Introduction

The pathogen Streptococcus agalactiae represents group B Streptococcus (GBS). The commonly used term of group B streptococcus or GBS is based on Lancefield grouping that takes into account specific cell wall carbohydrate antigen. It is a common colonizer of the genital and gastrointestinal tracts. GBS colonization in pregnant women is a major risk factor for neonatal and infant infection.[1]

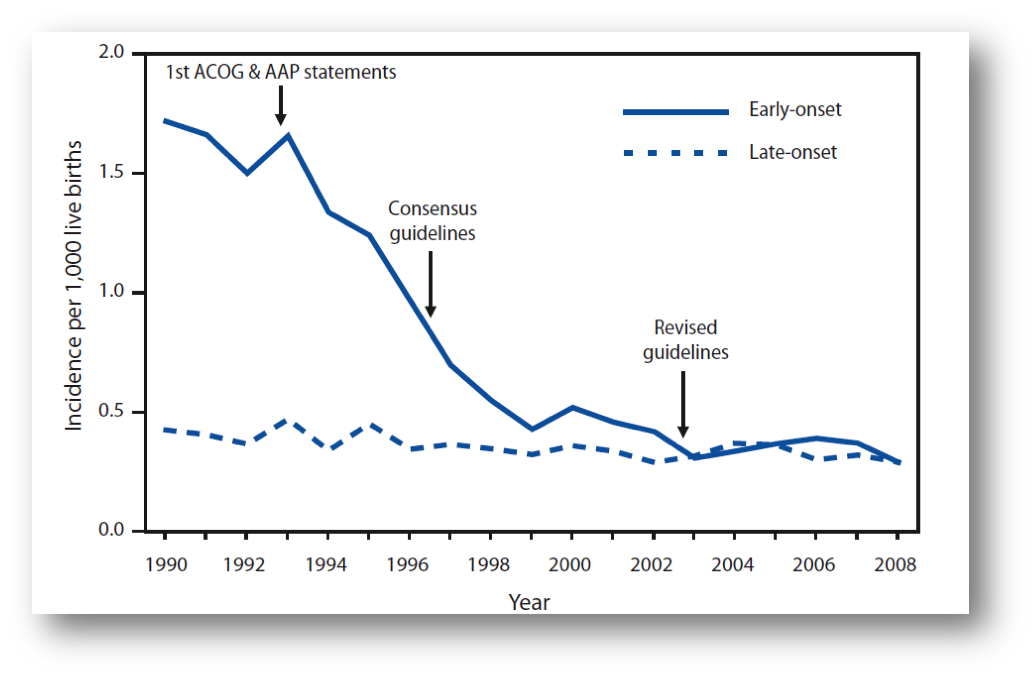

The widespread screening of pregnant women for this organism in the third trimester and subsequent antibiotic prophylaxis for maternal colonization has dramatically reduced the incidence of early-onset neonatal disease from 1.7 cases per 1000 live births in the early 1990s to 0.22 cases per 1000 live births in 2017. Direct medical costs of neonatal disease before prevention were $294 million annually.

This chapter will discuss different aspects of GBS infection in neonates and infants and pregnant women and the elderly.

History: Edmond Nocard first recognized this pathogen in 1887 as a source of bovine mastitis that resulted in agalactia or lack of milk production. Decades later, S. agalactiae gained recognition as a human pathogen responsible for infections, most commonly in pregnant women and newborns. However, the significance of this organism was not discovered until 1938, when Fry described three fatal cases of postpartum sepsis. Numerous reports continued to ascribe neonatal infections to this pathogen until the 1970s, when GBS emerged as the predominant organism causing bacteremia and meningitis in newborns and young infants less than three months old.[2] GBS is also an occasional cause of infections in postpartum women (endometritis) and individuals with impaired immune systems, in whom the organism may cause septicemia or pneumonia.[3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

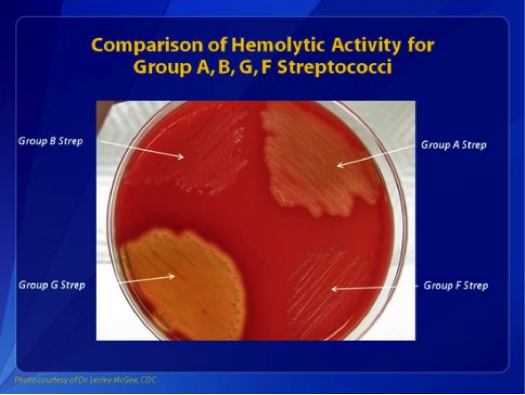

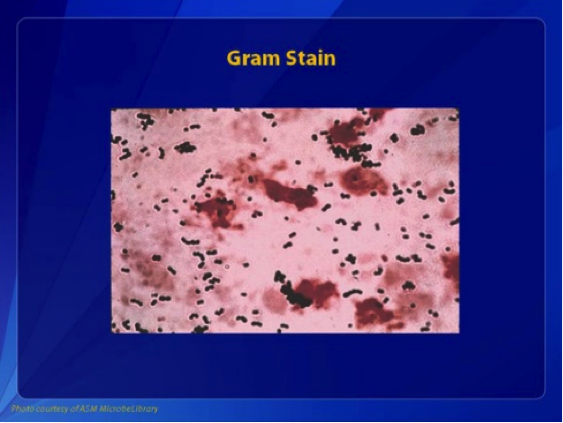

Pathogen characteristics: GBS is a gram-positive, catalase-negative organism that appears as cocci in pairs and chains on gram stain (see Image. Gram Stain, Group B Streptococcus). When grown on blood agar, they appear as small colorless colonies that cause beta-hemolysis or complete hemolysis (see Image. Comparisons of Hemolytic Activity for Groups A, B, G, and F Streptococci). This is because S. agalactiae forms a toxin known as, which causes complete lysis of the hemoglobin in RBCs.[4]

The group B specific cell wall carbohydrate antigen is common to all strains of GBS, and a surface capsular polysaccharide allows classification into types Ia, Ib, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, VIII, and IX (Lancefield classification scheme). A surface protein antigen, C protein, with alpha and beta components, is common to all Ib strains, to 30% of type Ia strains, to 60% of type II strains, and to some type IV, V, and VI strains.

Another surface component is a pilus that facilitates attachment to mucosal surfaces. The hypervirulent clonal complex ST-17 of type III has a tropism for meninges and typically is present among invasive but not colonizing neonatal isolates.

Virulence: Streptococcus agalactiae has several virulence factors that help it attach to the host cells and evade the immune system.[1][5]

- This bacterium is encapsulated by a polysaccharide layer rich in sialic acid, which is a substance also found in human cells. Thus, inexperienced immune cells in a newborn may confuse S. agalactiae for self-cells, allowing them to survive inside the body. A type-specific capsular polysaccharide is released from cells, and the amount elaborated has been correlated with virulence.

- The capsule also has pili, which are hair-like structures that help the bacteria attach to a host cell.

- Furthermore, S. agalactiae makes beta-hemolysin, a pore-forming toxin that destroys the host’s red blood cells resulting in hemolysis.

- GBS produces several bacterial products. Most strains possess C5a-ase, an enzyme of the serine esterase class that inactivates complement component C5a.[6] This C5a is a potent chemoattractant for neutrophils. This GBS enzyme helps the bacteria evade the host immune system by hindering the accumulation of neutrophils at the infection site.

GBS colonization: GBS can be found colonizing normal gastro-intestinal and genitourinary flora in up to one-third of healthy asymptomatic women. Several factors associated with a higher risk of colonization include African American ethnicity, obesity, multiple sexual partners, male-to-female oral sex, frequent sexual intercourse, tampon use, and infrequent hand washing. Pregnant women colonized with GBS can spread the bacteria to their infants before or during childbirth. The acquisition of neonatal GBS presumably occurs either by ascending transmission through ruptured membranes or from contact with the organism in the genital tract during vaginal deliveries.

Research has also described horizontal transmission from mothers or other nosocomial and community contacts.[7] Research studies investigating the causes of late-onset GBS disease propose an acquired fecal-oral route of transmission. Whether late-onset disease results from an exogenous source, such as breast milk, or established colonization, or both, remains unclear.

In addition to newborn infants, GBS can also cause invasive infections in those with a weakened immune system, such as pregnant women or immunocompromised adults with malignancy, diabetes mellitus, or HIV. Also, patients with either asplenia or functional asplenia, such as those with sickle cell disease, may be at risk for invasive GBS infection, given the spleen’s important role in neutralizing encapsulated organisms.

Epidemiology

Colonization and infection in neonates largely correlate with maternal colonization at the time of delivery. Vertical transmission from colonized mothers to their neonates occurs in approximately 41% to 72% of cases (mean, approximately 50%). However, about 1% to 12% of colonized infants (mean, 5%) are born to non-colonized mothers.[8] Furthermore, heavy maternal colonization in the genital tract (greater than 10 colony-forming units per milliliter) greatly increases the rate of vertical transmission and the rate of heavily colonized infants. Heavily colonized infants are then more likely to have either early- or late-onset GBS disease.

Before the widespread use of intrapartum prophylactic antibiotics, reported attack rates of early-onset neonatal GBS infections ranged from 1.8 to 4.0 per 1000 live births. Early-onset disease (onset within the first six days of life) accounted for approximately 80% of cases or about 7600 cases annually. Following the 2002 guidelines for universal screening of pregnant women at 35 to 37 weeks’ gestation and administration of prophylactic antibiotics to colonized women, the incidence of early-onset disease has decreased to approximately 0.25 cases per 1000 live births, a finding representing a decline of nearly 85% from 1990.[9] See Graph. Incidence of Early and Late-Onset Group B Streptococcus Disease.

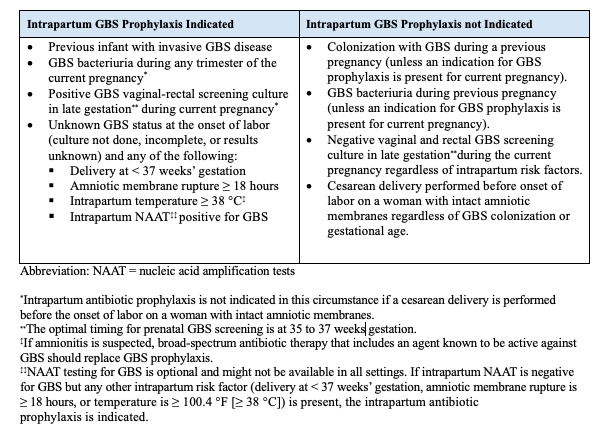

However, the incidence of late-onset disease (onset from 7 through 89 days of life) was not changed through maternal intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis, remaining at approximately 0.27 per 1000 live births.[10] Late, late-onset GBS disease occurs in infants older than three months of age and accounts for 7% to 13% of childhood GBS infections. Affected infants typically were born before 34 weeks' gestation or have an underlying immunodeficiency or concomitant infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). See Table. Indications and Nonindications for Intrapartum Antibiotic Prophylaxis.

In the past two decades, twofold to fourfold increases in the incidence of GBS disease have occurred in nonpregnant adults, mostly those who have underlying medical conditions or are 65 years of age or older. Residents of nursing homes have a markedly higher incidence of invasive group B streptococcal disease than community residents.[11]

Pathophysiology

In pregnant women colonized with S. agalactiae, bacteria can ascend from the genitourinary tract towards the uterus or bladder. In the uterus, the bacteria can affect the fetal membranes causing chorioamnionitis, potentially leading to premature labor, miscarriage, or intrauterine fetal demise if the bacterium invades the neonate. Alternatively, the bacterium may invade the newborn’s respiratory tract by way of amniotic fluid or contact with the maternal colonization during vaginal delivery, causing inflammation of the lung tissue or GBS pneumonia. Occasionally, S. agalactiae can destroy the baby’s alveolar lining with beta-hemolysin and reach the bloodstream causing bacteremia and concomitant neonatal sepsis. Furthermore, bacteria from the bloodstream may cross the blood-brain barrier and migrate to the cerebral spinal fluid (CSF), causing neonatal meningitis. Finally, although less common, the bacteria may also travel via the bloodstream to joints causing septic arthritis.

History and Physical

Neonatal Infection

GBS remains the primary cause of neonatal sepsis since the 1970s. Based on the age of presentation, it divides into early-onset, late-onset, and late-late onset.

Early-onset disease defines as the onset of infection in the first six days of life, but most neonates (61% to 95%) become ill within the first 24 hours (median, 1 hour). Infants typically present with respiratory distress such as apnea or tachypnea, grunting respirations, and cyanosis. Other signs include lethargy, poor feeding, abdominal distention, pallor, jaundice, tachycardia, and hypotension. Fever usually is present in term neonates, but preterm infants often are non-febrile or hypothermic.

Bacteremia is the most common form of early-onset GBS disease, accounting for approximately 80% of cases. Pneumonia and meningitis, although not uncommon, are less likely presentations in early-onset disease, accounting for 15% and 5% to 10%, respectively.

Late-onset disease, defined as GBS infection from day 7 to day 89 of life (median 37 days), has a similar clinical presentation to early-onset disease.[12] Although bloodstream infections remain the most common presentation of the late-onset disease, meningitis occurs in about 30% of cases, as opposed to 5% in early-onset disease.

Late-onset disease may also present with other less common foci of infections such as osteomyelitis, pyogenic arthritis, and cellulitis-adenitis syndrome.[13] The proximal humerus is the most frequently affected site in infants with osteomyelitis, whereas pyogenic arthritis typically affects the hip and/or knee joints. GBS cellulitis-adenitis syndrome is generally unilateral, involving facial or submandibular sites, although the literature describes it in inguinal, scrotal, and prepatellar regions. It presents with swelling of the affected soft tissue area and enlarged adjacent lymph nodes. Aspiration of the affected area of cellulitis often yields GBS, and concomitant bacteremia is very often present.

Late-onset GBS disease, also known as later-onset or very late-onset disease, is defined as GBS infection in infants three months of age or older. Most cases of late, late-onset GBS disease occur in premature infants or those with very low birth weights whose corrected prepatellar age is less than three months. In term infants late, late-onset GBS disease can be associated with HIV infection or immunodeficiency. The clinical manifestations in these older infants are similar to those in patients with typical late-onset infection; bacteremia without a focus and meningitis are the most common clinical features.

Adults

Invasive GBS disease is a substantial cause of morbidity and mortality in adults over 65 years of age, African American, and adults with diabetes.

Underlying medical conditions are present in most adults with invasive disease. Diabetes (41%), heart diseases (36%), and malignancy (17%) account for the majority of infections.

The most common presenting manifestation is fever, chills, and change in mental status. A large number of infections in adults are associated with pregnancy. GBS accounts for 15% of peripartum endometritis cases, 15% of pregnancy-associated bacteremia, and 15% of wound infections after cesarean.

GBS-associated focal infections include pneumonia, endocarditis, skin and soft tissue infections, and osteomyelitis. About 4% of nonpregnant adults surviving the first episode of GBS bacteremia have a second recurrence when followed for a year.

Evaluation

Definitive testing: Culture of the organism from a sterile body site establishes the diagnosis of GBS infection.

Meningitis in early-onset disease is clinically indistinguishable from bacteremia without a focus, and up to 30% of neonates with meningitis have negative blood cultures. Thus, a lumbar puncture is necessary to determine the presence or absence of meningeal involvement, even in a patient with a focal site of GBS infection.

Rapid antigen detection methods are not appropriate substitutes for cultures from blood or other normally sterile body fluid specimens. Repeating antigen tests during therapy is not recommended. A limited study of real-time PCR to detect DNA in the blood of eight neonates with culture-proven GBS sepsis showed corresponding positive results. However, further prospective studies are necessary to evaluate sensitivity and specificity.

Treatment / Management

Empiric Treatment

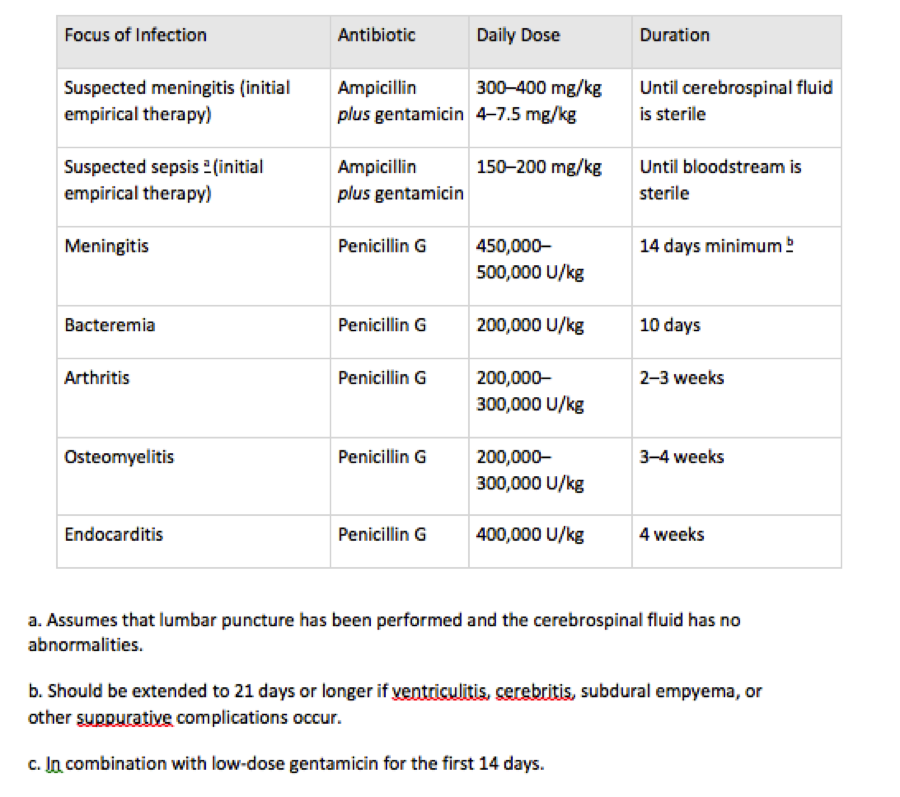

The initial therapy for suspected neonatal sepsis is ampicillin and an aminoglycoside, typically gentamicin. Both ampicillin and gentamicin have activity against GBS, which is the most common cause of neonatal sepsis. Additionally, this combination has a synergistic effect and is more effective than either ampicillin or penicillin G alone in killing most GBS strains in vitro and in vivo. Following confirmation of GBS as the causative pathogen, sterility of the bloodstream and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) are documented, and clinical improvement is observed, penicillin G alone should be used to complete therapy. Recommendations concerning the optimal dose and duration of treatment should be dictated by the focus and severity of the infection.[14]

Specific Treatment

Infants with GBS meningitis should undergo a second lumbar puncture 1-2 days into therapy to document CSF sterility. If CSF culture is negative, treatment therapy can be completed using penicillin G alone for a minimum of 14 days. If CSF culture remains positive, however, a longer treatment course and diagnostic evaluation may be warranted. A contrast-enhanced neuroimaging study can help reveal unresolved cerebritis cases or ventriculitis and can identify the rare infant with complications of subdural empyema or intracranial abscess. Additionally, imaging may identify cerebrovascular complications such as septic thrombophlebitis that can also affect the prognosis. A repeat lumbar puncture should be considered at the completion of therapy to evaluate CSF cell count and protein. Findings of polymorphonuclear cells greater than 30% or protein higher than 200 mg/dL are consistent with cerebritis or parenchymal destruction and may warrant a longer therapy duration. All infants recovering from GBS meningitis should undergo a diagnostic auditory brainstem response (ABR) test.

Infants with bacteremia without focus should receive a total of a 10-day course of IV antibiotics. Relapses, although rare, have been documented if utilizing shorter courses. Oral therapy is not sufficient and has no place in the management of invasive GBS disease. The treatment duration for patients with septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, or endocarditis appears in the table. See Table. Therapeutic Management for Group B Streptococcus Disease in Infants.

Recurrent Infections

The recurrence rate for early-onset GBS disease is approximately 1%. Although rare, recurrence can be due to inadequate dose or duration of therapy, reinfection with a second strain or type, supportive foci, HIV infection, or a humoral immune deficiency. Humoral immune deficiency may be too early to diagnose definitively; however, total IgG levels are usually significantly lower than expected for the patient’s age. Furthermore, susceptibility testing from the first infection and the recurrent episode should be analyzed to ensure in vitro susceptibility to penicillin. If the reason for the recurrence remains unknown, persistent mucous membrane colonization with GBS is the likely source. Beta-lactam antibiotics, even when administered by the parenteral route, do not eradicate GBS colonization reliably. Some studies have shown the benefit of rifampin (20 mg/kg per day) to eradicate mucosal GBS colonization when given orally during the last four days of parenteral therapy. However, a more recent study showed a failure of rifampin to eradicate GBS colonization in infants reliably.[15]

Prevention

Intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP) is indicated for all mothers with a positive GBS screening culture routinely obtained at 35 to 37 weeks’ gestation. Revised guidelines from 2010 also recommend IAP for pregnant women who have a history of GBS bacteriuria at any point during the current pregnancy or have a history of a previous infant with invasive GBS disease. In pregnant women with unknown GBS status, IAP is indicated if any of the following risk factors are present: (1) preterm delivery less than 37 weeks gestation, (2) membrane rupture for 18 hours or greater, (3) an intrapartum temperature of 100.4 F or higher, or (4) intrapartum nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) is positive.

Prophylaxis with a beta-lactam antibiotic (preferably penicillin) given four or more hours before delivery is highly effective for early-onset disease prevention. The initial dose of penicillin G is 5 million units, followed by subsequent doses of 2.5 to 3.0 million units every 4 hours until delivery. Alternatively, patients may instead receive ampicillin, 2 g IV initial dose, then 1 g IV every 4 hours until delivery.

The definition of adequate IAP is administering penicillin, ampicillin, or cefazolin at least 4 hours before delivery.[16] All other medications, doses, or durations are considered inadequate for purposes of neonatal management. Women allergic to penicillin who do not have a history of anaphylaxis, angioedema, respiratory distress, or urticaria after administering penicillin or a cephalosporin should receive cefazolin (2g initially and 1 g every 8 hours until delivery). For women with severe penicillin allergy (anaphylaxis, angioedema, respiratory distress, or urticaria), susceptibility testing should be performed, and clindamycin (900 mg every 8 hours until delivery) or vancomycin (1 g every 12 hours until delivery) can be given to based on susceptibility patterns of the isolated GBS organism. Furthermore, neither clindamycin IAP nor vancomycin IAP has been evaluated for efficacy in preventing early-onset GBS neonatal disease.(B3)

Differential Diagnosis

The signs and symptoms of early-onset GBS disease are clinically indistinguishable from neonatal sepsis caused by other bacterial pathogens, such as:

- Enterobacteriaceae

- Listeria

The prominence of respiratory signs in early-onset disease may lead to confusion with non-infectious causes of respiratory distress, including:

- Respiratory distress syndrome

- Transient tachypnea of the newborn

- Meconium aspiration

The differential diagnosis of late-onset disease depends on the focus of the infection. For example, meningitis in infants of this age may rarely result from Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitidis, Listeria monocytogenes, Haemophilus influenzae (type b and non-typeable), and more commonly with viruses. The findings of osteomyelitis may be subtle; refusal to move the arm may be ascribed to neuromuscular disease or Erb palsy.

Prognosis

The outcome of GBS disease is related to the severity and site of infection. The overall mortality rate remains substantial at 3% to 10% for early-onset disease and 1% to 6% for late-onset disease. Premature infants born before 37 weeks gestation with early-onset disease have the highest mortality rate, approximately 20%.

There is not much information available on the long-term outcome of patients with GBS sepsis without meningitis. In infants with septic shock, the development of periventricular leukomalacia correlated with neurodevelopmental sequelae.

Despite advances in prevention, detection, and care for patients with GBS meningitis, the neurologic outcome of patients remains the same. Approximately 20% to 30% of infants with early- or late-onset meningitis will have permanent severe neurologic impairments such as cortical blindness, bilateral sensorineural hearing loss, cerebral palsy, or severe motor deficits. Another 25% of patients will have mild to moderate impairments such as hydrocephalus requiring a ventriculoperitoneal shunt, seizures, or mild developmental and learning delays. Only 51% of patients demonstrated normal age-appropriate development.

Complications

As previously noted, GBS infection can lead to life-threatening complications in infants, including GBS bacteremia, pneumonia, or meningitis. In pregnant women, common infections due to GBS disease include urinary tract infections, chorioamnionitis, endometritis, or sepsis.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Group B streptococcus (GBS) is a bacterium commonly present in the lower gastrointestinal and genital tracts of up to 35% of healthy women. Although most women colonized with GBS are healthy and have no symptoms, few develop GBS disease when the bacterium invades the body. In pregnant women, this can be critical and life-threatening to both the infant and/or mother. In expecting mothers, GBS disease may cause urinary tract infections, infection of the amniotic fluid surrounding the baby, or infection of the uterus after delivery. GBS infections may even lead to preterm labor or stillbirth.

Pregnant women who carry GBS can also pass on the bacteria to their newborns, and some of those babies may then develop early-onset disease. Although most infants infected with GBS typically present with symptoms immediately after birth, some will develop an infection months following birth. Symptoms include but are not limited to difficulty breathing, grunting sounds, fussiness, sleepiness, poor feeding, low blood pressure, low or high temperatures, or even seizures.

To prevent transmission of GBS from mother to infant, all pregnant women should be screened for GBS colonization as part of their routine prenatal care late in their third trimester (usually between 35 and 37 weeks of gestation). Those who test positive for GBS will receive IV antibiotics during labor to lower the risk of transmission to the baby. Penicillin is the most common and most effective antibiotic given for GBS. However, if a patient is allergic to penicillin, other antibiotics are also available and effective. If the GBS status is unknown at delivery, certain risk factors will determine whether to use antibiotic prophylaxis. Keep in mind; some babies will still get GBS disease even with testing and prophylactic treatment.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Prevention of GBS disease in pregnant women and infants requires an interprofessional healthcare team effort. All healthcare workers caring for pregnant women and newborn infants, including obstetricians, neonatologists, pediatricians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, midwives, and specialty trained nurses, play an important role in screening high-risk patients and treating those with signs or symptoms of GBS-related infection. Furthermore, researchers also play an essential role in investigating the use of vaccines to prevent GBS disease in pregnant women. Pharmacists review antibiotics used for prophylaxis and treatment for doses and interactions. Nurses monitor patients, provide education, and report issues to the team; this includes neonatal specialty nurses for the newborn.

Since the initiation of universal screening and intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis, the incidence of early-onset GBS disease has decreased tremendously by approximately 80%. However, the incidence of late-onset GBS disease remains the same. Thus, further collaboration between all healthcare workers and researchers is essential in understanding the pathophysiology of late-onset GBS disease, the potential use for immunoprophylaxis, and further promoting awareness and education to women regarding GBS disease. These interprofessional team strategies will lead to better outcomes for both mother and child. [Level 5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Burcham LR, Spencer BL, Keeler LR, Runft DL, Patras KA, Neely MN, Doran KS. Determinants of Group B streptococcal virulence potential amongst vaginal clinical isolates from pregnant women. PloS one. 2019:14(12):e0226699. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226699. Epub 2019 Dec 18 [PubMed PMID: 31851721]

Cheng L, Xu FL, Niu M, Li WL, Xia L, Zhang YH, Xing JY. [Pathogens and clinical features of preterm infants with sepsis]. Zhongguo dang dai er ke za zhi = Chinese journal of contemporary pediatrics. 2019 Sep:21(9):881-885 [PubMed PMID: 31506146]

Tevdorashvili G, Tevdorashvili D, Andghuladze M, Tevdorashvili M. Prevention and treatment strategy in pregnant women with group B streptococcal infection. Georgian medical news. 2015 Apr:(241):15-23 [PubMed PMID: 25953932]

Six A,Firon A,Plainvert C,Caplain C,Bouaboud A,Touak G,Dmytruk N,Longo M,Letourneur F,Fouet A,Trieu-Cuot P,Poyart C, Molecular Characterization of Nonhemolytic and Nonpigmented Group B Streptococci Responsible for Human Invasive Infections. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2016 Jan [PubMed PMID: 26491182]

Paoletti LC, Kasper DL. Surface Structures of Group B Streptococcus Important in Human Immunity. Microbiology spectrum. 2019 Mar:7(2):. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.GPP3-0001-2017. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30873933]

Takahashi S, Aoyagi Y, Adderson EE, Okuwaki Y, Bohnsack JF. Capsular sialic acid limits C5a production on type III group B streptococci. Infection and immunity. 1999 Apr:67(4):1866-70 [PubMed PMID: 10085029]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMorinis J, Shah J, Murthy P, Fulford M. Horizontal transmission of group B streptococcus in a neonatal intensive care unit. Paediatrics & child health. 2011 Jun:16(6):e48-50 [PubMed PMID: 22654550]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBerardi A, Rossi C, Creti R, China M, Gherardi G, Venturelli C, Rumpianesi F, Ferrari F. Group B streptococcal colonization in 160 mother-baby pairs: a prospective cohort study. The Journal of pediatrics. 2013 Oct:163(4):1099-104.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.05.064. Epub 2013 Jul 15 [PubMed PMID: 23866714]

Berardi A, Spada C, Vaccina E, Boncompagni A, Bedetti L, Lucaccioni L. Intrapartum beta-lactam antibiotics for preventing group B streptococcal early-onset disease: can we abandon the concept of 'inadequate' intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis? Expert review of anti-infective therapy. 2020 Jan:18(1):37-46. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2020.1697233. Epub 2019 Dec 6 [PubMed PMID: 31762370]

Kristeva M, Tillman C, Goordeen A. Immunization Against Group B Streptococci vs. Intrapartum Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Peripartum Pregnant Women and their Neonates: A Review. Cureus. 2017 Oct 13:9(10):e1775. doi: 10.7759/cureus.1775. Epub 2017 Oct 13 [PubMed PMID: 29946507]

Francois Watkins LK, McGee L, Schrag SJ, Beall B, Jain JH, Pondo T, Farley MM, Harrison LH, Zansky SM, Baumbach J, Lynfield R, Snippes Vagnone P, Miller LA, Schaffner W, Thomas AR, Watt JP, Petit S, Langley GE. Epidemiology of Invasive Group B Streptococcal Infections Among Nonpregnant Adults in the United States, 2008-2016. JAMA internal medicine. 2019 Apr 1:179(4):479-488. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.7269. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30776079]

Nanduri SA, Petit S, Smelser C, Apostol M, Alden NB, Harrison LH, Lynfield R, Vagnone PS, Burzlaff K, Spina NL, Dufort EM, Schaffner W, Thomas AR, Farley MM, Jain JH, Pondo T, McGee L, Beall BW, Schrag SJ. Epidemiology of Invasive Early-Onset and Late-Onset Group B Streptococcal Disease in the United States, 2006 to 2015: Multistate Laboratory and Population-Based Surveillance. JAMA pediatrics. 2019 Mar 1:173(3):224-233. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4826. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30640366]

Ong SW, Barkham T, Kyaw WM, Ho HJ, Chan M. Characterisation of bone and joint infections due to Group B Streptococcus serotype III sequence type 283. European journal of clinical microbiology & infectious diseases : official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology. 2018 Jul:37(7):1313-1317. doi: 10.1007/s10096-018-3252-4. Epub 2018 Apr 18 [PubMed PMID: 29671175]

Procianoy RS, Silveira RC. The challenges of neonatal sepsis management. Jornal de pediatria. 2020 Mar-Apr:96 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):80-86. doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2019.10.004. Epub 2019 Nov 17 [PubMed PMID: 31747556]

Fernandez M, Rench MA, Albanyan EA, Edwards MS, Baker CJ. Failure of rifampin to eradicate group B streptococcal colonization in infants. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2001 Apr:20(4):371-6 [PubMed PMID: 11332660]

. Prevention of Group B Streptococcal Early-Onset Disease in Newborns: ACOG Committee Opinion Summary, Number 782. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2019 Jul:134(1):1. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003335. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31241596]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence