Anatomy, Head and Neck, Posterior Humeral Circumflex Artery

Anatomy, Head and Neck, Posterior Humeral Circumflex Artery

Introduction

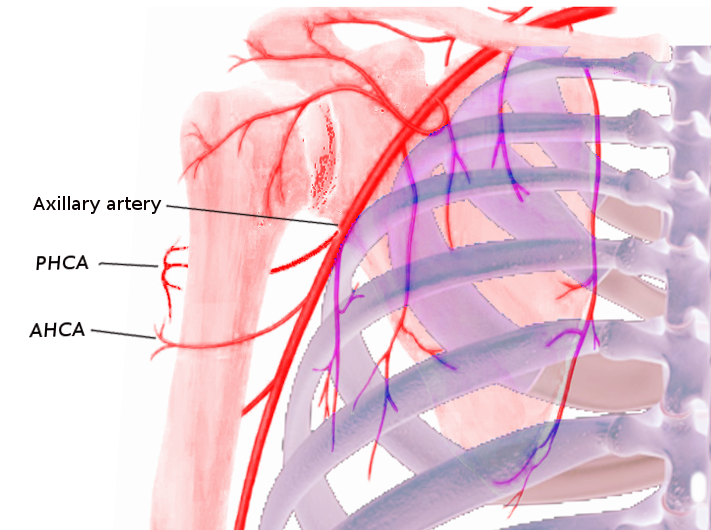

The posterior humeral circumflex artery (PHCA) originates from the third part of the axillary artery immediately posterior to the origin of the anterior humeral circumflex artery (AHCA). The PHCA and other neurovascular structures leave the axilla by passing through the quadrangular space between the teres major and minor muscles, the long head of the triceps brachii muscle, and the surgical neck of the humerus.[1][2]

After the PHCA passes through the quadrangular space, it curves around the surgical neck of the humerus and supplies the surrounding muscles and the shoulder joint. It also forms rich anastomoses with the AHCA and branches from the profunda brachii, suprascapular, and thoracoacromial arteries.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The axillary artery is a large vessel that supplies the axilla, lateral thorax, and upper limb with arterial blood. It divides into three parts by the pectoralis minor muscle[3]. The PHCA arises from the third part of the axillary artery, which is distal to the lower border of the pectoralis minor muscle and anterior to the subscapularis and teres major muscles. As an aside, the other two branches that originate from the third part of the axillary artery include the subscapular trunk and the AHCA. The AHCA, which is the smaller artery of the two, forms anastomoses with the PHCA to supply the humeral head.[1] The latter serves as the predominant blood supply to the humeral head[4][5]. Other anastomoses that connect to the PHCA include branches from the profunda brachii, suprascapular, and thoracoacromial arteries.

Along with the axillary nerve and its associated vein, the PHCA leaves the axilla and enters the posterior scapular region by passing through the quadrangular space, which is bounded by the borders of the teres major inferiorly, teres minor superiorly, the long head of triceps brachii medially, and the surgical neck of the humerus laterally.[2] The PHCA itself divides into anterior and posterior branches within the quadrangular space. It eventually wraps anteriorly around the surgical neck of the humerus to provide blood supply to the superior, inferior, and lateral portions of the humeral head, the glenohumeral joint, and the surrounding shoulder muscles.[6][7] These arterial branches also curve around the surgical neck of the humerus before supplying about two-thirds of the entire blood supply to the humeral head. The remaining 36% of the blood supply to the humeral head comes from the AHCA. Because the PHCA provides the predominant blood supply, there relatively low rates of osteonecrosis seen in displaced fractures of the proximal humerus.[8]

Embryology

The development of the arteries of the upper limb closely correlates with upper limb development. The upper limb bud develops from a group of activated mesenchymal cells in the lateral mesoderm and begins to form towards the end of the fourth week. Each limb bud is made up of a mass of mesenchyme that remains undifferentiated until it is ready to develop into other structures such as bone, cartilage, and blood vessels later in development.[9]

The PHCA develops from the branches of the primary axial artery as it develops. The primary axial artery, which later forms the brachial artery, arises as the lateral branch of the seventh intersegmental artery from the dorsal aorta. This artery grows and branches out at approximately the same rate as does the limb bud. As the primary axis artery grows outward along the axial line, its proximal part forms the brachial and axillary arteries, and, subsequently, the PHCA.[10]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The venous drainage of the PHCA comes from its accompanying vein. The posterior humeral circumflex vein, which arises as a branch of the axillary vein, travels with the axillary nerve and the PHCA through the quadrangular space to supply the surrounding structures.

The lymphatics of the upper limb drain into the axillary lymph nodes. There are about 20 to 30 total axillary lymph nodes that subdivide into five main groups based on location: humeral (lateral), pectoral (anterior), subscapular (posterior), central, and apical nodes. The lymph nodes that pertain to the PHCA and its associated structures are the humeral lymph nodes. These lymph nodes are located in the lateral wall of the axilla and are posteromedial to the axillary vein. In general, they receive lymph from the majority of the upper limb. The subclavian lymphatic trunk drains lymphatics of the shoulder and axilla. The lymphatic drainage from the subclavian trunk in the right upper limb enters the right venous angle and drains into the right lymphatic duct whereas the lymphatic drainage from the left drains directly into the thoracic duct.[11][12]

Nerves

The axillary nerve, which branches from the posterior cord of the brachial plexus as C5 to C6 contributions, runs superior to the PHCA as they travel together through the quadrangular space. The axillary nerve then splits into an anterior and posterior branch as it courses distally to provide motor and sensory innervation to the shoulder muscles and the overlying skin. More specifically, the anterior branch of the axillary nerve provides the motor innervation to the anterior deltoid muscle and the sensory innervation to the overlying skin. The posterior branch provides the motor innervation the posterior deltoid muscle and the teres minor muscle and the sensory innervation to the skin overlying the distal deltoid muscle and proximal triceps.[13] The posterior branch also gives off the superolateral brachial cutaneous nerve, which innervates the distal two-thirds of the posterior deltoid. Together, both the anterior and posterior branches innervation the middle third of the deltoid muscle as well as the shoulder joint capsule.[2][6][7]

Muscles

The anterior and posterior branches of the PHCA supply the shoulder muscles, which include the deltoid muscle, the teres major, and teres minor muscles.[6][7]

Physiologic Variants

Anatomical variants of the PHCA are very rare, but there are reports in some studies. Multiple case reports have documented the unusual origin of the PHCA coming off the subscapular artery as either a branch of the first or the second part of the axillary artery compared to the normal anatomy in which it branches off of the third part of the axillary artery with the subscapular trunk as an individual branch.[14][15][16] Another study describes a case where the PHCA arises from the third part of the axillary artery, but as a branch of the deep brachial artery rather than its normal variant of being a direct branch itself.[17] Interestingly, most of these studies have identified these anomalies as phenomena that occur unilaterally.

Aside from variations in its origin, other studies have reported variations in its course and the branches that come off the PHCA. One study reported a case in which the PHCA, accompanied by the axillary nerve and its associated vein, passes through the lower triangular space to reach the scapular region rather than its normal descent through the quadrangular space. The same study also reported an unusual origin of the radial collateral artery arising from the PCHA that can mimic symptoms of quadrangular space syndrome.[18] Another study discussed the variations in the number of terminal branches that come off the PHCA. The study revealed that 92% of patients, out of a total of 92 patients, had a terminal branch that crossed the space between the deltoid and the proximal humerus. The majority of patients were found to have a single vessel branch variant (75%), followed by double vessel variants (16%), and last, triple vessel variants. This finding has important implications during a deltopectoral surgical approach to the shoulder as these vessels are vulnerable to tearing and can cause persistent bleeding leading to prolonged surgery and postoperative hematoma and infection.[19]

Surgical Considerations

Quadrilateral space syndrome (QSS)

QSS occurs secondary to compression or mechanical injury to the axillary nerve and/or PHCA. Involvement of the PHCA results in vascular QSS, which most often occurs secondary to repetitive mechanical trauma in a predisposed or already compromised tight quadrangular space as the PHCA wraps around the humeral neck during abduction and external rotation shoulder movements. Patients develop PHCA thrombosis and/or aneurysm with distal embolization and digital ischemia[20]. The vascular form of QSS is treated with PHCA ligation to prevent distal embolization. Acute thrombotic embolization management is with thrombolytic modalities.

Proximal humerus fractures

In the case of managing proximal humeral fractures, one study identified anatomic landmarks for establishing quick access to the PHCA and AHCA as an effort to aid protection of the arteries during surgical fixation. The same study reported that the mean distances from the origin of PHCA arising from the third part of the axillary artery to the infraglenoid tubercle, the coracoid, the acromion, and the midclavicular line were 27.7 mm, 50.2 mm, 68.4 mm and 75.8 mm, respectively. Similarly, the mean distances from the origin of ACHA to the same landmarks were 26.9 mm, 49.2 mm, 67.0 mm and 74.9 mm.[21]

Clinical Significance

Injuries to the PHCA are uncommon but may occur as a result of compression or disruption secondary to trauma.

- Vascular quadrangular space syndrome (vQSS) is an underdiagnosed cause of ischemia in the upper extremities of overhead throwing athletes less than 40 years old who are otherwise healthy. The mechanism of vQSS is still unclear but is thought to result from impingement of the neurovascular structures within the quadrangular space due to trauma, fibrous bands, or hypertrophy of a muscular border. Other rare causes include labral cysts, hematomas secondary to fracture, osteochondroma, lipomas, axillary schwannomas, the existence of anatomic variations and accessory muscles, and as a rare complication of thoracic surgery. Axillary nerve compression or repeated arm abduction and external rotation from overhead activities (i.e., swimming, baseball, volleyball) may also cause distraction injury of the PHCA as it courses through the quadrangular space causing dissection and aneurysm formation. Embolism may occur as a thrombus from this arterial injury travels down the arm and results in the symptomatic presentation of ischemia which includes pain, pallor, paresthesias, diminished or absent distal pulses, cyanosis, and coolness of the digits and hand. Later stages of presentation may include ischemic ulceration and gangrene. Early recognition and awareness of this syndrome among coaches and athletic trainers are essential to optimal treatment. Initial therapy involves physical therapy, physical activity modification, NSAID use, and maybe even perineural steroid injections. Surgical decompression is recommended when patients are unresponsive to conservative measures for at least 6 months and depends on the extent of damage to the PHCA. Patients with a PHCA aneurysm undergo surgical resection. Patients with a thrombus undergo PHCA ligation and division with or without thrombolysis. Last, patients who have a thrombus in their PHCA and digital emboli usually undergo thromboembolectomy. When treated early and promptly, athletes may return to baseline.[2][22][23]

- The PHCA may also suffer disruption in the case of a proximal humeral fracture and dislocation, which can lead to a life-threatening hemorrhagic complication during surgical fixation. Obtaining earlier angiographic studies is imperative in the course of management and treatment of this condition.[24]

Media

References

Thiel R, Munjal A, Daly DT. Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Axillary Artery. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29489298]

Khan IA, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Arm Quadrangular Space. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30726009]

Galley IJ, Watts AC, Bain GI. The anatomic relationship of the axillary artery and vein to the clavicle: a cadaveric study. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery. 2009 Sep-Oct:18(5):e21-5. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2009.01.021. Epub 2009 Apr 11 [PubMed PMID: 19362855]

Mostafa E, Imonugo O, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Humerus. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30521242]

Pencle FJ, Varacallo M. Proximal Humerus Fracture. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29262220]

Juneja P, Hubbard JB. Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Arm Teres Minor Muscle. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30020696]

Elzanie A, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Deltoid Muscle. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30725741]

Hettrich CM, Boraiah S, Dyke JP, Neviaser A, Helfet DL, Lorich DG. Quantitative assessment of the vascularity of the proximal part of the humerus. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2010 Apr:92(4):943-8. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.01144. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20360519]

Tang A, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Hand Carpal Bones. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30571003]

Epperson TN, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Brachial Artery. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30725830]

Cowan PT, Mudreac A, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Back, Scapula. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30285370]

Chang LR, Anand P, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Glenohumeral Joint. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30725703]

Epstein MD, Bhargava P, Medverd JR. A 48-year-old man with chronic right shoulder pain and weakness after a fall: diagnosis and discussion. Post-traumatic chronic axillary nerve injury. Skeletal radiology. 2010 May:39(5):505-6, 489-90. doi: 10.1007/s00256-009-0841-4. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20127326]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGoldman EM, Shah YS, Gravante N. A case of an extremely rare unilateral subscapular trunk and axillary artery variation in a male Caucasian: comparison to the prevalence within other populations. Morphologie : bulletin de l'Association des anatomistes. 2012 Aug:96(313):23-8. doi: 10.1016/j.morpho.2012.03.001. Epub 2012 Sep 27 [PubMed PMID: 23022199]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBaral P, Vijayabhaskar P, Roy S, Kumar S, Ghimire S, Shrestha U. Multiple arterial anomalies in upper limb. Kathmandu University medical journal (KUMJ). 2009 Jul-Sep:7(27):293-7 [PubMed PMID: 20071879]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDurgun B, Yücel AH, Kizilkanat ED, Dere F. Multiple arterial variation of the human upper limb. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2002 May:24(2):125-8 [PubMed PMID: 12197022]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCavdar S, Zeybek A, Bayramiçli M. Rare variation of the axillary artery. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2000:13(1):66-8 [PubMed PMID: 10617889]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMohandas Rao KG, Somayaji SN, Ashwini LS, Ravindra S, Abhinitha P, Rao A, Sapna M, Jyothsna P. Variant course of posterior circumflex humeral artery associated with the abnormal origin of radial collateral artery: could it mimic the quadrangular space syndrome? Acta medica Iranica. 2012:50(8):572-6 [PubMed PMID: 23109033]

Smith CD, Booker SJ, Uppal HS, Kitson J, Bunker TD. Anatomy of the terminal branch of the posterior circumflex humeral artery: relevance to the deltopectoral approach to the shoulder. The bone & joint journal. 2016 Oct:98-B(10):1395-1398 [PubMed PMID: 27694595]

Brown SA, Doolittle DA, Bohanon CJ, Jayaraj A, Naidu SG, Huettl EA, Renfree KJ, Oderich GS, Bjarnason H, Gloviczki P, Wysokinski WE, McPhail IR. Quadrilateral space syndrome: the Mayo Clinic experience with a new classification system and case series. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2015 Mar:90(3):382-94. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.12.012. Epub 2015 Jan 31 [PubMed PMID: 25649966]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceChen YX, Zhu Y, Wu FH, Zheng X, Wangyang YF, Yuan H, Xie XX, Li DY, Wang CJ, Shi HF. Anatomical study of simple landmarks for guiding the quick access to humeral circumflex arteries. BMC surgery. 2014 Jun 26:14():39. doi: 10.1186/1471-2482-14-39. Epub 2014 Jun 26 [PubMed PMID: 24970300]

Hangge PT, Breen I, Albadawi H, Knuttinen MG, Naidu SG, Oklu R. Quadrilateral Space Syndrome: Diagnosis and Clinical Management. Journal of clinical medicine. 2018 Apr 21:7(4):. doi: 10.3390/jcm7040086. Epub 2018 Apr 21 [PubMed PMID: 29690525]

Rollo J, Rigberg D, Gelabert H. Vascular Quadrilateral Space Syndrome in 3 Overhead Throwing Athletes: An Underdiagnosed Cause of Digital Ischemia. Annals of vascular surgery. 2017 Jul:42():63.e1-63.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2016.10.051. Epub 2017 Mar 8 [PubMed PMID: 28284923]

Gorthi V, Moon YL, Jo SH, Sohn HM, Ha SH. Life-threatening posterior circumflex humeral artery injury secondary to fracture-dislocation of the proximal humerus. Orthopedics. 2010 Mar:33(3):. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20100129-29. Epub 2010 Mar 10 [PubMed PMID: 20349876]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence