Introduction

Schistosomiasis is a parasitic disease historically known as bilharzia caused by the trematode of the genus Schistosoma. Estimates place the affected worldwide population for all forms of schistosomiasis at 230 million, with an estimated 700 million at risk.[1] 3 primary species of schistosomes affects human, Schistosoma japonicum, S. haematobium, and S. mansoni. These species are primarily responsible for the 2 major forms of schistosomiasis, intestinal and urogenital.[2]

Schistosoma haematobium causes urogenital schistosomiasis (UGS). Its name is derived from hematuria or bloody urine. It is a recognized carcinogen and the 2nd leading cause of bladder cancer worldwide. It is also an underdiagnosed cause of infertility and predisposes chronically infected individuals to HIV.[3][4]

Schistosoma haematobium is prevalent in regions of Africa and the Middle East. The lifecycle of schistosomes is complex and involves both snail and human hosts. Spread is perpetuated by contact with affected water in endemic areas, making control and eradication difficult to achieve.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Schistosoma haematobium is a trematode of the genus Schistosoma. It belongs to the trematode order Diplostomida in the subclass Digenea.

It is a parasitic flatworm (commonly known as a blood fluke) that parasitizes the venous plexus of the bladder and other urogenital organs. The lifecycle is complex and involves an intermediate host, primarily freshwater snails belonging to the genus Bulinus, and primary host, typically a human. Distribution of schistosomiasis is defined by the specific host snail species habitat range.[2]

Epidemiology

Per the World Health Organization (WHO), 78 countries have reported transmission of schistosomiasis in all forms, and it is endemic in 52. The WHO Global Health Estimates from 2016 estimated that schistosomiasis had a death rate of 0.3 per 100,000. There were also estimated to be 24,000 deaths in 2016, which decreased from 55,000 in 2000.

Schistosoma haematobium is the species responsible for urogenital schistosomiasis. It is endemic to many countries in sub-Saharan Africa, as well as some parts of the Middle East. It is especially prevalent in tropical and subtropical areas, particularly affecting communities that lack access to sanitation and safe drinking water.[5]

The most prevalent form of urogenital schistosomiasis is chronic. While acute schistosomiasis (or Katayama fever) can be caused by S. haematobium, it is more recognized in other schistosome species. In endemic areas, the average age of initial infection is age 2, with an increasing worm burden for the next 10 years. Infection intensity and prevalence in a region of Kenya were highest in children aged 5 to 14 years old. Infection prevalence and intensity are possibly due to the frequency of contact with water during daily activities, as adult individuals with high water contact during their daily activities (fishing, laundry, etc.) have also been shown to have persistence of prevalence and infection.[6][7]

Serology has shown that endemic areas have almost a 100% infection rate, with 60% to 80% of school-age children and 20% to 40% of adults remaining actively infected.[7]

In endemic regions, up to 65% of patients with bladder cancer (typically squamous cell carcinoma) had concomitant urogenital schistosomiasis.[4]

Pathophysiology

Schistosoma haematobium eggs are excreted from the human host via urine into freshwater. Each egg contains a mature ciliated form, known as a miracidium. Upon contacting freshwater, the egg hatches and releases the miracidium, which can penetrate the soft tissue of its intermediate host, the Bulinus snail.

In the intermediate snail host, the schistosome undergoes asexual reproduction through sporocyst stages and, after 4 to 6 weeks, sheds thousands of infectious cercariae into the water. Cercariae penetrate the skin of the mammalian host. The larvae (termed schistosomula at that point) then require approximately 10 to 12 weeks to reach maturation and produce eggs within the host. Unlike many other schistosome species, S. haematobium relies primarily on a human host, which aids in control efforts.[8][9][10]

Adult worms of the species S. haematobium live within the urogenital venules, where they primarily digest erythrocytes. The involvement of the urogenital organs varies markedly and correlates with vascularity; with the bladder, lower ureters, urethra, seminal vesicles, uterus, vagina, and cervix most commonly affected. Unlike other schistosomes that live within the mesenteric venules and release their eggs into the host’s intestines, S. haematobium releases its eggs into the urinary tract. Therefore their eggs are excreted via the host’s urine.[7][11]

Up to half of the thousands of eggs that are released throughout the adult trematodes average lifespan of 3 to 7 years (ranging from 20 to 290 eggs per day in S. haematobium) are not excreted, but instead, become lodged in the urogenital system. This is the primary mechanism of chronic sequelae from infection as the eggs induce a granulomatous host response and subsequent tissue inflammation.[10]

History and Physical

Any individual that lives in or has traveled to an endemic area should be considered for urogenital schistosomiasis if they present with a variety of symptoms to include dysuria, painful hematuria, urinary obstruction, vaginal discharge, or pain/bleeding after intercourse. Gross hematuria typically occurs at the end of voiding, termed terminal hematuria. Men may also experience hematospermia.[2]

Although acute schistosomiasis is less common with S. haematobium compared to other species, it will occur more frequently in nonimmune travelers. Symptoms are generally non-specific: gastrointestinal symptoms, fever, fatigue, or respiratory symptoms. Screening all returning travelers from endemic areas should be considered as approximately 25% of asymptomatic individuals developed chronic schistosomiasis in one study.[5]

If the individual remains untreated for approximately 3 to 4 months, he or she can present with dysuria or hematuria due to ulcerations and inflammation within the bladder and urogenital tract. Continued disease burden and egg deposits can cause polyps, nodules, and “sandy patches” to become visible during cystoscopy and colposcopy. “Sandy patches” are when the calcified schistosome ova within atrophied mucosa appear like sand. Progression can lead to fibrosis and calcification of the bladder wall, causing obstruction, bacteriuria, and bladder cancer.[12][10]

Because worms do not reproduce in the human host, the burden of infection is dependent on repeated exposures and the number of cercariae encountered in exposures. Women that are responsible for domestic chores such as washing clothes in endemic waters are susceptible to increased infection rates and disease burden.

Genital tract involvement will occur in up to 75% of women affected by S. haematobium, termed female genital schistosomiasis (FGS). FGS is caused by schistosome egg deposits in the genital tract causing mucosal bleeding, abnormal blood vessels, and “sandy patches” on the vulva, perineum, or cervix. In women of child-bearing age, it is a common cause of spontaneous abortion, ectopic pregnancy, dysmenorrhea, and intermenstrual bleeding, as well as low gestational birth weight and poor birth-outcomes due to placental inflammation and infection. Due to the lesions and inflammation, women and men with urogenital schistosomiasis are also more susceptible to HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs).[13][14][10]

Evaluation

Simple urinalysis or urine dip can be used to identify those at risk of urogenital schistosomiasis. Diagnosis can be made by microscopic examination of urine for eggs, although this has low overall sensitivity due to daily fluctuation in egg output. Serology can be performed with variable sensitivity ranging from 41% to 78%. Serology and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) can be useful for symptomatic travelers or those presenting with symptoms of acute schistosomiasis, although it is less useful in endemic areas due to the inability to discriminate between active infection and prior exposure. Multimodal laboratory testing to include urine dipstick, complete blood count, and serology are more effective when utilized in tandem. There is no current laboratory gold standard to identify the worm burden, which makes cost-efficient treatment and management more difficult.[15][16][17][18]

Microscopic examination of eggs will show a relatively large oval-shaped structure that measures 110 to 170 micrometers long by 40 to 70 micrometers wide. These eggs are notable for a terminal spine, and this is in contrast to S. mansoni and S. japonicum eggs, which exhibit a lateral spine and lateral knob, respectively.[19]

Multiple imaging modalities can be useful in diagnosis, including ultrasonography, radiography, IV pyelogram, cystoscopy, and colposcopy. Ultrasound of the genitourinary tract is becoming the imaging gold standard in quantifying the burden of disease, although it is resource utilization heavy. It may show bladder wall irregularities due to underlying granulomas, as well as hydronephrosis, bladder polyps, and tumors. Radiographic imaging with a standard KUB view may show characteristic calcifications due to long-standing bladder wall fibrosis. Computed tomography can also be useful in identification.[20][21][10]

Women with female genital schistosomiasis (FGS) often present with symptoms of STI or infertility and are incorrectly diagnosed and treated. Per the WHO, this is primarily due to a general lack of awareness of FGS by healthcare professionals. FGS can be diagnosed via speculum exam and visual inspection of the cervix and vagina for characteristics lesions such as “sandy patches,” hypervascularity, and tissue friability. Colposcopy and camera can improve visualization.[14][7]

Evaluating the distribution of Bulinus snails and the prevalence of S. haematobium with PCR within these snails can be useful in mapping and monitoring areas of higher prevalence. Furthermore, this can be useful in monitoring transmission to areas of low prevalence.[22]

Treatment / Management

The recommended treatment for schistosomiasis is the anthelminthic praziquantel, dosing regimens vary:

- 40 mg/kg given as a single dose,

or

- 20 mg/kg every 4-6 hours for three doses

Praziquantel in these dosages effectively kills adult worms and prevents the release of eggs and the development of new urogenital lesions. As it is primarily effective against adult worms, treatment is best initiated at least four to six weeks post-exposure.[23][24][25](A1)

While some resistance has been noted in other species of Schistosoma, it has been minimal in S. haematobium. Praziquantel is generally safe in pregnancy, rated category B.

If there is one documented case of urogenital schistosomiasis, there are likely many other individuals that use the same water source that are affected. Mass treatment regimens have been undertaken in multiple communities and countries with significant success. In 1997, Egypt launched a Praziquantel mass treatment program. Before treatment, the studied villages had prevalence ranging from greater than 30% to 10% to 20%; following treatment prevalence had decreased to less than 3% in the vast majority.[26]

Differential Diagnosis

- Urinary tract infection

- Glomerulonephritis

- Sexually transmitted infections (to include gonorrhea, chlamydia, HSV, etc.)

- Urogenital cancer

- Other causes of infertility

- Epididymitis

- Other parasitic infections such as S. mansoni and S. japonicum, clonorchiasis and trichinosis

- Renal tuberculosis

Prognosis

In early chronic infection, proper administration of praziquantel can alleviate symptoms and minimize long term inflammation and granuloma formation. However, urogenital lesions are often only partially reversible depending on the degree and type of tissue damage. Sequalae of these lesions can also be chronic.

After treatment with praziquantel, a study of 527 women found no significant reduction in the “sandy patches” seen on colposcopy following treatment. Symptoms to include contact bleeding and vessel abnormalities also remained.[14]

Prognosis also depends on the likelihood of reexposure and the need for subsequent treatment.

Complications

As previously detailed, complications can include female infertility and spontaneous abortion, increased incidence of STIs to include HIV, urinary tract obstruction potentially leading to chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease, and bladder cancer.

Bladder cancer related to chronic UGS is the most common squamous cell carcinoma, in comparison to transitional cell carcinoma that is the most common type of bladder cancer overall. The etiology is multifactorial and includes chronic irritation and inflammation, restorative hyperplasia, and subsequent DNA and tissue damage.

Individuals with schistosomiasis, including from S. haematobium, are also more susceptible to Salmonella typhi and other Salmonella species causing prolonged bacteremia. Chronic inflammation can also lead to many subsequent issues to include anemia of chronic disease, malnutrition, and stunting of growth in children.[27]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Schistosomiasis is a disease that disproportionally affects those with poor hygiene, lack of healthcare resources, and poor living and working conditions overall. Lack of proper education regarding its prevalence and symptoms also impedes recognition and treatment. Population education regarding limiting urination into fresh-water lakes would also be beneficial as there is a short window for miracidia to infect snails.

Overall, elimination efforts would likely need to be multifactorial involving education and mass treatment programs. Unfortunately, it would also require significant cost and time investments by endemic countries, many of which are poverty-stricken.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Urogenital Schistosomiasis is an endemic disease causing a variety of chronic issues in millions of people in Africa and the Middle East. It is easily treatable with praziquantel if there is a high index of suspicion, particularly in endemic areas. The WHO has several easily accessible resources for healthcare providers to utilize in the diagnosis and treatment of UGS and FGS. One such resource is the WHO Pocket Atlas for FGS, available on their website.

Healthcare providers in non-endemic countries must also remember to consider Schistosomiasis in the evaluation and treatment of individuals presenting with acute or chronic symptoms who have previously traveled to endemic countries.

Healthcare professional and organizational initiation of community or school-wide mass treatment programs in endemic areas would considerably reduce disease burden. Mass treatment of urogenital Schistosomiasis may also be a cost-effective way to reduce HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa.[28]

Media

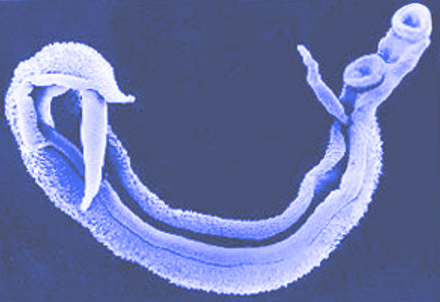

(Click Image to Enlarge)

This photomicrograph reveals ultrastructural details exhibited by a single Schistosoma japonicum ovum. S. japonicum is one of the trematodes that causes the parasitic disease schistosomiasis. Its egg displays a vestigial, laterally protruding spine, which is more of a remnant of a spine than a distinct spine. Schistosomiasis infections are diagnosed when the presence of their eggs in the urine or stool sample is confirmed. Contributed by the CDC

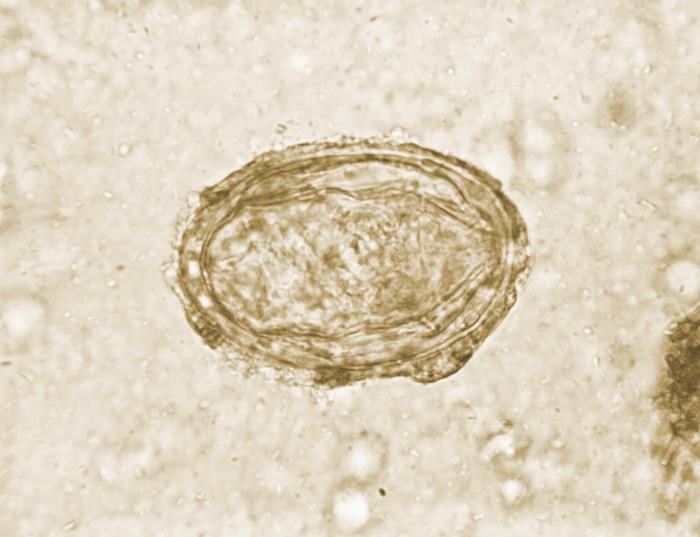

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Schistosomiasis Infection. Under a magnification of 500X, this photomicrograph of a liver tissue specimen revealed signs of a schistosomiasis infection. This included a histopathologic finding known as pipe stem cirrhosis, which occurs when schistosomes infect the liver, known as hepatic schistosomiasis. The ensuing scarring entraps these parasites and their ova in and around the hepatic portal circulatory vessels.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

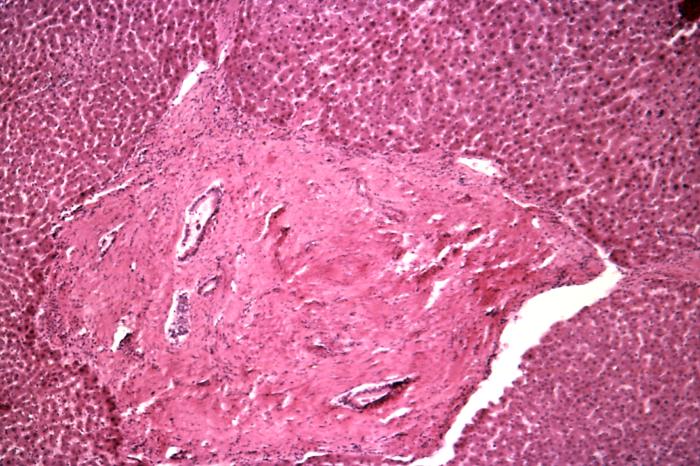

(Click Image to Enlarge)

This photomicrograph depicts some of the histopathologic details seen in a bladder tissue specimen, in a case of schistosomiasis haematobium, also known as urinary blood fluke, caused by the parasitic flatworm, Schistosoma haematobium. Note the presence of clusters of S. haematobium ova, surrounded by intense eosinophilic infiltrates, and other inflammatory cells. For another view of this condition, at a lesser magnification, see PHIL 34. Contributed by the CDC/ Dr. Edwin P. Ewing, Jr.

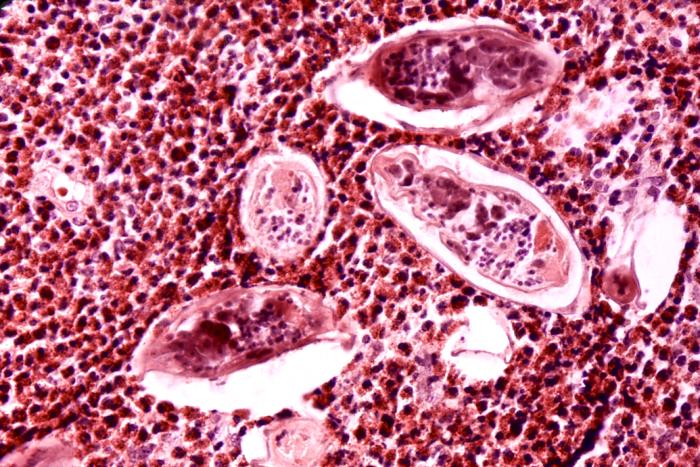

(Click Image to Enlarge)

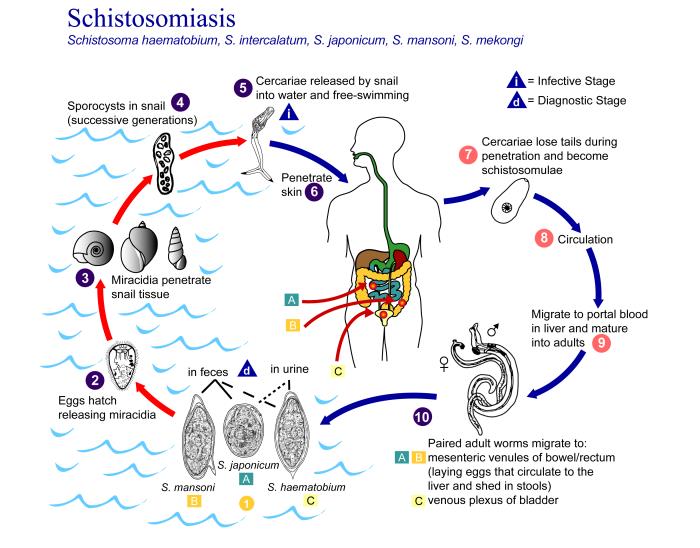

This is an illustration depicting the life cycle of flatworms of the genus, Schistosoma, the causal agents of the parasitic disease schistosomiasis. For a complete description of the Schistosoma haematobium, S. intercalatum, S. japonicum, S. mansoni, S. mekongi life cycle, paste the following address in your address bar: https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/schistosomiasis/index.html. Contributed by the CDC/ Alexander J. da Silva, PhD; Melanie Moser

References

Tan SY, Ahana A. Theodor Bilharz (1825-1862): discoverer of schistosomiasis. Singapore medical journal. 2007 Mar:48(3):184-5 [PubMed PMID: 17342284]

Gryseels B, Polman K, Clerinx J, Kestens L. Human schistosomiasis. Lancet (London, England). 2006 Sep 23:368(9541):1106-18 [PubMed PMID: 16997665]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAntoni S, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Znaor A, Jemal A, Bray F. Bladder Cancer Incidence and Mortality: A Global Overview and Recent Trends. European urology. 2017 Jan:71(1):96-108. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.06.010. Epub 2016 Jun 28 [PubMed PMID: 27370177]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencevan Tong H, Brindley PJ, Meyer CG, Velavan TP. Parasite Infection, Carcinogenesis and Human Malignancy. EBioMedicine. 2017 Feb:15():12-23. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.11.034. Epub 2016 Dec 2 [PubMed PMID: 27956028]

Nicolls DJ, Weld LH, Schwartz E, Reed C, von Sonnenburg F, Freedman DO, Kozarsky PE, GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Characteristics of schistosomiasis in travelers reported to the GeoSentinel Surveillance Network 1997-2008. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene. 2008 Nov:79(5):729-34 [PubMed PMID: 18981513]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKing CH, Keating CE, Muruka JF, Ouma JH, Houser H, Siongok TK, Mahmoud AA. Urinary tract morbidity in schistosomiasis haematobia: associations with age and intensity of infection in an endemic area of Coast Province, Kenya. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene. 1988 Oct:39(4):361-8 [PubMed PMID: 3142286]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceColley DG, Bustinduy AL, Secor WE, King CH. Human schistosomiasis. Lancet (London, England). 2014 Jun 28:383(9936):2253-64. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61949-2. Epub 2014 Apr 1 [PubMed PMID: 24698483]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHe YX, Salafsky B, Ramaswamy K. Comparison of skin invasion among three major species of Schistosoma. Trends in parasitology. 2005 May:21(5):201-3 [PubMed PMID: 15837605]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceInobaya MT, Olveda RM, Chau TN, Olveda DU, Ross AG. Prevention and control of schistosomiasis: a current perspective. Research and reports in tropical medicine. 2014 Oct 17:2014(5):65-75 [PubMed PMID: 25400499]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTzanetou K, Adamis G, Andipa E, Zorzos C, Ntoumas K, Armenis K, Kontogeorgos G, Malamou-Lada E, Gargalianos P. Urinary tract Schistosoma haematobium infection: a case report. Journal of travel medicine. 2007 Sep-Oct:14(5):334-7 [PubMed PMID: 17883465]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGhoneim MA. Bilharziasis of the genitourinary tract. BJU international. 2002 Mar:89 Suppl 1():22-30 [PubMed PMID: 11876729]

Khalaf I, Shokeir A, Shalaby M. Urologic complications of genitourinary schistosomiasis. World journal of urology. 2012 Feb:30(1):31-8. doi: 10.1007/s00345-011-0751-7. Epub 2011 Sep 10 [PubMed PMID: 21909645]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMbabazi PS, Andan O, Fitzgerald DW, Chitsulo L, Engels D, Downs JA. Examining the relationship between urogenital schistosomiasis and HIV infection. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2011 Dec:5(12):e1396. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001396. Epub 2011 Dec 6 [PubMed PMID: 22163056]

Kjetland EF, Mduluza T, Ndhlovu PD, Gomo E, Gwanzura L, Midzi N, Mason PR, Friis H, Gundersen SG. Genital schistosomiasis in women: a clinical 12-month in vivo study following treatment with praziquantel. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2006 Aug:100(8):740-52 [PubMed PMID: 16406034]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTsang VC, Wilkins PP. Immunodiagnosis of schistosomiasis. Immunological investigations. 1997 Jan-Feb:26(1-2):175-88 [PubMed PMID: 9037622]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKinkel HF, Dittrich S, Bäumer B, Weitzel T. Evaluation of eight serological tests for diagnosis of imported schistosomiasis. Clinical and vaccine immunology : CVI. 2012 Jun:19(6):948-53. doi: 10.1128/CVI.05680-11. Epub 2012 Mar 21 [PubMed PMID: 22441394]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDe Vlas SJ, Engels D, Rabello AL, Oostburg BF, Van Lieshout L, Polderman AM, Van Oortmarssen GJ, Habbema JD, Gryseels B. Validation of a chart to estimate true Schistosoma mansoni prevalences from simple egg counts. Parasitology. 1997 Feb:114 ( Pt 2)():113-21 [PubMed PMID: 9051920]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWhitty CJ, Mabey DC, Armstrong M, Wright SG, Chiodini PL. Presentation and outcome of 1107 cases of schistosomiasis from Africa diagnosed in a non-endemic country. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2000 Sep-Oct:94(5):531-4 [PubMed PMID: 11132383]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceVan Meensel B, Van Wijngaerden E, Verhaegen J, Peetermans WE, Lontie ML, Ripert C. Laboratory diagnosis of schistosomiasis and Katayama syndrome in returning travellers. Acta clinica Belgica. 2014 Aug:69(4):267-72. doi: 10.1179/2295333714Y.0000000039. Epub 2014 Jun 10 [PubMed PMID: 24916752]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDevidas A, Lamothe F, Develoux M, Gakwaya I, Ravisse P, Sellin B. [Morbidity due to bilharziasis caused by S. haematobium. Relationship between the bladder lesions observed by ultrasonography and the cystoscopic and anatomo-pathologic lesions]. Acta tropica. 1988 Sep:45(3):277-87 [PubMed PMID: 2903629]

Burki A, Tanner M, Burnier E, Schweizer W, Meudt R, Degrémont A. Comparison of ultrasonography, intravenous pyelography and cystoscopy in detection of urinary tract lesions due to Schistosoma haematobium. Acta tropica. 1986 Jun:43(2):139-51 [PubMed PMID: 2874711]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAllan F, Dunn AM, Emery AM, Stothard JR, Johnston DA, Kane RA, Khamis AN, Mohammed KA, Rollinson D. Use of sentinel snails for the detection of Schistosoma haematobium transmission on Zanzibar and observations on transmission patterns. Acta tropica. 2013 Nov:128(2):234-40. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2013.01.003. Epub 2013 Jan 11 [PubMed PMID: 23318933]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceten Hove RJ, Verweij JJ, Vereecken K, Polman K, Dieye L, van Lieshout L. Multiplex real-time PCR for the detection and quantification of Schistosoma mansoni and S. haematobium infection in stool samples collected in northern Senegal. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2008 Feb:102(2):179-85. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2007.10.011. Epub 2008 Jan 3 [PubMed PMID: 18177680]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDanso-Appiah A, Olliaro PL, Donegan S, Sinclair D, Utzinger J. Drugs for treating Schistosoma mansoni infection. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2013 Feb 28:2013(2):CD000528. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000528.pub2. Epub 2013 Feb 28 [PubMed PMID: 23450530]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRichter J, Poggensee G, Kjetland EF, Helling-Giese G, Chitsulo L, Kumwenda N, Gundersen SG, Deelder AM, Reimert CM, Haas H, Krantz I, Feldmeier H. Reversibility of lower reproductive tract abnormalities in women with Schistosoma haematobium infection after treatment with praziquantel--an interim report. Acta tropica. 1996 Dec 30:62(4):289-301 [PubMed PMID: 9028413]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBarakat RM. Epidemiology of Schistosomiasis in Egypt: Travel through Time: Review. Journal of advanced research. 2013 Sep:4(5):425-32. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2012.07.003. Epub 2012 Sep 4 [PubMed PMID: 25685449]

King CH, Dangerfield-Cha M. The unacknowledged impact of chronic schistosomiasis. Chronic illness. 2008 Mar:4(1):65-79. doi: 10.1177/1742395307084407. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18322031]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNdeffo Mbah ML, Poolman EM, Atkins KE, Orenstein EW, Meyers LA, Townsend JP, Galvani AP. Potential cost-effectiveness of schistosomiasis treatment for reducing HIV transmission in Africa--the case of Zimbabwean women. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2013:7(8):e2346. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002346. Epub 2013 Aug 1 [PubMed PMID: 23936578]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence