Introduction

Delirium is a neurocognitive syndrome caused by reversible neuronal disruption due to an underlying systemic perturbation. It is a form of acute end-organ dysfunction which can be used as a marker of brain dysfunction. The fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) published by the American Psychiatric Association establishes diagnostic criteria and descriptions to guide the classification and diagnosis of mental disorders. According to DSM-5, diagnostic criteria for delirium include a disturbance in attention, cognition and/or awareness that develops over a short period and has a fluctuating course.[1] The alterations in brain function should differ from the patient's baseline brain function. Experts have identified three types of delirium namely, hyperactive, hypoactive, and mixed varieties.

Post-operative delirium (POD) can occur from 10 minutes after anesthesia to up to 7 days in the hospital or until discharge. It is commonly recognized in the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU) as sudden, fluctuating, and usually reversible disturbance of mental status with some degree of inattention. Severely reduced arousal or deep sedation should not be confused with alterations in brain function. Hypoactive delirium is the most common form of POD.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Delirium may be due to exacerbation of a primary injury or insult, or a potential new secondary insult or injury. Several studies have tried to identify risk factors predisposing to the development of delirium postoperatively.

DSM-5 categorizes delirium as:

- Substance Intoxication delirium

- Substance withdrawal delirium

- Medication-induced delirium

- Delirium because of other medical conditions

- Delirium because of other etiologies

POD should be considered a separate category. The post-operative period is the time period right after surgery until the patient is discharged from the hospital. POD should not be diagnosed separately from emergence delirium although any lucid interval after emergence delirium should be noted.[1]

Factors that can predispose or precipitate post-operative delirium can be broadly divided into preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative causes.[2]

Pre-Operative Factors

- Age over 65 years

- Male gender

- Baseline cognitive dysfunction

- Dementia

- Preoperative memory complaint

- Anxiety

- Depression

- Benzodiazepine use

- Intracranial stenosis

- Carotid stenosis

- Peripheral vascular disease

- Prior stroke/transient ischemic attacks

- Sensory impairments

- Diabetes mellitus

- Hypertension

- Atrial fibrillation

- Electrolyte abnormalities

- Alcohol abuse

- Sleep deprivation

- Smoking

Intraoperative Factors

- Hip surgery

- Cardiac surgery

- Vascular surgery

- Open greater than endovascular surgery

- Emergency surgery

- Increased Surgical duration

- Hypotension

- Shock

- Arrhythmias

- Hypothermia/hyperthermia

- Blood Transfusion

Postoperative Factors

- Low hemoglobin

- Hypoxemia

- Prolonged intubation

- Pain

- Hypoalbuminemia

- Liver failure

- Renal failure (BUN/Cr greater than 18)

- Sleep-wake disturbances

Alcohol and benzodiazepine withdrawal have also been known to cause POD.

Epidemiology

POD is common, and the prevalence increases with the severity of the surgical insult. According to DSM-5, the incidence of POD in non-cardiac surgery is anywhere between 15% and 54% depending on the screening test used. The incidence in the intensive care population is up to 70% to 80% during their entire stay. In cardiac surgery patients, the incidence is similarly high, between 26% and 52%.[1]

While the incidence of POD is common and similar to other settings, there is a wide discrepancy in the literature regarding the incidence, partly due to the lack of clearly defined distinction between emergence delirium and POD. Prior studies have focused on hyperactive delirium, typically recognized as the patient in the PACU pulling at lines and tubes and being agitated, likely under-diagnosing hypoactive delirium, the most common, which is characterized by lethargy, decreased responsiveness and decreased activity level. This type will often go undiagnosed if routine delirium monitoring is not used.[3]

Despite these limitations, the incidence and risk factors of POD reported in the literature is strongly influenced by the severity of the surgical insult, comorbidities, and sedative and/or analgesic drug exposure.

Pathophysiology

Although the International Study of Post-Operative Cognitive Dysfunction 1 (ISPOCD1) concluded that general anesthesia is responsible for postoperative cognitive dysfunction (POCD), later studies showed a similar incidence in sedation and regional anesthesia cases.[4][5] Both surgery and anesthesia present patients with unique physiological conditions. Surgery causes the release of psychoactive inflammatory markers including interleukin 6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) and IL-1 beta that may contribute to the development of delirium through dopamine, GABA, or cholinergic-mediated pathways. On the other hand, general anesthesia exposes the brain to a myriad of cognitively active drugs that alter the chemical balance in the sleep/arousal pathway. The incidence of delirium is lower in patients exposed to light sedation compared to deep sedation.[6]

History and Physical

The patient can present with hyperactive psychomotor activity and frank psychosis in a hyperactive variety or as withdrawal and lethargy which can easily be mistaken for residual anesthetic effects, in hypoactive variety. Other common features include a fluctuating level of consciousness, disorientation, and impaired executive function.[7]

Evaluation

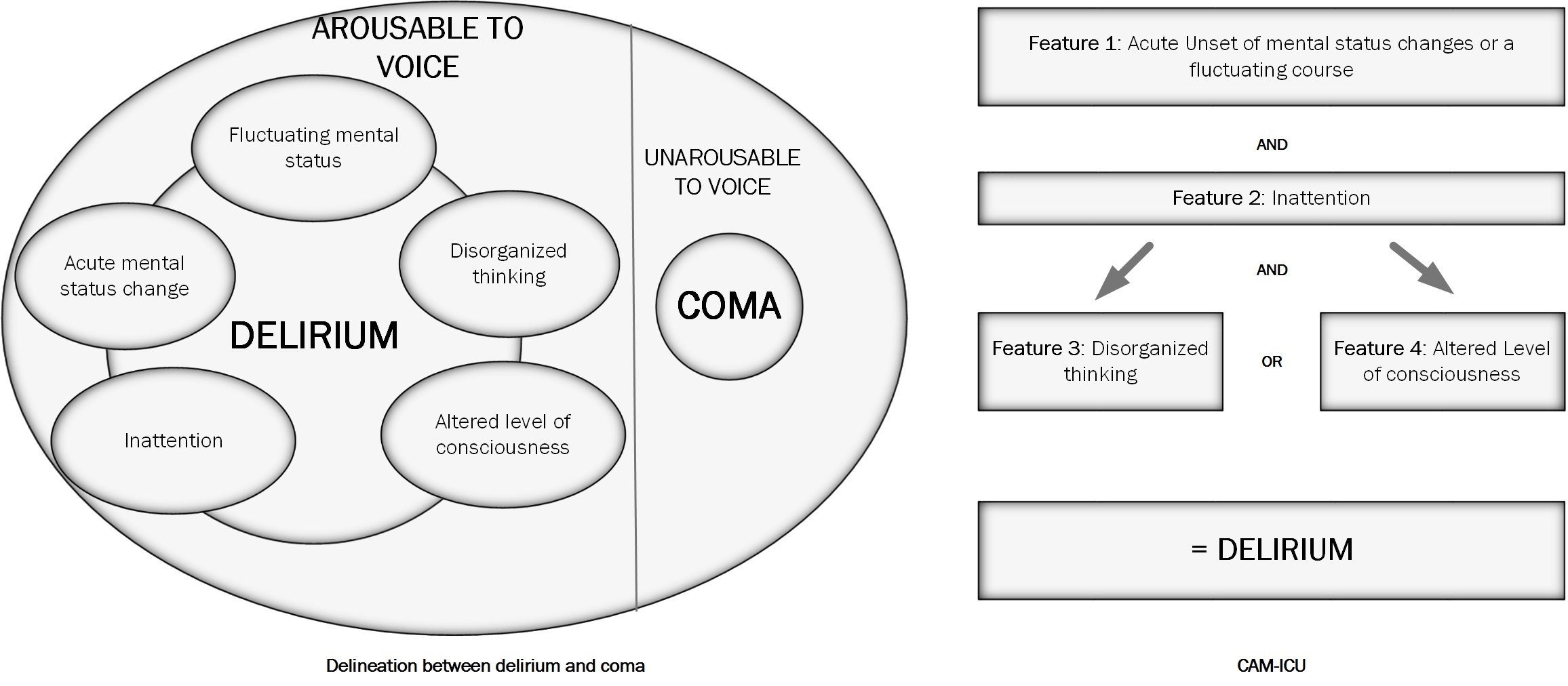

The first step in the evaluation of POD is to determine if the person is arousable to voice. If the person is not arousable to voice, then that person is considered to be in a coma. After the level of arousal has been determined, the delirium instruments can assess the content of the arousal by examining for fluctuating change in mental status highlighted by inattention and altered level of consciousness.[8]

The Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale (RASS) is the most commonly used assessment tool for the level of arousal.[9] Patients in a state of deep sedation or patients who are unarousable cannot be further assessed for delirium.

Using the DSM-5 criteria, delirium is characterized by:

- A disturbance in attention (reduced ability to direct, focus, sustain, and shift attention) and awareness (reduced orientation to the environment).

- A disturbance that develops over a short period (usually hours to a few days) represents a change from baseline attention and awareness and fluctuates in severity during the day.

- An additional disturbance in cognition (memory deficit, disorientation, language. visuospatial ability, or perception).

- The disturbances in Criteria A and C are not better explained by another pre-existing established or evolving neurocognitive disorder and do not occur in a severely reduced level of arousal, such as coma.

- There is evidence from the history, physical examination, or laboratory findings that the disturbance is a direct physiological consequence of another medical condition, substance intoxication or withdrawal (due to a drug of abuse or to a medication), or exposure to a toxin, or is due to multiple etiologies.

There are many assessment tools for delirium that have been validated for a variety of patient populations and hospital locations, including postoperatively on the ward or in the intensive care unit.

These include:

- Confusion Assessment Method (CAM)

- Delirium Symptom Interview (DSI)

- Confusion Assessment Method for the intensive care unit (CAM-ICU) See Figure. The Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU).

- Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist (ICDSC)

CAM and variations of CAM are most commonly used. The CAM-ICU and 3D-CAM are brief versions of CAM that perform moment in time assessments for delirium. The Brief Confusion Assessment Method (bCAM) has been validated in the non-ICU setting. The CAM-ICU is validated for intubated patients on mechanical ventilation. See figure 1.

The Delirium Detection Scale (DDS) and the Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale (MDAS) can assess the severity of delirium.

Treatment / Management

Nonpharmacological followed by pharmacologic interventions should be employed early in the course of delirium to mitigate the risk of long-term adverse sequelae. Nonpharmacological interventions have been tried and have proven to be effective. Notable examples are the Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP) and modified HELP. These programs use multidisciplinary teams that work on reorienting the patient, socialization, daily visits from the family, feeding and nutrition balance, managing sleep-wake cycles, noise reduction, providing sensory aids and early mobilization. Using 3 protocols administered daily; i.e., orienting communication, oral and nutritional assistance, and early mobilization, Chen et al. demonstrated a significant reduction in the incidence of delirium in the intervention group.[10](A1)

The ABCDEF bundle used in the ICU has also been associated with improved brain function outcomes.[11]

- A: Assess and manage pain

- B: Daily awakening and breathing trials

- C: Choice of sedation, light sedation, and avoidance of benzodiazepines

- D: Routine delirium assessment, non-pharmacologic intervention, and judicious use of medications to treat delirium

- E: Early mobility

- F: Family involvement

Hayhurst et al. showed that patients receiving a daily goal-directed mobility program had more days alive and free of delirium, had shorter lengths of hospital stay, were more functionally independent at discharge and were more likely to discharge to home.[12](A1)

To institute prevention strategies, early intervention, and treatment, patients should be evaluated for their risk of POD. In the PACU, reorientation should be started immediately, for example, saying the patient name, current location, type of surgery and surgeon's name. Physical factors such as a distended bladder, hypoventilation, uncomfortable patient positioning, and pain should be addressed promptly.

Several pharmacologic agents have been used to prevent and treat delirium in a high-risk population. Continued delirium should be dealt with aggressively by reversing continued effects of anesthetic agents. Flumazenil (0.2-mg increments), naloxone (0.04-mg increments), and physostigmine because it crosses the blood-brain barrier (1- to 2-mg increments), can reverse the effects of benzodiazepines, opioids, and muscle relaxants. Haldol, which is often used for acute management of delirium, shortens the severity of delirium episodes but does not change the incidence and is also not effective for prophylaxis in high-risk elderly populations.[7] Dexmedetomidine has emerged as a useful adjunct to general anesthesia. Intraoperative infusion of dexmedetomidine was shown to reduce the incidence of POD in high-risk elderly population. Its use in children and in ICU patients has been shown to decrease the incidence of emergence agitation, nausea and vomiting, and postoperative pain. However, its optimal intraoperative dose, infusion or boluses, has not been established.[3][4] Dexmedetomidine was also found to accelerate resolution of delirium, use of fewer antipsychotics and earlier extubation in patients in the ICU in whom agitated delirium prevented extubation.[13] In another study, patients receiving dexmedetomidine had their delirium resolve faster, had less oversedation, less need for noninvasive ventilation and had shorter ICU stay compared to those on haloperidol.[14](A1)

Drugs that increase acetylcholinesterase availability, antipsychotic drugs such as haloperidol have shown no benefit over placebo for the treatment of delirium. Since benzodiazepine sedation has been strongly tied to delirium, propofol and dexmedetomidine have become the mainstay of ICU sedation. Djaiani et al. demonstrated that patients receiving dexmedetomidine had less incidence of and shorter duration of delirium compared to those receiving propofol.[15](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

- Hypoxia

- Hypercarbia

- Hypoglycemia

- Hypothermia

- Stroke

- Seizure

- Central cholinergic syndrome

- Acidemia

- Electrolyte disturbances

- micronutrients and vitamin deficiencies

The patient’s vitals should be checked promptly, and arterial blood gases with blood glucose levels checked while performing a complete physical exam. This would estimate hemoglobin, electrolytes, and blood glucose values. If signs of new focal neurologic deficits are present, a computed tomographic scan of the head should be strongly considered. An individualized panel of lab tests might be requested according to the specific clinical vignette. For instance, a previous history of alcohol abuse might result in thiamine deficiency. In the setting of an abnormal liver function test, along with compatible physical examination, further diagnostic steps are required. Increased carbohydrate metabolites, lactate, pyruvate, and decreased blood thiamine levels are confirmatory. [16]

Treatment Planning

Perioperative suggestions to reduce delirium and brain dysfunction include:

- Avoiding medications that trigger deliria such as anticholinergic medications, benzodiazepines, and meperidine.

- Using light sedation whenever possible and safe

- Ensuring adequate pain control with regional techniques and non-opioid adjuncts

- Using multi-component bundles aimed at reducing delirium such as:

- Attention to hydration and electrolytes

- Early mobility

- Restoring hearing aids and eyeglasses postoperatively

- Using dexmedetomidine for sedation in the postoperative period if sedation is required.

- Treating only those with hyperactive symptoms refractory to non-pharmacologic approaches

Toxicity and Adverse Effect Management

No drug has gained FDA approval for the prevention and treatment of delirium. There are limited data on effective prophylactic agents as well as limited data on effective initial therapies. Haloperidol and atypical antipsychotics (olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone) are commonly used despite limited data on efficacy.

Antipsychotics may cause oversedation, respiratory depression, QT prolongation, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, and hypoactive delirium. Dexmedetomidine requires an infusion and ICU stay.

Prognosis

POD is associated with significantly worse patient outcomes. There is emerging evidence that POD can lead to a higher likelihood of postoperative cognitive dysfunction, prolonged brain dysfunction, early dementia, and acceleration in the cognitive decline of Alzheimer's patients.[17][18] Delirium in the PACU is a sign of further brain dysfunction in the hospital, worse cognition at the time of discharge, and increased likelihood of being admitted at a nursing or rehabilitation facility as opposed to going home.[19] Most studies have shown an association between delirium and increased risk of death.[20]

Complications

Patients with postoperative delirium may be at a higher risk of aspiration, especially in emergency surgery where nil per os (NPO) guidelines were not followed.[21] POD is associated with a prolonged hospital stay and increased health care costs, increased risk of institutionalization after discharge and increased risk of disability.[7]

Consultations

Early mobilization, attention to hydration, supplemental oxygen, excellent pain control, reviewing medication administration, prevention, and management of medical complications and geriatrics consultations in high-risk patients have been successful at decreasing delirium rates.[22]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Sleep enhancement, extra nutrition, vision and hearing protocols, and staff education have also been shown to decrease delirium rates.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Multi-component prevention programs have been shown to reduce the incidence of delirium across medical and surgical patients by approximately 30%. It is important to adopt an interprofessional approach to managing patients at risk of developing POD. Reorienting the patient, calming the patient while looking for obvious and nonobvious precipitating factors in the post-operative period is important. Successful implementation of an interprofessional programs, such as HELP and modified HELP and ABCDEF bundle at various hospitals, has shown encouraging results.[23][24]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Evered L, Silbert B, Knopman DS, Scott DA, DeKosky ST, Rasmussen LS, Oh ES, Crosby G, Berger M, Eckenhoff RG, Nomenclature Consensus Working Group. Recommendations for the Nomenclature of Cognitive Change Associated with Anaesthesia and Surgery-20181. Journal of Alzheimer's disease : JAD. 2018:66(1):1-10. doi: 10.3233/JAD-189004. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30347621]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOh ST, Park JY. Postoperative delirium. Korean journal of anesthesiology. 2019 Feb:72(1):4-12. doi: 10.4097/kja.d.18.00073.1. Epub 2018 Aug 24 [PubMed PMID: 30139213]

Vasilevskis EE, Han JH, Hughes CG, Ely EW. Epidemiology and risk factors for delirium across hospital settings. Best practice & research. Clinical anaesthesiology. 2012 Sep:26(3):277-87. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2012.07.003. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23040281]

Moller JT, Cluitmans P, Rasmussen LS, Houx P, Rasmussen H, Canet J, Rabbitt P, Jolles J, Larsen K, Hanning CD, Langeron O, Johnson T, Lauven PM, Kristensen PA, Biedler A, van Beem H, Fraidakis O, Silverstein JH, Beneken JE, Gravenstein JS. Long-term postoperative cognitive dysfunction in the elderly ISPOCD1 study. ISPOCD investigators. International Study of Post-Operative Cognitive Dysfunction. Lancet (London, England). 1998 Mar 21:351(9106):857-61 [PubMed PMID: 9525362]

Kowark A, Adam C, Ahrens J, Bajbouj M, Bollheimer C, Borowski M, Dodel R, Dolch M, Hachenberg T, Henzler D, Hildebrand F, Hilgers RD, Hoeft A, Isfort S, Kienbaum P, Knobe M, Knuefermann P, Kranke P, Laufenberg-Feldmann R, Nau C, Neuman MD, Olotu C, Rex C, Rossaint R, Sanders RD, Schmidt R, Schneider F, Siebert H, Skorning M, Spies C, Vicent O, Wappler F, Wirtz DC, Wittmann M, Zacharowski K, Zarbock A, Coburn M, iHOPE study group. Improve hip fracture outcome in the elderly patient (iHOPE): a study protocol for a pragmatic, multicentre randomised controlled trial to test the efficacy of spinal versus general anaesthesia. BMJ open. 2018 Oct 18:8(10):e023609. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023609. Epub 2018 Oct 18 [PubMed PMID: 30341135]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMaldonado JR. Pathoetiological model of delirium: a comprehensive understanding of the neurobiology of delirium and an evidence-based approach to prevention and treatment. Critical care clinics. 2008 Oct:24(4):789-856, ix. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2008.06.004. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18929943]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMaldonado JR. Delirium in the acute care setting: characteristics, diagnosis and treatment. Critical care clinics. 2008 Oct:24(4):657-722, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2008.05.008. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18929939]

Morandi A, Pandharipande P, Trabucchi M, Rozzini R, Mistraletti G, Trompeo AC, Gregoretti C, Gattinoni L, Ranieri MV, Brochard L, Annane D, Putensen C, Guenther U, Fuentes P, Tobar E, Anzueto AR, Esteban A, Skrobik Y, Salluh JI, Soares M, Granja C, Stubhaug A, de Rooij SE, Ely EW. Understanding international differences in terminology for delirium and other types of acute brain dysfunction in critically ill patients. Intensive care medicine. 2008 Oct:34(10):1907-15. doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1177-6. Epub 2008 Jun 18 [PubMed PMID: 18563387]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSessler CN, Gosnell MS, Grap MJ, Brophy GM, O'Neal PV, Keane KA, Tesoro EP, Elswick RK. The Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale: validity and reliability in adult intensive care unit patients. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2002 Nov 15:166(10):1338-44 [PubMed PMID: 12421743]

Chen CC, Li HC, Liang JT, Lai IR, Purnomo JDT, Yang YT, Lin BR, Huang J, Yang CY, Tien YW, Chen CN, Lin MT, Huang GH, Inouye SK. Effect of a Modified Hospital Elder Life Program on Delirium and Length of Hospital Stay in Patients Undergoing Abdominal Surgery: A Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA surgery. 2017 Sep 1:152(9):827-834. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.1083. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28538964]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHayhurst CJ, Pandharipande PP, Hughes CG. Intensive Care Unit Delirium: A Review of Diagnosis, Prevention, and Treatment. Anesthesiology. 2016 Dec:125(6):1229-1241 [PubMed PMID: 27748656]

Schaller SJ, Anstey M, Blobner M, Edrich T, Grabitz SD, Gradwohl-Matis I, Heim M, Houle T, Kurth T, Latronico N, Lee J, Meyer MJ, Peponis T, Talmor D, Velmahos GC, Waak K, Walz JM, Zafonte R, Eikermann M, International Early SOMS-guided Mobilization Research Initiative. Early, goal-directed mobilisation in the surgical intensive care unit: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet (London, England). 2016 Oct 1:388(10052):1377-1388. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31637-3. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27707496]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceReade MC, Eastwood GM, Bellomo R, Bailey M, Bersten A, Cheung B, Davies A, Delaney A, Ghosh A, van Haren F, Harley N, Knight D, McGuiness S, Mulder J, O'Donoghue S, Simpson N, Young P, DahLIA Investigators, Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society Clinical Trials Group. Effect of Dexmedetomidine Added to Standard Care on Ventilator-Free Time in Patients With Agitated Delirium: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016 Apr 12:315(14):1460-8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.2707. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26975647]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCarrasco G, Baeza N, Cabré L, Portillo E, Gimeno G, Manzanedo D, Calizaya M. Dexmedetomidine for the Treatment of Hyperactive Delirium Refractory to Haloperidol in Nonintubated ICU Patients: A Nonrandomized Controlled Trial. Critical care medicine. 2016 Jul:44(7):1295-306. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001622. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26925523]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDjaiani G, Silverton N, Fedorko L, Carroll J, Styra R, Rao V, Katznelson R. Dexmedetomidine versus Propofol Sedation Reduces Delirium after Cardiac Surgery: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Anesthesiology. 2016 Feb:124(2):362-8. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000951. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26575144]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceOsiezagha K, Ali S, Freeman C, Barker NC, Jabeen S, Maitra S, Olagbemiro Y, Richie W, Bailey RK. Thiamine deficiency and delirium. Innovations in clinical neuroscience. 2013 Apr:10(4):26-32 [PubMed PMID: 23696956]

Whitlock EL, Vannucci A, Avidan MS. Postoperative delirium. Minerva anestesiologica. 2011 Apr:77(4):448-56 [PubMed PMID: 21483389]

Inouye SK, Marcantonio ER, Kosar CM, Tommet D, Schmitt EM, Travison TG, Saczynski JS, Ngo LH, Alsop DC, Jones RN. The short-term and long-term relationship between delirium and cognitive trajectory in older surgical patients. Alzheimer's & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer's Association. 2016 Jul:12(7):766-75. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.03.005. Epub 2016 Apr 18 [PubMed PMID: 27103261]

Neufeld KJ, Leoutsakos JM, Sieber FE, Wanamaker BL, Gibson Chambers JJ, Rao V, Schretlen DJ, Needham DM. Outcomes of early delirium diagnosis after general anesthesia in the elderly. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2013 Aug:117(2):471-8. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182973650. Epub 2013 Jun 11 [PubMed PMID: 23757476]

Hamilton GM, Wheeler K, Di Michele J, Lalu MM, McIsaac DI. A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Examining the Impact of Incident Postoperative Delirium on Mortality. Anesthesiology. 2017 Jul:127(1):78-88. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001660. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28459734]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRaats JW, van Eijsden WA, Crolla RM, Steyerberg EW, van der Laan L. Risk Factors and Outcomes for Postoperative Delirium after Major Surgery in Elderly Patients. PloS one. 2015:10(8):e0136071. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136071. Epub 2015 Aug 20 [PubMed PMID: 26291459]

Reston JT, Schoelles KM. In-facility delirium prevention programs as a patient safety strategy: a systematic review. Annals of internal medicine. 2013 Mar 5:158(5 Pt 2):375-80. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-5-201303051-00003. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23460093]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceInouye SK, Bogardus ST Jr, Baker DI, Leo-Summers L, Cooney LM Jr. The Hospital Elder Life Program: a model of care to prevent cognitive and functional decline in older hospitalized patients. Hospital Elder Life Program. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2000 Dec:48(12):1697-706 [PubMed PMID: 11129764]

Inouye SK, Baker DI, Fugal P, Bradley EH, HELP Dissemination Project. Dissemination of the hospital elder life program: implementation, adaptation, and successes. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2006 Oct:54(10):1492-9 [PubMed PMID: 17038065]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence