Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Sphincter Urethrae

Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Sphincter Urethrae

Introduction

The urethral sphincter is a muscular structure that regulates the outflow of urine from the bladder into the urethra. There are two urethral sphincters, the external and internal urethral sphincters.[1] When these muscles contract, the urethra narrows, and urination stops or slows.[1]

The urethral sphincter is critical for the maintenance of urinary continence.[2] Urinary incontinence is often associated with the pathology of the urethral sphincter and is a very common problem worldwide.[2][3] Also, normal internal urethral sphincter function is necessary for the ejaculation of semen in males.[1] The urethral sphincter muscles are located within the deep perineal pouch.[4][5][6][7]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The internal urethral sphincter is composed of smooth muscle and regulates involuntary control of urinary flow from the bladder to the urethra, while the external urethral sphincter provides voluntary regulation.[1][8] The internal urethral sphincter in men also functions to prevent the retrograde flow of semen into the bladder during ejaculation. The average length of the male urethra is about 22 cm, and in women, just 4 cm.[9]

The external sphincter in women is far more complex and intricate than in men.[1] This structure is composed of an inner mucosa with a urothelial lining, a spongy mucus-producing submucosa, a layer of smooth muscle, and an external sheath of fibroelastic connective tissue.

Contraction of the female external sphincter muscles will constrict both the urethra and the vagina.[10]

While it is easier to think of the urethral sphincters as two separate structures, with an internal smooth muscle component and an external section of striated muscle, the more accurate, modern view is that the two sphincteric areas are functionally independent, but they form a single continuous layer from the bladder neck to the perineal membrane and constitute a single urethral sphincter complex.[11][12] This leads to the modern concept that continence at rest (passive continence) is primarily, if not exclusively, a function of urethral smooth muscle, even in male post-prostatectomy patients.[11]

Embryology

In the ninth week of the fetal period, undifferentiated mesenchyme is located in the anterior part of the urethra, which develops into the external urethral sphincter.

The external urethral sphincter is also known as the rhabdosphincter, while the internal sphincter is sometimes called the lissosphincter.

Later, around the 12th week, striated muscle fibers start to develop.

The internal urethral sphincter is thought to arise from the absorption of the Wolffian duct into the bladder and urethra.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

In Males

- The inferior vesical artery supplies blood to the bladder, neck, and fundus.

- The male external urethral sphincter is in the same anatomical area as the membranous urethra, supplied by the bulbourethral artery.

- Lymphatic drainage from the proximal urethra (prostatic and bulbomembranous sections) drains into the obturator and medial external iliac lymph nodes.

In Females

- The vaginal artery replaces the inferior vesical artery to supply the bladder, neck, and fundus.

- The blood supply to the external urethral sphincter is the internal pudendal artery from the internal iliac artery.

- The vessels of the internal pudendal, which supply the area of the external urethral sphincter and the internal urethral sphincter, drain into the internal iliac vein.

- Lymphatic drainage from the proximal urethral is into the obturator, hypogastric, and external iliac lymph nodes.

Nerves

The pudendal nerve innervates the external urethral sphincter, originating from the S2 to S4 nerve roots.[17][18] Neural control of the pudendal nerve and the external urinary sphincter begins at the Onuf nucleus, a small collection of motor neurons found on the anterior horn of the S2 spinal cord segment.[19] When stimulated, it leads to constriction of the urethra.

The external urethral sphincter (or rhabdosphincter) is primarily made of striated skeletal muscle and is under voluntary control via the deep perineal branch of the pudendal nerve and nicotinic receptors.[20]

The internal urethral sphincter is composed of smooth muscle; the autonomic nervous system controls it via the hypogastric nerves and alpha-one receptors.

When the bladder is full, the parasympathetic tone increases while sympathetic activity decreases.[21] This leads to the relaxation of the internal sphincter muscle, which, along with a parasympathetic mediated detrusor contraction, allows for normal voiding and bladder emptying.[22][23]

Cauda equina syndrome is usually the result of injury, compression, or dysfunction of the nerves from L1-L5 (most often L3-L5) spinal nerve roots.[24] While detrusor overactivity may occur, the overall effect on voiding is typically urinary retention which is usually best managed by intermittent self-catheterization.[24] See the companion StatPearls reference article "Cauda Equina And Conus Medullaris Syndromes."[24]

Detrusor sphincter dyssynergia describes the clinical situation where there is a lack of coordination between detrusor muscle contractions and involuntary, inappropriate urethral sphincter closure, often caused by a lesion or dysfunction of the suprasacral spinal cord.[25] This condition is most commonly associated with spinal cord injuries, multiple sclerosis, and spinal bifida.[25] Typical treatment includes medication (diazepam, alpha-blockers), intra-sphincteric botulinum toxin A injections, intermittent self-catheterization, or sacral neuromodulation.[25] See the companion StatPearls reference article "Bladder Sphincter Dyssynergia."[25]

Muscles

The internal urethral sphincter (sometimes called the lissosphincter) consists of smooth muscle and is continuous with the bladder detrusor. The muscle fibers form a circular configuration that is continuous with the smooth muscle fibers of the bladder.

Contraction of the internal urethral sphincter stops the flow through the internal urethral orifice, blocking urine flow from the bladder. The internal urethral sphincter is made of a layer of smooth muscle surrounded by striated muscle.

The levator ani comprises three components (the pubococcygeus, puborectalis, and iliococcygeus muscles) and most of the pelvic floor musculature.[5][15]

The female external urethral sphincter is composed of striated muscle and is located distally and inferiorly to the bladder neck in women between the vaginal orifice and clitoris.[1] The female external urethral sphincter, also known as the urogenital sphincter, is located at the distal, inferior end of the urethra.[26] This sphincter is composed of three parts:[1]

- The first part is a circular muscle.

- The second part is known as the urethral compressor muscle and extends anteriorly to connect with the ischial rami.

- The third part surrounds both the vagina and urethra and is known as the urethrovaginal sphincter.

- Contraction of the urethrovaginal sphincter leads to constriction of both the urethra and vagina.

- Skene glands are a pair of mucus glands located on either side of the distal end of the female urethra.

- They are also sometimes called the lesser vestibular glands.

- They secrete lubrication to the urethral meatus.

- They are homologs of the male prostate gland.

In males, the external urethral sphincter is located at the same level as the membranous urethra and is composed of circular muscle fibers.[1]

- The external urethral sphincter is continuous with the isthmus of the prostate.

- The external urethral sphincter is located between the pudendal canals below the pelvic diaphragm.

- The external urethral sphincter originates at the ischiopubic ramus and inserts with muscular fibers on the opposite side, the perineal body anteriorly, and the anococcygeal ligament posteriorly.

Surgical Considerations

Urinary incontinence can occur after pelvic surgeries and childbirth. This is a common complication, especially in prostate cancer treatment in men and childbirth in women. Urethral sphincter incompetence and dysfunction are among the most important factors for post-radical prostatectomy urinary incontinence, although bladder dysfunction may also play a role. Rates of postoperative urinary incontinence vary widely by surgeon skill and experience, but good results would still report a urinary leakage rate of between 4% to 8% of patients.[27][28][29]

Vaginal childbirth can result in trauma to pelvic ligaments, the levator ani, pelvic floor muscles, the endopelvic fascia, and other related structures.[30] Levator ani injuries are common after childbirth, occurring in 13% to 36% of women giving birth vaginally and almost 50% of those where forceps were used.[31][32][33] Such injuries can include avulsion or stretch trauma to the levator ani, which increases the risk of subsequent development of pelvic organ prolapse.[32] Damage to the levator ani contributes to increased urethral mobility, lack of pelvic support, and an increased risk of urinary stress incontinence, especially if the bladder neck area is affected.[34][35]

The pudendal nerve, which innervates the female external sphincter, is susceptible to childbirth injury as it passes between the sacrotuberous and sacrospinous pelvic ligaments.[36]

Risk factors for pudendal nerve injury during childbirth include multiparity, extended duration of second-stage labor, third or fourth-degree perineal tears, higher infant birth weight, and larger head circumference.[36]

Clinical Significance

A malfunction of the urethral sphincters can lead to various disorders of the lower urinary tract, usually some form of incontinence. Urinary incontinence is at least twice as prevalent in women as in men.[37] As women age, the risk of urinary incontinence tends to increase. Besides aging, this is due to constitutional issues, decreased mobility, genetic predisposing factors, vaginal childbirth history, pelvic floor muscle damage, pelvic organ prolapse, neuropathy, diabetes, hormonal changes, dementia, obesity, and menopause.[38]

There are five basic types of urinary incontinence.[3]

- Stress incontinence is characterized by loss of urine during sneezing, coughing, or intense physical activity.[3]

- Urge incontinence is associated with the sudden, uncontrollable need to urinate, which leads to an immediate loss of urine, commonly associated with detrusor overactivity.[39]

- Overflow incontinence is frequent, intermittent dribbling of urine because the bladder is full and the patient is in urinary retention due to detrusor hypotonicity or bladder outlet obstruction.[40][41]

- Functional incontinence is the inability to reach the restroom promptly due to mental or physical issues such as an obstruction or a long line to use the toilet.[3]

- Mixed incontinence is a mixture of any of these types of incontinence, although one type will typically be more bothersome to the patient.[42]

Stress incontinence is the most common type of urinary leakage and accounts for up to 88% of all incontinent patients.[43] This occurs because there is a problem with the closing mechanism at the urinary tract outlet due to issues with support, direct trauma, muscle tone, scarring, damage to the levator ani, neurological dysfunction, or similar disorders.

A bladder stress test can be used in patients suspected of having stress incontinence.

To do the test in women, the bladder must be at least partially full. The urethra is visualized by separating the labia while having the patient cough or Valsalva. If there is leakage of urine from the urethra, then she is confirmed to have stress incontinence. Pelvic floor exercises such as Kegel's and physical therapy are often very effective in controlling leakage from stress incontinence.[44] Support devices (pessaries), pharmacotherapy, and surgery (pelvic sling procedures) are used when simpler measures fail.

Urge incontinence can be particularly bothersome to patients; it may be caused by neuropathy, infection, caffeine effect, or an intrinsic bladder disorder. If the bladder empties well, pharmacotherapy can be very effective. Intractable cases can be treated with sacral neuromodulation, tibial nerve stimulation, or Botulinum toxin A detrusor injections.[39]

Overflow incontinence is due to urinary retention. This may be caused by neuropathy, diabetes, prostate enlargement, detrusor hypotonicity, overactive bladder and detrusor overactivity, bladder outlet obstruction, or similar problems. The condition is managed by medication, surgery, or urethral catheterization (self-intermittent or permanent) as appropriate.[40][41]

Functional incontinence is most often due to a combination of factors such as dementia, communication issues, detrusor hypotonicity, bladder overactivity, weakened pelvic floor muscles, atrophic vaginitis, bladder prolapse, mobility issues, arthritis, etc. Functional incontinence is treated with a variety of methods that are individualized for each patient but include:

- Absorbent pads

- Avoidance of bladder irritants such as caffeine

- Bedside commode

- Condom catheters

- Clothing that is easier to remove

- Cunningham clamps

- Removing obstructions to the restroom, such as furniture

- Scheduled voiding

The treatment for urinary incontinence varies depending on the cause. However, initial treatment for most types of urinary incontinence includes lifestyle modifications and pelvic floor muscle exercises. Surgery (such as a urethral sling procedure, artificial sphincter, or urethral compression implants) is reserved for selected refractory cases where less invasive treatments are unsatisfactory, and the expected benefit outweighs the risks of anesthesia and surgical complications.[3]

There are also non-surgical treatments.[3] These include:

- Absorbent pads

- Bedside commode

- Bladder training

- Cunningham clamps

- Dietary modifications (avoidance of caffeine)

- Elimination of constipation

- Hormonal therapy (estrogen vaginal cream)

- Kegel exercises

- McQuire urinal

- Overnight urinary collection device (for women)

- Pharmacotherapy

- Physical therapy

- Scheduled voiding

- Smoking cessation

- Vaginal support (pessary)

- Weight loss

Other Issues

Prostate surgery, such as transurethral resection of the prostate, can permanently damage or destroy the male internal sphincter, which has little effect on urinary continence but results in obligatory retrograde ejaculation.[45]

Media

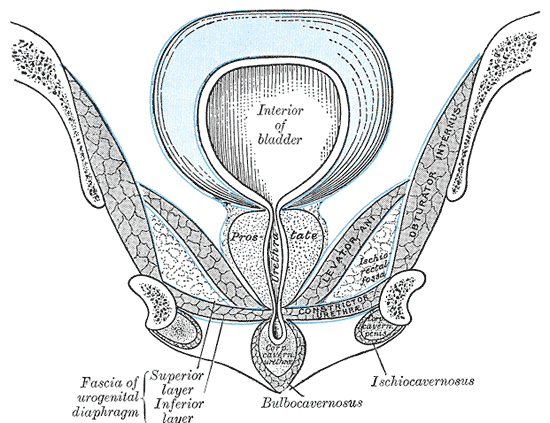

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

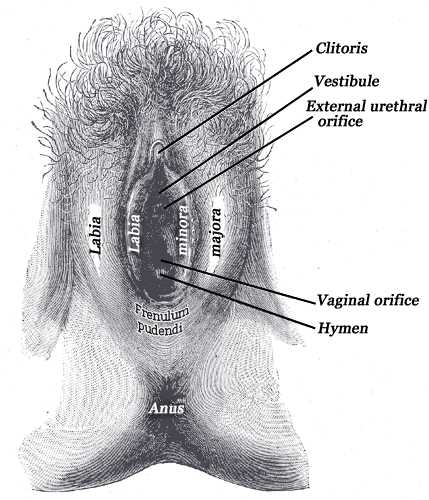

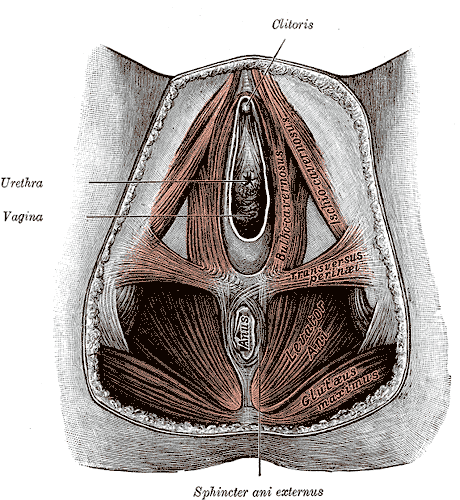

Female Perineum. The female perineum includes the clitoris, urethra, vagina, sphincter ani externus, anus, gluteus maximus, levator ani, and transversus perinei.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

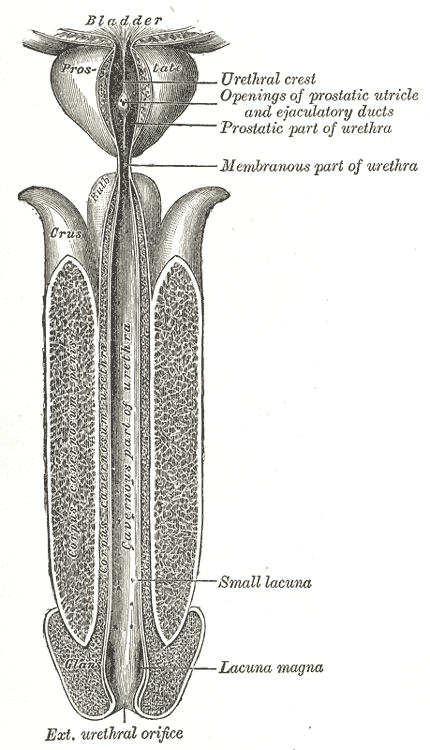

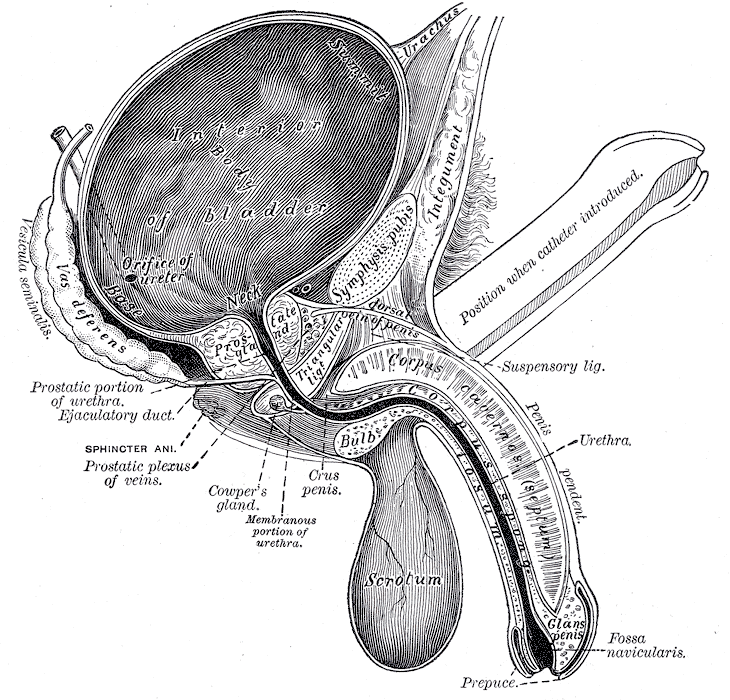

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Jung J, Ahn HK, Huh Y. Clinical and functional anatomy of the urethral sphincter. International neurourology journal. 2012 Sep:16(3):102-6. doi: 10.5213/inj.2012.16.3.102. Epub 2012 Sep 30 [PubMed PMID: 23094214]

Heesakkers JP, Gerretsen RR. Urinary incontinence: sphincter functioning from a urological perspective. Digestion. 2004:69(2):93-101 [PubMed PMID: 15087576]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTran LN, Puckett Y. Urinary Incontinence. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32644521]

Shermadou ES, Rahman S, Leslie SW. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Bladder. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30285360]

Bordoni B, Sugumar K, Leslie SW. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Pelvic Floor. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29489277]

Merrill SB, Boorjian SA, Thompson RH, Psutka SP, Cheville JC, Thapa P, Tollefson MK, Frank I. Oncologic surveillance following radical cystectomy: an individualized risk-based approach. World journal of urology. 2017 Dec:35(12):1863-1869. doi: 10.1007/s00345-017-2068-7. Epub 2017 Jul 6 [PubMed PMID: 28685181]

Bolla SR, Hoare BS, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Deep Perineal Space. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30855860]

Aanestad O, Flink R. Urinary stress incontinence. A urodynamic and quantitative electromyographic study of the perineal muscles. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica. 1999 Mar:78(3):245-53 [PubMed PMID: 10078588]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKohler TS, Yadven M, Manvar A, Liu N, Monga M. The length of the male urethra. International braz j urol : official journal of the Brazilian Society of Urology. 2008 Jul-Aug:34(4):451-4; discussion 455-6 [PubMed PMID: 18778496]

Oelrich TM. The striated urogenital sphincter muscle in the female. The Anatomical record. 1983 Feb:205(2):223-32 [PubMed PMID: 6846873]

Koraitim MM. The male urethral sphincter complex revisited: an anatomical concept and its physiological correlate. The Journal of urology. 2008 May:179(5):1683-9. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.01.010. Epub 2008 Mar 17 [PubMed PMID: 18343449]

Brooks JD, Chao WM, Kerr J. Male pelvic anatomy reconstructed from the visible human data set. The Journal of urology. 1998 Mar:159(3):868-72 [PubMed PMID: 9474171]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWu EH, De Cicco FL. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Male Genitourinary Tract. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32965962]

Singh O, Bolla SR. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Prostate. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31082031]

Gowda SN, Bordoni B. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Levator Ani Muscle. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32310538]

Nguyen JD, Duong H. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Female External Genitalia. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31613483]

Juenemann KP, Lue TF, Schmidt RA, Tanagho EA. Clinical significance of sacral and pudendal nerve anatomy. The Journal of urology. 1988 Jan:139(1):74-80 [PubMed PMID: 3275803]

Zvara P, Carrier S, Kour NW, Tanagho EA. The detailed neuroanatomy of the human striated urethral sphincter. British journal of urology. 1994 Aug:74(2):182-7 [PubMed PMID: 7921935]

Rajaofetra N, Passagia JG, Marlier L, Poulat P, Pellas F, Sandillon F, Verschuere B, Gouy D, Geffard M, Privat A. Serotoninergic, noradrenergic, and peptidergic innervation of Onuf's nucleus of normal and transected spinal cords of baboons (Papio papio). The Journal of comparative neurology. 1992 Apr 1:318(1):1-17 [PubMed PMID: 1374763]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKinter KJ, Newton BW. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Pudendal Nerve. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32134612]

Sam P, Nassereddin A, LaGrange CA. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Bladder Detrusor Muscle. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29489195]

Ahmed DG, Mohamed MF, Mohamed SA. Superior hypogastric plexus combined with ganglion impar neurolytic blocks for pelvic and/or perineal cancer pain relief. Pain physician. 2015 Jan-Feb:18(1):E49-56 [PubMed PMID: 25675070]

Tong XK, Huo RJ. The anatomical basis and prevention of neurogenic voiding dysfunction following radical hysterectomy. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 1991:13(2):145-8 [PubMed PMID: 1925917]

Rider LS, Marra EM. Cauda Equina and Conus Medullaris Syndromes. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30725885]

Feloney MP, Leslie SW. Bladder Sphincter Dyssynergia. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32965837]

Hudson CN, Sohaib SA, Shulver HM, Reznek RH. The anatomy of the perineal membrane: its relationship to injury in childbirth and episiotomy. The Australian & New Zealand journal of obstetrics & gynaecology. 2002 May:42(2):193-6 [PubMed PMID: 12069149]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSchiøtz HA. Periurethral injection therapy in women with stress incontinence. Tidsskrift for den Norske laegeforening : tidsskrift for praktisk medicin, ny raekke. 2019 Jan 29:139(2):. doi: 10.4045/tidsskr.18.0185. Epub 2019 Jan 24 [PubMed PMID: 30698387]

Dumoulin C, Pazzoto Cacciari L, Mercier J. Keeping the pelvic floor healthy. Climacteric : the journal of the International Menopause Society. 2019 Jun:22(3):257-262. doi: 10.1080/13697137.2018.1552934. Epub 2019 Jan 17 [PubMed PMID: 30653374]

Nalbant İ, Tuygun C, Öztürk U, Göktuğ HNG, Karakoyunlu AN, Selmi V, İmamoğlu MA. Do the etiological factors in artificial urinary sphincter reimplantation cases affect success and complications? Turkish journal of medical sciences. 2018 Dec 12:48(6):1263-1267. doi: 10.3906/sag-1805-150. Epub 2018 Dec 12 [PubMed PMID: 30541256]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTunn R, Goldammer K, Neymeyer J, Gauruder-Burmester A, Hamm B, Beyersdorff D. MRI morphology of the levator ani muscle, endopelvic fascia, and urethra in women with stress urinary incontinence. European journal of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology. 2006 Jun 1:126(2):239-45 [PubMed PMID: 16298035]

Shek KL, Dietz HP. Intrapartum risk factors for levator trauma. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 2010 Nov:117(12):1485-92. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02704.x. Epub 2010 Aug 25 [PubMed PMID: 20735379]

Caudwell-Hall J, Kamisan Atan I, Martin A, Guzman Rojas R, Langer S, Shek K, Dietz HP. Intrapartum predictors of maternal levator ani injury. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica. 2017 Apr:96(4):426-431. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13103. Epub 2017 Mar 10 [PubMed PMID: 28117880]

Memon HU, Blomquist JL, Dietz HP, Pierce CB, Weinstein MM, Handa VL. Comparison of levator ani muscle avulsion injury after forceps-assisted and vacuum-assisted vaginal childbirth. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2015 May:125(5):1080-1087. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000825. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25932835]

Shek KL, Pirpiris A, Dietz HP. Does levator avulsion increase urethral mobility? European journal of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology. 2010 Dec:153(2):215-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2010.07.036. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20810202]

DeLancey JO. The pathophysiology of stress urinary incontinence in women and its implications for surgical treatment. World journal of urology. 1997:15(5):268-74 [PubMed PMID: 9372577]

Snooks SJ, Swash M, Henry MM, Setchell M. Risk factors in childbirth causing damage to the pelvic floor innervation. International journal of colorectal disease. 1986 Jan:1(1):20-4 [PubMed PMID: 3598309]

Parks AG. Royal Society of Medicine, Section of Proctology; Meeting 27 November 1974. President's Address. Anorectal incontinence. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 1975 Nov:68(11):681-90 [PubMed PMID: 1197295]

van Geelen H, Sand PK. The female urethra: urethral function throughout a woman's lifetime. International urogynecology journal. 2023 Jun:34(6):1175-1186. doi: 10.1007/s00192-023-05469-6. Epub 2023 Feb 9 [PubMed PMID: 36757487]

Nandy S, Ranganathan S. Urge Incontinence. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 33085319]

Leslie SW, Rawla P, Dougherty JM. Female Urinary Retention. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30860732]

Dougherty JM, Aeddula NR. Male Urinary Retention. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30860734]

Harris S, Riggs J. Mixed Urinary Incontinence. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30480967]

Sandvik H, Hunskaar S, Vanvik A, Bratt H, Seim A, Hermstad R. Diagnostic classification of female urinary incontinence: an epidemiological survey corrected for validity. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 1995 Mar:48(3):339-43 [PubMed PMID: 7897455]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHuang YC, Chang KV. Kegel Exercises. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32310358]

Leslie SW, Chargui S, Stormont G. Transurethral Resection of the Prostate. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32809719]