Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic proliferative and inflammatory condition of the skin. It is characterized by erythematous plaques covered with silvery scales, particularly over the extensor surfaces, scalp, and lumbosacral region.[1][2][3]

The disorder can also affect the joints and eyes. Psoriasis has no cure and the disease waxes and wanes with flareups. Many patients with psoriasis develop depression as the quality of life is poor. There are several subtypes of psoriasis but the plaque type is the most common and presents on the trunk, extremities, and scalp. Close examination of the plaques usually reveals white silvery scales.

The eye is involved in about 10% of patients, mostly women. In general, the eye is rarely involved alone; it is almost always associated with skin features.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Psoriasis has a prevalence ranging from 0.2% to 4.8%.[4] The exact etiology is unknown, but it is considered to be an autoimmune disease mediated by T lymphocytes. There is an association of HLA antigens seen in many psoriatic patients, particularly in various racial and ethnic groups. Familial occurrence suggests its genetic predisposition. Injury in the form of mechanical, chemical, and radiational trauma induces lesions of psoriasis. Certain drugs like chloroquine, lithium, beta-blockers, steroids, and NSAIDs can worsen psoriasis. Generally, summer improves psoriasis while winter aggravates it. Apart from the above factors infections, psychological stress, alcohol, smoking, obesity, and hypocalcemia are other triggering factors for psoriasis.[5]

Epidemiology

Psoriasis occurs worldwide, and its prevalence varies. In the United States, about 2% of the population is affected. High rates of psoriasis have been reported in the Faroe Islands. The prevalence of psoriasis is low in Japan and may be absent in Aboriginal Australians and Indians from South America.

Psoriasis can present at any age. A bimodal age of onset has been recognized. The mean age of onset for the first presentation of psoriasis can range from 15 to 20 years of age, with a second peak occurring at 55 to 60 years. [6][7]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of psoriasis involves infiltration of the skin by activated T cells which stimulate the proliferation of keratinocytes. This dysregulation in keratinocyte turnover results in the formation of thick plaques. Other associated features include epidermal hyperplasia and parakeratosis. In addition, the epidermal cells fail to secrete lipids which results in flaky and scaly skin, which is typical of psoriasis.[8]

History and Physical

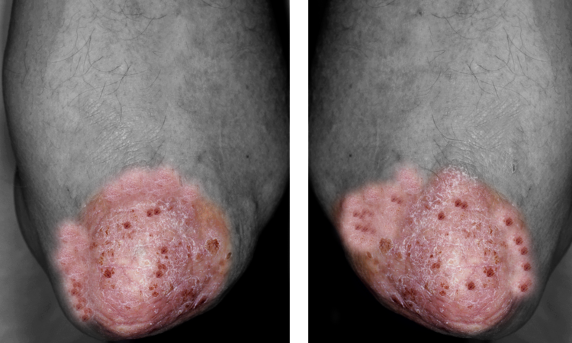

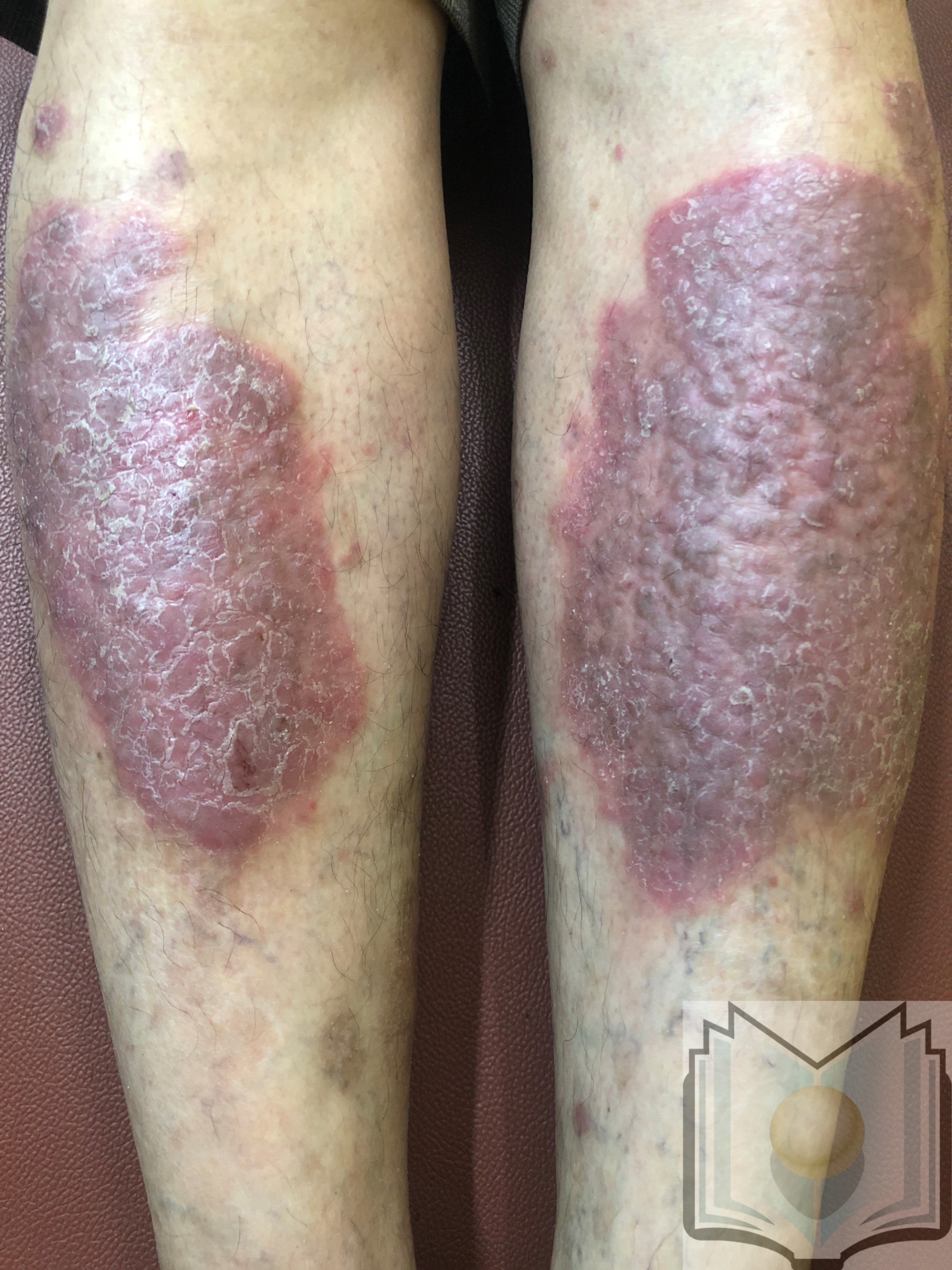

Psoriasis presents as well-defined erythematous plaques covered with silvery scales commonly over the scalp, and extensors of extremity, particularly over knees, elbows, and lumbosacral region. Psoriasis is classified into two types. Type 1 psoriasis, which has a positive family history, starts before age 40 and is associated with HLA-Cw6; while type 2 psoriasis does not show a family history, presents after age 40, and is not associated with HLA-Cw6. Psoriasis can present with different morphology in the form of plaque, guttate, rupioid, erythrodermic, pustular, inverse, elephantine, and psoriatic arthritis. Variation in a site is seen with the involvement of the scalp, palmoplantar region, genitals, and nails. Any injury to the skin in patients with psoriasis in the form of either mechanical, chemical, or radiational trauma induces lesions of psoriasis at that site which is called the Koebner phenomenon. It indicates the activeness of the disease.

Plaque psoriasis typically presents as erythematous plaques with silvery scales most commonly over extensors of extremities, i.e., on the elbows, knees, scalp, and back. It is the most common type of psoriasis which affects 85% to 90% of patients. On successive removal of psoriatic scales pinpoint bleeding points are seen. This is called the Auspitz sign which is used to confirm the diagnosis clinically.

Guttate psoriasis also called eruptive psoriasis is commonly seen in children after an upper respiratory tract infection with the streptococcal organism. It presents with erythematous and scaly raindrop-shaped lesions mainly over the trunk and back. It is the type of psoriasis having the best prognosis.

Pustular psoriasis presents with small non-infectious pus-filled lesions with erythema surrounding it. It is of two types localized and generalized. Generalized pustular psoriasis is associated with hypocalcemia and presents with sterile pustules on an erythematous plaque involving the whole body.

Erythrodermic psoriasis presents with widespread inflammation in the form of erythema and exfoliation of the skin covering more than 90% of the body area. It is associated with severe itching, swelling, and pain. It is the result of an exacerbation of unstable plaque psoriasis, following the abrupt withdrawal of systemic steroids. Complications of erythroderma include impairment in barrier functions of the skin, disturbance in basal metabolic rate, and increased cutaneous circulation in turn affecting the heart with cardiac failure.

Nail changes in psoriasis are seen as pitting, oil spots, subungual hyperkeratosis, nail dystrophy, and anchylosis.

Fissured tongue is the most common finding of oral psoriasis and has been reported to occur in 6.5% to 20% of people with psoriasis affecting the skin.

Inverse psoriasis is also called flexural psoriasis or intertriginous psoriasis. It appears as smooth, erythematous, and sharply demarcated patches affecting intertriginous areas like groins, armpits, intergluteal region, and inframammary region. The skin may be moist, macerated, and may contain fissures that may be malodorous, pruritic, or both. It needs to be differentiated from dermatophyte infection affecting these sites, which presents with central clearing and the active border with scales, vesicles, and pustules at the margin.

Sebopsoriasis is a form of psoriasis which typically manifests as red plaques with greasy scales. It commonly affects areas with increased sebum production such as the scalp, forehead, nasolabial folds, sternum, and retro-auricular folds.

Psoriatic arthritis is a form of chronic inflammatory arthritis which affects 30% of patients with psoriasis. It commonly occurs in association with skin and nail psoriasis. It typically involves painful inflammation of the joints and connective tissue commonly affecting the joints of the fingers and toes. It leads to sausage-shaped swelling of the fingers and toes known as dactylitis. Psoriatic arthritis can also affect the hips, knees, and spine presenting as spondylitis and sacroiliac joints with sacroiliitis.

Ocular features: psoriasis also affects the eyelid, conjunctiva, and cornea giving rise to trichiasis, ectropion, conjunctivitis, and corneal dryness. The most common eye feature is blepharitis which can lead to cicatricial ectropion, madarosis, and trichiasis. In some cases, anterior uveitis may be seen.[3][9]

Evaluation

Usually, diagnosis is made by clinical morphology and site of lesions. Histopathology is rarely necessary but may help to differentiate psoriasis from another dermatosis if the diagnosis is not easy. Characteristic changes in biopsy show parakeratosis, micro-abscess, the absence of granular lesions, regular elongation of ridges in the form of camel foot appearance, and spongiform pustules of Kogoj with dilated and tortuous capillaries in the dermal papilla.[10][11]

Laboratory studies

- One should order complete CBC, renal, and liver function tests

- Rheumatoid factor

- ESR may be elevated in erythrodermic and pustular psoriasis

- Uric acid levels are high in psoriasis

- If only hand and feet are involved, obtain scrappings for fungal studies

- Pregnancy test

- Hepatitis serology

- PPD

Treatment / Management

Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI) is the most widely used measurement tool which assesses the severity of the condition and allows for the evaluation of treatment efficiency. Topical therapy is used in mild to moderate psoriasis. Emollients and moisturizers may help in improving barrier function and retain the hydration of the stratum corneum. Topical agents used are coal tar, dithranol, corticosteroids, vitamin D analog, and retinoids are used initially. [12][13][14](B3)

- In patients who do not respond to the above treatments, methotrexate can be effective.

- Cyclosporine can be used to induce a clinical response but its use should be intermittent.

- When patients fail to respond to methotrexate, switch to biological agents; in some cases combine with methotrexate

Phototherapy includes PUVA therapy which combines psoralen with exposure to ultraviolet light (UVA), as well as NBUVB (Narrowband UVB light) with a range of 311 nanometers to 313 nanometers. NBUVB is equally effective without the side effects of psoralen like gastrointestinal upset, cataract formation, and carcinogenic effects. It can safely be given to children, pregnant and lactating females, and even older patients. Guttate psoriasis has been known to respond best to phototherapy

Systemic drugs are used in extensive cases, the involvement of nails and psoriatic arthritis. Methotrexate, retinoids, cyclosporine, and fumarates are possible options. Routine blood, liver functions, and renal functions should be monitored in patients on systemic therapy.

Biologicals are manufactured proteins that interrupt the immune process in psoriasis which are infliximab, adalimumab, etanercept, and interleukin antagonists. Before starting any biological agent, the patient should be worked up for tuberculosis and hepatitis. There is a serious risk of infections in these patients and all precautions should be taken that the patient is not severely immunocompromised.

Prolonged use of steroids and other immunosuppressives may delay wound healing.

Ocular psoriasis requires aggressive treatment with topical corticosteroids.

Patients with psoriasis should avoid all skin trauma for fear of inducing the Kobner reaction. In addition, psoriatic patients should avoid the use of beta-blockers, chloroquine, or NSAIDs. They should also avoid alcohol because of the risk of developing fatty liver.

Differential Diagnosis

- Eczema

- Seborrhoeic dermatitis

- Pityriasis rosea

- Mycosis fungoides (a form of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma)

- Secondary syphilis

Prognosis

Psoriasis is a chronic condition that is known to have a negative impact on the quality of life in patients as well as a family members. Psoriasis is a lifelong illness marked by relapses and remissions. About 10% of patients develop severe deforming arthritis. Remissions are experienced in 10-60% of patients. Over the course of the disease, psoriasis has been associated with depression, suicide, alcoholism, smoking, substance abuse, metabolic syndrome, and a variety of skin cancers. In addition, patients with psoriasis tend to have major medical comorbidities like kidney disease, heart disease, and joint problems. Several studies have noted a link between psoriasis and adverse cardiac events.

Pustular psoriasis and erythrodermic psoriasis may be life-threatening, while psoriatic arthritis affects the functional prognosis negatively.

Complications

- Secondary infections

- Poor cosmesis

- Psoriatic arthritis

- Risk of lymphoma

- Increased risk of adverse cardiac events

Deterrence and Patient Education

There is no specific diet for psoriasis but patients should eat a healthy diet. Patients should be educated on reducing the risk factors for heart disease. Exposure to sunlight is beneficial and patients should be encouraged to spend time outdoors. In addition, the patient should maintain a healthy body weight.

In the clinic, the patient should be screened for type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia. Finally, a consult with a psychiatrist is recommended as many patients develop severe depression.

Pearls and Other Issues

Summary of Guidelines

- Psoriasis is considered extensive when more than 10% BSA is involved

- When the condition occurs on the face, nails, scalp, genitals, flexures, and soles- it is also considered severe as these areas are hard to treat and associated with poor cosmesis.

- Biological therapy should be considered early if methotrexate is not well tolerated or in patients with active severe psoriasis.

- Assess response to treatment by noting a reduction in baseline disease severity and improvement in physical, social, and psychological functioning.

- Ustekinumab is the first line biological agent of choice. Secukinumab is another alternative

- Adalimumab is the first line biological agent of choice in patients with psoriatic arthropathy

- Infliximab is reserved for patients with severe disease in whom other biological agents cannot be used

- Women of childbearing age who are started on a biological agent should start effective contraception.

- Live vaccines are to be avoided in people taking biological agents. All vaccinations must be completed before starting biological agents.

- Patients with demyelinating disorders should not be treated with TNF antagonists

- Patients with heart failure should not be treated with TNF antagonists

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Psoriasis may be a skin disorder but its management is very complex and usually requires a team of professionals dedicated to this disease. Besides the dermatologist, the nephrologist, plastic surgeon, pharmacist, rheumatologist, and ophthalmologist should manage these patients. The key goal is to improve the quality of life by educating the patient about avoiding the triggers. The pharmacist should educate the patient on the use of moisturizers and managing dry skin. Further compliance with medications is vital; plus the pharmacist should ensure that the patient is on no medications that can cause flare-ups. The nurse should educate the patient on changes in lifestyle by avoiding alcohol, smoking, stress, and dry cold weather. While the sun is beneficial, too much should be avoided. The nurse should monitor the patient for self-harm and refer the patient to a mental health counselor. Finally, the patient should be told to eat healthily, exercise regularly, and maintain a healthy weight. All patients with psoriasis need lifelong follow-up because relapses are common.[15] An interprofessional team approach to management will yield improved outcomes.[Level V]

Outcomes

Even though psoriasis is a benign skin disorder, it is a lifelong illness with no cure. Everyone undergoes remissions and relapses and overall it leads to poor quality of life. Today there are several reports indicating that psoriasis also increases the risk of adverse cardiac events. Psoriasis also is associated with alcohol use, smoking, depression, risk of lymphoma, suicide, adverse drug reactions, and several types of skin cancers. Evidence continues to mount that psoriasis is associated with hypertension, renal disease, and heart disease. Overall, patients with psoriasis involving the palms and soles tend to have a much poorer quality of life than those who have psoriasis on other parts of the body.[16][17][18] [Level 5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Elman SA, Weinblatt M, Merola JF. Targeted therapies for psoriatic arthritis: an update for the dermatologist. Seminars in cutaneous medicine and surgery. 2018 Sep:37(3):173-181. doi: 10.12788/j.sder.2018.045. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30215635]

Yiu ZZ, Warren RB. Ustekinumab for the treatment of psoriasis: an evidence update. Seminars in cutaneous medicine and surgery. 2018 Sep:37(3):143-147. doi: 10.12788/j.sder.2018.040. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30215630]

Yang EJ, Beck KM, Sanchez IM, Koo J, Liao W. The impact of genital psoriasis on quality of life: a systematic review. Psoriasis (Auckland, N.Z.). 2018:8():41-47. doi: 10.2147/PTT.S169389. Epub 2018 Aug 28 [PubMed PMID: 30214891]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGamret AC, Price A, Fertig RM, Lev-Tov H, Nichols AJ. Complementary and Alternative Medicine Therapies for Psoriasis: A Systematic Review. JAMA dermatology. 2018 Nov 1:154(11):1330-1337. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.2972. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30193251]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceNguyen CT, Bloch Y, Składanowska K, Savvides SN, Adamopoulos IE. Pathophysiology and inhibition of IL-23 signaling in psoriatic arthritis: A molecular insight. Clinical immunology (Orlando, Fla.). 2019 Sep:206():15-22. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2018.09.002. Epub 2018 Sep 6 [PubMed PMID: 30196070]

Larsabal M, Ly S, Sbidian E, Moyal-Barracco M, Dauendorffer JN, Dupin N, Richard MA, Chosidow O, Beylot-Barry M. GENIPSO: a French prospective study assessing instantaneous prevalence, clinical features and impact on quality of life of genital psoriasis among patients consulting for psoriasis. The British journal of dermatology. 2019 Mar:180(3):647-656. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17147. Epub 2018 Nov 1 [PubMed PMID: 30188572]

Eder L, Widdifield J, Rosen CF, Cook R, Lee KA, Alhusayen R, Paterson MJ, Cheng SY, Jabbari S, Campbell W, Bernatsky S, Gladman DD, Tu K. Trends in the Prevalence and Incidence of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis in Ontario, Canada: A Population-Based Study. Arthritis care & research. 2019 Aug:71(8):1084-1091. doi: 10.1002/acr.23743. Epub 2019 Jul 11 [PubMed PMID: 30171803]

Kahn J, Deverapalli SC, Rosmarin D. JAK-STAT signaling pathway inhibition: a role for treatment of various dermatologic diseases. Seminars in cutaneous medicine and surgery. 2018 Sep:37(3):198-208. doi: 10.12788/j.sder.2018.041. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30215638]

Caiazzo G, Fabbrocini G, Di Caprio R, Raimondo A, Scala E, Balato N, Balato A. Psoriasis, Cardiovascular Events, and Biologics: Lights and Shadows. Frontiers in immunology. 2018:9():1668. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01668. Epub 2018 Aug 13 [PubMed PMID: 30150978]

Trayes KP, Savage K, Studdiford JS. Annular Lesions: Diagnosis and Treatment. American family physician. 2018 Sep 1:98(5):283-291 [PubMed PMID: 30216021]

Vázquez-Herrera NE, Sharma D, Aleid NM, Tosti A. Scalp Itch: A Systematic Review. Skin appendage disorders. 2018 Aug:4(3):187-199. doi: 10.1159/000484354. Epub 2017 Nov 29 [PubMed PMID: 30197900]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePerez-Chada LM, Cohen JM, Gottlieb AB, Duffin KC, Garg A, Latella J, Armstrong AW, Ogdie A, Merola JF. Achieving international consensus on the assessment of psoriatic arthritis in psoriasis clinical trials: an International Dermatology Outcome Measures (IDEOM) initiative. Archives of dermatological research. 2018 Nov:310(9):701-710. doi: 10.1007/s00403-018-1855-3. Epub 2018 Aug 25 [PubMed PMID: 30167814]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSchadler ED, Ortel B, Mehlis SL. Biologics for the primary care physician: Review and treatment of psoriasis. Disease-a-month : DM. 2019 Mar:65(3):51-90. doi: 10.1016/j.disamonth.2018.06.001. Epub 2018 Jul 20 [PubMed PMID: 30037762]

Dauden E, Blasco AJ, Bonanad C, Botella R, Carrascosa JM, González-Parra E, Jodar E, Joven B, Lázaro P, Olveira A, Quintero J, Rivera R. Position statement for the management of comorbidities in psoriasis. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2018 Dec:32(12):2058-2073. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15177. Epub 2018 Aug 14 [PubMed PMID: 29992631]

Luchetti MM, Benfaremo D, Campanati A, Molinelli E, Ciferri M, Cataldi S, Capeci W, Di Carlo M, Offidani AM, Salaffi F, Gabrielli A. Clinical outcomes and feasibility of the multidisciplinary management of patients with psoriatic arthritis: two-year clinical experience of a dermo-rheumatologic clinic. Clinical rheumatology. 2018 Oct:37(10):2741-2749. doi: 10.1007/s10067-018-4238-4. Epub 2018 Jul 29 [PubMed PMID: 30056525]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSears AV, Szlumper C, Liu KW, Smith CH, Barker JNWN, Pink AE. Clinical outcomes in patients on secukinumab (Cosentyx(®) ) within a specialist psoriasis clinic: a single centre, retrospective cohort study. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2019 Feb:33(2):e89-e91. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15245. Epub 2018 Oct 1 [PubMed PMID: 30198598]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMurage MJ, Tongbram V, Feldman SR, Malatestinic WN, Larmore CJ, Muram TM, Burge RT, Bay C, Johnson N, Clifford S, Araujo AB. Medication adherence and persistence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and psoriatic arthritis: a systematic literature review. Patient preference and adherence. 2018:12():1483-1503. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S167508. Epub 2018 Aug 21 [PubMed PMID: 30174415]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLangenbruch A, Radtke MA, Gutknecht M, Augustin M. Does the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) underestimate the disease-specific burden of psoriasis patients? Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2019 Jan:33(1):123-127. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15226. Epub 2018 Sep 27 [PubMed PMID: 30160802]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence