Introduction

Scheuermann kyphosis, also known as Scheuermann disease, juvenile kyphosis, or juvenile discogenic disease, is a condition of hyperkyphosis that involves the vertebral bodies and discs of the spine identified by anterior wedging of greater than or equal to 5 degrees in 3 or more adjacent vertebral bodies. The thoracic spine is most commonly involved, although involvement can include the thoracolumbar/lumbar region as well [1].

Most commonly, diagnosis is made in adolescents aged 12 to 17 years who present after their parents notice a postural deformity or “hunchbacked” appearance. Pain in the affected hyperkyphotic region may also be the cause of initial evaluation [2].

There is a hereditary component associated with this condition, although the exact mode of transmission is still unclear. This is supported by the fact that incidence is higher in monozygotic versus dizygotic twins [1].

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Definitive and universally accepted etiology of Scheuermann kyphosis remains undetermined. As previously mentioned, a hereditary component is understood to contribute to this condition's development, although the mode of transmission is still unclear.

One growing theory, supported by histologic findings, suggests discordant vertebral endplate mineralization and ossification during growth which causes disproportional vertebral body growth and resultant classic wedge-shaped vertebral bodies that lead to kyphosis [3].

Epidemiology

- Prevalence: 1% to 8% in the United States [4][1]

- Sex: Male to female ratio is at least 2:1

- Age: Most commonly diagnosed in adolescents 12-17 years

- Rarely diagnosed in children less than 10 years.

- Classification: Type I (Classic) - Thoracic spine involvement only, with the apex of curve T7-T9Type II - Thoracic and lumbar involvement, with the apex of curve T10-T12

Pathophysiology

The exact pathophysiology as it relates to Scheuermann kyphosis is still undetermined. Likely, genetic inheritance results in discordant vertebral endplate mineralization and ossification during growth, causing disproportional vertebral body growth with the resultant classic wedge-shaped vertebral bodies that lead to kyphosis [5][6].

Suggested components that might explain or partially explain this condition, among many others, include abnormal collagen to proteoglycan ratios, dural cysts, childhood osteoporosis, biomechanical stressors such as tight hamstrings, and growth hormone hypersecretion.

The most common findings associated with this disease include thoracic spine hyperkyphosis as defined by the diagnostic criteria commonly associated with irregular vertebral endplates, Schmorl nodes, and loss of disc space height noted on sagittal imaging studies [3].

Histopathology

- Abnormal vertebral endplate cartilage [6]

- Irregular mineralization

- Altered endochondral ossification

- Decreased collagen to proteoglycan ratios (i.e., increased proteoglycan levels)

History and Physical

The adolescent will present with (1) cosmetic/postural deformity and/or (2) subacute thoracic pain. The deformity is typically appreciated in the early-mid teenage years by the child, parents, or on a school screening exam. With respect to subacute thoracic pain, there is usually no identifiable inciting event. The pain is worse with activity and improved with rest.

Physical exam shows rigid hyperkyphotic curve, accentuated with forward bending. The hyperkyphosis does not resolve with an extension or lying prone/supine, further supporting the “rigid” nature of this deformity. Other associated findings on an exam might include cervical or lumbar hyperlordosis, scoliosis, and tight hamstrings. Although neurologic deficits are uncommon, a thorough neurologic exam must be completed [2][4].

At each visit, the patient’s spinal range of motion should be evaluated in all planes of motion: flexion/extension, right/left lateral bending, and right/left rotation. The degree of hyperkyphosis should also be followed over time via serial imaging to assess the degree of progression. Tracking the patient’s functional range of motion as well as the degree of deformity will help guide the appropriate intervention and prognosis.

Evaluation

History and physical along with AP/lateral radiographs comprise the essential components for evaluating Scheuermann kyphosis. Lateral radiographs are required for diagnosis and diagnostic criteria include the following [4]:

-

Rigid hyperkyphosis, greater than 40 degrees

-

Anterior wedging, greater than or equal to 5 degrees in three or more adjacent vertebral bodies

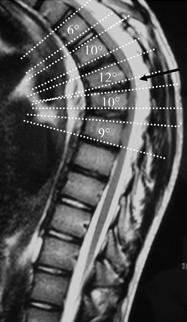

Technique for Determining Degree of Kyphosis on Lateral Imaging [3][4]

-

The line is drawn along the superior endplate of the most tilted vertebrae on the cephalad portion of the kyphotic curve

-

The line is drawn along the inferior endplate of the most tilted vertebrae on the caudal portion of the kyphotic curve

-

The angle formed by the intersection of lines perpendicular to the above-described lines is the measured Cobb angle

-

Hyperkyphosis is described as measured Cobb angle greater than 40 degrees

Technique for Determining Degree of Anterior Wedging on Lateral Imaging [3][4]

-

The line is drawn from posterior to anterior along the superior endplate

-

The line is drawn from posterior to anterior along the inferior endplate

-

The angle formed by the intersection of these lines anteriorly is the measured Wedge angle

-

Anterior wedging of greater than or equal to 5 degrees in three or more adjacent vertebral bodies, with an associated rigid hyperkyphosis greater than 40 degrees, is diagnostic for Scheuermann disease

Other Associated Findings Noted on AP/Lateral Radiographs [3][4]

-

Irregular vertebral endplates

-

Schmorl nodes

-

Loss of disc space height

-

Scoliosis

-

Spondylolysis/spondylolisthesis

-

Disc herniation

Although typically not a necessity, MRI can be helpful to further evaluate anatomic changes or for pre-operative planning. CT imaging is usually not needed. There are also no specific laboratory tests or histologic findings necessary for the diagnosis of Scheuermann kyphosis.

Treatment / Management

Nonoperative Management [1][7]

- Stretching, lifestyle modification, NSAIDs, plus/minus physical therapy

-

Indication

- Kyphosis less than 60 degrees and asymptomatic

-

Course

-

The majority of patients fall into this category

-

Patients typically do well without significant long-term sequelae

-

Extension bracing plus “A”

-

Indication

-

Kyphosis 60 to 80 degrees plus/minus symptomatic

-

Course

-

Bracing is typically required for 12 to 24 months

-

Most effective in skeletally immature patients

-

Typically, does not improve the curve but rather impedes progression

-

Braces [8]

-

Milwaukee brace

-

Kyphologic brace

-

Thoracolumbosacral orthosis-style Boston brace

-

Spinal fusion is typically a combination of anterior release + fusion as well as posterior instrumentation + fusion

-

Indications

-

Kyphosis greater than 75 degrees causing unacceptable deformity

-

Kyphosis greater than 75 degrees with associated pain

-

Neurologic deficit/spinal cord compression

-

Severe refractory pain

-

Course

-

The majority of patients experience symptomatic improvement as well as improved curve deformity toward normal

-

Operative/postoperative complications must be considered

Differential Diagnosis

- Postural kyphosis (flexible postural deformity)

- Hyperkyphosis attributable to another known disease state

- Postsurgical kyphosis

- Ankylosing spondylitis

- Scoliosis

Prognosis

The majority of patients are successfully treated with conservative measures, as previously discussed [2]. Pain in the affected region typically improves after skeletal maturity is reached, although patients with Scheuermann kyphosis are at increased risk of chronic back pain as compared to the general population. Long-term follow-up studies typically suggest a lower health-related quality of life and increased back pain in adulthood.

Patients with a kyphotic curve less than 60 degrees at skeletal maturity typically have no long-term sequelae.

Complications

Potential complications

- Progressive cosmetic deformity

- Chronic back pain

- Neurologic deficits/spinal cord compression

Postoperative complications

- Pseudoarthrosis (most common complication)

- Persistent pain

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

For surgical patients, inpatient rehabilitation might be necessary for mobility and strength training as well as aggressive postoperative pain management.

Consultations

Although not always a necessity, it is good practice for any patient with some degree of suspected spinal deformity to establish care with either an orthopedic spine surgeon or neurosurgeon.

Neurosurgery or orthopedic spine surgery consultation should be obtained for any patient with the following:

- Hyperkyphosis unresponsive to conservative management

- Any neurologic deficit

- Patients with compromised pulmonary function testing attributable to their kyphosis

Deterrence and Patient Education

Important patient education includes [9]:

- Extension-based stretching/strengthening program

- Hamstring stretching exercise program

- Proper postural and body mechanic techniques for ADLs

- Appropriate use and handling of braces

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Although the overall prognosis of this disease is relatively good, given young patients are most commonly affected, it is important and medically prudent to notify the patient and family members early in their course of care of the potential for long-term sequela and the unpredictable nature of things such as chronic back pain associated with the condition.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Palazzo C, Sailhan F, Revel M. Scheuermann's disease: an update. Joint bone spine. 2014 May:81(3):209-14. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2013.11.012. Epub 2014 Jan 24 [PubMed PMID: 24468666]

Tomé-Bermejo F, Tsirikos AI. [Current concepts on Scheuermann kyphosis: clinical presentation, diagnosis and controversies around treatment]. Revista espanola de cirugia ortopedica y traumatologia. 2012 Nov-Dec:56(6):491-505. doi: 10.1016/j.recot.2012.07.002. Epub 2012 Sep 1 [PubMed PMID: 23594948]

Aufdermaur M. Juvenile kyphosis (Scheuermann's disease): radiography, histology, and pathogenesis. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 1981 Jan-Feb:(154):166-74 [PubMed PMID: 7471550]

Makurthou AA, Oei L, El Saddy S, Breda SJ, Castaño-Betancourt MC, Hofman A, van Meurs JB, Uitterlinden AG, Rivadeneira F, Oei EH. Scheuermann disease: evaluation of radiological criteria and population prevalence. Spine. 2013 Sep 1:38(19):1690-4. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31829ee8b7. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24509552]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHalal F, Gledhill RB, Fraser C. Dominant inheritance of Scheuermann's juvenile kyphosis. American journal of diseases of children (1960). 1978 Nov:132(11):1105-7 [PubMed PMID: 717319]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceZaidman AM, Zaidman MN, Strokova EL, Korel AV, Kalashnikova EV, Rusova TV, Mikhailovsky MV. The mode of inheritance of Scheuermann's disease. BioMed research international. 2013:2013():973716. doi: 10.1155/2013/973716. Epub 2013 Sep 12 [PubMed PMID: 24102061]

Patel DR, Kinsella E. Evaluation and management of lower back pain in young athletes. Translational pediatrics. 2017 Jul:6(3):225-235. doi: 10.21037/tp.2017.06.01. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28795014]

Weiss HR, Turnbull D, Bohr S. Brace treatment for patients with Scheuermann's disease - a review of the literature and first experiences with a new brace design. Scoliosis. 2009 Sep 29:4():22. doi: 10.1186/1748-7161-4-22. Epub 2009 Sep 29 [PubMed PMID: 19788753]

Pizzutillo PD. Nonsurgical treatment of kyphosis. Instructional course lectures. 2004:53():485-91 [PubMed PMID: 15116637]