Pruritic Urticarial Papules and Plaques of Pregnancy

Pruritic Urticarial Papules and Plaques of Pregnancy

Introduction

Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy (PUPPP), also known as polymorphic eruption of pregnancy (PEP) is the most common gestational dermatosis.[1] It is a benign, pruritic, inflammatory skin disorder, characterized by a polymorphous clinical presentation, normal laboratory tests, and negative direct immunofluorescence. PUPPP usually affects primigravidas in their third trimester of pregnancy, less frequently in the immediate postpartum period, and has no tendency for recurrence in subsequent pregnancies. Lawley et al. first described this entity in 1979, based on the initial clinical findings of urticarial papules and plaques, developing within striae distensae.[2] To encompass the later polymorphous features, also described in this condition, the term “polymorphic eruption of pregnancy” has been suggested and is now similarly accepted.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The cause of pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy is still unknown, although various etiological theories have been proposed, including abdominal distension, hormonal changes, placental factors and the role of fetal DNA in skin lesions of patients with PUPPP.[3] In a study of Holms and al. the eruption was thought to have developed in 90% of patients, as a consequence of damage to connective tissue within striae.[4] Therefore suggestions have been that rapid, late stretching of abdominal skin, occurring with a high frequency in multiple pregnancies, may lead to connective tissue damage and that the exposure of antigens within collagen could elicit an allergic-type reaction, resulting in the initial appearance of the eruption in striae. Additionally, there are suggestions that peripheral chimerism (deposition of fetal DNA), which occurs particularly during the third trimester, and favors skin with increased vascularity and damaged collagen, could be subsequently the target of immune reactivity.[5] The mechanism by which lesions become generalized is also unclear. An inflammatory response is thought to be promoted by cross-reactivity to collagen in otherwise normal-appearing skin. An immune tolerance mechanism during subsequent pregnancies might prevent recurrence.[3] High levels of progesterone, especially if multiple gestations and increased progesterone receptor immunoreactivity have been demonstrated in patients with PUPPP [6]. Another hypothesis centers on fibroblast proliferation in the maternal skin, induced by a placental hormonal-type substance.[7]

Epidemiology

The reported incidence of pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy in the literature is 0,5% in single pregnancies, 2.9 to 16% in twin pregnancies and 14 to 17 % in triplet pregnancies.[8][9] It is seen predominantly in primigravidas women and tends not to relapse in later pregnancies. Reports have linked excessive maternal weight gain and increased newborn birth weight in association with PUPPP. Patients affected were interestingly Rh-positive in a study of Ghazeeri and colleagues, and in 89% of them, conception was the product of in vitro fertilization.[10] Relative to fetus gender, a male to female ratio of 2 to 1 has been reported. Usually, there is no family history of this type of eruption and studies revealed, neither an autoimmune diathesis nor a specific HLA type association.[4]

Histopathology

Biopsy specimens from lesional skin reveal nonspecific findings. In early pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy lesions, there is epidermal and upper dermal edema, and occasionally focal mild spongiosis, with a deeper dermal lymphohistiocytic perivascular infiltrate,[11] which may resemble arthropod bite reactions. The lymphocytic infiltrate is often composed of T-helper lymphocytes with an admixture of a variable number of eosinophils and neutrophils. In the resolving stage of PUPPP, there is acanthosis with hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis. Ghazeeri and al. reported epidermal changes commonly seen in the biopsies taken from patients who had lesions with various morphologies including papulovesicular rash, target-like lesions, and eczematous lesions.[10] Direct immunofluorescence of lesional skin is usually negative. Nevertheless, minimal nonspecific granular deposition of IgM, C3 or IgA along the dermal-epidermal junction or blood vessels had also been reported.[8] Indirect immunofluorescence investigations for circulating IgG antibodies shows almost always negative results. But in one study the presence of circulating IgM anti-basement membrane zone, in 5 from 111 cases had been reported.[12]

History and Physical

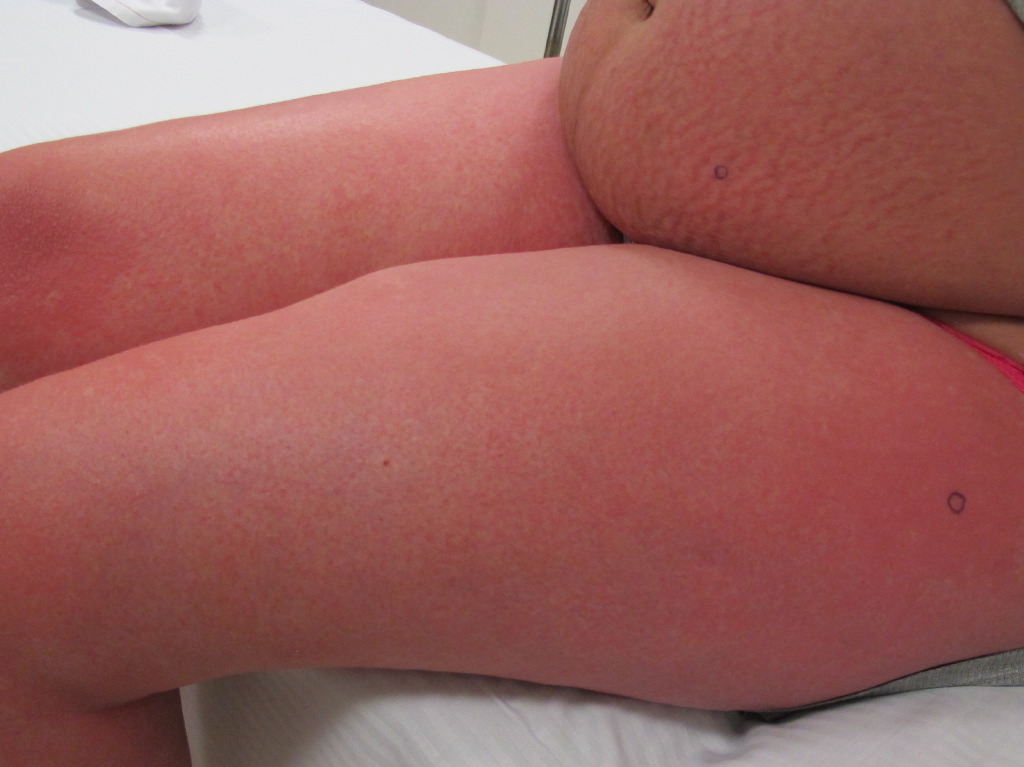

Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy occur most often during the last month of pregnancy and only rarely appear in the postpartum period. The rash consists of itchy small erythematous and edematous papules and plaques usually first start in the stretch marks, typically with periumbilical sparing. The lesions can coalesce to form larger urticarial abdominal plaques often surrounded by blanched halos. The eruption spreads over a matter of days, to the trunk and the extremities, but rarely involves the face, palms, or soles.[1] After that, almost all patients develop more polymorphic features as the disease evolves, including widespread erythema, targetoid lesions, tiny vesicles, and eczematous patches. Mucosal involvement is usually not observed. When PUPPP resolves, typically over an average of 4 weeks spontaneously or with delivery, there is no post-inflammatory pigment change or scarring of the skin. The eruption tends to not recur with subsequent pregnancies.

Evaluation

Usually, routine laboratory tests are within normal limits in patients with PUPPP. Upon consideration of the diagnosis, the degree of discomfort related to pruritus should be evaluated in all cases as the treatment is mainly symptomatic. Additionally, maternal weight and fetus growth should be plotted during the pregnancy course. Generally, PUPPP is not an indication for early delivery.

Treatment / Management

Only symptomatic treatment is usually necessary for patients with PUPPP. The majority of affected ladies achieve satisfactory control with topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines. Further, sedating first-generation antihistamines appear to be safe in pregnancy and can be used as adjunct therapy to provide relief from pruritus. For severe disease with disturbed sleep leading to exhaustion of the mother, a short course of systemic corticosteroids can be helpful. General measures, such as cool, soothing baths, frequent application of emollients and light cotton clothing, offers additional symptomatic relief.[3] Recently, intramuscular injection of autologous whole blood has been suggested as an alternative treatment option in a case of post-partum PUPPP, with both subjective and objective improvement of the symptoms.[13](B3)

Differential Diagnosis

The most important diagnosis to exclude is urticarial pemphigoid gestationis. As the clinical features can overlap, histological and immunological studies are necessary to make the distinction between these two disorders [3]. Although in pemphigoid gestationis, lesions usually have an earlier onset during gestation, and often involve the umbilicus, along with positive immunofluorescence of perilesional skin. In eczema, patients typically have a personal or family history of atopy and the eruption is characterized by pruritic erythematous lesions on flexural areas. Drug eruptions, urticaria, or viral exanthems may also be in the clinical differential diagnosis.

Prognosis

Apart from the discomfort of a pruritic urticarial eruption, maternal prognosis still unaffected. Early delivery is rarely used for relief of intractable pruritus.[14] There are no fetal morbidities, and neonatal skin is usually not affected. Recurrence of the eruption in subsequent pregnancies is unusual, except for multiple-gestation pregnancies. In this case, PUPPP tends to be less severe than the first episode.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy is a skin disorder with an ordinarily benign course, in almost all cases. Nevertheless, close cooperation between dermatologist, obstetrician, labor and delivery nurse and the neonatal pediatrician is necessary in the management of severe cases.[3] In general, patients should understand that PUPPP is a well-recognized condition, usually limited in duration, and does not imply any increased maternal or fetal risk.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Lehrhoff S, Pomeranz MK. Specific dermatoses of pregnancy and their treatment. Dermatologic therapy. 2013 Jul-Aug:26(4):274-84. doi: 10.1111/dth.12078. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23914884]

Lawley TJ, Hertz KC, Wade TR, Ackerman AB, Katz SI. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy. JAMA. 1979 Apr 20:241(16):1696-9 [PubMed PMID: 430731]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAhmadi S, Powell FC. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy: current status. The Australasian journal of dermatology. 2005 May:46(2):53-8; quiz 59 [PubMed PMID: 15842394]

Charles-Holmes R. Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy. Seminars in dermatology. 1989 Mar:8(1):18-22 [PubMed PMID: 2701704]

Aractingi S, Berkane N, Bertheau P, Le Goué C, Dausset J, Uzan S, Carosella ED. Fetal DNA in skin of polymorphic eruptions of pregnancy. Lancet (London, England). 1998 Dec 12:352(9144):1898-901 [PubMed PMID: 9863788]

Campbell DM. Maternal adaptation in twin pregnancy. Seminars in perinatology. 1986 Jan:10(1):14-8 [PubMed PMID: 3532339]

Ingber A, Alcalay J, Sandbank M. Multiple dermal fibroblasts in patients with pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy. A clue to the etiology? Medical hypotheses. 1988 May:26(1):11-2 [PubMed PMID: 3398786]

Rudolph CM, Al-Fares S, Vaughan-Jones SA, Müllegger RR, Kerl H, Black MM. Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy: clinicopathology and potential trigger factors in 181 patients. The British journal of dermatology. 2006 Jan:154(1):54-60 [PubMed PMID: 16403094]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceElling SV, McKenna P, Powell FC. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy in twin and triplet pregnancies. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2000 Sep:14(5):378-81 [PubMed PMID: 11305379]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGhazeeri G, Kibbi AG, Abbas O. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy: epidemiological, clinical, and histopathological study of 18 cases from Lebanon. International journal of dermatology. 2012 Sep:51(9):1047-53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05203.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22909357]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHolmes RC, Jurecka W, Black MM. A comparative histopathological study of polymorphic eruption of pregnancy and herpes gestationis. Clinical and experimental dermatology. 1983 Sep:8(5):523-9 [PubMed PMID: 6641010]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceZurn A, Celebi CR, Bernard P, Didierjean L, Saurat JH. A prospective immunofluorescence study of 111 cases of pruritic dermatoses of pregnancy: IgM anti-basement membrane zone antibodies as a novel finding. The British journal of dermatology. 1992 May:126(5):474-8 [PubMed PMID: 1610688]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKim EH. Pruritic Urticarial Papules and Plaques of Pregnancy Occurring Postpartum Treated with Intramuscular Injection of Autologous Whole Blood. Case reports in dermatology. 2017 Jan-Apr:9(1):151-156. doi: 10.1159/000473874. Epub 2017 Apr 27 [PubMed PMID: 28559815]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBeltrani VP, Beltrani VS. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy: a severe case requiring early delivery for relief of symptoms. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1992 Feb:26(2 Pt 1):266-7 [PubMed PMID: 1552069]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence