Introduction

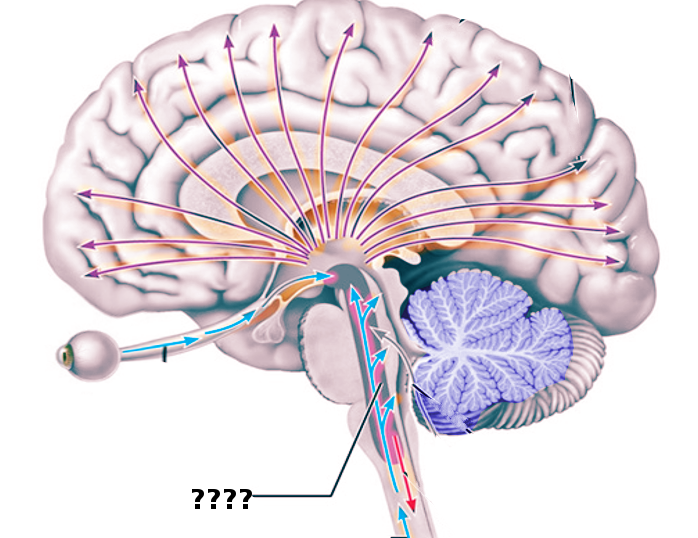

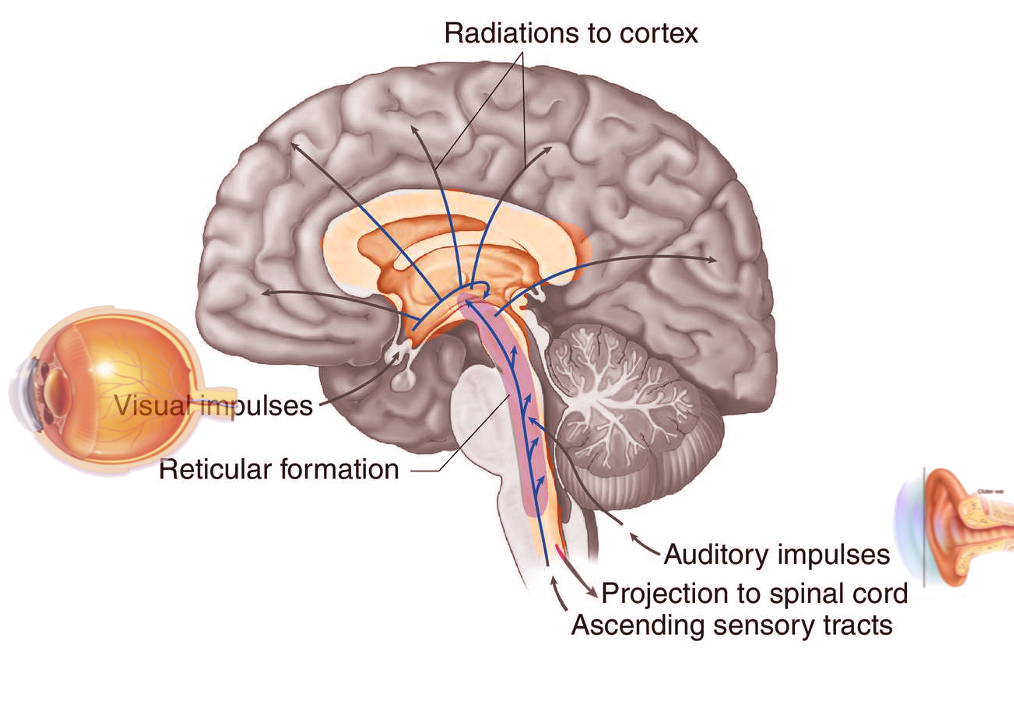

The reticular activating system (RAS) is a component of the reticular formation in vertebrate brains located throughout the brainstem. Between the brainstem and the cortex, multiple neuronal circuits ultimately contribute to the RAS.[1] These circuits function to allow the brain to modulate between slow sleep rhythms and fast sleep rhythms, as seen on EEG. By doing this, the nuclei that form the RAS play a significant role in coordinating both the sleep-wake cycle and wakefulness. The groupings of neurons that together make up the RAS are ultimately responsible for attention, arousal, modulation of muscle tone, and the ability to focus.[2]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The RAS is a component of the reticular formation, found in the anterior-most segment of the brainstem. The reticular formation receives input from the spinal cord, sensory pathways, thalamus, and cortex and has efferent connections throughout the nervous system. The RAS itself is primarily composed of four main components that each contain groupings of nuclei. These are the locus coeruleus, raphe nuclei, posterior tuberomammillary hypothalamus, and pedunculopontine tegmentum. Each is unique in the neuropeptides they release. In large part, these centers are activated by the lateral hypothalamus (LH), which releases the neuropeptide orexin in response to the light hitting the eyes, which then stimulates arousal and the transition from sleep to waking.[3]

The locus coeruleus is located within the upper dorsolateral pons of the brainstem. It is activated directly by orexin from the lateral hypothalamus, and in response, releases norepinephrine. Its excitatory functions are widely distributed within the brain, acting on both the alpha and beta receptors of neurons and glial cells distributed throughout the cortex. It functions primarily upon waking and in arousal.[4][5]

The raphe nuclei are located midline throughout the brainstem within the pons, midbrain, and medulla. The majority of neurons located in the raphe nuclei are serotonergic. The more rostral raphe nuclei appear to be important in various bodily functions, including pain sensation and mood regulation. In the context of the RAS, these nuclei communicate with the suprachiasmatic nucleus, playing a role in circadian rhythms, and contributing to arousal and attention.[6]

The tuberomammillary nucleus is located within the posterior aspect of the hypothalamus. The neurons that make up these nuclei are primarily histaminergic and serve as the primary source of histamine projections in the brain. They are important in both wakefulness and cognition, projecting in large part to the forebrain where they play an important role in arousal.[7][8]

The lateral and dorsal pedunculopontine tegmentum contains primarily cholinergic neurons in neighboring groups within the midbrain and pons. Cholinergic neurons project to the thalamus and cortex, promoting desynchronization of the brain, allowing the body to switch from slow sleep rhythms to high frequency, low amplitude wake rhythms.[9]

Embryology

The neural tube, a derivative of the ectoderm, forms during the third week of embryogenesis. It splits into mesencephalon, prosencephalon, and rhombencephalon. The prosencephalon then further divides into the telencephalon and diencephalon. The thalamus and hypothalamus arise from the diencephalon. The mesencephalon, the central most of these structures, goes on to form the midbrain, while the rhombencephalon, the most caudal of these structures, forms both the metencephalon and the myelencephalon. The metencephalon is the precursor of the pons and cerebellum, while the myelencephalon gives rise to the medulla. Together, the pons, midbrain, and medulla contain the majority of constituents functioning within the reticular activating system, all of which were initially derived from the neural tube during embryogenesis.[10]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The RAS and its associated structures exist primarily within the hypothalamus and brainstem. The hypothalamus receives vascular perfusion mainly by branches of the circle of Willis, which sits inferiorly to the hypothalamus.

The brainstem is supplied primarily by branches of the basilar artery, which arises from the vertebral arteries. The caudal medulla receives blood supply from the anterior spinal artery medially and the posterior spinal artery laterally. Its more rostral portions are perfused by the posterior inferior cerebellar artery laterally and branches of the basilar artery medially.

Moving superiorly, the pons receives the majority of its blood supply from penetrating branches of the basilar artery. More laterally, it also receives vascular supply from branches of the anterior inferior cerebellar artery.

The midbrain, located rostral to the pons, primarily receives blood supply from branches of the posterior cerebral artery.[11]

Muscles

While the components of the reticular activating system are composed primarily of neural tissue, they do play an important role in the regulation of muscle tone in different states of sleep, as well as wakefulness. The thinking is that the RAS contributes to the suppression of muscle tone we experience during REM sleep, keeping us from moving our extremities during our dreams. The RAS may also play an important role in modulating muscle tone while awake, as it mediates arousal, and thus plays an important role in our "fight or flight" response to various threats.[12][13]

Surgical Considerations

Brainstem gliomas, as well as other tumors, may require neurosurgical removal. Research has found that the removal of tumors from regions around and/or inside of the brainstem can result in lesions affecting the function locus coeruleus, impairing REM sleep, and the functioning of the RAS. It is crucial to consider both the size and position of a tumor when contemplating the inherent risk of neurosurgery on areas proximal to the brainstem.[14]

Clinical Significance

The reticular activating system is thought to have a role in a variety of pathologies. Certain studies have suggested an affiliation between the RAS and the physiologic production of pain stimuli. In response to direct stimulation via electrodes, the reticular activating system has been shown to generate a pain response.[15]

The RAS has been further implicated in a variety of psychological disorders. Schizophrenic patients have been shown to have a statistically significant increase in the amount of pedunculopontine neurons, which are intricate in modifying the cholinergic component of the RAS.[16] Patients with both Parkinson disease and PTSD have been shown to have a decreased density of neurons in the locus coeruleus, which further affects the disinhibition of the pedunculopontine neurons.

Additionally, patients with Parkinson disease frequently have REM sleep disturbances. research suggests that the degeneration of the RAS contributes to the progression of Parkinson disease. Furthermore, narcolepsy, a disorder characterized by uncontrollable daytime sleepiness, is thought to be in part a result of major loss of orexin peptides, as well as the reduced output of pedunculopontine neurons.[16][17][18]

Media

References

Yeo SS, Chang PH, Jang SH. The ascending reticular activating system from pontine reticular formation to the thalamus in the human brain. Frontiers in human neuroscience. 2013:7():416. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00416. Epub 2013 Jul 25 [PubMed PMID: 23898258]

Garcia-Rill E, Kezunovic N, Hyde J, Simon C, Beck P, Urbano FJ. Coherence and frequency in the reticular activating system (RAS). Sleep medicine reviews. 2013 Jun:17(3):227-38. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2012.06.002. Epub 2012 Oct 6 [PubMed PMID: 23044219]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNishino S. Hypothalamus, hypocretins/orexin, and vigilance control. Handbook of clinical neurology. 2011:99():765-82. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-52007-4.00006-0. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21056227]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGiorgi FS, Ryskalin L, Ruffoli R, Biagioni F, Limanaqi F, Ferrucci M, Busceti CL, Bonuccelli U, Fornai F. The Neuroanatomy of the Reticular Nucleus Locus Coeruleus in Alzheimer's Disease. Frontiers in neuroanatomy. 2017:11():80. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2017.00080. Epub 2017 Sep 19 [PubMed PMID: 28974926]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSchwarz LA, Luo L. Organization of the locus coeruleus-norepinephrine system. Current biology : CB. 2015 Nov 2:25(21):R1051-R1056. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.09.039. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26528750]

Hornung JP. The human raphe nuclei and the serotonergic system. Journal of chemical neuroanatomy. 2003 Dec:26(4):331-43 [PubMed PMID: 14729135]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFujita A, Bonnavion P, Wilson MH, Mickelsen LE, Bloit J, de Lecea L, Jackson AC. Hypothalamic Tuberomammillary Nucleus Neurons: Electrophysiological Diversity and Essential Role in Arousal Stability. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2017 Sep 27:37(39):9574-9592. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0580-17.2017. Epub 2017 Sep 5 [PubMed PMID: 28874450]

Xie JF, Fan K, Wang C, Xie P, Hou M, Xin L, Cui GF, Wang LX, Shao YF, Hou YP. Inactivation of the Tuberomammillary Nucleus by GABA(A) Receptor Agonist Promotes Slow Wave Sleep in Freely Moving Rats and Histamine-Treated Rats. Neurochemical research. 2017 Aug:42(8):2314-2325. doi: 10.1007/s11064-017-2247-3. Epub 2017 Apr 1 [PubMed PMID: 28365867]

Vincent SR. The ascending reticular activating system--from aminergic neurons to nitric oxide. Journal of chemical neuroanatomy. 2000 Feb:18(1-2):23-30 [PubMed PMID: 10708916]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBressan M, Davis P, Timmer J, Herzlinger D, Mikawa T. Notochord-derived BMP antagonists inhibit endothelial cell generation and network formation. Developmental biology. 2009 Feb 1:326(1):101-11. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.10.045. Epub 2008 Nov 12 [PubMed PMID: 19041859]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDupont G, Schmidt C, Yilmaz E, Oskouian RJ, Macchi V, de Caro R, Tubbs RS. Our current understanding of the lymphatics of the brain and spinal cord. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2019 Jan:32(1):117-121. doi: 10.1002/ca.23308. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30362622]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLai YY, Siegel JM. Muscle tone suppression and stepping produced by stimulation of midbrain and rostral pontine reticular formation. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1990 Aug:10(8):2727-34 [PubMed PMID: 2388085]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTakakusaki K, Obara K, Nozu T, Okumura T. Modulatory effects of the GABAergic basal ganglia neurons on the PPN and the muscle tone inhibitory system in cats. Archives italiennes de biologie. 2011 Dec:149(4):385-405. doi: 10.4449/aib.v149i4.1383. Epub 2011 Dec 1 [PubMed PMID: 22205597]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSabbagh AJ, Alaqeel AM. Focal brainstem gliomas. Advances in intra-operative management. Neurosciences (Riyadh, Saudi Arabia). 2015 Apr:20(2):98-106. doi: 10.17712/nsj.2015.2.20140621. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25864061]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTaylor BK, Westlund KN. The noradrenergic locus coeruleus as a chronic pain generator. Journal of neuroscience research. 2017 Jun:95(6):1336-1346. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23956. Epub 2016 Sep 29 [PubMed PMID: 27685982]

Garcia-Rill E. Disorders of the reticular activating system. Medical hypotheses. 1997 Nov:49(5):379-87 [PubMed PMID: 9421802]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAnzak A, Tan H, Pogosyan A, Khan S, Javed S, Gill SS, Ashkan K, Akram H, Foltynie T, Limousin P, Zrinzo L, Green AL, Aziz T, Brown P. Subcortical evoked activity and motor enhancement in Parkinson's disease. Experimental neurology. 2016 Mar:277():19-26. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2015.12.004. Epub 2015 Dec 11 [PubMed PMID: 26687971]

Jang SH, Seo WS, Kwon HG. Post-traumatic narcolepsy and injury of the ascending reticular activating system. Sleep medicine. 2016 Jan:17():124-5. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2015.09.020. Epub 2015 Oct 27 [PubMed PMID: 26847985]