Introduction

Smallpox is the first human infectious disease to be successfully eradicated worldwide, and the World Health Assembly certified its global eradication in 1980.[1] It remains of clinical importance because of concerns about the potential for release and weaponization.[2]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Smallpox is a member of the viral family poxvirus, genus orthopoxvirus, and species variola virus. Poxviruses are the largest of the human viral pathogens and have a brick-shaped appearance on electron microscopy. Variola virus measures approximately 300 nm to 350 nm long. The poxviruses possess a linear, double-stranded DNA genome, and are unique in that their genetic makeup encodes all the proteins necessary for replication allowing them to replicate in the host cell cytoplasm.[3]

Epidemiology

Smallpox is a human disease without animal reservoirs, which became an important factor in its successful eradication. In the late 1700s, Edward Jenner successfully demonstrated that cowpox virus could vaccinate people against smallpox. Vaccinia virus eventually replaced cowpox as the viral agent used for smallpox vaccination; although genetically distinct from cowpox, the origins of vaccinia are uncertain. In the 20 century, prior to eradication, the global death toll was over 300 million. Case fatality rates were approximately 30% overall, although survivors frequently suffered significant morbidity including blindness and skin scarring. The last naturally-occurring case of smallpox was found in Somalia in 1977.[4]

Smallpox transmission occurs through airborne respiratory droplet secretions or direct contact with lesions or contaminated fomites. Infectious viral particles are released from sloughing of oropharyngeal lesions and resultant aerosolization of viral particles. Transmission can occur from the onset of lesions until all crusts have sloughed. Airborne transmission in hospital and laboratory settings has been described, and smallpox requires enhanced infection control and isolation precautions.[5]

Pathophysiology

After viral entry through the oropharynx or nasopharynx, the virus migrates to regional lymph nodes where it begins replication. An initial viremia occurs on day 3 to 4 after infection, and the virus further disseminates to the bone marrow, spleen, and additional lymph node chains. A secondary viremia occurs between day 8 to 12 after infection and coincides with the onset of fever and clinical evidence of illness. At this stage, the virus becomes localized in the oropharyngeal mucosa and small blood vessels of the dermis, resulting in the onset of rash and clinical infectiousness.[6]

History and Physical

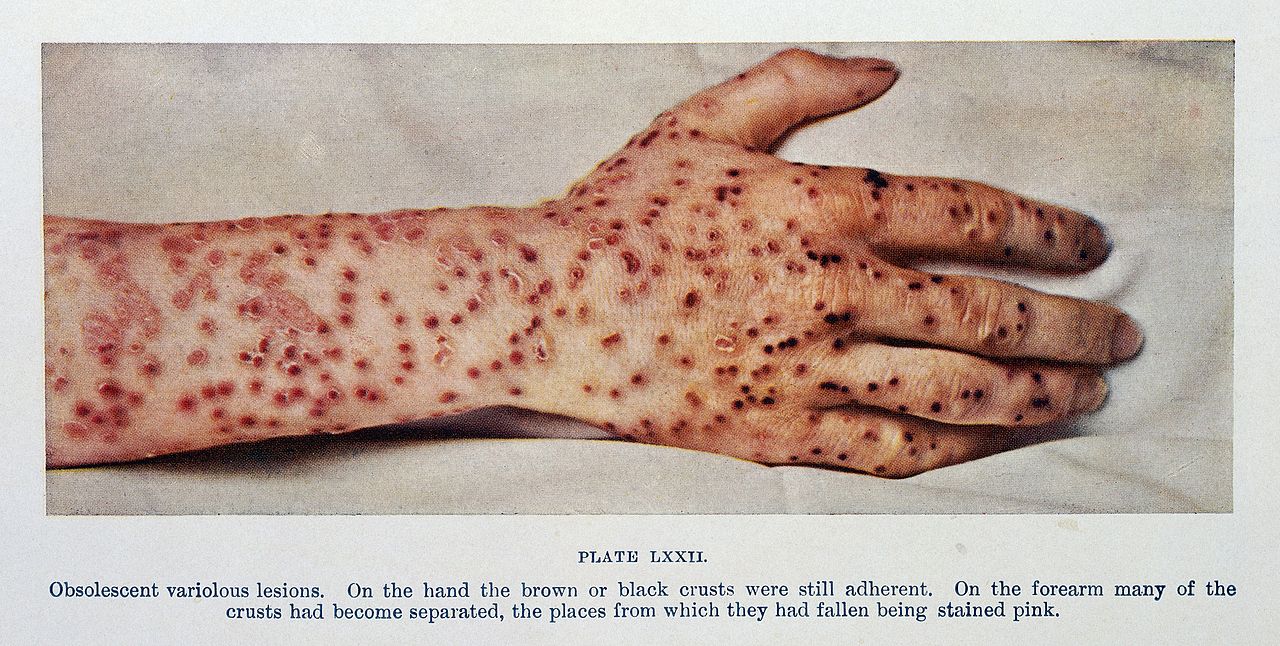

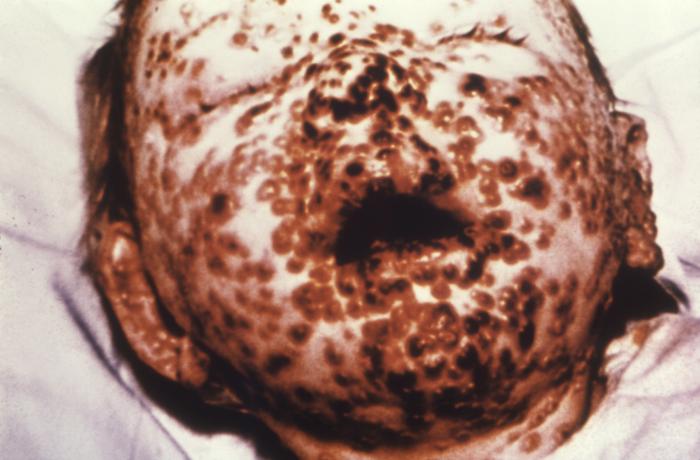

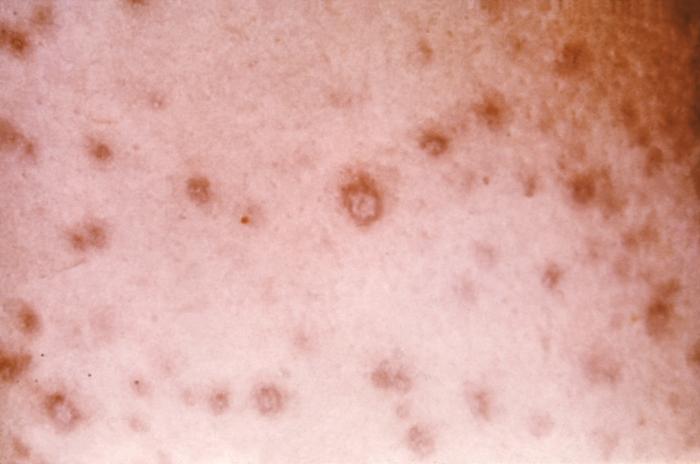

Clinical manifestations of smallpox begin with non-specific febrile prodrome including high fever, chills, abdominal pain and vomiting, headache and backache. The febrile prodrome occurs 1 to 3 days before the onset of skin lesions. The emergence of skin lesions begins on the forearms or face and then spreads to the rest of the body, with palms and soles frequently involved. Lesions are most numerous on the extremities and face with fewer lesions on the torso. Lesions on one portion of the body emerge and evolve at the same stage of development throughout the illness. Individual skin lesions change from macules to papules, to vesicles, to pustules, to crusts with approximately 48 hours elapsing between stages. Crusting of all lesions is typically complete 2 to 3 weeks after the initial onset of rash. The lesions appear deep-seated, round, firm, well-circumscribed and approximately 7 mm to 10 mm in diameter.[7][6]

Evaluation

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has developed an evaluation tool for clinicians caring for patients presenting with a rash illness that resembles smallpox based upon major and minor criteria. Major criteria for smallpox include febrile prodrome, classic lesion appearance, and lesions in the same stage of development. Minor criteria include centrifugal (distal extremities and face) distribution of the rash, the initial appearance of lesions on oral mucosa or palate, face or forearms, the presence of rash on palms and soles, slow rash evolution (1 to 2 days per stage) and toxic appearance. Based on these criteria patients are described as having a low, moderate, or high risk for smallpox with recommendations for diagnostic testing based upon classification. [8]Laboratory testing is not recommended for low or moderate risk patients in the absence of known smallpox circulation. For patients in whom testing is recommended, PCR from serum or whole blood as well as tissue samples may be recommended after public health consultation.[6][7]

Treatment / Management

Prior to eradication, supportive care was the primary treatment available. In the post-eradication era, development of anti-orthopoxvirus medical therapies remains an active area of research. In 2018, the United States approved tecovirimat as the first antiviral therapy indicated for treatment of smallpox. [9] Although the antiviral has only been evaluated fully in animal models, it has been administered to human volunteers in a safety trial, and as an emergency investigational drug to patients who developed post-vaccination complications.[9][10][11](B3)

Vaccination has been successful in the eradication of smallpox globally. There have been several smallpox vaccines developed over time, beginning with variolation, the deliberate inoculation of infectious smallpox from the pustule of an infectious person to a healthy, nonimmune contact to induce a more mild disease course. Descriptions of variolation are found from as early as 1500 BC. This practice carried significant risk including severe disease and mortality as well as the potential for community spread of infection. In 1798, Edward Jenner’s publication of his research confirming that cowpox protected against smallpox infection led to the adoption of cowpox vaccination. By 1900, cowpox was no longer the virus used for vaccination, but vaccinia virus, which is more closely related to horsepox. Vaccinia became the virus used for large-scale global vaccination programs during the 20th century, but potential risks persisted.[12]

Vaccine-associated adverse events from live vaccinia virus can be serious and include generalized vaccinia, eczema vaccinatum, progressive vaccinia, and postvaccinial encephalitis. Vaccine adverse events can also cause symptoms in others through contact with vaccine site and unintended inoculation, or from vaccinated mother to fetus.[13][14](B3)

Post-eradication, vaccine researchers have utilized improved technology to develop tissue-culture-based live vaccines, live attenuated virus vaccines, and viral subunit vaccine products. These are necessary to improve vaccine safety within the global context of an eradicated infection. Current smallpox vaccine recommendations include only personnel at increased special risk of exposure such as researchers, some healthcare workers, and some United States military personnel.[12]

Differential Diagnosis

Distinguishing smallpox from similar rashes remains an important perspective for practicing clinicians. The differential diagnosis of smallpox includes chickenpox, HSV-disseminated or eczema herpeticum, VZV-disseminated zoster, enteroviral hand-foot-mouth syndromes, drug eruptions including Stevens-Johnson or toxic epidermal necrolysis, generalized vaccinia and monkeypox.[6]

Pearls and Other Issues

Remaining variola virus stock has been restricted to the WHO Collaborating Centers on Smallpox and other Poxvirus Infections at the CDC and the Russian State Research Centre of Virology and Biotechnology (SRC VB VECTOR) labs. After the events of Sept. 11, 20001 in the United States, the concern arose for the deliberate release of the virus as an act of bioterrorism, and research for medical countermeasures including vaccines and anti-viral medications was renewed.[12]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

It is hoped no healthcare professional will ever encounter smallpox. That being said an interprofessional team of emergency nurses and clinicians, in the front lines, need to be aware of the presentation so that if it does occur, it will be reported quickly so that an appropriate response can be undertaken to minimize the outbreak. [Level V]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

This young girl in Bangladesh was infected with smallpox in 1973, Freedom from smallpox was declared in Bangladesh in December, 1977 when a WHO International Commission officially certified that smallpox had been eradicated from that country Contributed by Wikimedia Commons, James Hicks (PD-USGov-HHS-CDC)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Henderson DA. The eradication of smallpox--an overview of the past, present, and future. Vaccine. 2011 Dec 30:29 Suppl 4():D7-9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.06.080. Epub 2011 Dec 19 [PubMed PMID: 22188929]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLane JM, Poland GA. Why not destroy the remaining smallpox virus stocks? Vaccine. 2011 Apr 5:29(16):2823-4. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.02.081. Epub 2011 Mar 2 [PubMed PMID: 21376120]

Voigt EA, Kennedy RB, Poland GA. Defending against smallpox: a focus on vaccines. Expert review of vaccines. 2016 Sep:15(9):1197-211. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2016.1175305. Epub 2016 Apr 28 [PubMed PMID: 27049653]

Eyler JM, Smallpox in history: the birth, death, and impact of a dread disease. The Journal of laboratory and clinical medicine. 2003 Oct; [PubMed PMID: 14625526]

Milton DK. What was the primary mode of smallpox transmission? Implications for biodefense. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology. 2012:2():150. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00150. Epub 2012 Nov 29 [PubMed PMID: 23226686]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMoore ZS, Seward JF, Lane JM. Smallpox. Lancet (London, England). 2006 Feb 4:367(9508):425-35 [PubMed PMID: 16458769]

Breman JG, Henderson DA. Diagnosis and management of smallpox. The New England journal of medicine. 2002 Apr 25:346(17):1300-8 [PubMed PMID: 11923491]

Seward JF,Galil K,Damon I,Norton SA,Rotz L,Schmid S,Harpaz R,Cono J,Marin M,Hutchins S,Chaves SS,McCauley MM, Development and experience with an algorithm to evaluate suspected smallpox cases in the United States, 2002-2004. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2004 Nov 15; [PubMed PMID: 15546084]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGrosenbach DW, Honeychurch K, Rose EA, Chinsangaram J, Frimm A, Maiti B, Lovejoy C, Meara I, Long P, Hruby DE. Oral Tecovirimat for the Treatment of Smallpox. The New England journal of medicine. 2018 Jul 5:379(1):44-53. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1705688. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29972742]

Mucker EM, Goff AJ, Shamblin JD, Grosenbach DW, Damon IK, Mehal JM, Holman RC, Carroll D, Gallardo N, Olson VA, Clemmons CJ, Hudson P, Hruby DE. Efficacy of tecovirimat (ST-246) in nonhuman primates infected with variola virus (Smallpox). Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2013 Dec:57(12):6246-53. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00977-13. Epub 2013 Oct 7 [PubMed PMID: 24100494]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVora S, Damon I, Fulginiti V, Weber SG, Kahana M, Stein SL, Gerber SI, Garcia-Houchins S, Lederman E, Hruby D, Collins L, Scott D, Thompson K, Barson JV, Regnery R, Hughes C, Daum RS, Li Y, Zhao H, Smith S, Braden Z, Karem K, Olson V, Davidson W, Trindade G, Bolken T, Jordan R, Tien D, Marcinak J. Severe eczema vaccinatum in a household contact of a smallpox vaccinee. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2008 May 15:46(10):1555-61. doi: 10.1086/587668. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18419490]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMelamed S, Israely T, Paran N. Challenges and Achievements in Prevention and Treatment of Smallpox. Vaccines. 2018 Jan 29:6(1):. doi: 10.3390/vaccines6010008. Epub 2018 Jan 29 [PubMed PMID: 29382130]

Mota BE, Gallardo-Romero N, Trindade G, Keckler MS, Karem K, Carroll D, Campos MA, Vieira LQ, da Fonseca FG, Ferreira PC, Bonjardim CA, Damon IK, Kroon EG. Adverse events post smallpox-vaccination: insights from tail scarification infection in mice with Vaccinia virus. PloS one. 2011 Apr 15:6(4):e18924. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018924. Epub 2011 Apr 15 [PubMed PMID: 21526210]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWollenberg A,Engler R, Smallpox, vaccination and adverse reactions to smallpox vaccine. Current opinion in allergy and clinical immunology. 2004 Aug; [PubMed PMID: 15238792]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence