Introduction

The cranium (from the Greek word krania, meaning skull) is the most cephalad aspect of the axial skeleton. The cranium, or skull, is composed of 22 bones anis d divided into two regions: the neurocranium (which protects the brain) and the viscerocranium (which forms the face).

The skull also supports tendinous muscle attachments and allows neurovascular passage between intracranial and extracranial anatomy. The skull is embryologically derived from mesoderm and neural crest and will fuse, harden, and mold from gestation through adulthood. It gives the human face its form, and even minor variations in anatomy among individuals can lead to vast differences in appearance.

Various foramina, condyles, and other bony landmarks provide passageways and attachments for the important structures associated with the skull. Due to its complex development and associated important structures, understanding skull anatomy holds great clinical and surgical significance.[1][2][3]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The skull consists of 22 bones in most adult specimens, which come together via cranial sutures. The function of the skull is both structurally supportive and protective. The skull will harden and fuse through development to protect its inner contents: the cerebrum, cerebellum, brainstem, and orbits. In addition, it supports the muscles of the face and scalp by providing muscular and tendinous attachments, protects neurovascular structures, and houses various sinuses to accommodate increases in pressure.

Calvaria and Skull Base

The calvaria, the uppermost part of the skull, protects the cerebral cortex, cerebellum, and orbital contents. It is composed of the frontal bone, parietal bones, temporal bones, and occipital bone. The coronal suture is the transverse mid-anterior junction of the frontal bone and the two parietal bones. The parietal bones articulate with the temporal bones inferiorly via the squamosal sutures and the occipital bone posteriorly via the lambdoid suture. The sagittal suture lies along an anterior-posterior axis and is the articulation of the two parietal bones. The pterion is the articulation of the frontal, parietal, temporal, and sphenoid bones just superior to the pinna. The asterion is the articulation of the parietal, temporal, and occipital bones. Finally, the skull base allows the passage of various neurovascular structures. It is composed of the sphenoid and ethmoid bones (which have their associated air sinuses) and parts of the frontal, temporal, and occipital bones.

Anteriorly, the frontal bone forms the superior aspect of the orbits. The glabella is a key midline landmark of the frontal bone. It lies superior to the nasion and between the superciliary ridges. The frontal sinuses lie deep to the brow ridges. The bregma is the junction of the coronal and sagittal sutures, and lambda is the junction of the lambdoid and sagittal sutures. The temporal bones subdivide into petrous, squamous, zygomatic, and mastoid parts. The petrous portion houses the inner ear. The mastoid is a bony prominence that lies posterior to the auricle and has an associated sinus. The occipital bone is the most posterior aspect of the skull.

Intracranial Fossae

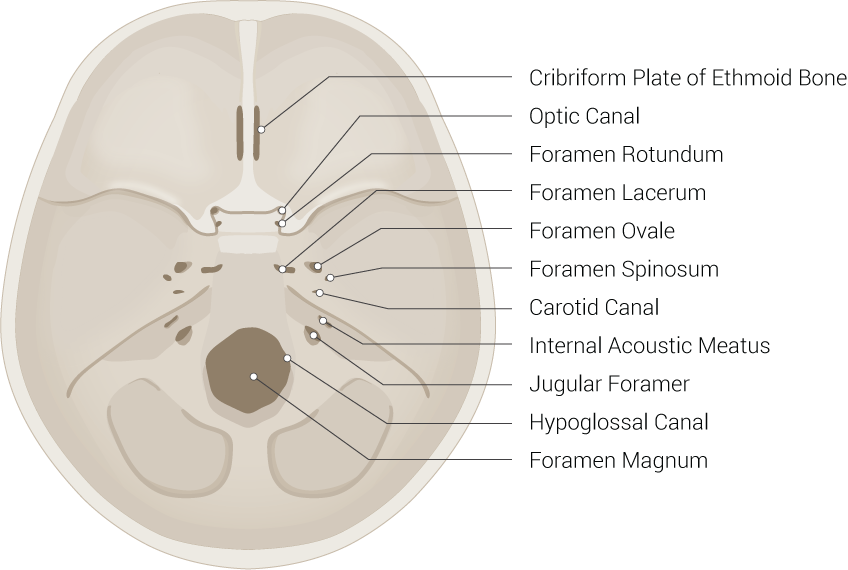

There are three cranial fossae with various structural landmarks. The anterior cranial fossa forms from the frontal bone, the sphenoid bone, and the ethmoid bone. The middle cranial fossa forms from the sphenoid bone and two temporal bones. Finally, the posterior cranial fossa forms from the occipital bone and two temporal bones. The critical anatomic landmarks of each fossa are listed below.

- Anterior Cranial Fossa (contains frontal lobe of the brain)

- Cribriform plate

- Middle Cranial Fossa (contains temporal lobe of the brain)

- Optic canal

- Superior orbital fissure

- Foramen spinosum

- Foramen rotundum

- Foramen ovale

- Posterior Cranial Fossa (contains the cerebellum)

- Internal auditory meatus

- Jugular foramen

- Foramen magnum

- Hypoglossal canal

Facial Bones

There are 14 facial bones with specific anatomical landmarks and embryologic development mechanisms. These include the two nasal conchae, two nasal bones, two maxilla bones, two palatine bones, two lacrimal bones, two zygomatic bones, the mandible, and the vomer. The maxillae have associated air sinuses. The temporomandibular joint (TMJ) is a significant landmark for effective mastication, and its dysfunction is common in adults.[4][5][6][2]

Embryology

Embryologically, the skull derives from ectodermal neural crest and mesoderm. The frontal, ethmoid, and sphenoid bones derive from the neural crest, while the parietal and occipital bones originate from the mesoderm. The temporal bones derive from both the mesoderm and neural crest. The skull develops alongside the rapid growth of the nervous system in the embryonic phase of development (weeks 1 to 8). Ossification and structural molding begin in the fetal phase (week seven onward).

Early Development

Mesoderm begins to form in the third week of gestation after early mesenchymal cells have migrated through the primitive streak. These cells then proliferate in a longitudinal fashion adjacent to the notochord (paraxial mesoderm) and eventually divide into various early connective tissue populations, including the sclerotome and myotome. The sclerotome develops into the mesodermal portions of the skull (parietal bones, occipital bone, and petrous portion of the temporal bone).

Neural crest cells form the rest of the neurocranium: the frontal bone, ethmoid bone, sphenoid bone, and squamous portion of the temporal bone, as well as the entirety of the viscerocranium. Five significant pharyngeal arches form in humans, starting rostral to caudal around days 19 to 21 of gestation. These arches form muscles, cartilaginous and osseous structures, nerves, blood vessels, and various organs of the head and neck. Each arch has components of ectoderm, mesoderm, endoderm, and neural crest. Some of the neural crest components form parts of the viscerocranium previously discussed, including the mandible, maxilla, incus, and malleus (arch 1) and stapes and styloid process of the temporal bone (arch 2).

Several genes play an important role in forming the cranium, including the Dickkopf family, matrix metallopeptidase 9, Indian hedgehog, Sonic hedgehog (Shh), Fibroblast Growth Factor 3, and the family of collagen genes (i.e., COL1A1).

Fetal Development and Ossification

There are two mechanisms by which bones develop and ossify: intramembranous ossification and endochondral ossification. Intramembranous ossification is the direct formation of early bone from undifferentiated mesenchyme without a template, and endochondral ossification utilizes cartilage as a precursor formed by chondrocytes for bone maturation.

The bones of the cranial vault (including the parietal, frontal, occipital, and squamous temporal bones) and viscerocranium (including the maxilla, mandible, and other flat bones of the face) undergo intramembranous ossification. The skull base (including the sphenoid and ethmoid bones) forms via endochondral ossification. Mesenchymal maturation does not occur until after the formation of the neurovasculature, allowing for the development of the foramina. This process is especially important in the skull base, where nerves and blood vessels exit the cranium.[7][8][9]

Branchial Arch Derivatives

- First Branchial Arch - the mandibular nerve of trigeminal nerve (CN V3)

- Second Branchial arch - the facial nerve (CN VII)

- Third Branchial Arch - the glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX)

- Fourth Branchial Arch - the vagus nerve (CN X)

- Sixth Branchial Arch - the superior and recurrent laryngeal nerve branches of the vagus nerve (CN X)

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Most of the blood supply to the skull and its associated structures comes from the common carotid arteries (anterior circulation) and vertebral arteries (posterior circulation).

The common carotid artery bifurcates into the internal and external carotid arteries. The external carotid artery is the main blood supply to the skull bones and meninges. It travels up the side of the neck; eight main branches feed the superficial structures of the skull and face. The maxillary artery is the most prominent and clinically relevant of these branches. The middle meningeal artery is a branch of the maxillary artery, and injury secondary to blunt force trauma to the lateral skull at the pterion can lead to epidural hematoma. The internal carotid artery has no branches in the neck and enters the base of the skull, supplying intracranial structures. The internal carotid and vertebral arteries combine to form a large anastomosis called the circle of Willis. The anterior communicating artery, two anterior cerebral arteries, two middle cerebral arteries, two posterior communicating arteries, two posterior cerebral arteries, and basilar artery (superior continuation of the vertebral arteries) all contribute to this anastomosis.

The dural venous sinuses (i.e., superior sagittal, straight, and transverse sinuses) and superficial and deep veins of the head (i.e., cerebral veins, great vein of Galen, cerebellar, and facial veins) drain into the internal and external jugular veins bilaterally and ultimately to the superior vena cava and right atrium of the heart.

The brain and central nervous system have been traditionally thought not to contain lymphatic vessels. However, some believe that the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) does have some connection with the lymphatic system and drains through the cervical lymph nodes. The recent discovery of a “glymphatic system,” composed of a network of CSF, cerebral interstitial fluid, and meningeal vasculature, has shed more light on this debate and is an area of ongoing research.[10][11]

Nerves

The skull has multiple foramina that allow passage of neurovascular structures into and out of the skull. The cranial nerves and some vessels mostly exit via foramina in the cranial base. Below is a brief list of the most important foramina and associated structures.

- Cribriform plate: olfactory nerve (CN I)

- Optic canal: optic nerve (CN II) and the ophthalmic artery

- Superior orbital fissure: oculomotor nerve (CN III), trochlear nerve (CN IV), abducens nerve (CN VI), ophthalmic division of trigeminal nerve (CN V1)

- Foramen rotundum: maxillary division of trigeminal nerve (CN V2)

- Foramen ovale: mandibular division of trigeminal nerve (CN V3)

- Stylomastoid foramen: facial nerve (CN VII)

- Internal auditory meatus: facial nerve (CN VII) and vestibulocochlear nerve (CN VIII)

- Jugular foramen: glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX), vagus nerve (CN X), spinal accessory nerve (CN XI), and the jugular vein

- Hypoglossal canal: hypoglossal nerve (CN XII)

- Foramen magnum: brainstem, the spinal root of the accessory nerve (CN XI), and the vertebral arteries

Other key foramina that may or may not be associated with nerves include the foramen spinosum (middle meningeal artery), carotid canal (internal carotid artery and sympathetic plexus), and supraorbital and infraorbital foramina (supraorbital and infraorbital nerves). The superficial sensory nerves of the skull, scalp, and face receive input from branches of the trigeminal nerve anteriorly and the greater and lesser occipital nerves posteriorly.[12][13][14]

Muscles

The muscles of the face and scalp are predominantly striated muscles under voluntary innervation. They serve crucial roles in facial expression, vision, language, and mastication. The majority of these muscles are innervated by the facial nerve, oculomotor nerve, or trigeminal nerve, while the hypoglossal nerve innervates the tongue. Small smooth muscles of the eye are under sympathetic or parasympathetic control for lens accommodation, aqueous humor production, and other functions.[15]

Oculomotor Nerve (CN III)

The superior division of CN III innervates the superior rectus muscle and the striated muscle component of the levator palpebrae superiors muscle. The inferior division of CN III innervates the medial and inferior rectus muscles and the inferior oblique muscle.

Trigeminal Nerve (CNV)

The mandibular nerve (V3) of the trigeminal nerve innervates eight muscles, four of which are used in mastication. The masseter and temporalis muscles elevate the mandible during mastication, while the lateral pterygoid protrudes the mandible. The medial pterygoid allows for lateral movement of the mandible, rocking it from side to side.

Also innervated by V3 of CN V are the anterior belly of the digastric muscle, the mylohyoid muscles, the tensor tympani used to dampen sounds, and the tensor veli palatini, which tenses the soft palate.

Facial Nerve (CN VII)

The motor root of CN VII innervates the stylohyoid muscle, the posterior belly of the digastric muscles, and the following muscles of facial expression:

- Buccinator

- Corrugator supercilii

- Depressor anguli oris

- Frontalis (part of occipitofrontalis)

- Levator labii superioris alaque nasi

- Mentalis

- Orbicularis oculi

- Orbicularis oris

- Platysma

- Procerus

- Risorius

- Zygomaticus major

- Zygomaticus minor

Glossopharyngeal Nerve (CN IX)

The stylopharyngeus muscle, which raises and dilates the pharynx, is innervated by CN IX.

Vagus Nerve (CN X)

The pharyngeal plexus is derived from CN X and innervates the musculus uvulae, the levator veli palatini, and many other muscles of the soft palate. Also innervated by the pharyngeal plexus are the salpingopharyngeus muscle and the superior, middle, and inferior pharyngeal constrictors.

The cricothyroid muscle is innervated by the external laryngeal branch of the superior laryngeal nerve, which is a branch of CN X. The motor component of the recurrent laryngeal nerve is also a branch of CN X and supplies the following muscles: oblique and transverse arytenoids, lateral and posterior cricoarytenoids, the thyroarytenoids, and the vocalis muscles.

Spinal Accessory Nerve (CN XI)

The sternocleidomastoid and trapezius receive motor innervation from CN XI.

Hypoglossal Nerve (CN XII)

The hypoglossal nerve (CN XII) mainly innervates the intrinsic muscles of the tongue. Its motor component also innervates the hyoglossus, genioglossus, and styloglossus muscles. A branch of C1 travels with CN XII to innervate the geniohyoid muscle. Of note, the palatoglossus muscle, despite its action to elevate the tongue, is innervated by CN X.

Physiologic Variants

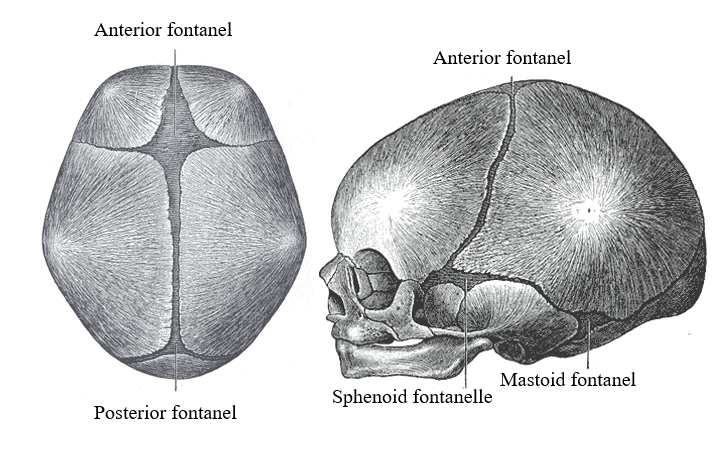

Fontanelles and Cranial Sutures

Fontanelles are soft areas where the skull has not ossified to allow for brain growth and development. There are six fontanelles, with the anterior and posterior being the most prominent and clinically significant. The anterior fontanelle closes around age 1 to 2 years and hardens to become the bregma and adjacent coronal suture. The posterior fontanelle closes around 6 to 8 weeks of age and becomes the lambda and adjacent lambdoid suture.

The sutures of the skull allow for movement of the cranial bones during infancy, which persists into adulthood. Eventually, these sutures fuse and are no longer moveable. There is a great deal of variation in the timing of the closure of individual sutures. The sagittal suture closes first around age 22, then the coronal suture, followed by the lambdoid around age 26, and the squamous sutures around age 60. The metopic suture splits the frontal bones and typically closes at three months of age but can take up to nine months.

Skull Abnormalities and Embryologic Pathophysiology

Skull abnormalities and neural tube malformations such as anencephaly are unfortunately fairly common due to several factors. Many cranial structures develop early in utero and are vulnerable to toxic insults in unplanned pregnancies. Folate and other nutritional deficiencies and substance abuse can hinder the development and proper growth of the axial skeleton and central nervous system and, in some cases, lead to early miscarriage. Disorders of chromosome number and single genetic defects (i.e., Shh mutations) are also associated with cranial malformations.

Neural crest abnormalities can lead to cleft palate, inner ear problems, or other skull abnormalities. The premature fusion of cranial sutures is termed craniosynostosis and leads to differences in skull shape (i.e., brachycephaly and plagiocephaly). Treacher-Collins syndrome is a craniofacial disorder characterized by an interruption of normal embryonic growth, specifically the development of the first and second embryonic arches. The syndrome commonly presents with mandibular hypoplasia, facial abnormalities, and craniosynostosis.[7][8]

Surgical Considerations

Neurosurgeons, ophthalmologists, interventional radiologists, and otorhinolaryngologists must have a strong understanding of normal and variant skull anatomy. Due to the inability of the skull to accommodate rapid or significant increases in intracranial pressure and the serious deficits that can arise from damage to the skull’s associated anatomy, many pathophysiologic conditions, including strokes, tumors, fractures, and infections are considered emergent conditions and often require surgical management. Below is a brief description of two of the most common skull-related surgical operations.

Craniotomy

A craniotomy is the neurosurgical removal of a portion of the skull to gain access to the meninges, brain, and other intracranial structures. Its indications are for treating intracranial hemorrhage, aneurysms, tumors, infection, or congenital malformations. Preoperative imaging is often utilized to localize the pathological entity. Still, clinical knowledge of the superficial anatomy of the skull and neurovasculature is paramount to ensure adequate exposure and limit intraoperative and postoperative complications.

Transsphenoidal Hypophysectomy

Pituitary adenomas that are large (>10 mm), functional, or pharmacologic-refractory are often surgically managed to prevent long-term morbidity. This procedure is often performed via transsphenoidal resection of the tumor under the management of a neurosurgeon, often in conjunction with or primarily by an otorhinolaryngologist. The mass can be extracted via the sphenoid sinus with the intraoperative assistance of a surgical microscope or endoscope. If preoperative imaging or ontraoperative visualization indicates that the mass has grown beyond the sella turcica, an open approach may be necessary.[16][17][18]

Clinical Significance

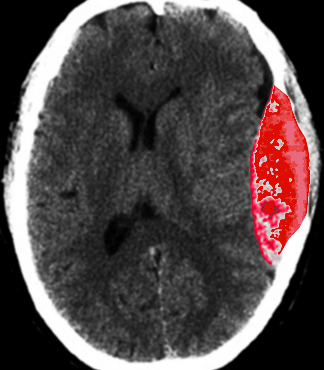

Epidural Hematoma

Epidural hematoma results from a lacerated middle meningeal artery, often caused by blunt force trauma to the lateral skull superior to the ear at the pterion. Arterial hemorrhage in the epidural space (a potential space between the dura mater and the overlying skull) accumulates quickly and does not cross suture lines. Thus, compression and eventual herniation of the brain can lead to focal neurologic deficits, confusion, and death. Patients will often present with abrupt syncope that quickly resolves. After a brief lucid interval where the patient may feel normal, significant focal neurologic deficits and signs of increased intracranial pressure may develop. Computed tomography (CT) will display a classic hyperdense “lens-shaped” lesion, and treatment is emergent craniotomy and hematoma evacuation.

Basilar Skull Fractures

Fractures of the skull base should be considered whenever a significant trauma mechanism is involved (most often, a motor vehicle collision). The patient’s presenting signs and symptoms will depend on the location and extent of the fracture. However, patients often present with periorbital ecchymosis (raccoon eyes) and postauricular ecchymosis (battle sign), CSF rhinorrhea or otorrhea if the cribriform plate or petrous temporal bone is fractured, and focal or global neurologic deficits. Thin-slice CT has become an integral part of diagnosing subtle skull base fractures.[19][20][21][20]

Other Issues

When interpreting imaging of the skull, a strong understanding of the sutures and their normal variants is needed because of the easy misinterpretation of a suture for a fracture; this is especially true with the increasingly prevalent use of high-resolution CT scans as they can now pick up subtle fractures and the cranial sutures. The anatomy of a child’s skull is continually changing, and these variations are essential to note. Clinical correlation is often necessary in these cases.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

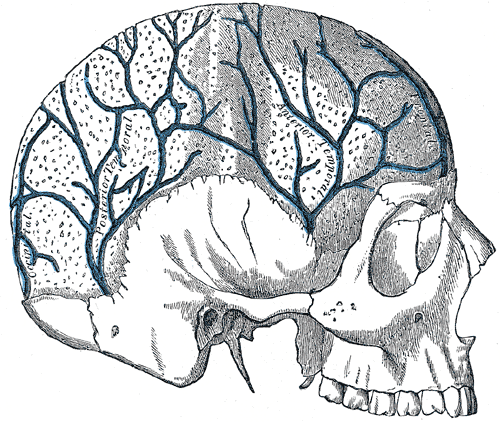

Veins in the Skull. Veins in the skull: occipital, posterior temporal, and anterior temporal.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Superior and lateral view of the newborn skull and its fontanels

Henry Vandyke Carter, (plate 197, 198), Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Barber SR, Wong K, Kanumuri V, Kiringoda R, Kempfle J, Remenschneider AK, Kozin ED, Lee DJ. Augmented Reality, Surgical Navigation, and 3D Printing for Transcanal Endoscopic Approach to the Petrous Apex. OTO open. 2018 Oct-Dec:2(4):2473974X18804492. doi: 10.1177/2473974X18804492. Epub 2018 Oct 29 [PubMed PMID: 30719506]

Singh O, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Head and Neck: Frontal Bone. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30571045]

Abdullah B, Lim EH, Husain S, Snidvongs K, Wang Y. Anatomical variations of anterior ethmoidal artery and their significance in endoscopic sinus surgery: a systematic review. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2019 May:41(5):491-499. doi: 10.1007/s00276-018-2165-3. Epub 2018 Dec 12 [PubMed PMID: 30542930]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKim SM, Paek SH, Lee JH. Infratemporal fossa approach: the modified zygomatico-transmandibular approach. Maxillofacial plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2019 Dec:41(1):3. doi: 10.1186/s40902-018-0185-x. Epub 2019 Jan 11 [PubMed PMID: 30687683]

Visocchi M. Why the Craniovertebral Junction? Acta neurochirurgica. Supplement. 2019:125():3-8. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-62515-7_1. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30610295]

Patel BC, Malhotra R. Mid Forehead Brow Lift. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30571073]

Graham A. The development and evolution of the pharyngeal arches. Journal of anatomy. 2001 Jul-Aug:199(Pt 1-2):133-41 [PubMed PMID: 11523815]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJin SW, Sim KB, Kim SD. Development and Growth of the Normal Cranial Vault : An Embryologic Review. Journal of Korean Neurosurgical Society. 2016 May:59(3):192-6. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2016.59.3.192. Epub 2016 May 10 [PubMed PMID: 27226848]

Berendsen AD, Olsen BR. Bone development. Bone. 2015 Nov:80():14-18. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2015.04.035. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26453494]

Thomas JL, Jacob L, Boisserand L. [Lymphatic system in central nervous system]. Medecine sciences : M/S. 2019 Jan:35(1):55-61. doi: 10.1051/medsci/2018309. Epub 2019 Jan 23 [PubMed PMID: 30672459]

Konan LM, Reddy V, Mesfin FB. Neuroanatomy, Cerebral Blood Supply. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30335330]

Lipsett BJ, Alsayouri K. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Skull Foramen. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31536228]

Tajran J, Gosman AA. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Scalp. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31855392]

Kemp WJ 3rd, Tubbs RS, Cohen-Gadol AA. The innervation of the scalp: A comprehensive review including anatomy, pathology, and neurosurgical correlates. Surgical neurology international. 2011:2():178. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.90699. Epub 2011 Dec 13 [PubMed PMID: 22276233]

Westbrook KE, Nessel TA, Hohman MH, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Head and Neck: Facial Muscles. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29630261]

Chughtai KA, Nemer OP, Kessler AT, Bhatt AA. Post-operative complications of craniotomy and craniectomy. Emergency radiology. 2019 Feb:26(1):99-107. doi: 10.1007/s10140-018-1647-2. Epub 2018 Sep 25 [PubMed PMID: 30255407]

Subbarao BS, Fernández-de Thomas RJ, Eapen BC. Post Craniotomy Headache. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29493922]

Russ S, Anastasopoulou C, Shafiq I. Pituitary Adenoma. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32119338]

Khairat A, Waseem M. Epidural Hematoma. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30085524]

Simon LV, Newton EJ. Basilar Skull Fractures. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29261908]

M Das J, Munakomi S. Raccoon Sign. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31194384]