Introduction

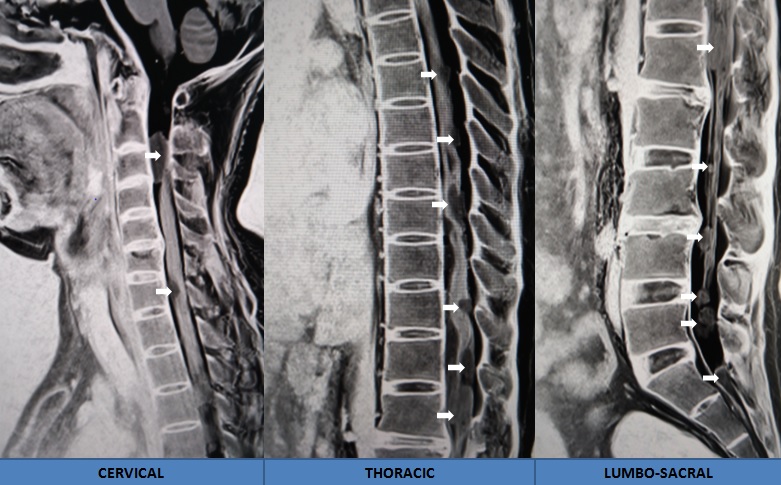

Spinal metastases are the most common tumors of the spine, comprising approximately 90% of masses encountered with spinal imaging. Spinal metastases are more commonly found as bone metastasis, although they are not limited to bone metastasis, and approximately 20% present with symptoms of spinal canal invasion and cord compression. Within the spinal column, metastasis is more commonly found in the thoracic region, followed by the lumbar region, while the cervical region is the least likely place professionals find metastasis [1].

While evaluating spinal metastasis on MRI imaging, a defining feature of these lesions is the sparing of intervertebral disc space. This disc space is almost always involved during infection. Metastatic diseases to the spine spread through several different routes which include venous hematogenous spread versus the arterial spread, direct tumor extension, and lastly lymphatic spread. Among the routes mentioned above, hematogenous spread through Batson’s plexus system is the most common pathway for tumor embolization and spinal invasion. The following summary emphasizes the essential knowledge necessary to have while treating patients with spinal metastasis [2][3].

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The most common primary malignancies predominantly metastasizing to the spine include the following tumors in descending order: breast (21%), lung (19%), prostate (7.5%), renal (5%), gastrointestinal (4.5%), and thyroid (2.5%). While all tumors can seed to the spine, the cancers mentioned above metastasize to the spinal column early in the disease process. While the exact mechanism and gene expression necessary for tumor invasion of the spine is a focus of continuous active research, the presence of certain factors like RANK and RANKL (receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa beta (NFkB ligand)), which interact with receptors to activate osteoclastic cells, appears to play a central role in setting an island of invasion.

Epidemiology

Spinal metastasis is a common condition encountered by practitioners while treating oncologic patients. In a study of post-mortem cadavers, the examination of cancer patients with known primary the prevalence of spinal metastasis was as high as 70% to 90% for breast and prostate as the primary types of cancer. Morbidity related to spinal metastasis is related to excruciating back pain requiring high doses of narcotic medications for management, pathological bone fractures, hypercalcemia, and spinal cord compression due to the invasion of epidural space. Rarely spinal metastasis will seed inside the spinal cord itself with no apparent bone involvement. In these cases, when there is no known history of primary cancer, the diagnosis of metastatic lesions becomes difficult, and often the correct diagnosis is determined after pathology confirms the type of tumor.

Pathophysiology

The general spread of metastases involves hematogenous spreading to the center of the vertebral body. Through an initial interaction between tumors associated factors and intrinsic bone cells like osteoclasts, a nidus of invasion is established. More commonly the tumor spreads backward often involving pedicles, which is an important point of understanding for surgical management of spinal metastasis that would require spinal stabilization. Due to this fact, screw fixation through the involved pedicles often is nonoptimal and requires extending fusion of several segments above and below the lesion. Commonly, the blood supply to the metastatic nidus comes from pedicular arteries making selective embolization through interventional procedures a viable option. Further understanding of the interaction between invading metastasis and surrounding bone cells and factors produced like IL-6, IL-1, TGF-beta and RANK/RANKL have offered chemical therapy in the treatment of painful bone metastasis, especially breast and prostate as known primaries. A complete description of the mechanisms and factors involved is outside the scope of this short clinically focused review.

History and Physical

Pain is the most common presenting complaint in patients with spinal metastasis. A high clinical suspicion should be present in any oncologic patient that presents with neck or back pain. While pain is not the most fearsome or morbid symptom of spinal metastasis, it is the most common initial symptom requiring evaluation from the treating physician. In addition to being an initial presenting symptom, neck and back pain in metastasis is quite often localized requiring further diagnostic imaging on a patient that cannot undergo complete imaging of the spine. The pain is aching and deep, often occurs at night, and wakes the patient from sleep. Also, if nerve involvement has occurred which would suggest a greater extension of tumor, the pain is sharp and shooting in a specific dermatomal distribution. When the tumor has extended inside the spinal canal, motor, and sensory weakness may become permanent and more worrisome. The defining concept for the treatment of spinal metastasis includes the degree of weakness and extension of the deficit. The more severe the deficit is upon presentation, the worse the chances are for recovery. Also, time-lapse from deficit progression to the physician identifying cause determines the possibility and chances for recovery.

Evaluation

The simplest test often available to evaluate an oncologic patient presenting with neck or back pain is an x-ray of the spinal column. Plain anterior and posterior (AP) and lateral images are often non-sensitive or specific and require at least 50% bone erosion before an abnormality can be observed. Spine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the gold standard for evaluating these lesions. MRI would show extension, levels involved, and canal compromise, as well as provided clues to the etiology of the metastasis. However, this is not always possible, for example, when a patient has an implanted pacemaker or internal defibrillator. Myelography associated with or without computed tomography (CT) imaging should be considered in patients that are not candidates for MRI. Myelography provides the advantage of sending cerebrospinal fluid for pathology evaluation, but it has significant limitations when a lesion completely occludes the canal. In these cases, multiple spinal injections of contrast might be required to bypass the level of obstruction. Positron Emission Tomography (PET) scan is another modality that is sensitive but offers poor anatomical localization.

Treatment / Management

If metastasis involves multiple bony structures with no canal compromise or associated bone fracture, these patients can be managed without surgery. However, it is important to involve a spine surgical oncologist in order to get advice regarding spinal instability related to multiple metastases to the spine. However, most patients with multiple spinal metastases and normal neurological examinations may benefit primarily from radiation therapy and chemotherapy. If tissue for pathologic diagnosis is necessary and there is no primary or easily reachable metastasis with any other route, a patient could benefit from an image-guided biopsy of the bone lesion. Open diagnosis is very rarely necessary after several attempts at obtaining a sample through a needle biopsy.[4][5][6](A1)

When a tumor involves the spinal canal, then treatment strategy changes significantly, and surgical consultation should be immediate as these patients can progress to becoming bed-bound within days. Studies have shown that paralysis due to metastatic spine disease significantly shortens the life expectancy of cancer patients. On the other hand, surgical intervention of patients with acute paralysis due to spinal cord compression from the metastatic disease will significantly reduce mortality and morbidity associated with acute paralysis [7][8]. (A1)

Depending upon rapidity and seriousness of neurologic compromise, treatment of these patients may involve the addition of steroids. Dexamethasone has been shown in clinical trials to decrease pain and improve symptoms. However, the exact dose that would benefit the patient the most is not known. In one study comparing bolus dose of 100 mg dexamethasone with 10 mg of dexamethasone bolus initial injection, no significant clinical benefit was observed with the higher dose. A good starting dose would be a bolus dose of 10 mg IV followed by a maintenance dose of 4 mg every six hours tapered over two weeks as the clinical scenario allows. Immediate imaging should be obtained to evaluate extension and possible surgical intervention.

If the suspicion is low for very radiosensitive tumor, if there is complete paralysis that has been present for more than 24 hours or the expected survival of the patient is less than three or four months, surgical intervention is warranted. Further treatment after surgery should involve a multidisciplinary approach of chemotherapy and focused radiation. Radiation therapy usually involves 30 Gy to 40 Gy in a ten-treatment session. Wound closure becomes a concern post radiation and chemotherapy, and the patient should be followed closely to identify wound breakdown and repair promptly.[9][10]

The current algorithm for the treatment of spinal metastasis is based on the NOMS (Neurologic, Oncologic, Mechanical, Systemic) framework. The neurologic component of this framework includes the evaluation of the grade of epidural spinal cord compression (ESCC) on MRI and neurological status of patient (presence of myelopathy), oncologic component describes the radiosensitivity of the primary tumor, mechanical component involves the mechanical stability of the spinal column, as evaluated by the spinal instability neoplastic score (SINS); and systemic component describes the general systemic condition of the patient, i.e, the ability to tolerate surgery. Based on these parameters, the broad treatment categories of these patients include conventional external beam radiation therapy (cEBRT) alone or with stabilization, spinal stereotactic radiation therapy (SSRS) alone or with stabilization or as hybrid approach following separation surgery; or decompression and surgical stabilization.

Differential Diagnosis

The major differential diagnoses for spinal metastases include

- Primary spinal tumors including myeloma, plasmacytoma, lymphoma, and sarcoma

- Spinal infections - Pyogenic and granulomatous (including tuberculosis)

Prognosis

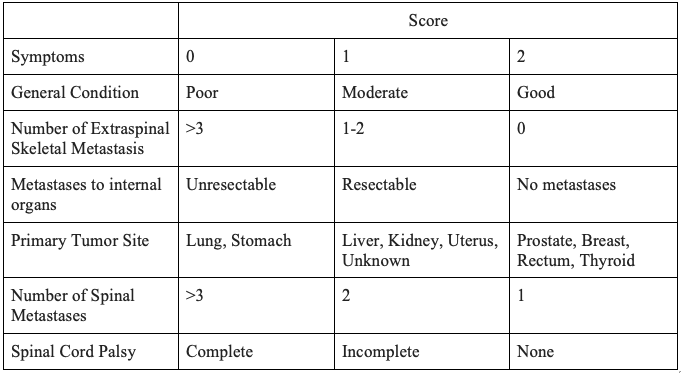

The prognosis of spinal metastasis is based on multiple factors, including the general condition of the patient, primary malignancy, presence of other visceral or skeletal or spinal metastases and neurological status.

Complications

The major complications of spinal metastasis include:

1. Pathological fracture and collapse

2. Spinal cord or other neural element injuries

3. Bleeding

4. Resistance to treatment

6. Tumor recurrence

7. Infections secondary to immunosuppressed state

Deterrence and Patient Education

1. The patient should be aware of the possibility of a pathological collapse of the involved vertebrae, and therefore bracing or external immobilizers may sometimes be recommended (apart from surgical stabilization procedures) by the treating clinicians. Strict compliance with physician recommendations is very important in such scenarios.

2. The prognosis for neurological recovery is dependent on the duration and severity of deficit; and therefore in situations of compromised neurological status, the importance of early consultation with specialist spine surgeons can not be understated.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Patients with spinal metastases are best managed with an interprofessional team that includes an oncologist, radiation consultant, radiologist, pathologist, pain specialist, neuro/orthopedic surgeon, and palliative care nurses. Most of these patients have a shortened life expectancy and aggressive procedures are usually not warranted. Both pain service and palliative care should be involved early in the care. The key is to ensure that the patient has a good quality of life.[11]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Mundy GR. Metastasis to bone: causes, consequences and therapeutic opportunities. Nature reviews. Cancer. 2002 Aug:2(8):584-93 [PubMed PMID: 12154351]

Chamberlain MC, Sloan A, Vrionis F, Cancer Care Ontario Practice Guidelines Initiative's Neuro-Oncology Disease Site Group. Systematic review of the diagnosis and management of malignant extradural spine cord compression: The Cancer Care Ontario Practice Guidelines Initiative's Neuro-Oncology Disease Site Group. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2005 Oct 20:23(30):7750-1; author reply 7751-2 [PubMed PMID: 16234541]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLoblaw DA, Perry J, Chambers A, Laperriere NJ. Systematic review of the diagnosis and management of malignant extradural spinal cord compression: the Cancer Care Ontario Practice Guidelines Initiative's Neuro-Oncology Disease Site Group. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2005 Mar 20:23(9):2028-37 [PubMed PMID: 15774794]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAielli F, Ponzetti M, Rucci N. Bone Metastasis Pain, from the Bench to the Bedside. International journal of molecular sciences. 2019 Jan 11:20(2):. doi: 10.3390/ijms20020280. Epub 2019 Jan 11 [PubMed PMID: 30641973]

Kam TY, Chan OSH, Hung AWM, Yeung RMW. Utilization of stereotactic ablative radiotherapy in oligometastatic & oligoprogressive skeletal metastases: Results and pattern of failure. Asia-Pacific journal of clinical oncology. 2019 Mar:15 Suppl 2():14-19. doi: 10.1111/ajco.13115. Epub 2019 Mar 12 [PubMed PMID: 30859749]

Yang XG, Lun DX, Hu YC, Liu YH, Wang F, Feng JT, Hua KC, Yang L, Zhang H, Xu MY, Zhang HR. Prognostic effect of factors involved in revised Tokuhashi score system for patients with spinal metastases: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. BMC cancer. 2018 Dec 13:18(1):1248. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-5139-2. Epub 2018 Dec 13 [PubMed PMID: 30545326]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePatchell RA, Tibbs PA, Regine WF, Payne R, Saris S, Kryscio RJ, Mohiuddin M, Young B. Direct decompressive surgical resection in the treatment of spinal cord compression caused by metastatic cancer: a randomised trial. Lancet (London, England). 2005 Aug 20-26:366(9486):643-8 [PubMed PMID: 16112300]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencevan den Bent MJ. Surgical resection improves outcome in metastatic epidural spinal cord compression. Lancet (London, England). 2005 Aug 20-26:366(9486):609-10 [PubMed PMID: 16112282]

Le R, Tran JD, Lizaso M, Beheshti R, Moats A. Surgical Intervention vs. Radiation Therapy: The Shifting Paradigm in Treating Metastatic Spinal Disease. Cureus. 2018 Oct 3:10(10):e3406. doi: 10.7759/cureus.3406. Epub 2018 Oct 3 [PubMed PMID: 30533340]

Osborn VW, Lee A, Yamada Y. Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy for Spinal Malignancies. Technology in cancer research & treatment. 2018 Jan 1:17():1533033818802304. doi: 10.1177/1533033818802304. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30343661]

Bollen L, Dijkstra SPD, Bartels RHMA, de Graeff A, Poelma DLH, Brouwer T, Algra PR, Kuijlen JMA, Minnema MC, Nijboer C, Rolf C, Sluis T, Terheggen MAMB, van der Togt-van Leeuwen ACM, van der Linden YM, Taal W. Clinical management of spinal metastases-The Dutch national guideline. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990). 2018 Nov:104():81-90. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2018.08.028. Epub 2018 Oct 15 [PubMed PMID: 30336360]