after trauma is secondary to either soft tissue injury of the posterior capsulolabral complex or bony defects of the glenoid and/or humeral head.

Patients may also report posterior instability with no history of trauma. This atraumatic presentation is the least common and is usually attributed to ligamentous laxity.[7] Patients with this type present with posterior shoulder pain as well as instability noted with the shoulder in provocative positions. These symptoms may even progress to affect activities of daily living.

Epidemiology

Posterior shoulder instability is much less common than anterior shoulder instability accounting for 2% to 12% of total cases of instability.[14][15][2] The incidence of anterior dislocations is 15.5 to 21.7 times more common than posterior dislocations.[16] The condition is becoming increasingly recognized in the young, athletic population such as overhead athletes, weightlifters, and American football players.[7] The typical patient is a male between the ages of twenty and thirty years who is involved with overhead or contact sports.[12]

Pathophysiology

Pathophysiology

An isolated pathologic lesion causing posterior instability is rare. Most often, the condition is multifactorial, involving several anatomic and pathologic identities. Bony abnormalities that have been implicated include increased humeral retroversion, glenoid retroversion, and glenoid hypoplasia.[17][18][19] In the absence of bony abnormality, Antoniou and Harryman state to which patho-anatomy may be linked.[14]

- Excessive capsular laxity

- Loss of integrity to the rotator interval (coracohumeral ligament and superior glenohumeral ligament)[20][11]

- Injury to the superior glenohumeral ligament

- Large capsular recess

- Disruptions of the glenolabral socket[21][11][22][23][15][13]

Several studies have also highlighted the importance of the inferior glenohumeral ligament (IGHL) in maintaining the posterior stability of the shoulder.[8][24][25][26]

Episodes of posterior instability commonly occur with the arm in mid-range of motion when the glenohumeral ligaments are not tensioned. Therefore, other pathomechanics must be involved other than the disruption of the capsuloligamentous structures. During mid-range of motion, Antonio and Harryman describe 3 mechanisms as the primary stabilizing forces of the glenohumeral joint:[14]

- Geometric conformity of the articular surfaces

- Labral contribution to the glenoid fossa depth

- Compression of the humeral head into the glenoid by muscular forces[27][28]

Disruption in any of these stabilizing mechanisms contributes to the development of posterior instability.

Controversy exists in regard to the role of the rotator interval in preventing posterior instability as cadaveric studies have yielded conflicting results. In cadaveric specimens, Harryman et al. demonstrated increased posterior and inferior translation as well as frank dislocation after selective sectioning of the rotator interval.[9] On the contrary, Mologne et al. found arthroscopic rotator interval closure did not improve posterior instability after posterior labral repair but did significantly decrease external rotation.[10]

As one of the primary static stabilizers of the shoulder, labral injury has been associated with posterior instability. A pure detachment of the posterior labrum is described as a reverse Bankart lesion. When associated with a fragment of bone resulting from a glenoid fracture, the pathology is termed a reverse bony Bankart lesion. An incomplete and concealed avulsion of the posteroinferior labrum is known as a Kim lesion, and failure to identify and address this lesion may result in persistent posterior instability.[29] With a frank posterior dislocation, a patient will often sustain an impaction fracture of the anteromedial humeral head known as a reverse Hill-Sachs lesion. Depending on size, this lesion is a risk factor for re-dislocation, and surgery is recommended.[30]

History and Physical

Clinical Presentation

The clinical presentation of a patient presenting with posterior shoulder instability can be variable and difficult to recognize as symptoms and exam findings are often nonspecific and subtle. Adding to the complexity is that most of these patients are young and involved with athletics. There may be concomitant shoulder pathology such as impingement syndrome.[31] Most commonly, patients report deep pain within the posterior aspect of the shoulder.[32][33][34] Additionally, the patient may report worsening athletic performance and decreased strength or endurance in the shoulder.[7][32][35][36] Mechanical symptoms, such as clicking or popping, can also be described.[32][31] Relatively few patients present after a posterior shoulder dislocation or traumatic injury with the arm in a provocative position. Thus, physicians must maintain a high index of suspicion when a young athlete presents with vague shoulder complaints, particularly in sports exposing the shoulder to repetitive microtraumas such as overhead athletes, swimmers, weightlifters, rowers, and American football players.[7][32] Lastly, patients should be asked about connective tissue disorders such as Ehlers-Danlos or Marfan syndrome, which signify ligamentous laxity.

Physical Exam

A thorough physical exam is necessary as the clinical entity may not be apparent in history alone. Findings can be subtle, and both shoulders should be fully examined to detect any side-to-side differences. An examination should include inspection, palpation, range-of-motion (ROM), strength testing, neurovascular tests, as well as provocative maneuvers. Typically, ROM, strength testing and neurovascular examination will be normal in patients with posterior shoulder instability.[32] Interestingly, a skin dimple present over the posteromedial deltoid of both shoulders was reported to be 62% sensitive and 92% specific for identifying posterior shoulder instability. Tenderness to palpation may be elicited over the posterior joint line and could be secondary to synovitis from multiple episodes of instability.[21] Patients should be evaluated for scapular dyskinesia as poor scapulothoracic mechanics can lead to posterior shoulder pain and weakness. Lastly, the clinician should evaluate the patient for generalized ligamentous laxity and multidirectional instability, as this may predispose the patient to instability.[37]

Examination maneuvers specific to posterior shoulder instability include the jerk test, Kim test, posterior drawer, and the load-and-shift test.[7] The jerk test may be performed with the patient standing or seated. The clinician stands next to the affected shoulder and holds the flexed elbow in one hand and grasps the distal clavicle and scapular spine in the other. The patient’s arm is brought into flexion, and internal rotation and a posterior force to the shoulder joint is applied through the elbow with one hand while the other hand applies an anterior force through the shoulder girdle. A sudden jerk, along with pain as the subluxated humeral head relocates into the glenoid signifies a positive test.

The Kim test was first reported in the literature by Kim et al. as a means to detect posteroinferior lesions of the labrum.[38] It is performed with the patient in the seated position with the arm in 90 degrees of abduction in the scapular plane. The clinician grasps the patient’s elbow with one hand and the patient’s proximal, lateral arm with the other hand. An axial force is applied by pushing on the elbow into the shoulder joint. While maintaining axial force, the patient’s arm is elevated an additional 45 degrees while the clinician simultaneously applies a posteroinferior force through the patient’s proximal arm. Sudden pain in the shoulder denotes a positive test. Kim et al. reported a 97% sensitivity for detecting posterior instability when both the jerk test and Kim test were positive.[38]

Evaluation

Plain Radiographs

Initial assessment of the shoulder should begin with plain radiographs. The views to obtain include a true AP of the scapula (Grashey), internal and external rotation views, scapular Y, and an axillary view.[37] In patients with atraumatic posterior shoulder instability, radiographs are typically normal. However, radiographs may identify a posterior dislocation, glenoid bone loss or fractures, glenoid retroversion or hypoplasia, as well as reverse Hill-Sachs lesions.[37][34]

Advanced Imaging

Advanced imaging consists of an MRI to better evaluate soft tissue pathology. Contrast enhancement [magnetic resonance arthrogram (MRA)] is the most sensitive diagnostic test for detecting posterior labral and capsular lesions.[39] In patients with posterior instability, findings may include a reverse Bankart lesion as well as posterior capsular enlargement.[40][41] Although rare, other findings may include a posterior humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligament and posterior labrum periosteal sleeve avulsion.[42] MRA is also useful in identifying a Kim lesion, which is an incomplete, concealed avulsion of the posteroinferior labrum.[29] The Kim classification can describe labral tear morphology.[43]

- Type I: incomplete detachment

- Type II: incomplete and concealed avulsion (Kim lesion)

- Type III: chondrolabral erosion

- Type IV: flap tear

Computed tomography (CT) will help to delineate bony morphology better, especially when pathology is noted on plain radiographs. CT scans are indicated when that are concerns for glenoid retroversion, fractures, or hypoplasia, as well as reverse Hill-Sachs lesions. Recognition of these bony abnormalities is important as they may have implications in treatment.

Treatment / Management

Overview

When formulating a treatment plan for a patient with symptomatic posterior shoulder instability, goals should include reducing pain, improving function, and preventing recurrence. However, determining the optimal treatment can prove challenging as management is dictated by many factors, including the underlying etiology, as well as osseous and soft tissue pathology. Furthermore, little is known on the natural history of a single traumatic posterior instability episode or of untreated posterior instability.[32] While treatment algorithms may help clinicians with management decisions, patients should be treated uniquely on a case-by-case basis.

Posterior Shoulder Dislocation

Posterior shoulder dislocations (PSD) are much less common than anterior shoulder dislocations and are usually associated with high-energy trauma or seizures.[44] PSD may be complicated by osseous lesions such as impression fractures of the humeral head (reverse Hill-Sachs lesion) or glenoid fractures. A locked or fixed PSD describes a shoulder that will not reduce because of the engagement of a defect on the humeral head with the glenoid. PSD may also be accompanied by fractures of the humeral head or tuberosities.[44]

In their systematic review of posterior shoulder dislocations, Paul et al. provide a treatment algorithm that takes into account the general health and activity of the patient as well as the size of the humeral head defect.[45] They recommend closed reduction under general anesthesia for acute dislocations less than 3 weeks with small humeral head (HH) defects. With the arm flexed, adducted, and internally rotated, cross-body traction is applied with simultaneous gentle pressure on the posterior humeral head. If closed reduction is unsuccessful, then an open or arthroscopic reduction may be attempted. Patients are then braced in 10 degrees of abduction with external rotation up to 20 degrees for 6 weeks. Nonoperative treatment is recommended for those without significant bony defects (<10% HH), no recurrent posterior instability, or those who are poor surgical candidates.[45](A1)

Operative management is reserved for those with continued posterior instability secondary to soft tissue lesions or humeral head defects.[45][44] Continued symptoms of posterior instability secondary to soft tissue defects may be treated with arthroscopic posterior stabilization. Further operative intervention is largely based on the size of the HH defect. Generally, for smaller lesions less than 25% of the HH, treatment consists of nonanatomic procedures such as the McLaughlin procedure (transfer of the subscapularis to the bony defect) or the Neer modification of this procedure (transfer of the lesser tuberosity to the defect).[44] Rotational osteotomy of the proximal humerus has been described as a means of preventing the HH defect from engaging the glenoid.[46] However, this technique is now avoided because of technical difficulty as well as the progression of osteoarthritis and the risk of humeral head avascular necrosis.[44][47](A1)

For larger HH defects, treatment includes bone grafting procedures or arthroplasty. In their review of posterior shoulder dislocations, Robinson and Aderinto recommend disimpaction of the HH defect with autogenous bone grafting if the injury is less than 2 weeks old and nonanatomic procedures if the lesion is recognized after 2 weeks.[44] Other studies suggest autografting is appropriate for defects up to 40% of the HH, although there is no consensus regarding autologous bone grafting and HH defect size.[48] Allograft reconstruction may be considered for HH defects greater than 40% with good bone quality and absence of osteoarthritis.[44][49] Arthroplasty is more commonly used with HH defects greater than 50%, deformity of the HH, or patients with arthritic changes.[44][50][51] Both hemiarthroplasty and total shoulder arthroplasty are options, with the latter reserved for cases in which the glenoid is involved.[45][44](A1)

Nonoperative Management of Posterior Shoulder Instability

A conservative approach of at least 6 months is typically the first line of treatment for patients with posterior instability, with outcomes dependent on the underlying etiology.[14][32][7][37][31][12] If the cause is atraumatic, patients tend to have better outcomes with nonsurgical treatment.[37][52] Rehabilitation should focus on proprioceptive exercises and strengthening the dynamic stabilizers of the shoulder, particularly the subscapularis. Scapulothoracic mechanics should be evaluated, as dysfunction can be a source of posterior shoulder pain.[37] Tibone and Bradley noted that 70% of athletes had subjective improvement after 6 months of conservative treatment.[53] However, the authors note that while functional disability with athletics may improve, instability is typically not eliminated.(A1)

Patients with posterior shoulder instability secondary to a traumatic event may have less success with nonoperative management.[7][54][13] In their study to evaluate muscle strengthening exercises to treat anterior, posterior, and multidirectional instability, Burkhead and Rockwood found that only 16% of patients with a traumatic etiology showed good or excellent results, while 83% of those with an atraumatic etiology showed good or excellent results.[54]

Operative Management of Posterior Shoulder Instability

The primary indication of surgical intervention is recurrent symptomatic posterior shoulder instability recalcitrant to conservative treatment. Surgery may be indicated for those with instability secondary to a traumatic etiology and identifiable soft tissue or osseous defect. Surgery is also indicated for those who remain symptomatic after an adequate trial of physical therapy with avoidance of provocative activities.[14][32][7][37][31][12] Surgical management can be broken down into procedures that address either soft tissue or bony pathology. In reality, patients may need a combination of procedures, and the optimal surgical approach remains controversial. Generally, procedures addressing bony pathology are performed open, and procedures addressing soft tissue pathology are done arthroscopically. No consensus exists in the literature regarding specific indications for each procedure, and thus clinicians must consider the optimal treatment for a patient on a case by case basis.

Open verse Arthroscopic Stabilization of Soft Tissue Defects

Several different open soft tissue procedures have been described in the literature, including:

- Subscapularis transfer[2]

- Reverse Putti-Platt procedure[55]

- Staple capsulorrhaphy[56]

- Various capsular shift techniques[57][20][23]

While good results have been obtained with open procedures for anterior instability, open treatment of posterior instability has not been proved favorable with a 30% to 70% failure rate.[7] This may be related to the fact that open posterior procedures are challenging and require larger surgical dissection, as well as the inability to visualize all the pathology related to posterior instability fully.[7][58][59](B2)

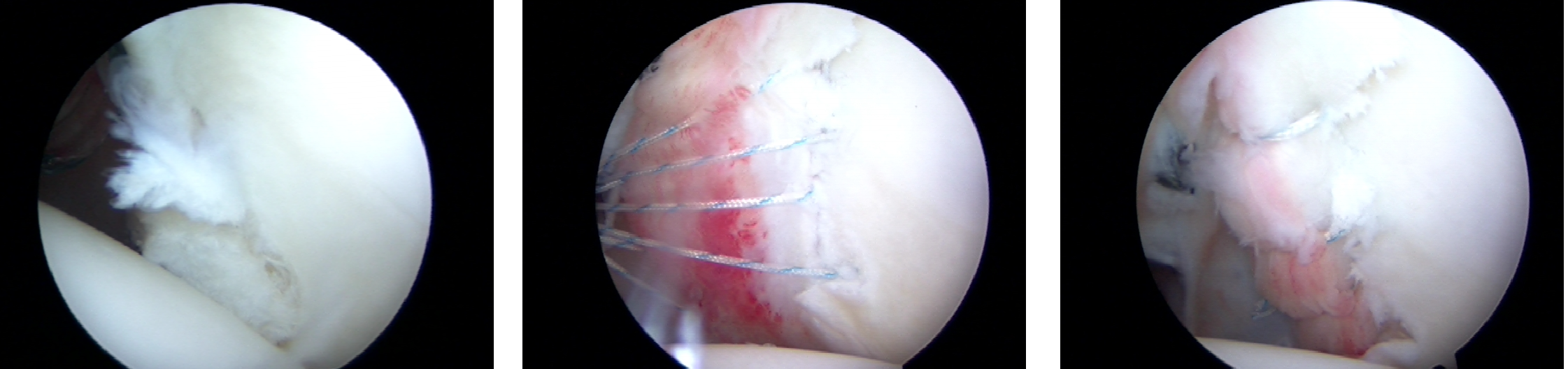

In the case of minimal bony pathology, the use of all arthroscopic treatment has surpassed open procedures for the management of posterior shoulder instability. Reasons for this include improved instrumentation and implants, less invasive nature and morbidity of arthroscopy, faster recovery, ability to view the entire labrum and to address concomitant pathology in the shoulder.[32][37][60] In the setting of a posterior labral tear, treatment generally consists of arthroscopic labral repair with suture anchors with or without capsular plication. In the case of redundant capsular tissue and no labral tear, capsular plication may be performed using sutures using either the intact labrum as the anchor point or suture anchors. Reported clinical outcomes are good to excellent with arthroscopic posterior shoulder stabilization. This approach has the highest success rates for treating posterior shoulder instability in athletes approaching 90%.[57]

When treating the patient arthroscopically, the patient is positioned in either the beach chair or lateral position, depending on surgeon preference. Generally, lateral positioning is favored as this allows more effective access to the inferior and posterior quadrants of the shoulder.[61] Labral repair is typically performed with suture anchors using three to four portals to aid in the placement and shuttling of sutures. A diagnostic arthroscopy is performed using the standard posterior portal. An anterosuperior portal is made in the superior aspect of the rotator interval, followed by a mid-glenoid portal, which aids in labral tear evaluation as well as preparation. A posterior seven o’clock portal is made 2 cm lateral and 1 cm anterior to the original posterior portal or may be described as being 2 cm directly lateral to the posterior acromial border. This portal will be used to place suture anchors in the posteroinferior glenoid, and accurate placement is crucial.[7][32][37]

The labrum can then be visualized from both the anterior and posterior portals. While viewing from the posterior portal, it is recommended to elevate and prepare the labrum from the midglenoid portal. Approaching the posterior labrum from this portal allows for a flat trajectory relative to the glenoid decreasing likelihood of chondral damage. Additionally, elevating the labrum from the posterior portal may increase the likelihood of further labral injury.[33]

The number of anchors placed is dictated by the extent of the tear and surgeon preference. For isolated posterior capsulolabral pathology, the use of three to four suture anchors spaced roughly 5 mm apart on the glenoid is usually sufficient.[7][32] These anchors can be placed using the seven o’clock portal, which provides the ideal trajectory for anchor insertion into the glenoid. Ideally, all posterior suture anchors will be placed using this portal by changing the angle of the trajectory of the anchor inserter device. Capsulolabral repair should begin with the most inferior aspect of the glenohumeral joint as the posterior shoulder joint volume diminishes with every capsulolabral stitch making each successive stitch more difficult.[7][32][37] This decrease in volume is desirable, especially in those with a patulous capsule.

A capsular plication is a technique to reduce redundant capsular tissue arthroscopically by the use of suture fixation.[61] Depending on the integrity of the labrum, this may be done with or without the use of a suture anchor. When the labrum is stable, the capsule may be anchored to the intact labrum. When there is labral pathology or a capsulolabral repair is required, a suture anchor may be used as the fixation point. Determining the amount of capsule to plicate can be difficult, but a 1 cm plication is usually sufficient.[58] The inferior and posterior capsules are important areas to address with posterior instability. Clinicians should inform their patients, especially throwing athletes, about the potential for decreased range of motion after plication, including internal rotation and abduction. Clinicians should be cautious when working in the posteroinferior capsular region to avoid injury to the axillary nerve. Dissection studies have shown the nerve to be an average of 12.4 mm from the glenoid rim at the six o’clock position.[62] Placing the shoulder in abduction and external rotation with traction during arthroscopy, the zone of safety is increased during arthroscopic plication.[63] The use of thermal devices should be avoided when working in this region.(B2)

Osseous Defects and Procedures

Patients with posterior shoulder instability may also have osseous defects, including HH impaction fractures and/or glenoid deficiency that require intervention in addition to soft tissue procedures. As previously discussed, HH defects are seen after a posterior shoulder dislocation, and if the lesion is large enough or if the patient continues to experience symptoms of instability, then intervention is required. Management of HH defects depends on the size of the lesion and includes both nonanatomic and anatomic procedures. Nonanatomic procedures include the transfer of the subscapularis into the defect on the HH as well as the Neer modification of this procedure. Anatomic reconstruction using either autograft or allograft to fill the HH defect has also been described.

Treatment for posterior instability attributable to glenoid defects such as fracture, dysplasia, or excessive retroversion may be organized into two broad categories, including posterior bone block procedure or posterior opening wedge osteotomy. Both of these procedures address posterior glenoid deficiency but may also be indicated in patients with recurrent posterior instability after soft-tissue procedures.

Posterior bone block procedures have been described in the treatment of posterior glenoid wall deficiency.[12] Fried is credited for performing the first iliac crest bone block procedure in 1949 using an iliac crest bone graft from the ipsilateral hip.[64] Several variations to this procedure have been described and are historically performed via an open posterior approach to the glenoid with the incision located in the posterior axillary fold.[57][31] Recently, the use of distal tibial allograft to treat posterior shoulder instability has been described.[65] This bone block procedure is unique in that it is intra-capsular. Studies demonstrate improved joint congruity with the humeral head compared to autogenous iliac crest bone graft.[66](B3)

Posterior glenoid opening wedge osteotomy was first published in the literature by Scott in 1967 and has been described in the treatment of excessive posterior glenoid retroversion.[12][67] It is performed through a similar posterior approach to the glenoid. The osteotomy is performed at the posteromedial glenoid neck 1 cm medial to the glenoid face.[67] The osteotomy is carefully levered open, leaving the anterior cortex intact, and the opening is filled with bone graft. The osteotomy is then secured with screws or with a plate and screws.[37](B3)

Debate exists on the amount of glenoid bone loss that necessitates a reconstructive procedure. Studies show that glenohumeral stability is compromised with glenoid articular bone loss of 20% to 25%.[68][69] Some studies have recommended glenoid reconstruction for defects greater than 25% of the width of the inferior glenoid.[57][65] In their review of posterior glenohumeral instability, Frank et al. recommend obtaining a preoperative CT scan to evaluate the amount of glenoid bone loss and determine the feasibility of arthroscopic management.[32](B2)

Differential Diagnosis

Posterior shoulder instability is an uncommon entity and can be difficult to diagnose, especially in cases involving repetitive microtrauma.[70] In patients who present with posterior shoulder pain without complaints of instability, the differential includes:

- Suprascapular nerve entrapment[71]

- Quadrilateral space syndrome[72]

- Posterior glenoid spur (Bennett lesion)[73]

- Early osteoarthritis

- Tumor[12]

Clinicians should also distinguish between laxity and symptomatic instability. Multiple studies have shown that healthy subjects may demonstrate as much glenohumeral translation as those with symptomatic instability.[14] After examination of 76 Division I collegiate athletes, Lintner et al. demonstrated that 2+ translation (translation of humeral head onto the glenoid rim) in any direction could not be considered abnormal.[74] Instability may not be isolated in one direction, and the clinician should evaluate the patient for multidirectional instability of the shoulder. A retrospective review of 231 patients found that among operatively treated cases, the incidence of isolated posterior instability and combined instability was 24% and 19%, respectively.[75]

Lastly, clinicians should also consider those with psychological problems who are able to voluntarily subluxate their shoulders. These patients may develop instability in adolescence for secondary gain and are able to willingly subluxate their shoulders with the arm at the side.[12]

Prognosis

Many factors make interpreting the literature of posterior instability challenging, including the low incidence of this clinical entity, variability in patient characteristics, surgical techniques, implants, and rehabilitation protocols, and the limited number of high-quality studies. Literature shows open surgical techniques have been reported to improve outcomes with success rates between 80% to 95%.[14][21][23] However, other studies suggest the failure rate may be as high as 50%.[37]

Initial reports of arthroscopic management of posterior instability were not as encouraging as those treated for anterior instability. However, recent literature has shown success rates of around 90% for those with posterior instability after sporting injuries.[57] Radnowski et al. analyzed arthroscopic capsulolabral repair in 107 shoulders of 98 athletes and found excellent results in 89% of throwers and 93% of non-throwing athletes at a mean of 27 months post-op. However, they noted that throwers were less likely to return to their pre-injury level of play than non-throwers (55% and 71%, respectively).[76]

In the largest patient cohort to date, Bradley et al. reported on 200 shoulders in 183 athletes prospectively treated with arthroscopic capsulolabral repair for posterior shoulder instability.[77] At a mean follow-up of 36 months postoperatively, ASES improved from 45.9 to 85.1 (P <0.001), with 90% of athletes returning to sport and 64% able to return to their previous level of play. When compared to anchorless fixation, those treated with suture anchors demonstrated significantly higher American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) scores and a higher rate of return to play.[77]

Arner et al. published a case series on 56 American football players who underwent arthroscopic posterior capsulolabral repair for posterior shoulder instability. At a mean follow-up of 44.7 months, the authors found a 93% return to sport, with 79% returning at the same level. Significant improvements were also seen on the ASES score and subjective scores of stability, ROM strength, pain, and function. The failure rate in this study was 3.5%.[78]

In 2015, DeLong et al. published a systematic review of the literature on arthroscopic and open posterior shoulder stabilization dating from 1946 to 2014.[3] Analysis of studies of open shoulder procedures containing 321 shoulders with an average follow-up of 69.8 months demonstrated a 66.4% return to play, with only 36.9% returning to the previous level of play. The average recurrence rate among the open procedures was 19.4%. Analysis of studies of arthroscopic treatment consisting of 817 shoulders at average follow up of 28.7 months postoperatively demonstrated 91.8% return to play with 67.4% returning to the previous level of play. The average recurrence rate among arthroscopic procedures was 8.1%. The authors concluded that patients undergoing arthroscopic treatment for posterior shoulder instability have superior outcomes compared to those who undergo open procedures in terms of stability, recurrence rate, patient satisfaction, return to sport, and return to the previous level of play. The authors also found that throwing athletes were less able to return to their previous level of play compared to non-throwing athletes, and repair with suture anchors resulted in fewer recurrences than those with anchorless repairs in those involved with high physical activity.[3]

Complications

Complications of posterior shoulder dislocations include osteonecrosis, posttraumatic arthritis, and joint stiffness. Osteonecrosis of the humeral head may occur after a simple dislocation but is more commonly seen with associated fracture-dislocations of the anatomic neck.[49][44] Posttraumatic arthritis is uncommon after simple dislocations. However, posttraumatic arthritis after a posterior dislocation is usually worse than arthritis seen after an anterior dislocation, and treatment may include a shoulder arthroplasty.[79] Joint stiffness after reduction is associated with a delay in diagnosis.[44] Joint stiffness may also be associated with ancillary stabilization procedures, and treatment of joint stiffness should be directed at the underlying cause.

Surgical complications for recurrent posterior shoulder instability are unique to the specific procedure performed. Complications of open treatment include infection, pain, weakness, and shoulder stiffness.[12] In regard to arthroscopic treatment, axillary nerve injury is possible, especially during the repair of the posteroinferior shoulder capsule. Thermal ablation should be avoided in this area.[63][62][80] Iatrogenic chondral damage, as well as labral transection, are also possible with poor portal placement and usage.[7][32]

The most common complication following surgical treatment of posterior shoulder instability is the recurrence of instability with rates varying depending on treatment method and cause of instability. DeLong et al. found an 8.1% rate of recurrence in over 800 shoulders treated via arthroscopic treatment as well as a recurrence rate of 19.4% in over 300 shoulders undergoing open surgical procedures.[3] Other studies analyzing the literature on arthroscopic treatment have found an average rate of recurrent instability of 5% and no higher than 10%.[12] Risk factors for recurrent instability after traumatic posterior shoulder dislocation include age below 40 at the time of dislocation, dislocation during a seizure, and a large Hill-Sachs lesion.[3] Glenoid retroversion has also been found to be an independent risk factor for recurrent instability in young athletes.[81]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Postoperative care following surgery for posterior shoulder instability involves immobilization in a shoulder brace with the arm in a position that decreases stress on the posterior soft tissues of the shoulder. Recommendations are to immobilize the shoulder in about 30 degrees of abduction and neutral rotation with care to avoid internal rotation, which puts stress on the posterior soft tissue structures.[7][37][82][83][84] Treatment protocols vary, but generally, the shoulder is immobilized for 4 to 6 weeks with patients encouraged to perform gentle active range of motion of the elbow and wrist. Passive range of motion may begin within the first several days postoperatively. Care should be taken with avoidance of internal rotation and a combination of forward flexion and internal rotation, which places tension on the posterior soft tissues.[7][84]

Active range of motion is started around 6 weeks postoperatively with strengthening programs beginning 2 to 3 months after surgery. A sport-specific rehabilitation program may be started once the patient achieves 80% strength of the contralateral shoulder, which is typically seen 6 months postoperatively.[82][77] Return to sport is determined on a case by case basis and is allowed once the athlete demonstrates pain-free full range of motion and strength in the shoulder. Most athletes may accomplish this between 6 to 9 months after surgery.[31][82]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Posterior shoulder instability is rare compared to anterior shoulder instability and is commonly misdiagnosed or overlooked. Posterior shoulder instability may arise secondary to repetitive damage to the posterior shoulder structures in young, overhead athletes or secondary to blunt trauma with the shoulder in a provocative position as seen in contact athletes. Overhead athletes should pay particular attention to their throwing mechanics and improve deficits in their kinetic chain as dysfunction has been shown to be a risk factor for reinjury after surgical stabilization.[83]

Young athletes should seek out an orthopedic specialist if he or she experiences the insidious onset of posterior shoulder pain, symptoms of instability, decreasing performance with throwing activities, or if similar symptoms develop after a traumatic episode. Athletes with symptoms secondary to repetitive microtrauma may benefit the most from nonsurgical treatment. Overhead athletes may be advised to avoid throwing activities for a minimum of 4 to 6 weeks and partake in an intensive rehabilitation program consisting of strengthening the muscles around the shoulder and correcting throwing mechanics.[83] If a young athlete requires surgery, arthroscopic treatment is now the most common procedure. Athletes treated with arthroscopic stabilization can expect a high rate of return to sport, especially if the athlete is competing in non-throwing activities.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The optimal management of patients with posterior shoulder instability requires an interdisciplinary effort, which most commonly includes athletic trainers, physical therapists, primary care physicians, and orthopedic specialists. Athletic trainers (ATCs) are often the initial point of contact with athletes who develop symptoms of posterior shoulder instability. They should have a close relationship with team physicians or other orthopedic specialists in the area to help facilitate the necessary care required for these patients. Whether seeking nonoperative management or in the postoperative period, the role of a physical therapist is vital to guiding the athlete back to play. Physical therapists will be required to detail their progression and any barriers to improvement. The orthopedic surgeon is ultimately responsible for the management of the patient’s condition and should be in close communication with their physical therapist and athletic trainer to monitor progress. [Level 5]

In the case of a posterior shoulder dislocation, other disciplines may play an important role. When a patient presents to the emergency department with a posterior shoulder dislocation, the emergency room physician must properly diagnose the condition and subsequently reduce the shoulder. The emergency room physician should direct the patient to the care of an orthopedic surgeon for further management. In patients with epilepsy causing shoulder dislocation, patients will need the care of a neurologist for anti-epileptic management. [Level 5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Loebenberg MI, Cuomo F. The treatment of chronic anterior and posterior dislocations of the glenohumeral joint and associated articular surface defects. The Orthopedic clinics of North America. 2000 Jan:31(1):23-34 [PubMed PMID: 10629330]

McLAUGHLIN HL. Posterior dislocation of the shoulder. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1952 Jul:24 A(3):584-90 [PubMed PMID: 14946209]

DeLong JM, Jiang K, Bradley JP. Posterior Instability of the Shoulder: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Clinical Outcomes. The American journal of sports medicine. 2015 Jul:43(7):1805-17. doi: 10.1177/0363546515577622. Epub 2015 Apr 10 [PubMed PMID: 25862038]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWarner JJ, Caborn DN, Berger R, Fu FH, Seel M. Dynamic capsuloligamentous anatomy of the glenohumeral joint. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery. 1993 May:2(3):115-33. doi: 10.1016/S1058-2746(09)80048-7. Epub 2009 Feb 19 [PubMed PMID: 22959404]

Warner JJ, Navarro RA. Serratus anterior dysfunction. Recognition and treatment. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 1998 Apr:(349):139-48 [PubMed PMID: 9584376]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceO'Brien SJ, Schwartz RS, Warren RF, Torzilli PA. Capsular restraints to anterior-posterior motion of the abducted shoulder: a biomechanical study. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery. 1995 Jul-Aug:4(4):298-308 [PubMed PMID: 8542374]

Provencher MT, LeClere LE, King S, McDonald LS, Frank RM, Mologne TS, Ghodadra NS, Romeo AA. Posterior instability of the shoulder: diagnosis and management. The American journal of sports medicine. 2011 Apr:39(4):874-86. doi: 10.1177/0363546510384232. Epub 2010 Dec 4 [PubMed PMID: 21131678]

Blasier RB, Soslowsky LJ, Malicky DM, Palmer ML. Posterior glenohumeral subluxation: active and passive stabilization in a biomechanical model. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1997 Mar:79(3):433-40 [PubMed PMID: 9070535]

Harryman DT 2nd, Sidles JA, Harris SL, Matsen FA 3rd. The role of the rotator interval capsule in passive motion and stability of the shoulder. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1992 Jan:74(1):53-66 [PubMed PMID: 1734014]

Mologne TS, Zhao K, Hongo M, Romeo AA, An KN, Provencher MT. The addition of rotator interval closure after arthroscopic repair of either anterior or posterior shoulder instability: effect on glenohumeral translation and range of motion. The American journal of sports medicine. 2008 Jun:36(6):1123-31. doi: 10.1177/0363546508314391. Epub 2008 Mar 4 [PubMed PMID: 18319350]

Pagnani MJ, Warren RF. Stabilizers of the glenohumeral joint. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery. 1994 May:3(3):173-90. doi: 10.1016/S1058-2746(09)80098-0. Epub 2009 Feb 19 [PubMed PMID: 22959695]

Robinson CM, Aderinto J. Recurrent posterior shoulder instability. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2005 Apr:87(4):883-92 [PubMed PMID: 15805222]

Fronek J,Warren RF,Bowen M, Posterior subluxation of the glenohumeral joint. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1989 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 2918005]

Antoniou J, Harryman DT 2nd. Posterior instability. The Orthopedic clinics of North America. 2001 Jul:32(3):463-73, ix [PubMed PMID: 11888141]

Boyd HB, Sisk TD. Recurrent posterior dislocation of the shoulder. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1972 Jun:54(4):779-86 [PubMed PMID: 5055169]

Robinson CM, Seah M, Akhtar MA. The epidemiology, risk of recurrence, and functional outcome after an acute traumatic posterior dislocation of the shoulder. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2011 Sep 7:93(17):1605-13. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.00973. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21915575]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWILSON JC, McKEEVER FM. Traumatic posterior dislocation of the humerus. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1949 Jan:31A(1):160-72 [PubMed PMID: 18122881]

Brewer BJ, Wubben RC, Carrera GF. Excessive retroversion of the glenoid cavity. A cause of non-traumatic posterior instability of the shoulder. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1986 Jun:68(5):724-31 [PubMed PMID: 3722229]

Hurley JA, Anderson TE, Dear W, Andrish JT, Bergfeld JA, Weiker GG. Posterior shoulder instability. Surgical versus conservative results with evaluation of glenoid version. The American journal of sports medicine. 1992 Jul-Aug:20(4):396-400 [PubMed PMID: 1415880]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNeer CS 2nd, Foster CR. Inferior capsular shift for involuntary inferior and multidirectional instability of the shoulder. A preliminary report. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1980 Sep:62(6):897-908 [PubMed PMID: 7430177]

Pollock RG, Bigliani LU. Recurrent posterior shoulder instability. Diagnosis and treatment. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 1993 Jun:(291):85-96 [PubMed PMID: 8504618]

Bigliani LU, Pollock RG, Soslowsky LJ, Flatow EL, Pawluk RJ, Mow VC. Tensile properties of the inferior glenohumeral ligament. Journal of orthopaedic research : official publication of the Orthopaedic Research Society. 1992 Mar:10(2):187-97 [PubMed PMID: 1740736]

Bigliani LU, Pollock RG, McIlveen SJ, Endrizzi DP, Flatow EL. Shift of the posteroinferior aspect of the capsule for recurrent posterior glenohumeral instability. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1995 Jul:77(7):1011-20 [PubMed PMID: 7608222]

Schwartz E, Warren RF, O'Brien SJ, Fronek J. Posterior shoulder instability. The Orthopedic clinics of North America. 1987 Jul:18(3):409-19 [PubMed PMID: 3327030]

Bowen MK, Warren RF. Ligamentous control of shoulder stability based on selective cutting and static translation experiments. Clinics in sports medicine. 1991 Oct:10(4):757-82 [PubMed PMID: 1934095]

O'Brien SJ, Neves MC, Arnoczky SP, Rozbruck SR, Dicarlo EF, Warren RF, Schwartz R, Wickiewicz TL. The anatomy and histology of the inferior glenohumeral ligament complex of the shoulder. The American journal of sports medicine. 1990 Sep-Oct:18(5):449-56 [PubMed PMID: 2252083]

Lazarus MD, Sidles JA, Harryman DT 2nd, Matsen FA 3rd. Effect of a chondral-labral defect on glenoid concavity and glenohumeral stability. A cadaveric model. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1996 Jan:78(1):94-102 [PubMed PMID: 8550685]

Lippitt S, Matsen F. Mechanisms of glenohumeral joint stability. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 1993 Jun:(291):20-8 [PubMed PMID: 8504601]

Kim SH, Ha KI, Yoo JC, Noh KC. Kim's lesion: an incomplete and concealed avulsion of the posteroinferior labrum in posterior or multidirectional posteroinferior instability of the shoulder. Arthroscopy : the journal of arthroscopic & related surgery : official publication of the Arthroscopy Association of North America and the International Arthroscopy Association. 2004 Sep:20(7):712-20 [PubMed PMID: 15346113]

Bock P, Kluger R, Hintermann B. Anatomical reconstruction for Reverse Hill-Sachs lesions after posterior locked shoulder dislocation fracture: a case series of six patients. Archives of orthopaedic and trauma surgery. 2007 Sep:127(7):543-8 [PubMed PMID: 17522876]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTannenbaum EP, Sekiya JK. Posterior shoulder instability in the contact athlete. Clinics in sports medicine. 2013 Oct:32(4):781-96. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2013.07.011. Epub 2013 Aug 20 [PubMed PMID: 24079434]

Frank RM, Romeo AA, Provencher MT. Posterior Glenohumeral Instability: Evidence-based Treatment. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2017 Sep:25(9):610-623. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-15-00631. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28837454]

Provencher MT, Bell SJ, Menzel KA, Mologne TS. Arthroscopic treatment of posterior shoulder instability: results in 33 patients. The American journal of sports medicine. 2005 Oct:33(10):1463-71 [PubMed PMID: 16093530]

Millett PJ, Clavert P, Hatch GF 3rd, Warner JJ. Recurrent posterior shoulder instability. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2006 Aug:14(8):464-76 [PubMed PMID: 16885478]

Bradley JP, Baker CL 3rd, Kline AJ, Armfield DR, Chhabra A. Arthroscopic capsulolabral reconstruction for posterior instability of the shoulder: a prospective study of 100 shoulders. The American journal of sports medicine. 2006 Jul:34(7):1061-71 [PubMed PMID: 16567458]

Kim SH, Ha KI, Park JH, Kim YM, Lee YS, Lee JY, Yoo JC. Arthroscopic posterior labral repair and capsular shift for traumatic unidirectional recurrent posterior subluxation of the shoulder. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2003 Aug:85(8):1479-87 [PubMed PMID: 12925627]

Brelin A, Dickens JF. Posterior Shoulder Instability. Sports medicine and arthroscopy review. 2017 Sep:25(3):136-143. doi: 10.1097/JSA.0000000000000160. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28777216]

Kim SH, Park JS, Jeong WK, Shin SK. The Kim test: a novel test for posteroinferior labral lesion of the shoulder--a comparison to the jerk test. The American journal of sports medicine. 2005 Aug:33(8):1188-92 [PubMed PMID: 16000664]

Tung GA, Hou DD. MR arthrography of the posterior labrocapsular complex: relationship with glenohumeral joint alignment and clinical posterior instability. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2003 Feb:180(2):369-75 [PubMed PMID: 12540436]

Bey MJ, Hunter SA, Kilambi N, Butler DL, Lindenfeld TN. Structural and mechanical properties of the glenohumeral joint posterior capsule. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery. 2005 Mar-Apr:14(2):201-6 [PubMed PMID: 15789015]

Dewing CB, McCormick F, Bell SJ, Solomon DJ, Stanley M, Rooney TB, Provencher MT. An analysis of capsular area in patients with anterior, posterior, and multidirectional shoulder instability. The American journal of sports medicine. 2008 Mar:36(3):515-22. doi: 10.1177/0363546507311603. Epub 2008 Jan 23 [PubMed PMID: 18216272]

Yu JS, Ashman CJ, Jones G. The POLPSA lesion: MR imaging findings with arthroscopic correlation in patients with posterior instability. Skeletal radiology. 2002 Jul:31(7):396-9 [PubMed PMID: 12107572]

Kim SH, Kim HK, Sun JI, Park JS, Oh I. Arthroscopic capsulolabroplasty for posteroinferior multidirectional instability of the shoulder. The American journal of sports medicine. 2004 Apr-May:32(3):594-607 [PubMed PMID: 15090373]

Robinson CM, Aderinto J. Posterior shoulder dislocations and fracture-dislocations. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2005 Mar:87(3):639-50 [PubMed PMID: 15741636]

Paul J, Buchmann S, Beitzel K, Solovyova O, Imhoff AB. Posterior shoulder dislocation: systematic review and treatment algorithm. Arthroscopy : the journal of arthroscopic & related surgery : official publication of the Arthroscopy Association of North America and the International Arthroscopy Association. 2011 Nov:27(11):1562-72. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2011.06.015. Epub 2011 Sep 1 [PubMed PMID: 21889868]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKeppler P, Holz U, Thielemann FW, Meinig R. Locked posterior dislocation of the shoulder: treatment using rotational osteotomy of the humerus. Journal of orthopaedic trauma. 1994 Aug:8(4):286-92 [PubMed PMID: 7965289]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWalch G,Boileau P,Martin B,Dejour H, [Unreduced posterior luxations and fractures-luxations of the shoulder. Apropos of 30 cases]. Revue de chirurgie orthopedique et reparatrice de l'appareil moteur. 1990; [PubMed PMID: 2151476]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKhayal T, Wild M, Windolf J. Reconstruction of the articular surface of the humeral head after locked posterior shoulder dislocation: a case report. Archives of orthopaedic and trauma surgery. 2009 Apr:129(4):515-9. doi: 10.1007/s00402-008-0762-z. Epub 2008 Sep 25 [PubMed PMID: 18815798]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGerber C,Lambert SM, Allograft reconstruction of segmental defects of the humeral head for the treatment of chronic locked posterior dislocation of the shoulder. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1996 Mar; [PubMed PMID: 8613444]

Hawkins RJ, Neer CS 2nd, Pianta RM, Mendoza FX. Locked posterior dislocation of the shoulder. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1987 Jan:69(1):9-18 [PubMed PMID: 3805075]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceChecchia SL, Santos PD, Miyazaki AN. Surgical treatment of acute and chronic posterior fracture-dislocation of the shoulder. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery. 1998 Jan-Feb:7(1):53-65 [PubMed PMID: 9524341]

McIntyre K,Bélanger A,Dhir J,Somerville L,Watson L,Willis M,Sadi J, Evidence-based conservative rehabilitation for posterior glenohumeral instability: A systematic review. Physical therapy in sport : official journal of the Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Sports Medicine. 2016 Nov; [PubMed PMID: 27665529]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceTibone JE, Bradley JP. The treatment of posterior subluxation in athletes. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 1993 Jun:(291):124-37 [PubMed PMID: 8504591]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBurkhead WZ Jr,Rockwood CA Jr, Treatment of instability of the shoulder with an exercise program. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1992 Jul; [PubMed PMID: 1634579]

SEVERIN E. Anterior and posterior recurrent dislocation of the shoulder: the Putti-Platt operation. Acta orthopaedica Scandinavica. 1953:23(1):14-22 [PubMed PMID: 13147784]

DU TOIT GT,ROUX D, Recurrent dislocation of the shoulder; a twenty-four year study of the Johannesburg stapling operation. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1956 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 13286259]

DiMaria S,Bokshan SL,Nacca C,Owens B, History of surgical stabilization for posterior shoulder instability. JSES open access. 2019 Dec; [PubMed PMID: 31891038]

Wolf EM, Eakin CL. Arthroscopic capsular plication for posterior shoulder instability. Arthroscopy : the journal of arthroscopic & related surgery : official publication of the Arthroscopy Association of North America and the International Arthroscopy Association. 1998 Mar:14(2):153-63 [PubMed PMID: 9531126]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHawkins RJ,Janda DH, Posterior instability of the glenohumeral joint. A technique of repair. The American journal of sports medicine. 1996 May-Jun; [PubMed PMID: 8734875]

Tjoumakaris FP, Bradley JP. The rationale for an arthroscopic approach to shoulder stabilization. Arthroscopy : the journal of arthroscopic & related surgery : official publication of the Arthroscopy Association of North America and the International Arthroscopy Association. 2011 Oct:27(10):1422-33. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2011.06.006. Epub 2011 Aug 26 [PubMed PMID: 21872422]

Hewitt M, Getelman MH, Snyder SJ. Arthroscopic management of multidirectional instability: pancapsular plication. The Orthopedic clinics of North America. 2003 Oct:34(4):549-57 [PubMed PMID: 14984194]

Price MR,Tillett ED,Acland RD,Nettleton GS, Determining the relationship of the axillary nerve to the shoulder joint capsule from an arthroscopic perspective. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2004 Oct; [PubMed PMID: 15466721]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceUno A, Bain GI, Mehta JA. Arthroscopic relationship of the axillary nerve to the shoulder joint capsule: an anatomic study. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery. 1999 May-Jun:8(3):226-30 [PubMed PMID: 10389077]

FRIED A. Habitual posterior dislocation of the shoulder-joint; a report on five operated cases. Acta orthopaedica Scandinavica. 1948-49:18(3):329-45 [PubMed PMID: 18144614]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMillett PJ, Schoenahl JY, Register B, Gaskill TR, van Deurzen DF, Martetschläger F. Reconstruction of posterior glenoid deficiency using distal tibial osteoarticular allograft. Knee surgery, sports traumatology, arthroscopy : official journal of the ESSKA. 2013 Feb:21(2):445-9. doi: 10.1007/s00167-012-2254-5. Epub 2012 Nov 1 [PubMed PMID: 23114865]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFrank RM, Shin J, Saccomanno MF, Bhatia S, Shewman E, Bach BR Jr, Wang VM, Cole BJ, Provencher MT, Verma NN, Romeo AA. Comparison of glenohumeral contact pressures and contact areas after posterior glenoid reconstruction with an iliac crest bone graft or distal tibial osteochondral allograft. The American journal of sports medicine. 2014 Nov:42(11):2574-82. doi: 10.1177/0363546514545860. Epub 2014 Sep 5 [PubMed PMID: 25193887]

Scott DJ Jr. Treatment of recurrent posterior dislocations of the shoulder by glenoplasty. Report of three cases. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1967 Apr:49(3):471-6 [PubMed PMID: 6022356]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGerber C, Nyffeler RW. Classification of glenohumeral joint instability. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2002 Jul:(400):65-76 [PubMed PMID: 12072747]

Hovelius LK, Sandström BC, Rösmark DL, Saebö M, Sundgren KH, Malmqvist BG. Long-term results with the Bankart and Bristow-Latarjet procedures: recurrent shoulder instability and arthropathy. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery. 2001 Sep-Oct:10(5):445-52 [PubMed PMID: 11641702]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceCarbonell-Escobar R, Vaquero-Picado A, Barco R, Antuña S. Neurologic complications after surgical management of complex elbow trauma requiring radial head replacement. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery. 2020 Jun:29(6):1282-1288. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2020.01.086. Epub 2020 Apr 10 [PubMed PMID: 32284308]

Cummins CA, Messer TM, Nuber GW. Suprascapular nerve entrapment. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2000 Mar:82(3):415-24 [PubMed PMID: 10724234]

Cahill BR, Palmer RE. Quadrilateral space syndrome. The Journal of hand surgery. 1983 Jan:8(1):65-9 [PubMed PMID: 6827057]

Ferrari JD, Ferrari DA, Coumas J, Pappas AM. Posterior ossification of the shoulder: the Bennett lesion. Etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. The American journal of sports medicine. 1994 Mar-Apr:22(2):171-5; discussion 175-6 [PubMed PMID: 8198183]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLintner SA,Levy A,Kenter K,Speer KP, Glenohumeral translation in the asymptomatic athlete's shoulder and its relationship to other clinically measurable anthropometric variables. The American journal of sports medicine. 1996 Nov-Dec; [PubMed PMID: 8947390]

Song DJ, Cook JB, Krul KP, Bottoni CR, Rowles DJ, Shaha SH, Tokish JM. High frequency of posterior and combined shoulder instability in young active patients. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery. 2015 Feb:24(2):186-90. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2014.06.053. Epub 2014 Sep 11 [PubMed PMID: 25219471]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRadkowski CA, Chhabra A, Baker CL 3rd, Tejwani SG, Bradley JP. Arthroscopic capsulolabral repair for posterior shoulder instability in throwing athletes compared with nonthrowing athletes. The American journal of sports medicine. 2008 Apr:36(4):693-9. doi: 10.1177/0363546508314426. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18364459]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBradley JP, McClincy MP, Arner JW, Tejwani SG. Arthroscopic capsulolabral reconstruction for posterior instability of the shoulder: a prospective study of 200 shoulders. The American journal of sports medicine. 2013 Sep:41(9):2005-14. doi: 10.1177/0363546513493599. Epub 2013 Jun 26 [PubMed PMID: 23804588]

Arner JW, McClincy MP, Bradley JP. Arthroscopic Stabilization of Posterior Shoulder Instability Is Successful in American Football Players. Arthroscopy : the journal of arthroscopic & related surgery : official publication of the Arthroscopy Association of North America and the International Arthroscopy Association. 2015 Aug:31(8):1466-71. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2015.02.022. Epub 2015 Apr 14 [PubMed PMID: 25882177]

Samilson RL, Prieto V. Dislocation arthropathy of the shoulder. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1983 Apr:65(4):456-60 [PubMed PMID: 6833319]

Greis PE, Burks RT, Schickendantz MS, Sandmeier R. Axillary nerve injury after thermal capsular shrinkage of the shoulder. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery. 2001 May-Jun:10(3):231-5 [PubMed PMID: 11408903]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOwens BD, Campbell SE, Cameron KL. Risk factors for posterior shoulder instability in young athletes. The American journal of sports medicine. 2013 Nov:41(11):2645-9. doi: 10.1177/0363546513501508. Epub 2013 Aug 27 [PubMed PMID: 23982394]

Bäcker HC, Galle SE, Maniglio M, Rosenwasser MP. Biomechanics of posterior shoulder instability - current knowledge and literature review. World journal of orthopedics. 2018 Nov 18:9(11):245-254. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v9.i11.245. Epub 2018 Nov 18 [PubMed PMID: 30479971]

Chang ES, Greco NJ, McClincy MP, Bradley JP. Posterior Shoulder Instability in Overhead Athletes. The Orthopedic clinics of North America. 2016 Jan:47(1):179-87. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2015.08.026. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26614932]

Sanchez G, Kennedy NI, Ferrari MB, Mannava S, Frangiamore SJ, Provencher MT. Arthroscopic Labral Repair in the Setting of Recurrent Posterior Shoulder Instability. Arthroscopy techniques. 2017 Oct:6(5):e1789-e1794. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2017.06.055. Epub 2017 Oct 9 [PubMed PMID: 29430388]