Introduction

Originally known as "punch drunk" syndrome and first documented in boxers in the 1920s, chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) has grown to be a well-known topic in the sports medicine community.[1] Repetitive head injury syndrome or the newly coined "chronic traumatic encephalopathy" (CTE) is a unique variant of a progressive neurodegenerative entity seen especially among people who are indulged in contact sports or working in military services wherein there is added risk of repeated head injuries.[1]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Repeated head injury plays a pivotal role in the genesis of this entity. The APOE epsilon-4 allele has shown to harbinger added risk of developing attenuated cognitive decline following repeated head impacts.[1] Similarly, positive associations also have links to cognitive reserve, early age of first exposure (less than 12 years of age) and the cumulative dose of head impacts with the severity of ensuing neurological sequelae in the future.[1]

Epidemiology

There are 4 million sports-related concussions reported annually in the US alone.[1] There is reportedly a 17% incidence of sport attributable neurological ailments among boxers. In a study carried out in the Mayo Clinic Brain Bank, the CTE pathology was present in 32% of athletes indulged in contact sports. Similarly, in the largest case series comprising among 177 former professional football players, CTE was diagnosed in up to 87% of them.[1] A recent study has also found high neuropathological evidence of CTE among football players who donated their brains for research purposes.[2]

Pathophysiology

Immuno-excitotoxicity plays a central role in the pathogenesis of chronic traumatic encephalopathy wherein repeatedly primed microglia, following a repetitive head injury, fail to switch from a neuro-destructive mode to a reparative mode, thereby attenuating the inflammatory insult to the brain by providing a favorable milieu amidst glutamate toxicity.[3]

Repetitive head injury, owing to axonal degeneration and microtubular disintegration, leads to tau oligomerization which later transforms to neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) thereby affecting neuronal crosstalk and networking. Such a process eventually leads to tau propagation thereby activating inflammatory cascades and ultimately hampering blood-brain barrier permeability.[4]

Histopathology

Perivascular tau deposition within the sulcal depths is an essential prerequisite for the diagnosis of chronic traumatic encephalopathy as per the first consensus from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) and the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB).[1]

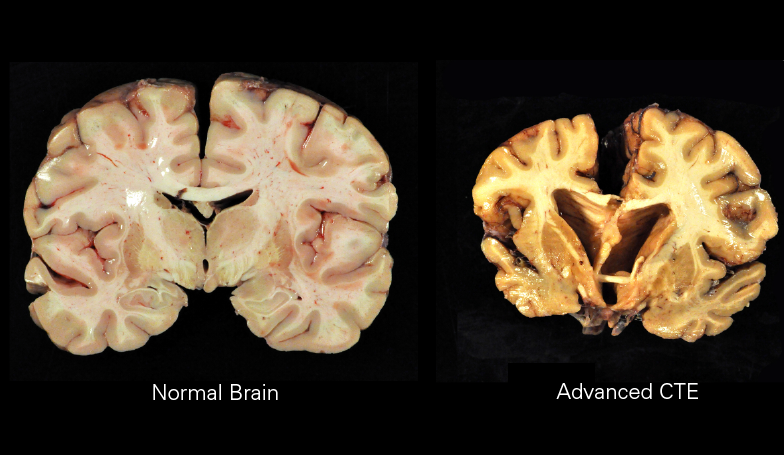

Grossly there are features of regional atrophy (most commonly frontal lobe), ventriculomegaly, wasting of the corpus callosum and characteristic fenestration of the septum pellucidum. The regions of atrophy parallel high concentrations of glutamate receptors thereby connoting the role of excitotoxicity in the pathogenesis of the entity.[1]

Microscopically, deposition of neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) and neuropil threads (NTs) are predominant findings. However, contrary to other tauopathies, beta-amyloid is seen in only 40% to 45% of patients with CTE, the tau distribution in an uneven fashion within superficial cortical laminae with sparing of the temporal lode. The NFTs in chronic traumatic encephalopathy deposit in perivascular fashion at the sulcal depths.[5]

There are reports of four histomorphologic phenotypes of CTE[6]

- Type 1 - NFT and NTs in cerebral cortex and brainstem only

- Type 2 - Type 1 + B amyloid deposition

- Type 3 - NFT and NTs in brainstem only

- Type 4 - NFT and NTs in the cortex, subcortex, brainstem, basal ganglion but sparing cerebellum

History and Physical

The patient history will include some form of repetitive head trauma and usually involves an individual that is involved with contact sports or the military.

As described by Browne, the disease process begins with the first stage of affective disturbances followed by the stage of social instability, behavioral changes with subtle features of early Parkinsonism which eventually progresses to the third stage of cognitive dysfunction, dementia, and full-blown Parkinsonism.[7]

These changes have been attributed to the disease process predominantly affecting the Papez circuit.[8]

Evaluation

A thorough neurologic examination is necessary with particular emphasis on the mental status examination.[1]

However, definitive chronic traumatic encephalopathy diagnosis is only through post-mortem autopsy and facilitated by immunohistochemistry for p-tau.[4]

Recent advances in the imaging armamentarium such as FDDNP PET and biomarkers such as CCL11 and CSF sTREM2 have shown promises in providing valuable input for supporting the diagnosis.[4][9][10]

Recently, a pivotal finding of a characteristic hydrophobic cavity formed within the β-helix of tau filaments from CTE has paved newer insights in finding new targets in early diagnosis of the condition.[11]

Treatment / Management

No definitive treatment exists for chronic traumatic encephalopathy. However novel drugs such as salsalate that precisely inhibit the essential steps of acetylation before phosphorylation of the paired helical filament-6 (PHF-6) motif, thereby inhibiting microglial activation are under research.[4] The disease is managed similarly to other forms of dementia in that it is supportive treatment.

Differential Diagnosis

The characteristic finding that helps differentiate chronic traumatic encephalopathy from other tauopathies such as Alzheimer's and Lewi body dementia is the perivascular deposition of tau-immunoreactive astrocytes within the sulcal depths of superficial cortical layers.[4]

Additionally, the dimensions of NFTs in CTE are larger along with co-localized aggregates of transactive response DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43).[4]

Treatment Planning

Treatment of chronic traumatic encephalopathy is currently supportive.[1]

The best modality in minimizing the incidence of CTE is strict adherence to preventive measures. A provision for safe team and a safe playing environment culture and strict upholding to rules governing the return to play policy is paramount for the same.[5]

Staging

The research diagnostic criteria describe four subtypes of this condition[1]:

- Behavioral/mood variant

- A cognitive variant, which occurs later in life

- Mixed variant

- Dementia form

There are four stages of chronic traumatic encephalopathy described according to the distribution of NFTs and associated clinical signs and symptoms namely[1]:

- Stage 1 - Perivascular deposits of NFTs in the sulcal depths characterized by headache and loss of concentration

- Stage 2 - Stage 1 + NFTs within the nucleus basalis of Meynert and locus coeruleus characterized by mood swings and short-term memory loss

- Stage 3 - Stage 2 + atrophy, wasting of the corpus callosum, septal abnormalities, ventriculomegaly, depigmentation of the substantia nigra and widespread deposition of p-tau characterized by cognitive impairment, executive dysfunction, and visuospatial abnormalities

- Stage 4 - Stage 3 + further atrophy, gliosis and hippocampal sclerosis characterized by profound memory loss and florid parkinsonian features

Prognosis

The prognosis is usually good in many patients, however, the incidence of neurodegenerative mortality in former players was found to be 3 times higher than their healthy counterparts. There is a link between CTE and the development of early-onset Parkinson dementia.[12]

Complications

Chronic traumatic encephalopathy is progressive in almost 68% of patients. In the small subgroup with predominantly behavioral or mood symptoms, it may remain stable for years before progressing to other stages after a latency of 11 to 14 years.[1]

The neurodegenerative process sequentially sets in the stages of social instability, behavioral changes followed by dementia.[1]

There is also an increased risk of committing suicide among these subsets of patients.

Deterrence and Patient Education

The cornerstone in the management of chronic traumatic encephalopathy is through preventive measures aimed at reducing the incidence among high-risk people. Promoting a safe playing environment and strict adherence to early diagnosing and safeguarding high-risk subgroups from added head impacts play a paramount role in minimizing the incidence of CTE. There is still no "silver bullet" in the management algorithm of this condition, and thereby symptomatic management is the only available option.

Pearls and Other Issues

Despite recent ushers in the attention this entity has received, and resources spent for the same, we still seem to be moving in circles rather than moving forward in our quest to better understanding the disease entity, with many of our views still based on supposition rather than on facts, as had been advocated by Corsellis four decades earlier.[7]

However, tau imaging and relevant CSF biomarkers have shown promise in becoming surrogate markers for the definitive diagnosis of patients with CTE.[1]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

There is the utmost need of large multicentric randomized controlled trials to evaluate the efficacy of currently available radiological and biochemical armamentariums aimed at early diagnosis of chronic traumatic encephalopathy in vivo. Furthermore, research is underway in evaluating newer frontiers in targeting critical steps such as oligomerization and propagation of tau proteins to halt the disease process in the early stages itself. The belief is that cognitive training might offer some way of reducing possible symptoms. The use of these mental exercises in a professional athlete's career or earlier in their life may prove more effective.[13]

The primary provider, nurse practitioner, sports physician, neurologist, and specialty-trained nursing staff need to work together in a collaborative, interprofessional team approach to chronic traumatic encephalopathy. As prevention is the optimal management strategy, this includes educating the patient on sports safety, and that means wearing a helmet during contact sports, bicycling and ice hockey.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Turk KW, Budson AE. Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy. Continuum (Minneapolis, Minn.). 2019 Feb:25(1):187-207. doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000000686. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30707193]

Mez J, Daneshvar DH, Kiernan PT, Abdolmohammadi B, Alvarez VE, Huber BR, Alosco ML, Solomon TM, Nowinski CJ, McHale L, Cormier KA, Kubilus CA, Martin BM, Murphy L, Baugh CM, Montenigro PH, Chaisson CE, Tripodis Y, Kowall NW, Weuve J, McClean MD, Cantu RC, Goldstein LE, Katz DI, Stern RA, Stein TD, McKee AC. Clinicopathological Evaluation of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in Players of American Football. JAMA. 2017 Jul 25:318(4):360-370. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.8334. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28742910]

Blaylock RL, Maroon J. Immunoexcitotoxicity as a central mechanism in chronic traumatic encephalopathy-A unifying hypothesis. Surgical neurology international. 2011:2():107. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.83391. Epub 2011 Jul 30 [PubMed PMID: 21886880]

Tharmaratnam T, Iskandar MA, Tabobondung TC, Tobbia I, Gopee-Ramanan P, Tabobondung TA. Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in Professional American Football Players: Where Are We Now? Frontiers in neurology. 2018:9():445. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00445. Epub 2018 Jun 19 [PubMed PMID: 29971037]

Saulle M, Greenwald BD. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy: a review. Rehabilitation research and practice. 2012:2012():816069. doi: 10.1155/2012/816069. Epub 2012 Apr 10 [PubMed PMID: 22567320]

Omalu B, Bailes J, Hamilton RL, Kamboh MI, Hammers J, Case M, Fitzsimmons R. Emerging histomorphologic phenotypes of chronic traumatic encephalopathy in American athletes. Neurosurgery. 2011 Jul:69(1):173-83; discussion 183. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e318212bc7b. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21358359]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceCorsellis JA, Bruton CJ, Freeman-Browne D. The aftermath of boxing. Psychological medicine. 1973 Aug:3(3):270-303 [PubMed PMID: 4729191]

Eggers AE. Redrawing Papez' circuit: a theory about how acute stress becomes chronic and causes disease. Medical hypotheses. 2007:69(4):852-7 [PubMed PMID: 17376605]

Cherry JD, Stein TD, Tripodis Y, Alvarez VE, Huber BR, Au R, Kiernan PT, Daneshvar DH, Mez J, Solomon TM, Alosco ML, McKee AC. CCL11 is increased in the CNS in chronic traumatic encephalopathy but not in Alzheimer's disease. PloS one. 2017:12(9):e0185541. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0185541. Epub 2017 Sep 26 [PubMed PMID: 28950005]

Alosco ML, Tripodis Y, Fritts NG, Heslegrave A, Baugh CM, Conneely S, Mariani M, Martin BM, Frank S, Mez J, Stein TD, Cantu RC, McKee AC, Shaw LM, Trojanowski JQ, Blennow K, Zetterberg H, Stern RA. Cerebrospinal fluid tau, Aβ, and sTREM2 in Former National Football League Players: Modeling the relationship between repetitive head impacts, microglial activation, and neurodegeneration. Alzheimer's & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer's Association. 2018 Sep:14(9):1159-1170. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.05.004. Epub 2018 Jul 23 [PubMed PMID: 30049650]

Falcon B, Zivanov J, Zhang W, Murzin AG, Garringer HJ, Vidal R, Crowther RA, Newell KL, Ghetti B, Goedert M, Scheres SHW. Novel tau filament fold in chronic traumatic encephalopathy encloses hydrophobic molecules. Nature. 2019 Apr:568(7752):420-423. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1026-5. Epub 2019 Mar 20 [PubMed PMID: 30894745]

Adams JW, Alvarez VE, Mez J, Huber BR, Tripodis Y, Xia W, Meng G, Kubilus CA, Cormier K, Kiernan PT, Daneshvar DH, Chua AS, Svirsky S, Nicks R, Abdolmohammadi B, Evers L, Solomon TM, Cherry JD, Aytan N, Mahar I, Devine S, Auerbach S, Alosco ML, Nowinski CJ, Kowall NW, Goldstein LE, Dwyer B, Katz DI, Cantu RC, Stern RA, Au R, McKee AC, Stein TD. Lewy Body Pathology and Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy Associated With Contact Sports. Journal of neuropathology and experimental neurology. 2018 Sep 1:77(9):757-768. doi: 10.1093/jnen/nly065. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30053297]

Asken BM, Sullan MJ, Snyder AR, Houck ZM, Bryant VE, Hizel LP, McLaren ME, Dede DE, Jaffee MS, DeKosky ST, Bauer RM. Factors Influencing Clinical Correlates of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE): a Review. Neuropsychology review. 2016 Dec:26(4):340-363 [PubMed PMID: 27561662]

Eaton RG, Lonser RR. History of biological, mechanistic, and clinical understanding of concussion. Neurosurgical focus. 2024 Jul:57(1):E2. doi: 10.3171/2024.5.FOCUS24149. Epub [PubMed PMID: 38950436]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceArciniega H, Baucom ZH, Tuz-Zahra F, Tripodis Y, John O, Carrington H, Kim N, Knyazhanskaya EE, Jung LB, Breedlove K, Wiegand TLT, Daneshvar DH, Rushmore RJ, Billah T, Pasternak O, Coleman MJ, Adler CH, Bernick C, Balcer LJ, Alosco ML, Koerte IK, Lin AP, Cummings JL, Reiman EM, Stern RA, Shenton ME, Bouix S. Brain morphometry in former American football players: Findings from the DIAGNOSE CTE research project. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2024 Mar 27:():. pii: awae098. doi: 10.1093/brain/awae098. Epub 2024 Mar 27 [PubMed PMID: 38533783]