Introduction

Prader-Willi syndrome is a rare, complex genetic condition affecting the metabolic, endocrine, and neurologic systems. It stands out as the predominant syndromic manifestation of obesity. Patients with Prader-Willi syndrome exhibit behavioral, developmental, and intellectual difficulties characterized by severe hypotonia and feeding difficulties in the first years of life. Global developmental delay, hyperphagia, and the onset of obesity manifest around the age of 3. Individuals with Prader-Willi syndrome display distinctive facial features, strabismus, and musculoskeletal abnormalities.

Many patients with Prader-Willi syndrome have short stature due to growth hormone deficiency (GHD). Additionally, they face hypothalamic dysfunction, contributing to various endocrinopathies, including hypogonadism, hypothyroidism, central adrenal insufficiency, and reduced bone mineral density. Continuous monitoring by an endocrinologist is crucial for these patients throughout their lifespan.[1]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Prader-Willi syndrome results from the absence of gene expression of the paternally inherited genes on the 15q11.2-q13 chromosome. Approximately 70% of cases result from errors in genomic imprinting due to a paternal deletion, while maternal uniparental disomy is responsible for about 25% of cases. Fewer cases stem from defects in the imprinting center, such as microdeletions or epimutations on chromosome 15.[1][2]

While most occurrences of Prader-Willi syndrome are sporadic, familial instances may occur when paternal genes carry a microdeletion in the imprinting center inherited from the paternal grandmother. Prader-Willi syndrome was the first genetic disorder identified to be caused by genomic imprinting, where the expression of the gene depends on the parental sex donating the affected gene.

Epidemiology

Prader-Willi syndrome has a prevalence of 1 in every 20,000 to 30,000 births.[3]. Worldwide, around 400,000 individuals are affected by Prader-Willi syndrome, with 20,000 residing in the United States.[2] It stands as the most prevalent genetic cause of life-threatening obesity.[2] Both females and males are equally affected, with no discernible differences noted among races and ethnicities.[4]

Pathophysiology

During birth, individuals with Prader-Willi syndrome exhibit growth parameters—including weight, length, and body mass index—15% to 20% smaller than their unaffected siblings, indicating decreased prenatal growth. Observable prenatal hypotonia is evident through decreased fetal movement and abnormal positions during delivery, contributing to a higher incidence of assisted births and Cesarean section deliveries.[5]

History and Physical

The clinical manifestations of Prader-Willi syndrome vary across different age groups, constituting a range of features. Symptoms may manifest at birth and tend to become more apparent over time.

Hypotonia is a common feature in nearly all infants with Prader-Willi syndrome. This is accompanied by a poor sucking reflex, resulting in feeding difficulties, diminished muscle mass and strength, poor weight gain early in life, and the need for specialized feeding devices or extended periods of enteral nutrition. Prenatally, there is reduced fetal movement, and the onset of "quickening," the perception of movement by the pregnant mother, occurs later in the pregnancy.[2][5]

Prader-Willi syndrome is characterized by dysmorphic facial features, including a narrow frontal diameter, almond-shaped palpebral fissures, strabismus, a slender nasal bridge, a thin upper vermillion border with downturned mouth corners, and enamel hypoplasia. During physical examination, small hands and feet are frequently observed, although these characteristics may not be evident at birth but develop later.[2][5]

Developmental delays and behavioral issues are also common. Motor developmental delay is expected, with the attainment of early milestones typically occurring at about half the usual pace.[5] The median age of independent walking is 27 months.[6] Language impairment commonly occurs, and intellectual and learning disabilities typically manifest by school age.[7] Behavioral problems, such as anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, temper outbursts, and self-inflicted injuries, are prevalent in almost all individuals with Prader-Willi syndrome.[4]

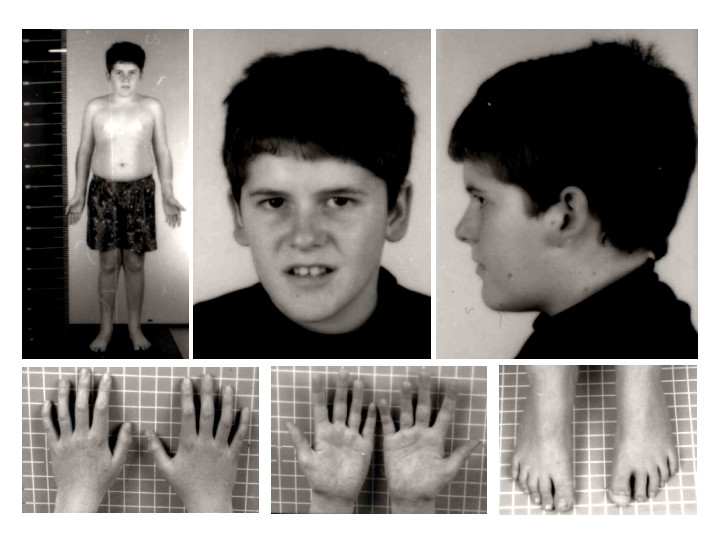

GHD is the most frequently reported endocrinopathy in patients with Prader-Willi syndrome. Short stature may present in early childhood and is seen by the second decade of life, accompanied by accelerated weight gain and truncal obesity (see Image. Prader-Willi Syndrome Phenotype). Although the pathogenesis is unclear, insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) is deficient or subnormal in nearly all patients with Prader-Willi syndrome. The growth hormone secretion test and the 24-hour spontaneous secretion of growth hormone show impairment.[1][5] Patients display short stature and growth deceleration, failing to achieve the typical puberty growth spurt.[8]

The progression leading to the hallmark hyperphagia and obesity in Prader-Willi syndrome can be described in 4 phases (see Table. Phases of Prader-Willi Syndrome)

Table 1. Phases of Prader-Willi Syndrome

| Phase | Presentation | Age |

| 1a | Infants are hypotonic and feed poorly with slow weight gain | Birth to 9 to 15 months |

| 1b | Steady growth with a typical rate of weight gain | 9 to 24 months |

| 2a | Weight gain without significantly increasing caloric intake or appetite | 2 to 4.5 years |

| 2b | Frank hyperphagia and heightened interest in food | 4.5 years to 8 years [9] |

| 3 | Increased hyperphagia, food-seeking behaviors, lack satiety | 8 years to adult |

| 4 | Insatiable appetite resolves | Adulthood [2][5] |

In Prader-Willi syndrome, central obesity is typical, leading to significant complications and increased morbidity and mortality.[5] In adults, hyperphagia can result in choking, which can even cause sudden death.[10] Food-seeking behaviors include binge eating and consuming garbage and non-food items. The biological mechanism for this impaired satiety is unclear. In some studies, ghrelin levels are elevated in patients with Prader-Willi syndrome compared to weight and age-matched controls.[11][12]

Hypogonadism is prevalent in patients with Prader-Willi syndrome. Almost all affected males experience cryptorchidism, often necessitating orchiopexy. Male infants also display scrotal hypoplasia, while females may exhibit hypoplasia or absence of the labia minora and clitoral hypoplasia.[13] Penile size is initially reported as average at birth but later falls 2 standard deviations below the normal curve. As a result of smaller penile size and increased fat pad over the pubic area, standing urination can pose challenges, and a short course of testosterone may aid in potty training. Upon reaching puberty at the typical age, there is an increase in testosterone levels, but they remain abnormally low. Puberty arrest is evident at Tanner stage 3 in sexual maturity rating, characterized by testicular failure and a small testicular size persisting into adulthood.

Females with Prader-Willi syndrome are born with external genitalia hypoplasia. While puberty usually begins at the typical age, breast development may be significantly delayed. Spontaneous menarche is rare in Prader-Willi syndrome, typically occurring around age 20. Estrogen and luteinizing hormone levels are low to normal, while follicular stimulating hormone levels are normal to high, indicating central and primary defects.

Both males and females with Prader-Willi syndrome are considered infertile, and there is a notable incidence of premature adrenarche in both genders. Approximately 14% to 30% of cases are associated with advanced bone age, potentially influenced by the presence of obesity.[1]

Additional manifestations of Prader-Willi syndrome include sleep disorders, thick viscous saliva, high pain threshold, decreased vomiting, epilepsy, temperature instability, scoliosis/kyphosis, and osteoporosis. Skin, iris, and hair hypopigmentation relative to that expected for family background occurs in 30% to 50% of patients with Prader-Willi syndrome.[14] Obesity associated with Prader-Willi syndrome leads to many predictable complications, including cardiovascular disease, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), dyslipidemia, diabetes, sleep apnea, and respiratory failure.

Evaluation

When clinical features suggest Prader-Willi syndrome, the recommended diagnostic approach involves molecular testing with DNA methylation analysis, which detects over 99% of cases.[15] A positive result prompts further testing to identify the presence of a deletion, maternal disomy, or imprinting defect. Chromosome analysis using fluorescence in situ hybridization can identify the 15q11-q13 deletion, while chromosomal microarray can reveal maternal disomy.[2][16] In resource-rich countries, diagnosis often occurs early, around 2 months of age. However, confirmation may be delayed until around 4 years of age, especially in tertiary referral centers.[7]

Additional studies tailored to individual patient needs include:

- Thyroid function tests to determine the presence of hypothyroidism, especially when considering growth hormone treatment [2]

- Liver function tests, serum IGF-1, and insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 to evaluate possible GHD[2]

- Fasting glucose level, hemoglobin A1c, and oral glucose tolerance test if diabetes is suspected

- Polysomnography (sleep study) to diagnose sleep disorders

- Dual x-ray absorptiometry (DXA scan) to assess bone mineralization and composition[2]

Treatment / Management

Managing patients with Prader-Willi syndrome depends upon the affected individual's age and involves evaluating and monitoring various organ systems. Infants with Prader-Willi syndrome exhibit muscular hypotonia, difficulty feeding, and inadequate weight gain, often necessitating a feeding team evaluation for specialized feeding techniques and the incorporation of high-calorie supplements or formulas. As hyperphagia emerges in childhood, restricting food intake is critical. Most patients have reduced energy needs, requiring approximately 70% of the calories compared to their age-matched peers without Prader-Willi syndrome. While an ideal calorie-restricted diet may lack sufficient vitamins and minerals, supplements should be prescribed to meet daily requirements, with caution against gummy vitamins due to their high caloric content and the risk of overdose, given their candy-like taste.

Caregivers implement physical barriers, such as locking food cupboards and refrigerators and close supervision, to enforce food restrictions. Individuals with hyperphagia may neglect thoroughly chewing food, elevating the risk of choking and thus emphasizing the critical need for caregiver training in the Heimlich maneuver. In cases of severe obesity in older children and adults, treatment with weight loss medications and bariatric surgery can be considered.

Hypotonia and motor delays in individuals with Prader-Willi syndrome can be effectively addressed through physical and occupational therapy. Additionally, early treatment with recombinant human growth hormone (rhGH) improves strength, physical function, and muscle development in pediatric patients with Prader-Willi syndrome. Formal growth hormone testing is not a prerequisite, and treatment with rhGH in children can be initiated upon diagnosis, preferably before the first birthday.[7][17] Continuous treatment with rhGH during adolescence is recommended to maximize linear growth.

Adults, particularly those with persistent GHD, may also benefit from rhGH treatment. Close height monitoring is essential for all children and teenagers with Prader-Willi syndrome. While the disadvantage of rhGH is the need for daily or weekly injections, the treatment is associated with improved linear growth, reduced obesity, and enhanced bone density and motor function. Patients treated with rhGH during childhood are likelier to approach their predicted final adult height.[8]

Cryptorchidism is observed in most young boys with Prader-Willi syndrome. While human chorionic gonadotropin treatment may be effective in some cases, the majority require orchiopexy.[1] Consultation with an endocrinologist is recommended at puberty since hormonal replacement may be indicated for delayed puberty. Treatment with testosterone is indicated for boys with delayed puberty, while girls receive estrogen replacement in the form of transdermal patches until the onset of menarche.[1][5]

Most patients with Prader-Willi syndrome experience behavior or psychiatric diagnoses, with about a quarter of children meeting the diagnostic criteria for autism spectrum disorder.[18] Adolescents and adults with mood disorders or psychoses may require medication and therapy.(A1)

Behavioral strategies assist patients in understanding rules, schedules, expectations, and verbal cues, minimizing symptoms of compulsion and aggression.[7] Skin picking is frequent, and a study demonstrated the benefits of treatment with oral guanfacine.[19] Cognitive impairment is prevalent in many individuals, and adults may exhibit accelerated cognitive decline with age. It is recommended that schoolchildren have an individualized educational plan (IEP), while adults often thrive in a supervised vocational setting.(B2)

Reduced bone mineral density is typical, and patients should undergo evaluation through DXA scans every 2 to 3 years, starting from the age of 5 years. Scoliosis is also common, and it is advisable to monitor pediatric patients during routine visits, referring them for orthopedic evaluation when indicated.

Hypothyroidism may also manifest, and routine testing is recommended to commence within the first year.[20] Type 2 diabetes can emerge as a complication of severe obesity, and screening should be conducted if indicated. Sleep-disordered breathing, a common complication of obesity, affects most children and young adults. Individuals experiencing daytime sleepiness and behavior problems should be evaluated for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and in some cases, surgical intervention with tonsillectomy or adenotonsillectomy may be necessary.

Differential Diagnosis

Several disorders exhibit clinical features like Prader-Willi syndrome and should be considered when diagnosing a patient with Prader-Willi syndrome. Neonatal hypotonia can also result from neuropathies and myopathies like spinal myotonic dystrophy, characterized by poor respiratory effort early in life.[5] Patients with Prader-Willi-like syndrome present with features resembling Prader-Willi syndrome but differ genetically. Notable clinical features shared by both include hypotonia, short stature, obesity, and developmental delays.[21]

Children with craniopharyngioma, a rare tumor, may exhibit features that overlap with Prader-Willi syndrome as a result of the treatment's impact on the hypothalamus.[5] The distinct presentation of Prader-Willi syndrome involves a gradual progression from hypotonia with poor feeding and slow weight gain to hyperphagia, followed by severe obesity, setting it apart from other diseases.

Prognosis

The prognosis for patients with Prader-Willi syndrome varies, influenced by the timing of diagnosis and the extent of complications. Initiating treatment early and preventing severe obesity increases the likelihood of patients attaining an average lifespan. However, due to intellectual disabilities, most affected individuals require supportive services and are less likely to lead fully independent lives as adults.

Complications such as obesity, diabetes, and heart failure shorten life expectancy in Prader-Willi syndrome. Death frequently occurs in the fourth decade when comorbidities are inadequately controlled. However, individuals with Prader-Willi syndrome have the potential to reach the seventh decade if their weight is curbed.[2][22]

Complications

Numerous Prader-Willi syndrome complications result from severe obesity but may also be related to musculoskeletal, neurologic, behavioral, and developmental conditions affecting multiple organ systems.

- Respiratory: OSA, hypoventilation, aspiration pneumonia, and obesity-related respiratory failure [23]

- Cardiovascular: Hypertension and right-sided heart failure

- Gastrointestinal: Gastroparesis, delayed gastric emptying, NAFLD, decreased salivary secretions, increased ghrelin secretion by the stomach, and gastric perforation or obstruction related to binge eating

- Musculoskeletal: Osteoporosis, fractures, scoliosis, kyphosis, and hip dysplasia [24]

- Skin: Stasis ulcers and cellulitis

- Behavioral: Tantrums, outbursts, self-injury, food stealing and hoarding, delayed cognitive development, intellectual disabilities, and learning disabilities

- Neurologic: Hypotonia, temperature instability, and seizures [2]

- Endocrine: Short stature, GHD, central adrenal insufficiency, hypothyroidism, hypogonadism, and type 2 diabetes [25]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Clinicians caring for children should maintain a high index of suspicion and assess infants displaying hypotonia, poor sucking, slow weight gain, or cryptorchidism for Prader-Willi syndrome. Early diagnosis and intervention can effectively address issues during infancy, and family caregivers should receive education about the developmental course of the condition. Children with Prader-Willi syndrome require meticulous dietary intervention to prevent severe obesity, along with comprehensive medical and educational services from a multidisciplinary approach.

Pearls and Other Issues

Key facts to keep in mind about Prader-Willi syndrome include:

- Prader-Willi syndrome is a genetic disorder caused by the lack of expression of paternally inherited genes on chromosome 15q11-13, often due to a deletion in this region, maternal uniparental disomy (both copies from the mother), or imprinting defects.

- Prader-Willi syndrome is characterized by neonatal hypotonia, feeding difficulties, developmental delays, and later onset of hyperphagia leading to obesity. Distinct facial features may be present, such as almond-shaped eyes and a thin upper lip.

- DNA methylation analysis is a key diagnostic test, detecting abnormalities in over 99% of cases.

- There are 4 distinct phases, including hypotonia and poor feeding in infancy, followed by excessive eating and obesity starting around age 3. Behavioral issues, including food-seeking behaviors, are common.

- Individuals with Prader-Willi syndrome are typically infertile. Both males and females may exhibit premature adrenarche, and advanced bone age is correlated with obesity.

- Central obesity is a characteristic feature that leads to significant health complications and increased morbidity and mortality.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Prader-Willi syndrome is a complex genetic disorder resulting from a defect on chromosome 15. Healthcare practitioners should suspect this diagnosis when an infant demonstrates significant hypotonia, difficulty feeding, and slow weight gain, followed by hyperphagia that results in severe obesity. Upon diagnosis, it is crucial to incorporate an interprofessional team, including consultations with genetics, endocrinology, and developmental medicine, to monitor the progression of the patient's symptoms and prevent and treat complications. Parents should undergo genetic counseling to estimate recurrence risk in future pregnancies.

A nutritionist or registered dietitian can provide essential dietary advice for infants to facilitate appropriate weight gain and mitigate the risk of severe obesity and its complications. Infants may require evaluation by a feeding team to enable appropriate weight gain during the first year. Children under 3 should participate in Early Intervention to assess and treat global developmental delays. Older pediatric patients require an IEP at school that may include speech, physical, and occupational therapy.

A board-certified clinical pharmacist assists with dosing hormonal replacement medication when indicated. Nursing staff monitor and document the patient's response to treatment at each visit, charting growth and laboratory results to allow the clinical team to modify the regimen as needed. Nurses support families and coordinate care for individuals with Prader-Willi syndrome with specialized nutritional, behavioral, and educational needs. A mental health nurse is a valuable interprofessional team member, assisting affected individuals and their caregivers. Psychiatrists and psychiatric nurse practitioners prescribe medication for mood disorders and psychoses. Visiting nurses conduct home visits and help families with practical techniques to manage food-seeking behaviors safely. Patients with orthopedic problems benefit from physical and occupational therapy, enabling them to perform activities of daily living. This interprofessional team approach is necessary to optimize clinical outcomes, reduce morbidity, and improve the quality of life and longevity of patients with Prader-Willi syndrome.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Prader-Willi Syndrome Phenotype. The child is 15 years of age with the Prader-Willi phenotype. Note the absence of typical Prader-Willi syndrome facial features. Mild truncal obesity can be noted.

Contributed by Wikimedia Commons, Schüle B et al (CC by 2.0) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

References

Heksch R, Kamboj M, Anglin K, Obrynba K. Review of Prader-Willi syndrome: the endocrine approach. Translational pediatrics. 2017 Oct:6(4):274-285. doi: 10.21037/tp.2017.09.04. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29184809]

Butler MG, Manzardo AM, Forster JL. Prader-Willi Syndrome: Clinical Genetics and Diagnostic Aspects with Treatment Approaches. Current pediatric reviews. 2016:12(2):136-66 [PubMed PMID: 26592417]

Pacoricona Alfaro DL, Lemoine P, Ehlinger V, Molinas C, Diene G, Valette M, Pinto G, Coupaye M, Poitou-Bernert C, Thuilleaux D, Arnaud C, Tauber M. Causes of death in Prader-Willi syndrome: lessons from 11 years' experience of a national reference center. Orphanet journal of rare diseases. 2019 Nov 4:14(1):238. doi: 10.1186/s13023-019-1214-2. Epub 2019 Nov 4 [PubMed PMID: 31684997]

Bohonowych J, Miller J, McCandless SE, Strong TV. The Global Prader-Willi Syndrome Registry: Development, Launch, and Early Demographics. Genes. 2019 Sep 14:10(9):. doi: 10.3390/genes10090713. Epub 2019 Sep 14 [PubMed PMID: 31540108]

Cassidy SB, Schwartz S, Miller JL, Driscoll DJ. Prader-Willi syndrome. Genetics in medicine : official journal of the American College of Medical Genetics. 2012 Jan:14(1):10-26. doi: 10.1038/gim.0b013e31822bead0. Epub 2011 Sep 26 [PubMed PMID: 22237428]

Butler MG. Prader-Willi syndrome: current understanding of cause and diagnosis. American journal of medical genetics. 1990 Mar:35(3):319-32 [PubMed PMID: 2309779]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePassone CBG, Pasqualucci PL, Franco RR, Ito SS, Mattar LBF, Koiffmann CP, Soster LA, Carneiro JDA, Cabral Menezes-Filho H, Damiani D. PRADER-WILLI SYNDROME: WHAT IS THE GENERAL PEDIATRICIAN SUPPOSED TO DO? - A REVIEW. Revista paulista de pediatria : orgao oficial da Sociedade de Pediatria de Sao Paulo. 2018 Jul-Sep:36(3):345-352. doi: 10.1590/1984-0462/;2018;36;3;00003. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30365815]

Angulo MA, Butler MG, Cataletto ME. Prader-Willi syndrome: a review of clinical, genetic, and endocrine findings. Journal of endocrinological investigation. 2015 Dec:38(12):1249-63. doi: 10.1007/s40618-015-0312-9. Epub 2015 Jun 11 [PubMed PMID: 26062517]

Miller JL, Lynn CH, Driscoll DC, Goldstone AP, Gold JA, Kimonis V, Dykens E, Butler MG, Shuster JJ, Driscoll DJ. Nutritional phases in Prader-Willi syndrome. American journal of medical genetics. Part A. 2011 May:155A(5):1040-9. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33951. Epub 2011 Apr 4 [PubMed PMID: 21465655]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBellis SA, Kuhn I, Adams S, Mullarkey L, Holland A. The consequences of hyperphagia in people with Prader-Willi Syndrome: A systematic review of studies of morbidity and mortality. European journal of medical genetics. 2022 Jan:65(1):104379. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2021.104379. Epub 2021 Nov 5 [PubMed PMID: 34748997]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCummings DE, Clement K, Purnell JQ, Vaisse C, Foster KE, Frayo RS, Schwartz MW, Basdevant A, Weigle DS. Elevated plasma ghrelin levels in Prader Willi syndrome. Nature medicine. 2002 Jul:8(7):643-4 [PubMed PMID: 12091883]

Haqq AM, Farooqi IS, O'Rahilly S, Stadler DD, Rosenfeld RG, Pratt KL, LaFranchi SH, Purnell JQ. Serum ghrelin levels are inversely correlated with body mass index, age, and insulin concentrations in normal children and are markedly increased in Prader-Willi syndrome. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2003 Jan:88(1):174-8 [PubMed PMID: 12519848]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceCrinò A, Schiaffini R, Ciampalini P, Spera S, Beccaria L, Benzi F, Bosio L, Corrias A, Gargantini L, Salvatoni A, Tonini G, Trifirò G, Livieri C, Genetic Obesity Study Group of Italian Society of Pediatric endocrinology and diabetology (SIEDP). Hypogonadism and pubertal development in Prader-Willi syndrome. European journal of pediatrics. 2003 May:162(5):327-33 [PubMed PMID: 12692714]

Butler MG. Hypopigmentation: a common feature of Prader-Labhart-Willi syndrome. American journal of human genetics. 1989 Jul:45(1):140-6 [PubMed PMID: 2741944]

Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, Gripp KW, Amemiya A, Driscoll DJ, Miller JL, Cassidy SB. Prader-Willi Syndrome. GeneReviews(®). 1993:(): [PubMed PMID: 20301505]

Strom SP, Hossain WA, Grigorian M, Li M, Fierro J, Scaringe W, Yen HY, Teguh M, Liu J, Gao H, Butler MG. A Streamlined Approach to Prader-Willi and Angelman Syndrome Molecular Diagnostics. Frontiers in genetics. 2021:12():608889. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2021.608889. Epub 2021 May 11 [PubMed PMID: 34046054]

Duis J, van Wattum PJ, Scheimann A, Salehi P, Brokamp E, Fairbrother L, Childers A, Shelton AR, Bingham NC, Shoemaker AH, Miller JL. A multidisciplinary approach to the clinical management of Prader-Willi syndrome. Molecular genetics & genomic medicine. 2019 Mar:7(3):e514. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.514. Epub 2019 Jan 29 [PubMed PMID: 30697974]

Bennett JA, Germani T, Haqq AM, Zwaigenbaum L. Autism spectrum disorder in Prader-Willi syndrome: A systematic review. American journal of medical genetics. Part A. 2015 Dec:167A(12):2936-44. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.37286. Epub 2015 Aug 29 [PubMed PMID: 26331980]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSingh D, Wakimoto Y, Filangieri C, Pinkhasov A, Angulo M. Guanfacine Extended Release for the Reduction of Aggression, Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Symptoms, and Self-Injurious Behavior in Prader-Willi Syndrome-A Retrospective Cohort Study. Journal of child and adolescent psychopharmacology. 2019 May:29(4):313-317. doi: 10.1089/cap.2018.0102. Epub 2019 Feb 6 [PubMed PMID: 30724590]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAlves C, Franco RR. Prader-Willi syndrome: endocrine manifestations and management. Archives of endocrinology and metabolism. 2020 May-Jun:64(3):223-234. doi: 10.20945/2359-3997000000248. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32555988]

Cheon CK. Genetics of Prader-Willi syndrome and Prader-Will-Like syndrome. Annals of pediatric endocrinology & metabolism. 2016 Sep:21(3):126-135 [PubMed PMID: 27777904]

Butler MG, Manzardo AM, Heinemann J, Loker C, Loker J. Causes of death in Prader-Willi syndrome: Prader-Willi Syndrome Association (USA) 40-year mortality survey. Genetics in medicine : official journal of the American College of Medical Genetics. 2017 Jun:19(6):635-642. doi: 10.1038/gim.2016.178. Epub 2016 Nov 17 [PubMed PMID: 27854358]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDuis J, Pullen LC, Picone M, Friedman N, Hawkins S, Sannar E, Pfalzer AC, Shelton AR, Singh D, Zee PC, Glaze DG, Revana A. Diagnosis and management of sleep disorders in Prader-Willi syndrome. Journal of clinical sleep medicine : JCSM : official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. 2022 Jun 1:18(6):1687-1696. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.9938. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35172921]

Greggi T, Martikos K, Lolli F, Bakaloudis G, Di Silvestre M, Cioni A, Bròdano GB, Giacomini S. Treatment of scoliosis in patients affected with Prader-Willi syndrome using various techniques. Scoliosis. 2010 Jun 15:5():11. doi: 10.1186/1748-7161-5-11. Epub 2010 Jun 15 [PubMed PMID: 20550681]

Yang A, Kim J, Cho SY, Jin DK. Prevalence and risk factors for type 2 diabetes mellitus with Prader-Willi syndrome: a single center experience. Orphanet journal of rare diseases. 2017 Aug 30:12(1):146. doi: 10.1186/s13023-017-0702-5. Epub 2017 Aug 30 [PubMed PMID: 28854950]