Introduction

Residual volume (RV) is the volume of air remaining in the lungs after maximum forceful expiration. In other words, it is the volume of air that cannot be expelled from the lungs, thus causing the alveoli to remain open at all times. The residual volume remains unchanged regardless of the lung volume at which expiration was started.[1] Reference values for residual volume are 1 to 1.2 L, but these values are dependent on factors including age, gender, height, weight, and physical activity levels.[2][3] See Image. Residual Volume.

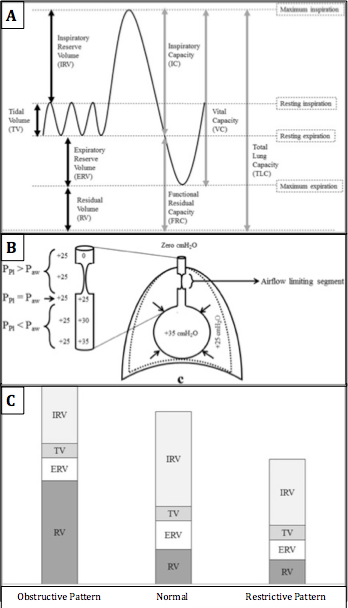

The residual volume is an important component of the total lung capacity (TLC) and the functional residual capacity (FRC). TLC is the total volume of the lungs at maximal inspiration which is about 6 L on average, though true values are dependent on the same factors that affect residual volume.[4] FRC is the amount of air remaining in the lungs after a normal, physiologic expiration (Figure 1A). The TLC, FRC, and RV are absolute lung volumes and cannot be measured directly with spirometry. Instead, they must be calculated using indirect measurement techniques such as gas dilution or body plethysmography. Calculating the residual volume can give an indication of lung physiology and pathology.[5]

Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Function

The residual volume functions to maintain the patency of alveoli even after maximal forced expiration. In healthy lungs, the air that makes up the residual volume is utilized for continual gas exchange between breaths. Inspiration then draws atmospheric oxygen into the lungs to replenish the oxygen-depleted residual air for gas exchange in the alveoli.

Mechanism

Although breathing mechanics are complex, it is important to remember that air will flow from high-pressure areas to low-pressure areas. During tidal breathing, the inspiration and expiration at physiologic rest, the volume of air entering and leaving the lungs is known as the tidal volume (TV). On tidal inspiration, inspiratory muscle contraction increases the volume of the chest causing the intrapleural pressure (Ppl) to drop from -5 cm H2O to -8 cm H2O. The decreased Ppl causes the alveolar pressure (Palv) to decrease 1 cm H2O below atmospheric pressure. As a result, air from the relatively high-pressure atmosphere flows into the low-pressure alveoli. Inspiration is an active process requiring the rhythmic contraction of inspiratory muscles that work to expand the chest cavity. Tidal expiration is a passive process that works in reverse. The inspiratory muscles relax, decreasing the size of the chest cavity, and increasing Ppl and Palv. Once Palv is greater than atmospheric pressure, air flows out of the lungs.

Residual volume can be understood by investigation of breathing that exceeds tidal volumes. Following maximal inspiration, the volume of air that leaves the lungs during a maximal force expiration is known as the vital capacity (VC). VC is composed of the tidal volume, expiratory reserve volume (ERV), and inspiratory reserve volume (IRV). The ERV is the volume of air that can be forcefully exhaled after a normal resting expiration, leaving only the RV in the lungs. Forcefully exhaling the ERV is an active process requiring the contraction of expiratory muscles in the chest and abdomen. This increases Ppl and Palv above atmospheric pressure. Due to the elastic recoil of the alveoli, the pressure inside of the alveoli remains higher than that of the pleura, and the alveoli remain open. The pressure inside the airways (Paw) slowly decreases as you move up from the alveoli to the trachea as a result of increased airway resistance. In sections of small, non-cartilaginous airways, pleural pressure is greater than airway pressure and causes a collapse of the airway (Figure 1B). The air that remains in the lungs after the collapse of all small airways is the residual volume.

Related Testing

There are no methods to measure residual volume directly. Other lung volumes and capacities must first be measured directly before RV can be calculated. The first step in calculating RV is to determine the FRC. Measurement of the FRC can be done using one of the following three tests.

Helium Dilution Test

In this test, the patient inhales a known volume of air (V1) containing a known fraction of helium (FHe1) at end-expiration of tidal breathing, where the volume of air left in the lungs is equal to FRC. A spirometer measures the fraction of helium after equilibration in the lungs (FHe2).

- FRC = V1(FHe1-FHe2) / FHe2

Nitrogen Washout

The nitrogen washout test utilizes the nitrogen that makes up 78% of atmospheric air. A patient breathes through a 2-way valve connected to 100% oxygen on inspiration and a collection spirometer on expiration. The spirometer measures the volume of air and fraction of nitrogen expired with each breath. Once the fraction of nitrogen is below 1.5% for 3 consecutive breaths, the test is complete. The initial amount of nitrogen in the lungs must be equal to the total amount of nitrogen exhaled, and thus the FRC can be calculated.

- FRC = V exhaled * C exhaled N2 / C initial alveolar N2

Body Plethysmography

Plethysmography is based on Boyle’s law of gases. In a closed system at a constant temperature, the product of pressure and volume of a known mass of gas is constant. That is to say, pressure and volume are inversely proportional.

- P1V1 = P2V2

To conduct the test, a patient is placed inside an enclosed chamber and breathes through a spirometer that can measure changes in pressure and volume. After a period of tidal breathing, the spirometer is closed at end-expiration, and the patient breathes against it. Changes in pressure at the mouthpiece are recorded. As the patient exhales, the volume of the thoracic cavity can be calculated by recording the change in pressure of the entire chamber. This test is the most accurate measure of FRC, but also the most expensive.

Once the FRC has been measured using one of these three methods, the expiratory reserve volume (ERV) and vital capacity (VC) are measured using standard spirometry. Calculations of TV and TLC can be made using the measured FRC, ERV, and VC values and the following equations:

- RV = FRC - ERV

- TLC = VC + RV

Clinical Significance

Obstructive Lung Disease (OLD)

Obstructive lung diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, and bronchiectasis, are characterized by airway inflammation, easily collapsible airways, expiratory flow obstruction, and air trapping that results in elevated RV relative to healthy lungs. In obstructive lung disease, factors such as inflammation, bronchoconstriction, excessive mucus, and decreased elastic recoil cause increased airway resistance and lead to earlier small airway closure during expiration. The premature airway closure increases the volume of air retained in the lungs at the end of expiration; this is referred to as air trapping. This trapped air results in pulmonary hyperinflation. Therefore patients with obstructive lung disease have elevated TLC, FRC, and RV (Figure 1C).[6][7][8] These changes are reflected by the characteristic left shift associated with OLD seen on the flow-volume loop during pulmonary function testing.

Body plethysmography yields a higher FRC in patients with obstructive lung disease than those measured by gas dilution techniques because it includes both well-ventilated and poorly ventilated areas of the lung. RV is generally the first volume to increase in obstructive lung disease and can be a good measure to evaluate early disease states. Additional findings on spirometry for OLD include decreased forced expiratory volume in the first second of expiration (FEV1), decreased forced vital capacity (FVC), and FEV1/FVC ratio <70% because FEV1 decreases more than FVC.

The RV/TLC ratio is used as a measure of resting pulmonary hyperinflation in patients with COPD. An elevated RC/TLC ratio is a significant risk factor for all-cause mortality in COPD patients.[9]

Restrictive Lung Disease (RLD)

Restrictive lung diseases are a result of processes that restrict pulmonary expansion. The restriction can be related to intrinsic diseases such as pulmonary fibrosis and sarcoidosis, or extrinsic processes like kyphosis and obesity. In either case, the result is restricted airway expansion that reduces the driving force for airflow into the lungs created by the negative pressure gradient which causes decreased lung volumes and inadequate ventilation. TLC, FRC, and RV will all be decreased in restrictive lung disease. These changes are reflected by the characteristic right shift associated with RLD seen on the flow-volume loop during pulmonary function testing. Findings of spirometry include decreased FEV1 and FVC as seen in OLD, but the decrease in FEV1 and FVC is more uniform, or even more so in FVC, which results in a normal or elevated FEV1/FVC ratio.

The effects of obesity on lung function are a growing concern as the prevalence and severity of obesity increase. Studies have shown that increasing body mass index (BMI) correlates with lower VC, TLC, and RV, but these values remain within normal limits. Significant decreases in FRC and ERV are seen as BMI increases to the extent that FRC approaches RV.[10][11][12]

Drowning

An interesting clinical use for residual volume is applied during post-mortem autopsies of drowning victims. The residual volume of air in the lungs can only be removed if it is replaced by another substance. In the case of drowning victims, water will replace the residual air in the lungs. During autopsies, medical examiners can clamp the trachea and submerge the lungs in water. If the lungs sink, no residual air remains, so it is likely the person drowned after inhaling large amounts of water. However, if the lungs float, the residual volume of air remains in the lungs. The residual volume was not replaced by water, so it is likely the person died before entering the water.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Residual Volume. Standard lung volumes and capacities (A), lung pressures at forceful expiration (B), and typical changes in lung volumes seen in restrictive and obstructive lung disease (C).

Contributed by Lutfi, 2017; Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

References

Mortola JP. How to breathe? Respiratory mechanics and breathing pattern. Respiratory physiology & neurobiology. 2019 Mar:261():48-54. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2018.12.005. Epub 2018 Dec 31 [PubMed PMID: 30605732]

Kraemer R, Smith HJ, Matthys H. Normative reference equations of airway dynamics assessed by whole-body plethysmography during spontaneous breathing evaluated in infants, children, and adults. Physiological reports. 2021 Sep:9(17):e15027. doi: 10.14814/phy2.15027. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34514738]

Haynes JM, Kaminsky DA, Stanojevic S, Ruppel GL. Pulmonary Function Reference Equations: A Brief History to Explain All the Confusion. Respiratory care. 2020 Jul:65(7):1030-1038. doi: 10.4187/respcare.07188. Epub 2020 Mar 10 [PubMed PMID: 32156791]

Guillien A,Soumagne T,Regnard J,Degano B, [The new reference equations of the Global Lung function Initiative (GLI) for pulmonary function tests]. Revue des maladies respiratoires. 2018 Dec; [PubMed PMID: 30448081]

Krol K, Morgan MA, Khurana S. Pulmonary Function Testing and Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing: An Overview. The Medical clinics of North America. 2019 May:103(3):565-576. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2018.12.014. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30955522]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKim J, Kim MJ, Sol IS, Sohn MH, Yoon H, Shin HJ, Kim KW, Lee MJ. Quantitative CT and pulmonary function in children with post-infectious bronchiolitis obliterans. PloS one. 2019:14(4):e0214647. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0214647. Epub 2019 Apr 1 [PubMed PMID: 30934017]

Clair C, Mueller Y, Livingstone-Banks J, Burnand B, Camain JY, Cornuz J, Rège-Walther M, Selby K, Bize R. Biomedical risk assessment as an aid for smoking cessation. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2019 Mar 26:3(3):CD004705. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004705.pub5. Epub 2019 Mar 26 [PubMed PMID: 30912847]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGallucci M, Carbonara P, Pacilli AMG, di Palmo E, Ricci G, Nava S. Use of Symptoms Scores, Spirometry, and Other Pulmonary Function Testing for Asthma Monitoring. Frontiers in pediatrics. 2019:7():54. doi: 10.3389/fped.2019.00054. Epub 2019 Mar 5 [PubMed PMID: 30891435]

Shin TR, Oh YM, Park JH, Lee KS, Oh S, Kang DR, Sheen S, Seo JB, Yoo KH, Lee JH, Kim TH, Lim SY, Yoon HI, Rhee CK, Choe KH, Lee JS, Lee SD. The Prognostic Value of Residual Volume/Total Lung Capacity in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Journal of Korean medical science. 2015 Oct:30(10):1459-65. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2015.30.10.1459. Epub 2015 Sep 12 [PubMed PMID: 26425043]

Kishaba T. Acute Exacerbation of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania). 2019 Mar 16:55(3):. doi: 10.3390/medicina55030070. Epub 2019 Mar 16 [PubMed PMID: 30884853]

de Carvalho M, Swash M, Pinto S. Diaphragmatic Neurophysiology and Respiratory Markers in ALS. Frontiers in neurology. 2019:10():143. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.00143. Epub 2019 Feb 21 [PubMed PMID: 30846968]

Lumb AB, Pre-operative respiratory optimisation: an expert review. Anaesthesia. 2019 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 30604419]