Introduction

Pediatric abusive head trauma (AHT) most often involves brain injury of infants and young children. Another term for this condition is shaken baby syndrome (SBS). Shaking, blunt impact or the combination can result in neurological injury. AHT is the most dangerous and deadly form of child abuse. [1][2][3]

Abusive head trauma typically involves injury to the intracranial contents or skull of an infant or child younger than 5 years old as a result of violent shaking or blunt impact. The outcome ranges from complete recovery to significant brain damage and death.

Brain and head injuries are the most common cause of traumatic death in children less than 2 years. Early diagnosis is essential but may prove challenging. Often the individuals responsible are evasive. Health professionals may not recognize the signs and symptoms due to the frequent lack of external signs of head trauma or abuse.

The solution to avoiding abusive head trauma is caregiver education to avoid accidental pediatric abusive head trauma and shaken baby syndrome and training health providers to recognize the signs and symptoms. Preventive mental health care is the best option to reduce child abuse. For those children that survive, the long-term financial and medical burden is extensive.

Caregivers rarely admit to the deliberate abuse of infants and children. They are usually evasive, fear repercussions, and invent “accidents” such as:

- Falling down the stairs

- Falling out of a crib, highchair, or bed

- Trauma from other children

Definitions and Considerations

Unless head injuries are obvious, clinicians and healthcare providers may overlook the signs and symptoms of abusive head injury. There are patterns of injuries that suggest abusive head trauma or child abuse. Healthcare providers need to be aware of the typical injuries associated with accidents versus those associated with abuse.[4][5]

Abusive Head Trauma (AHT)

- Injury to the intracranial contents or skull of an infant or child younger than 5 years old, usually resulting from violent shaking or blunt impact.

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the American Academy of Pediatrics have recommended using the term abusive head trauma for injuries from these conditions. They have included shaking, blunt impact, suffocation, and strangulation.

- “Abusive head trauma” also includes injuries from dropping and throwing a child. The term describes the type of injury rather than the mechanism.

- “Abusive head injury” may have legal significance as to the specific means of injury. If a provider diagnoses a child with “shaken baby syndrome,” this may preclude evidence of other types of injuries and allow for more challenges in court. The majority of abusive head trauma victims are younger than a year old, often between 3 to 8 months of age. These injuries can occur in children up to 5 years of age.

- The perpetrator is usually a caregiver or parent, with 65% to 90% being male. The National Center for Shaken Baby Syndrome estimates that each year between 1200 to 1400 children are injured or killed by abusive head injuries annually in the United States.

- Abusive head trauma is the primary cause of death and disability in infants and young children from child abuse. Child abuse has been identified as the major cause of brain injuries in one-fourth of children older than 2.

Pediatric Acquired/Traumatic Brain Injury (PA/TBI)

- Traumatic causes include motor vehicle accidents, sports-related injuries, blast injuries, falls, assaults, and gunshot wounds.

Shaken Baby Syndrome (SBS)

- Abusive head trauma with a pattern of injuries may include retinal hemorrhages and regular patterns of brain injury. Rib fractures, as well as fractures of the ends of long bones, are also seen.

- “Shaken baby syndrome” is used to describe brain injury symptoms consistent with vigorously shaking an infant or small child. The injuries often include unilateral or bilateral subdural hemorrhage, bilateral retinal hemorrhages, and diffuse brain injury. While children can be injured by shaking alone, there is often evidence of blunt trauma, so a more inclusive term, “shaken impact syndrome,” may be used.

- The triad of SBS refers to encephalopathy with a subdural hematoma and retinal hemorrhage. The diagnosis of pediatric abusive head trauma can only be made following a detailed medical examination and testing and should not be based on only these three findings.

Other terminologies involving shaken baby syndrome include:

- Nonaccidental head injury (NAHI)

- Inflicted traumatic brain injury (iTBI)

- Nonaccidental head trauma (NAHT)

- Shaken impact syndrome (SIS)

- Whiplash shaken infant syndrome (WSIS)

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Risk factors for abusive head trauma may include behaviors and situations that involve the child, the family, and the caregiver. Infants who inconsolably cry are at risk of a frustrated caregiver responding with violent shaking. Colic is a risk factor. Infant crying is greatest at 6 to 8 weeks of age and then declines. As a consequence, abusive head trauma peaks during this same period.[6][7][8]

Risk factors for abusive head trauma include:

- Behavioral health problems

- Domestic violence history

- Frustration intolerance

- Lack of childcare experience

- Lack of prenatal care

- Low education level

- Low socioeconomic status

- Single-parent families

- Young parents without support

Acute head trauma perpetrators are most frequently the father or stepfather, mother’s boyfriend, female babysitter, and the mother. Shaking is often associated with the perpetrator’s level of frustration and tension.

Child abuse affects all ethnicities, socioeconomic groups, and races, with boys and adolescents more commonly affected. Infants tend to have increased morbidity and mortality with physical abuse. Multiple factors increase a child’s risk of abuse. These include risks at an individual level, such as disability of the child, unmarried mother, maternal smoking, and parent’s depression. Risks at a familial level are domestic violence at home and more than two siblings at home. Risks at a community level are isolation, lack of recreational facilities, and societal factors such as poverty. Other factors include living in an unrelated adult’s home and being a child previously reported to child protective services (CPS). All of these increase the chance of child maltreatment. There are also protective factors that decrease the risk of child maltreatment, including family support and parental concern. Preventive factors include parental education regarding child development and parenting, social support, and parental resilience.[9][10]

Epidemiology

Shaken baby syndrome is difficult to diagnose. As a result, the incidence is uncertain. This results from a lack of a centralized reporting system, signs of maltreatment not being present, unclear presentation, and acute head trauma not being a single isolated event but one that is part of chronic neglect and abuse that ends in severe morbidity and mortality.[7][11]

In the first year of life, the incidence of abusive head trauma is estimated to be approximately 35 cases per 100,000 infants. The morbidity and mortality from abusive head trauma are significant. Approximately 65% have significant neurological disabilities, and between 5 and 35% of infants die of injuries sustained. Most survivors have both cognitive and neurologic impairment.

Abusive head trauma is a subset of a much larger problem. Each year, millions of families of children are investigated by Child Protective Services for abuse and neglect. On average, over 3 million children per year are the subject of maltreatment reports. Of those, 20% are found to have confirmatory evidence of maltreatment.

Unfortunately, despite extensive research, there are no accurate statistics. Experts believe the incidence of pediatric abusive head trauma is about 1000 to 1500 infants per year. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), of the 2000 children who die from abuse annually, abusive head trauma accounts for approximately 10%. The victim of the shaken baby syndrome is typically between 3 and eight months. It is also reported in newborns and children up to 4 years of age. Up to 25% of all children diagnosed with shaken baby syndrome die from their injuries.[12][13]

New York, California, Texas, Michigan, Florida, Illinois, Massachusetts, Indiana, Ohio, and Kentucky have the highest rates of child abuse.

Pathophysiology

Most often, abusive pediatric head trauma begins with anger and frustration over a screaming infant that will not stop crying. Triggers include:

- Feeding problems

- Toilet-training

- Medical problems such as chronic colic

An incident of abusive head trauma forever changes the lives of caregivers and families. Abusive head trauma is one of the most dangerous forms of child abuse. It is the number one cause of death in children younger than 2 years old. The majority of fatal injuries related to child abuse occur as a direct result of abusive head trauma.

The mechanism of abusive head trauma is shaking injuries that occur from repetitive rapid flexion, extension, and rotation of the head and neck. The rapid movement of the brain striking the skull can tear vessels resulting in bleeding around the brain and a hematoma. An enlarging hematoma may cause pressure within the skull, resulting in more brain damage.

Sheering forces across the brain injure nerve axons resulting in diffuse axonal injury. Infant’s heads are large and heavy, and the neck muscles are still too weak to support a large head. Rapid and repetitive flexion, extension, and rotation result in greater movement. When the impact of the head occurs against an object, additional injuries such as lacerations, bruises, and fractures are seen. Even impact against soft objects can result in significant injury.[14][4][15]

Abusive head trauma typically causes:

- Cerebral edema

- Retinal hemorrhage

- Subdural hematoma. It is the primary cause of subdural hematoma in children.

Infants and young child are more susceptible to head injuries than older children for many reasons:

- In proportion to the rest of the body, the head is larger, which means children land headfirst when they fall.

- A child’s brain has a higher water content than adults, so the brain is more likely to suffer acceleration-deceleration injuries.

- A shaken child is more susceptible to primary injuries, including contusion, hemorrhage, and skull fracture. Secondary injuries are biomolecular inflammatory changes causing the disintegration of neurons and interruptions in the brain's microcirculation.

- Primary injury in infants may result in increased intracranial pressure (ICP), ischemia, and hyperemia.

- Cerebral blood flow is impacted as increased ICP leads to tissue destruction.

- The head and neck are unstable, depending more on support more from ligamentous structures than fully developed bony structures.

- The unmyelinated brain in an infant is more likely to experience shearing injuries.

- Autoregulation of cerebral blood flow is impaired, causing further damage.

- The skull is not fully developed and easily deformed. In trauma, it may compress brain tissue when impacted, causing coup rather than the contrecoup injuries more commonly seen in adults.

- Axons are more easily disrupted because of the shearing of long white matter tracts with acceleration-deceleration injuries resulting in cell death.

History and Physical

Abusive head trauma is a difficult diagnosis to make. It is often misdiagnosed because of a misleading history, variable presentations, and a lack of consistent physical signs of injury. After shaking, infants and children may have findings ranging from nonspecific symptoms that do not require urgent care to acute life-threatening complications. Health care providers will initially misdiagnose a third of infants and children with abusive head trauma. Typically it takes as many as three visits to a health care provider for a correct diagnosis. By then, the initial insult may be compounded by recurrent episodes of shaking. Furthermore, delay in diagnosis often results in increased complications and reinjury.

The initial signs and symptoms of abusive head trauma include decreased interaction, lack of a social smile, poor feeding, vomiting, lethargy, hypothermia, increased sleeping, and failure to thrive. Often these signs and symptoms are mistaken for a virus or other minor illness.

Signs and Symptoms of Abusive Head Trauma

- Apnea

- Bulging fontanel

- Bradycardia

- Cardiovascular collapse

- Chills

- Decreased interaction

- Decreased level of consciousness

- Failure to thrive

- Hypothermia

- Irritability

- Increased sleeping

- Lack of a social smile

- Lethargy

- Microcephaly

- Poor feeding

- Vomiting

- Respiratory difficulty and arrest

- Seizures

The most severe cases of trauma will present with life-threatening signs and symptoms. The individual or individuals responsible may not bring the infant or child in for treatment out of fear of legal repercussions and in the hope that the infant or child will recover over time. Unfortunately, delayed care often has devastating effects on the short and long-term prognosis.

The infant or child may present with mild flu-like signs and symptoms or extreme illness, including apnea, severe respiratory distress, bradycardia, bulging fontanel, decreased consciousness, seizures, and cardiovascular collapse.

A lack of external injury should suggest the possibility of abusive head trauma. A careful physical exam, in some cases, can uncover signs of abusive injury. Exam findings include:

- Bruising anywhere in an infant younger than four months old

- Bruising on the ears, neck, or torso, especially in children younger than four years

- Bulging fontanel

- Cerebral atrophy

- Frenulum injuries

- Hydrocephalus

- Lack of external injury

- Ligature marks

- Retinal hemorrhages

- Long bone, metaphyseal, and rib fractures

- Subdural hematoma

Since many infants and children with abusive head trauma are initially asymptomatic or present with mild symptoms, universal neurologic screening for occult intracranial injury should merit consideration with all patients. Physical manifestations of abusive head trauma include cerebral atrophy, subdural and subarachnoid hemorrhages, retinal hemorrhages, hydrocephalus, and unexplained fractures. The primary neurological indicator of abusive head trauma is altered consciousness, developmental delays, seizures, nausea, and vomiting.

Retinal Hemorrhages

Retinal hemorrhages are usually more severe in abusive head trauma than an accidental blunt head injury. Retinal hemorrhage is also significantly more common in abusive head trauma than occurs in infants injured accidentally. Retinal hemorrhage in abusive head trauma involves most of the retina, from the ora serrata to the posterior pole of the eye.

Obtaining an ophthalmology consultation within the first 24 hours is important. Small-dot or superficial hemorrhages often resolve quickly. Less dramatic retinal hemorrhages are also found in children as a result of many other causes, such as accidental head trauma, anemia, birth trauma, coagulopathy, cerebral aneurysm, leukemia, and meningitis. As a result, healthcare providers should not use retinal hemorrhage alone to diagnose abusive head trauma. Further, the absence of retinal hemorrhage confined to the posterior pole also does not rule out abuse.

Subdural Hematoma

A subdural hematoma is a common finding in abusive head trauma. Acceleration-deceleration force causes the brain to move within the fixed venous channels and skull. Hemorrhages occur in the subarachnoid and subdural space if there is tearing of the superficial cortical veins.

Rib Fractures

Rib fractures in an infant are common with child abuse. They occur by squeezing the infant’s chest, which generates anterior-posterior compressive forces resulting in fractured ribs. Accidental rib fractures are very uncommon. Most caregivers will deny a history of trauma. The fractures are detected on routine chest X-rays or a skeletal survey. Rib fractures from CPR are also very rare. Essentially, any infant or child with a rib fracture and a history that does not strongly support legitimate trauma should induce further clinical investigation, which should include a chest X-ray and a skeletal survey.

Skull Fractures

Skull fractures are a result of a direct force applied to the head. They may be due to accidental or inflicted head trauma. Abusive head trauma should be considered when the fracture is complex, diastatic (width greater than 3 mm), multiple, occipital, and non-parietal. Any of these types of skull fractures should suggest the possibility of abusive head trauma.

Other Fractures

Long bone, posterior rib, or metaphyseal “corner” fractures are seen more often in abusive head trauma than in accidental head injuries.

Metaphyseal fractures involve the distal and proximal tibia, proximal humerus, and distal femur. They are known as “bucket-handle” fractures because they appear to have a curvilinear structure coming from the metaphysis when viewed from certain angles. They are seen in infants and children and are highly specific for child abuse. The mechanism is shearing and torsional strains of the metaphysic near the physis. This is caused by shaking, twisting, or pulling on the extremities.

Abusive head trauma does not always present with retinal or subdural hemorrhage or traumatic brain injury. Unexplained cervical spine injuries, seizures, or fractures should also lead the clinician to consider abusive head trauma.

Evaluation

If abusive head trauma is a consideration, a detailed diagnostic evaluation is necessary. Evaluation should include a comprehensive history, physical, laboratory testing, imaging, and consultation with specialists.[1][16][17]

The evaluation should include a review of the timeline of the signs and symptoms leading up to the evaluation. Clinicians should ask open-ended questions that can minimize unintentional bias and allow the opportunity to learn alternative explanations for injuries. A history that does not include trauma or a fall from a low height is the most common in abusive head trauma cases. Caregivers of children injured accidentally will usually report a history of trauma. An inconsistent history or history that changes are suggestive of abusive head trauma and child abuse. The clinician should identify the development and progression of symptoms. Signs and symptoms of abusive head injury occur immediately in over 90% of infants who suffer shaking.[18]

- Note when the child became symptomatic.

- A detailed description of the events

- If more than one caretaker was present, they should be interviewed separately.

- An inconsistent history is a red flag for abuse.

The physical exam should include a head-to-toe assessment. The neurological exam merits particular attention.

Tests

- Complete blood count (CBC) with platelets

- Chemistry panel

- Liver and pancreatic function

- Urinalysis

- CT/MRI/MRA

- Skeletal survey

Imaging

Imaging studies are the most likely test to confirm abusive head trauma. The clinician should initially obtain a skeletal survey and head CT scan.

CT Scan

The head CT is the most helpful test in the diagnosis of intracranial injury from abusive head trauma. While definitive, if positive, a CT may not detect edema, fractures, or shear injury. Often a head CT should be followed by an MRI.

MRI

An MRI can help distinguish a chronic subdural from subarachnoid collections, detect subacute and chronic subdural blood, and define the extent of a parenchymal injury. The use of diffusion MRI may further assist in obtaining an accurate diagnosis.

Skeletal Survey

A skeletal survey should be obtained in any child younger than two years of age with unexplained traumatic injuries.

A skeletal series consists of plain radiographs of the spine, skull, ribs, and long bones. They are commonly successful in identifying abuse. A “babygram,” which is a single image, should be avoided because of the poor detail it provides. Follow-up rib films should be considered 2 or 3 weeks after the initial skeletal survey to evaluate for healing fractures that were not seen in the acute phase.

Bone Scans

Bone scans are an alternative to skeletal surveys and are used if there is a high suspicion of fractures that did not show up on a skeletal survey. Bone scans are more expensive and difficult to perform. Also, bone scans expose the child to more radiation.

Laboratory

Laboratory studies should include complete blood cell count with platelet count, chemistry panel, prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, amylase, lipase, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, and urinalysis. The laboratory evaluation may suggest abusive head trauma by uncovering additional injuries that support child abuse or finding an underlying disease that would be misdiagnosed as child abuse or abusive head trauma.

Treatment / Management

Most of the care of abusive head trauma is supportive. Vital signs should be monitored. Intubation and mechanical ventilation may be required. Intracranial pressure, if present, should be monitored and treated. If there is a subdural hematoma, surgical evacuation should be considered. The goal of therapy is to maintain low intracranial pressure while maintaining acceptable blood pressure, ensuring adequate cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP).[19][11][20]

First-Tier Therapy

The initial management of a child with a traumatic brain injury is maintaining the patient’s airway, breathing, and circulation. Children with no alterations of consciousness and normal blood pressure may be managed with supportive care. Hypotension is treated with fluid boluses. Those with a Glasgow coma score of less than 9, marked respiratory distress, or hemodynamic instability may require advanced airway management to enhance oxygenation and ventilation and prevent aspiration.

Cervical spine immobilization must be maintained during advanced airway procedures. Consider the immediate brain injury resulting from the initial traumatic forces equally important to the two forms of secondary brain injury that may occur. The first form of secondary brain injury includes coagulopathy, hypoxemia, hypotension, intracranial hypertension, hypercarbia, hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia, electrolyte abnormalities, enlarging hematomas, seizures, and hyperthermia. The acute management of severe head injury is to ameliorate those circumstances that lead to secondary brain injury. Secondary brain injury is a consequence of an endogenous cascade of cellular and biochemical events that occur within minutes in the brain and continues for months after the primary brain injury that lead to ongoing traumatic axonal injury (TAI) and neuronal cell damage and, ultimately, neuronal cell death. The following conditions can exacerbate secondary brain injury:

- Coagulopathy

- Elevated intracranial pressure resulting in intracranial hypertension

- Electrolyte abnormalities

- Enlarging hematomas

- Hypoxemia

- Hypotension

- Elevated intracranial pressure leading to intracranial hypertension

- Hypercarbia or hypocarbia

- Hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia

- Hyperthermia

- Seizures

Oxygenation is monitored using pulse oximetry, with supplemental oxygen administered to ensure adequate oxygenation. For initial monitoring of traumatic brain injury ventilation, capnography is recommended to monitor end-tidal carbon dioxide to avoid excessive hyperventilation and hypocapnia, leading to vasoconstriction and decreased cerebral perfusion. Intracranial pressure management is crucial to prevent secondary brain injury. Raising the patient's head to 30 degrees optimizes cerebral perfusion pressure and decreases intracranial pressure by improving venous drainage without affecting cerebral blood flow.

Second-Tier Therapy

Traumatic brain injury can cause intracranial hypertension. These patients require sedation with barbiturates, which lowers intracranial pressure by decreasing cerebral metabolism, decreasing cerebral blood flow.

Third-Tier Therapy

- Decompressive craniectomy for signs of herniation, neurologic deterioration, or those not responding to prior therapy.

- This surgical procedure involves removing part of the skull allowing for swelling to occur while limiting secondary injury.

Differential Diagnosis

If the diagnosis of abusive head trauma is being considered, other causes should be excluded. Accidental head trauma, birth trauma, bleeding diathesis, congenital conditions, neoplastic conditions, metabolic conditions, meningitis, connective tissue diseases, and obstructive hydrocephalus are all part of the differential. These conditions have similar findings as abusive head trauma and must be excluded. Other considerations include osteogenesis imperfecta, glutaric aciduria, vitamin K deficiency, and rebleeding into a prior subdural hematoma.

The differential diagnosis includes:

- Accidental head trauma

- Acute subdural

- Arteriovenous malformation

- Bleeding disorders

- Blood dyscrasias

- Cerebellar hemorrhage

- Connective tissue disorders

- Epidural hematoma

- Infectious subdural effusion

- Intracranial hemorrhage

- Metabolic disorders such as glutaric aciduria type 1, which causes retinal hemorrhages

- Stroke

- Subdural empyema

Injuries That May Be Abusive Head Trauma

- Children may develop serious head injuries from falls. However, the majority do not cause serious head trauma. Any child with severe injuries related to a fall requires further examination, and the diagnosis of abusive head trauma should be considered.

- Falls from a bed, unless it is a bunk bed, are usually minor, although some may have a fracture of the arm, leg, clavicle, or skull. Severe head trauma is rare. The degree of injury depends on the type of flooring and the distance of the fall. Carpeting or padded flooring is associated with a lower incidence of significant injury.

- Falls down the stairs are a significant risk for injury, especially if the child is in a walker or stroller. About 1 to 8% develop intracranial bleeds. If the child was held and dropped while walking down or up the stairs, injuries are less severe. Single injuries to the head or extremities usually predominate. Multiple injuries are uncommon. Stairway injuries are usually less severe than free falls.

- Short vertical falls of 1 to 4 feet rarely cause severe head trauma or multiple injuries. One study of deaths in those children who died after a fall of 1 to 4 feet usually found other evidence consistent with abuse. Another study looked at children who died after a 5 to 6 feet fall and found that most had some evidence of abuse. Falls from 10 feet or higher rarely result in death unless the height is extreme. The greater the height, the greater the incidence of fractures and injuries. A study of 75,000 cases from the United States Consumer Product Safety Commission found that 18 children suffered fall-related injury deaths. Seven fell from a swing and eleven from a horizontal surface, such as a ledge or ladder.

Staging

Researchers have attempted to classify the stage or severity of the injuries as mild (15%), moderate (13%), and severe (70%). The results of the classification reveal some disturbing findings.

- Even mild abusive head injury causes disability greater than a severe burn.

- Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) is the sum of years of productive life lost to disability plus life-years lost to premature death. It has an estimated lifetime burden of 4.7 DALYs for mild abusive head trauma, 5.4 for moderate abusive head trauma, 24.1 for severe abusive head trauma, and 29.8 for deaths from abusive head trauma.

- On average, DALY loss for those who survived at least 30 days was 7.6 years of lost life expectancy and 5.7 years for those that lived with disability.

- The estimated abusive head trauma toll in the United States is over 70,000 DALYs.

Four variables predict abusive head trauma with 98% accuracy.

- Acute respiratory compromise before admission

- Bruising of the ears, neck, and torso

- Bilateral or interhemispheric subdural hemorrhages

- Skull fractures other than of a single, unilateral, nondiastatic, linear, or parietal variety

Prognosis

There are substantial morbidity and mortality associated with abusive head trauma. Morbidity ranges from mild learning disabilities to severe cognitive or physical abnormalities and death. Blindness, attention deficit, developmental delays, intellectual deficits, sensory deficits, hearing impairment, motor dysfunction, failure to thrive, feeding difficulties, seizures, behavior, and educational difficulties are expected manifestations.[21][22][23]

Abusive head trauma may also cause hemiplegia, quadriplegia, hydrocephaly, and microcephaly. The prognosis of patients with abusive head trauma correlates with the extent of injury identified on CT and MRI imaging.

Long-term survivors of severe abusive head trauma have a substantial reduction in quality of life. Even those with mild injuries may have a substantial lifetime impairment.

Studies have evaluated the neurodevelopmental outcomes after abusive head trauma versus accidental head injuries. They found that infants younger than 36 months old with abusive head trauma experience more frequent non-contact injury mechanisms that result in cardiorespiratory compromise, deeper brain injuries, diffuse cerebral hypoxia-ischemia, and worse outcomes than those with an accidental head injury. Children diagnosed with abusive head trauma are more likely to die than children with accidental head trauma.

- More than half of children aged 0 to 4 years injured by abusive head trauma will die before they turn 21.

- Children who are severely injured from abusive head trauma have a 55% reduction in health-related quality of life.

Abusive head trauma commonly causes a number of long-term sequelae. More than 50% of children will have partial or complete blindness. Another 5% need eye surgery, and more than 20% will require a feeding tube after the injuries.

Complications

Complications include:

- Acquired microcephalus

- Cortical blindness

- Developmental delay

- Hearing loss

- Hydrocephalus

- Learning disabilities

- Retinal hemorrhages

- Macular thinning

- Retinal pigment epithelial atrophy

- Seizures

- Spasticity

- Visual loss

- Weakness

Patients with bilateral retinal hemorrhages tend to have an acute, severe neurologic injury. Large subhyaloid hemorrhage, diffuse involvement of the fundus, or vitreous hemorrhage are associated with neurologic injury.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Consider occupational and physical therapy consultations. Speech therapy should also merit consideration if language or speech is affected.

Consultations

- An ophthalmologist should be consulted who is well experienced in identifying eye findings in abused children.

- Refer to appropriate state or county protective (abuse) center as well as evaluation by child protective services.

- Refer to a clinician who specializes in abuse.

- Refer for evaluation by a pediatric neurologist.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Society has a strong ethical and financial obligation to reduce abusive head trauma as the preventable damage to children is significant. The long-term financial costs to society are extensive.

- The annual medical cost related to abusive head trauma in the United States is over $70 million.

- Victims of abusive head trauma require long-term education, occupational, physical, occupational, and speech-language therapies.

- Some victims may require lifetime nursing home care.

- Perpetrators are usually remorseful, and expensive incarceration ruins their lives.

Prevention of abusive head trauma focuses on reducing child abuse, maltreatment, and increasing education. This includes public service announcements, pamphlets, and brochures. Education is also focused on family resource centers and home visit programs, particularly in high-risk homes, e.g., young parents living in poverty. These programs can include mental and social services. Before discharge from the hospital, new parents should be instructed in the danger of shaking a child. Healthcare providers in pediatric offices and the emergency department must be trained and educated to identify parents at high risk of infant abuse. Parents need to be taught coping skills to deal with crying and the danger of shaking a baby with an undeveloped brain.

Abusive head trauma is a preventable problem and a major societal challenge. Two national health initiatives are described below.

The Period of PURPLE Crying program is focused on education concerning normal infant behaviors, such as crying, that can frustrate caregivers. PURPLE stands for Peak (crying peaks at about 2 months, then decreases), Unpredictable, Resistant (to any soothing), Painlike (look on face), Long (bouts of crying), and Evening (most common time of crying).

The National Center on Shaken Baby Syndrome targets new and future parents. The organization attempts to increase skills and confidence as parents.

Healthcare providers can impact the incidence of abusive head trauma by educating caretakers on the dangers of shaking an infant. Prevention should be stressed in all encounters with families. Abusive head trauma syndrome education materials are available through several organizations such as the American Academy of Pediatrics, the National Center on Shaken Baby Syndrome, and Prevent Child Abuse America.

Prevention is the key; all providers of health care must work together to educate the public. Incessant crying is the major trigger of abusive head trauma. Recognition and education of high-risk caregivers will lower the incidence of pediatric abusive head trauma.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Child abusive head trauma, and child abuse are public health problems that lead to lifelong health consequences, both physically and psychologically. Physically, those who undergo abusive head trauma may have neurologic deficits, developmental delays, cerebral palsy, and other forms of disability. Psychologically, child abuse victims tend to have higher rates of depression, conduct disorder, and substance abuse. Academically, these children may have poor performance at school with decreased cognitive function. Every healthcare professional has a responsibility both legally and ethically in identifying cases of child abuse.[18][19][20]

- Clinicians must have a high index of suspicion for child maltreatment, as early identification may be lifesaving.

- Healthcare providers may have ethical concerns about the legal implications of a preliminary diagnosis of abusive head trauma, but providers are legally and morally required to report suspected abuse to child protective services in all states. As a result, if child abuse or abusive head trauma is suspected, it is important to take the time to do a thorough assessment to rule out other potential causative factors in the differential diagnoses.

- It is crucial and necessary to provide thorough documentation as most cases of abusive head trauma result in legal action against the responsible caregiver.

- The early identification of abusive head trauma is particularly important. Studies have suggested that 80% of deaths associated with abusive head trauma might have survived with earlier intervention.

- While children younger than 2 years of age are the most common victims of abusive head trauma and typically exhibit the classic signs, one study of children 2 to 7 years showed that they exhibited similar signs and symptoms, which included bilateral retinal hemorrhages, diffuse axonal injury, and acute subdural hematoma.

Due to the frequency, negative impact on infants and children, and expense to society, it is imperative that clinicians become proficient in recognizing the signs and symptoms of abusive head injury. All health providers that evaluate children should be:

- Vigilant and cognizant of the signs, symptoms, and patterns of head trauma associated with abusive head trauma.

- Learn how to conduct a thorough, objective assessment of infants and children exhibiting signs and symptoms of possible abusive head trauma.

- Trained to consult ophthalmologists, radiologists, and neurosurgeons to assist in interpreting findings and confirm the diagnosis.

- Able to ensure a complete medical assessment and make an accurate diagnosis.

Clinicians that take care of infants and children should always remember:

- Use the term abusive head trauma rather than a shaken baby syndrome or another term that suggests a single mechanism of injury.

- Educate parents and caregivers regarding the dangers of shaking or striking an infant or child's head.

- Participate in community-based prevention efforts that teach parents the importance of only leaving children in the care of adults who can be trusted not to harm the child accidentally or deliberately.

- All clinicians must recognize, report, and respond appropriately to suspected child abuse and neglect.

While the diagnosis of abusive head trauma may sometimes be readily apparent, inexperienced and unsuspecting clinicians may fail to recognize injuries caused by child abuse. Further, when the diagnosis is not clear-cut, the clinician must exercise restraint until the evaluation is complete. The care of children with abusive head trauma is best undertaken by an interprofessional team including primary care providers, emergency department physicians and nurses, radiologists, intensivists, and neurosurgeons. [Level 5]

Media

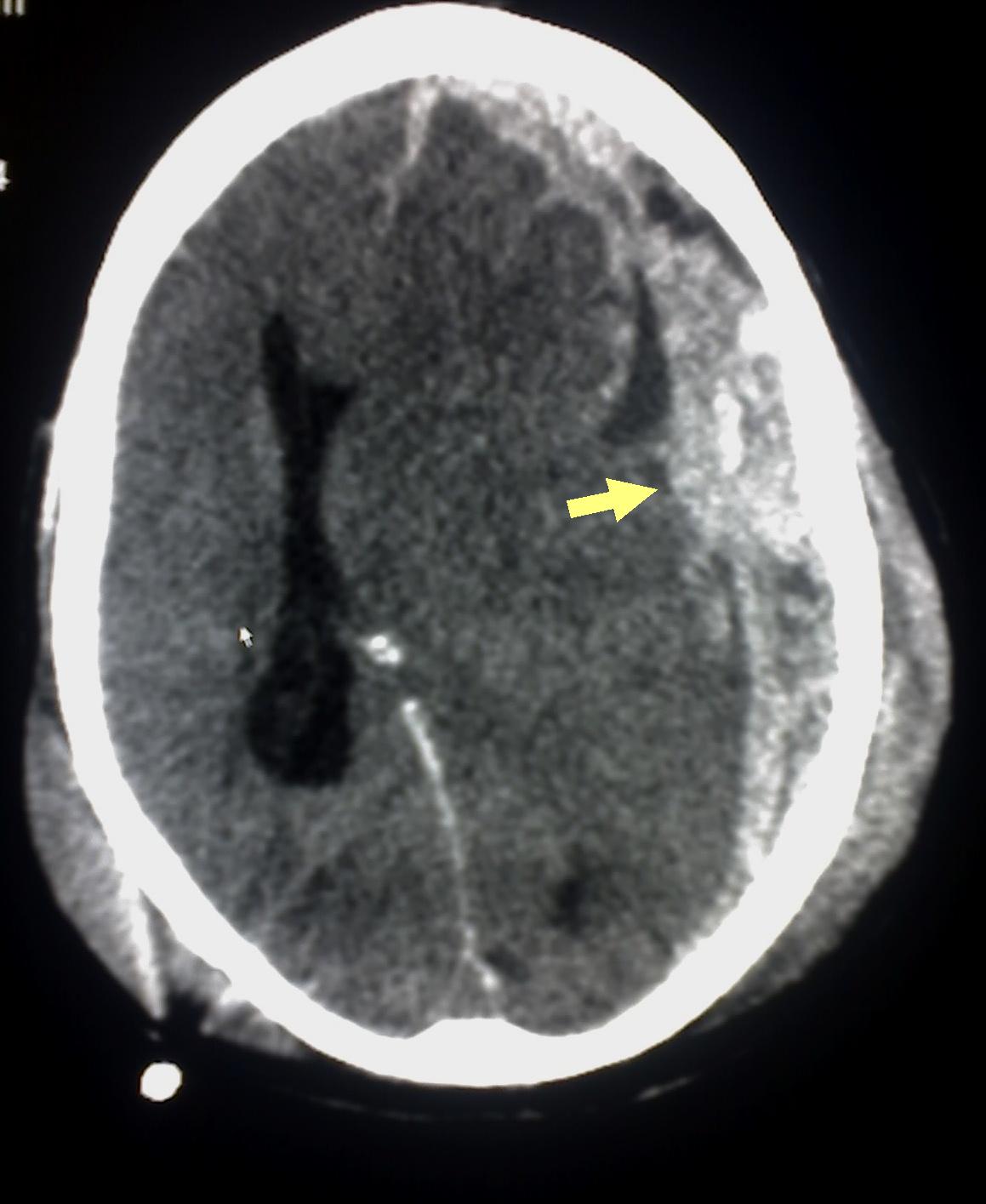

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Subdural Hematoma Detected on Head CT. Abusive head trauma or shaken baby syndrome may cause subdural hematoma (arrow), indicating bleeding between the dura mater of the meninges and the brain, as detected on the head CT of a patient.

Glitzy queen00, (Public Domain), via Wikimedia Commons.

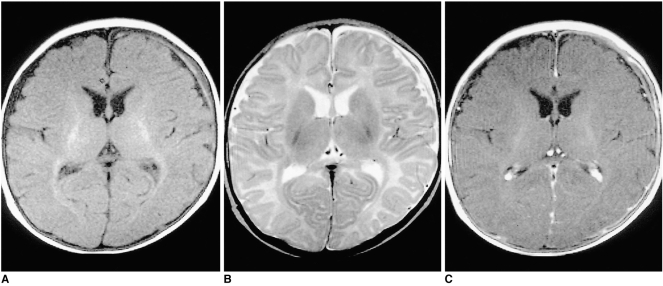

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Shaken Baby Syndrome MRI Chronic subdural hematoma (SDH) in a three-month-old female patient A T1-weighted image shows mainly low-signal SDH, with a high signal focus in the left frontal area. B On a T2-weighted image the signal intensity of the chronic SDH is mainly high, with a focal area of low intensity. C Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted image shows overlying linear dural enhancement. Contributed by The National Center for Biotechnology Information (MRI by The Korean Radiological Society; http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0)

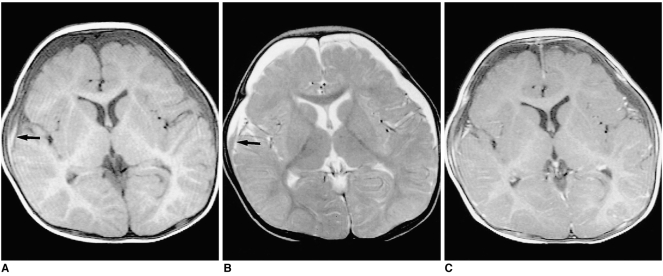

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Shaken Baby Syndrome MRI Chronic Subdural Hematoma in an eight-month-old male patient A; T1-weighted image shows low-signal SDH in both frontal areas. A high signal area, suggesting subacute hemorrhage, may also be observed in the right frontal area (arrow) B; On a T2-weighed image, the signal intensity of the SDH is mainly high, though there is a focal area of low intensity (arrow) C; Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted image shows diffuse linear dural enhancement Contributed by The National Center for Biotechnology Information (MRI by The Korean Radiological Society; http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0)

References

Elinder G, Eriksson A, Hallberg B, Lynøe N, Sundgren PM, Rosén M, Engström I, Erlandsson BE. Traumatic shaking: The role of the triad in medical investigations of suspected traumatic shaking. Acta paediatrica (Oslo, Norway : 1992). 2018 Sep:107 Suppl 472(Suppl Suppl 472):3-23. doi: 10.1111/apa.14473. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30146789]

Vinchon M. Shaken baby syndrome: what certainty do we have? Child's nervous system : ChNS : official journal of the International Society for Pediatric Neurosurgery. 2017 Oct:33(10):1727-1733. doi: 10.1007/s00381-017-3517-8. Epub 2017 Sep 6 [PubMed PMID: 29149395]

Rosén M, Lynøe N, Elinder G, Hallberg B, Sundgren P, Eriksson A. Shaken baby syndrome and the risk of losing scientific scrutiny. Acta paediatrica (Oslo, Norway : 1992). 2017 Dec:106(12):1905-1908. doi: 10.1111/apa.14056. Epub 2017 Oct 10 [PubMed PMID: 28871599]

Chhablani PP, Ambiya V, Nair AG, Bondalapati S, Chhablani J. Retinal Findings on OCT in Systemic Conditions. Seminars in ophthalmology. 2018:33(4):525-546. doi: 10.1080/08820538.2017.1332233. Epub 2017 Jun 22 [PubMed PMID: 28640657]

Saunders D, Raissaki M, Servaes S, Adamsbaum C, Choudhary AK, Moreno JA, van Rijn RR, Offiah AC, Written on behalf of the European Society of Paediatric Radiology Child Abuse Task Force and the Society for Pediatric Radiology Child Abuse Committee. Throwing the baby out with the bath water - response to the Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services (SBU) report on traumatic shaking. Pediatric radiology. 2017 Oct:47(11):1386-1389. doi: 10.1007/s00247-017-3932-8. Epub 2017 Aug 7 [PubMed PMID: 28785782]

Berkowitz CD. Physical Abuse of Children. The New England journal of medicine. 2017 Apr 27:376(17):1659-1666. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1701446. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28445667]

Ludvigsson JF. Extensive shaken baby syndrome review provides a clear signal that more research is needed. Acta paediatrica (Oslo, Norway : 1992). 2017 Jul:106(7):1028-1030. doi: 10.1111/apa.13765. Epub 2017 Mar 29 [PubMed PMID: 28370396]

Reith W, Yilmaz U, Kraus C. [Shaken baby syndrome]. Der Radiologe. 2016 May:56(5):424-31. doi: 10.1007/s00117-016-0106-x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27118366]

Lynøe N, Elinder G, Hallberg B, Rosén M, Sundgren P, Eriksson A. Insufficient evidence for 'shaken baby syndrome' - a systematic review. Acta paediatrica (Oslo, Norway : 1992). 2017 Jul:106(7):1021-1027. doi: 10.1111/apa.13760. Epub 2017 Mar 1 [PubMed PMID: 28130787]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKaribe H, Kameyama M, Hayashi T, Narisawa A, Tominaga T. Acute Subdural Hematoma in Infants with Abusive Head Trauma: A Literature Review. Neurologia medico-chirurgica. 2016 May 15:56(5):264-73. doi: 10.2176/nmc.ra.2015-0308. Epub 2016 Mar 10 [PubMed PMID: 26960448]

Kato N. Prevalence of Infant Shaking Among the Population as a Baseline for Preventive Interventions. Journal of epidemiology. 2016:26(1):2-3. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20150321. Epub 2015 Dec 19 [PubMed PMID: 26686883]

Peterson C, Xu L, Florence C, Parks SE. Annual Cost of U.S. Hospital Visits for Pediatric Abusive Head Trauma. Child maltreatment. 2015 Aug:20(3):162-9. doi: 10.1177/1077559515583549. Epub 2015 Apr 24 [PubMed PMID: 25911437]

Frasier LD, Kelly P, Al-Eissa M, Otterman GJ. International issues in abusive head trauma. Pediatric radiology. 2014 Dec:44 Suppl 4():S647-53. doi: 10.1007/s00247-014-3075-0. Epub 2014 Dec 14 [PubMed PMID: 25501737]

Shekdar K. Imaging of Abusive Trauma. Indian journal of pediatrics. 2016 Jun:83(6):578-88. doi: 10.1007/s12098-016-2043-0. Epub 2016 Feb 17 [PubMed PMID: 26882906]

Nadarasa J, Deck C, Meyer F, Willinger R, Raul JS. Update on injury mechanisms in abusive head trauma--shaken baby syndrome. Pediatric radiology. 2014 Dec:44 Suppl 4():S565-70. doi: 10.1007/s00247-014-3168-9. Epub 2014 Dec 14 [PubMed PMID: 25501728]

Shles A, Stackievicz R, Schwartz R. [SEIZURE IN A BABY - SHAKING THE DIAGNOSIS]. Harefuah. 2017 Dec:156(12):796-798 [PubMed PMID: 29292621]

Fraser JA, Flemington T, Doan TND, Hoang MTV, Doan TLB, Ha MT. Prevention and recognition of abusive head trauma: training for healthcare professionals in Vietnam. Acta paediatrica (Oslo, Norway : 1992). 2017 Oct:106(10):1608-1616. doi: 10.1111/apa.13977. Epub 2017 Aug 11 [PubMed PMID: 28685899]

Trossman S. PRACTICE Preventing tragedies New Mexico nurses lead initiative on shaken baby syndrome. The American nurse. 2016 Sep:48(4):13 [PubMed PMID: 29787658]

Rideout L. Nurses' Perceptions of Barriers and Facilitators Affecting the Shaken Baby Syndrome Education Initiative: An Exploratory Study of a Massachusetts Public Policy. Journal of trauma nursing : the official journal of the Society of Trauma Nurses. 2016 May-Jun:23(3):125-37. doi: 10.1097/JTN.0000000000000206. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27163220]

Nocera M, Shanahan M, Murphy RA, Sullivan KM, Barr M, Price J, Zolotor A. A statewide nurse training program for a hospital based infant abusive head trauma prevention program. Nurse education in practice. 2016 Jan:16(1):e1-6. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2015.07.013. Epub 2015 Aug 14 [PubMed PMID: 26341727]

Barr RG, Barr M, Rajabali F, Humphreys C, Pike I, Brant R, Hlady J, Colbourne M, Fujiwara T, Singhal A. Eight-year outcome of implementation of abusive head trauma prevention. Child abuse & neglect. 2018 Oct:84():106-114. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.07.004. Epub 2018 Aug 1 [PubMed PMID: 30077049]

Lind K, Toure H, Brugel D, Meyer P, Laurent-Vannier A, Chevignard M. Extended follow-up of neurological, cognitive, behavioral and academic outcomes after severe abusive head trauma. Child abuse & neglect. 2016 Jan:51():358-67. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.08.001. Epub 2015 Aug 20 [PubMed PMID: 26299396]

Tilak GS, Pollock AN. Missed opportunities in fatal child abuse. Pediatric emergency care. 2013 May:29(5):685-7. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e31828f3e39. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23640154]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence