Introduction

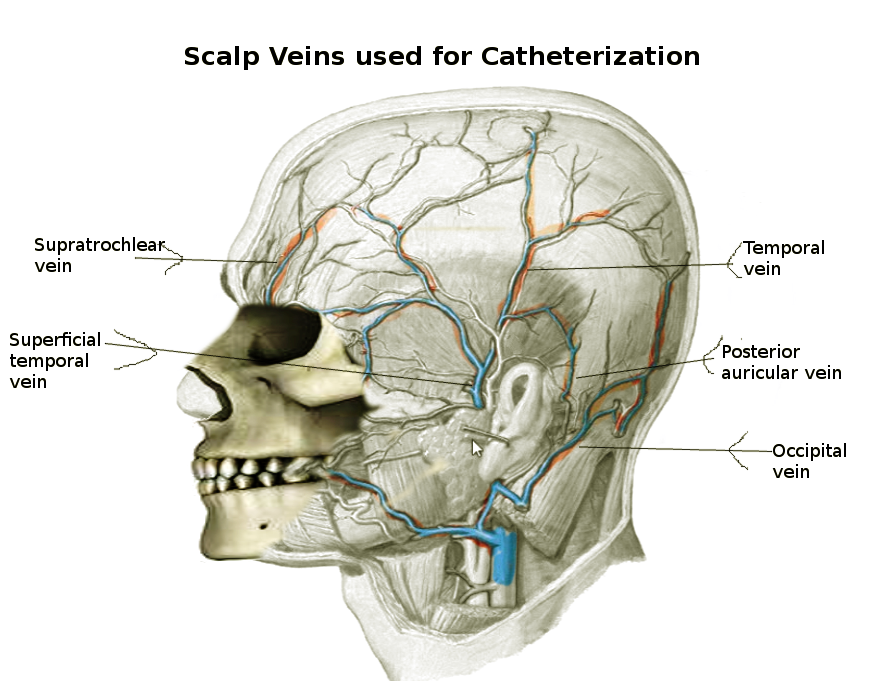

Peripheral venous access is a hallmark of resuscitation in patients of all ages. Ideal sites for venous catheterization are easy to access and pose the least risk to the patient. Sites for venous access in young children include the hands, feet, forearms, and scalp. The most common reasons for intravenous therapy in infants are to deliver maintenance fluids, blood and blood products, medications, and nutrition. The scalp veins are commonly used to secure access in neonates and infants, often after unsuccessful attempts at cannulation of upper and lower limb veins. Scalp veins offer ease of stabilization and access in this age group. Scalp veins in neonates and infants typically have less overlying subcutaneous fat than other peripheral sites to allow easier visualization and cannulation.[1][2][3] See Image. Scalp Veins Used for Catheterization.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

Scalp and facial veins are rather prominent in newborns and infants, are valveless, and are only thinly obscured by fine hair. The most commonly used veins include the superficial temporal, frontal (supratrochlear), occipital, and pre- and postauricular. The superficial temporal vein drains the entire lateral area of the scalp before passing inferiorly to join in the retromandibular vein's formation and then draining into the external jugular vein. The frontal and supratrochlear vein drains the anterior part of the scalp from the superciliary arches to the vertex, passes into the medial portion of the orbit to join the supraorbital vein in forming the angular vein (linked to cavernous sinus by ophthalmic veins), further draining into the facial and then into the internal jugular vein. The occipital vein drains the posterior aspect of the scalp, pierces the posterior neck musculature, and drains either directly into the internal jugular or the internal jugular vein via the posterior auricular. Lastly, the auricular veins run anteriorly and posteriorly to the ear, eventually draining into the external jugular vein.

Indications

Scalp vein cannulation is indicated in young patients requiring the administration of intravenous fluids or other medications, where peripheral intravenous access is not possible.

Contraindications

There is a relative contraindication for scalp vein cannulation placement in an older infant as there is a risk of easy dislodgement. Cannulation of scalp veins in areas with superficial skin lesions or evidence of infection should be avoided.

Equipment

The equipment needed for scalp cannulation includes:

- Choose the smallest catheter available (23-, 25-, or 27-G butterfly or scalp vein set) in the shortest length (typically 3/4 inch)

- 24-G catheter-over-needle may also be used but needs additional tubing

- Elastic band tourniquet

- Alcohol or other preoperative skin preparation

- Clear tape

- Clear adhesive bandage

- Saline flushes

- Clear plastic cup (optional)

Personnel

Scalp vein catheterization is usually performed by a doctor. However, a trained nurse with experience in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) can also perform scalp vein catheterization.

Preparation

Have another practitioner nearby to restrain the child during the procedure. Having a parent available to calm and comfort the child may also be helpful. A papoose or swaddling blanket may be helpful to restrain the patient's arms, especially if no assistance is available. The person placing the IV should be at the head of the bed for easier access to the scalp. One drop of oral sucrose or a pacifier may be placed on the infant's tongue to provide a calming effect.

Technique or Treatment

Veins are visible and can be distended by having the infant cry and using digital pressure at the base of the vein. Catheters should be directed toward the heart. The superficial temporal, frontal, occipital, and pre- and postauricular veins are suitable for use. It is important to differentiate between arteries and veins, as the scalp may have an impressive arterial network and a selection of veins. It can be difficult to tell the difference before the venipuncture is made. Any inadvertent arterial puncture must be followed by catheter removal and pressure to the site.

To further dilate the scalp veins, place a rubber or elastic band above the ears and eyes on the patient's scalp. Ensure the band is not too tight, as red or purplish skin indicates. Areas chosen behind the hairline may allow for a reduction in noticeable scars in the future. A nontortuous vein must be selected for catheterization. Clean the area with alcohol or preoperative skin preparation. Nearby areas of hair may be shaved to allow for better visualization and proper securing of the catheter. Pull gentle traction on the vein with the non-dominant hand to prevent movement of the vessel and proceed with inserting the needle. An obvious flashback of blood or "pop" when entering the vein may not be present when accessing younger children. Slowly and gently insert the needle parallel to the vessel at 20 to 30 degrees above the skin until you see blood in the chamber. The tourniquet may now be removed. Next, advance the needle slightly to confirm that the needle is in the vein. Allow the infant to calm down before threading the catheter. This mitigates venous spasms. Inject a small amount of saline solution to test the catheter's patency and position. If the saline flushes easily, without evidence of infiltration, the catheter should be secured. Place a small piece of rolled gauze under the catheter hub to prevent pressure on the underlying skin. Apply transparent adhesive dressing to the hub site, then adhere several pieces of tape in a crisscross or "H" pattern to secure the device. Also, tape a loop of the loose tubing nearby so that, if pulled on, the loop can give way before the catheter. Some references recommend taping down a half-cut, clear plastic cup over the site for further protection. The base of the cup may be cut to form a hinge for easier access.

Complications

Venous dural sinus air embolism is an inherent risk due to the valveless nature of scalp veins. Injecting air into the scalp vein catheter and leaving it open to air when the infant is in a head-up tilt position must be avoided. Preventative measures include a supine or Trendelenburg position during daily catheter management. An air occlusive dressing should be used once the catheter is removed.[3][4][5]

Puncture site infection may occur if the area is not cleaned properly before needle insertion or if the needle is left in place for an extended period. Research shows that peripheral intravenous delivery in children may have a longer duration until bacterial colonization than in adults. This may be up to 6 days. A peripherally inserted venous catheter may be considered if intravenous access is needed for more than 1 week.

Scalp vein needles provide a lesser risk of infection compared with plastic catheters. Teflon catheters have the highest rate of phlebitis. Other potential complications include rare scalp abscesses, alopecia, intracranial abscess, thrombophlebitis, and scalp necrotizing fasciitis.[6][7][8]

Clinical Significance

Scalp veins can be used for peripherally inserted venous catheters without increased complications compared to other insertion sites.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Scalp vein catheterization can be a lifesaving measure in infants who lack peripheral access. The anesthesiologist or the NICU staff does the catheterization in most cases. However, the monitoring of these lines is usually performed by NICU nurses. However, nurses need to know the potential complications of these lines, which can range from an air embolus to dural sinus thrombosis and infection. The line insertion site must be regularly cleaned and monitored for infection. Overall, the durability of scalp vein catheterization is much shorter than that of peripheral lines. In most cases, the scalp line is removed when peripheral access is obtained.[9]

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

Scalp vein catheterization is usually performed by pediatricians or neonatologists. However, nurses trained in the NICU are required to know the procedure and its complications. During the maintenance of a scalp vein catheter, it is important that the nurses inspect the site daily and clean it with antiseptics. The child in whom scalp vein catheterization is performed must be nursed in a Trendelenburg position. It must also be ensured that the hub of the catheter is not kept open and there is no air inside the tubing.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Scalp Veins Used for Catheterization. Common reasons for intravenous therapy in infants are to deliver maintenance fluids, blood and blood products, medications, and nutrition. Scalp veins are also used to secure access in neonates and infants, often after unsuccessful attempts at cannulation of upper and lower limb veins.

Contributed by S Bhimji, MD

References

Bashir RA, Callejas AM, Osiovich HC, Ting JY. Percutaneously Inserted Central Catheter-Related Pleural Effusion in a Level III Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: A 5-Year Review (2008-2012). JPEN. Journal of parenteral and enteral nutrition. 2017 Sep:41(7):1234-1239. doi: 10.1177/0148607116644714. Epub 2016 Apr 15 [PubMed PMID: 27084698]

Callejas A, Osiovich H, Ting JY. Use of peripherally inserted central catheters (PICC) via scalp veins in neonates. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine : the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstetricians. 2016 Nov:29(21):3434-8. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2016.1139567. Epub 2016 Mar 7 [PubMed PMID: 26754595]

Fortrat JO, Saumet M, Savagner C, Leblanc M, Bouderlique C. Bubbles in the brain veins as a complication of daily management of a scalp vein catheter. American journal of perinatology. 2005 Oct:22(7):361-3 [PubMed PMID: 16215922]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMeguro T, Terada K, Hirotsune N, Nishino S, Asano T. Postoperative extradural hematoma after removal of a subgaleal drainage catheter--case report. Neurologia medico-chirurgica. 2007 Jul:47(7):314-6 [PubMed PMID: 17652918]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAl-Hathlol K, Al-Mane K, Al-Hathal M, Al-Tawil K, Abulaimoun B. Air emboli in the intracranial venous sinuses of neonates. American journal of perinatology. 2002 Jan:19(1):55-8 [PubMed PMID: 11857097]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFernández LM, Domínguez J, Callejón A, López S, Pérez-Avila A, Martín V. [Intracranial epidural abscess in a newborn secondary to skin catheter]. Neurocirugia (Asturias, Spain). 2001 Aug:12(4):338-41 [PubMed PMID: 11706679]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAlli NA, Wainwright RD, Mackinnon D, Poyiadjis S, Naidu G. Skull bone infarctive crisis and deep vein thrombosis in homozygous sickle cell disease- case report and review of the literature. Hematology (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2007 Apr:12(2):169-74 [PubMed PMID: 17454200]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBrook J, Moss E. Air in the cavernous sinus following scalp vein cannulation. Anaesthesia. 1994 Mar:49(3):219-20 [PubMed PMID: 8147514]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLeick-Rude MK, Haney B. Midline catheter use in the intensive care nursery. Neonatal network : NN. 2006 May-Jun:25(3):189-99 [PubMed PMID: 16749374]