Introduction

Stress injuries represent a spectrum of injuries ranging from periostitis, caused by inflammation of the periosteum, to a complete stress fracture that includes a full cortical break. They are relatively common overuse injuries in athletes that are caused by repetitive submaximal loading on a bone over time. Stress injuries are often seen in running and jumping athletes and are associated with increased volume or intensity of training workload. Most commonly, they are found in the lower extremities and are specific to the sport in which the athlete participates. Upper extremity stress injuries are much less common than lower extremity stress injuries, but when they do occur, they are most commonly seen in the ulna. Similar to the lower extremity injuries, upper extremity stress injuries are the result of overuse and fatigue.

Rib stress fractures are an uncommon site of stress injuries. First rib fractures are the most common, and these are seen in pitchers, basketball players, weightlifters, and ballet dancers. Stress fractures in ribs 4 through 9 are seen in competitive rowers, and posteromedial rib stress fractures can be seen in golfers.

Stress fractures of the pelvis can be vague clinically and mimic other causes of groin and hip pain, for example, adductor strain, osteitis pubis, or sacroiliitis. The most common location is the ischiopubic ramus and sacrum. These injuries are seen most commonly in runners.

Femoral neck stress fractures make up approximately 11% of stress injuries in athletes. The patient complains of hip or groin pain which is worse with weight bearing and range of motion especially internal rotation. There are 2 types of femoral neck stress fractures: tension-type (or distraction) fractures and compression-type fractures. Tension-type femoral neck stress fractures involve the superior-lateral aspect of the neck and are at highest risk for complete fracture; thus, these should be detected early. Compression-type fractures are seen in younger athletes and involve the inferior-medial femoral neck. A trial of non-surgical management can be attempted for patients without a visible fracture line on radiographs in compression type injuries. This injury is common in runners.

Stress fractures of the femoral shaft are well documented in the literature, and in one study among military recruits, they represented 22.5% of all stress fractures. Patients typically complain of poorly localized, insidious leg pain often mistaken for muscle injury. An exam is often nonfocal, although the “fulcrum test” test can be used by providers to localize the affected pain and suggest the diagnosis. If there is no evidence of a cortical break on imaging, a non-surgical approach can be attempted.

The patella is a rare location for a stress fracture and can be oriented either transverse or vertical. Transverse fractures are at higher risk for displacement and immobilization is recommended.

Tibial stress injuries are the most common location of stress reactions and fractures. Medial tibial stress syndrome (MTSS), also known as shin splints or tibial periostitis, can be difficult to distinguish from medial tibial stress fractures. Typically, the patient will be tender over the medial posterior edge of the tibia often made worse with a motor exam. Stress injuries will present with pain during activities of daily living, while MTSS is generally limited to exertional activity. Anterior cortex tibial stress fractures are less common than the posteromedial ones and are found in jumping and leaping athletes. These patients may have the “dreaded black line” on x-ray. They are at a greater risk of nonunion and full cortical break and require aggressive conservative therapy. If that fails, surgical management such as an intramedullary rod or flexible plate is indicated. Stress fractures of the medial tibial plateau are uncommon but can be confused for meniscus injury or pes anserine bursitis, and thus, a high index of suspicion is needed.

Fibular stress fractures are common and most commonly located in the lower third of the fibula, proximal to the tibiofibular ligament. Patients will have reproducible pain on palpation of the affected bone.

Medial malleolus stress fractures are uncommon. Running and jumping athletes can develop vertical stress fractures at the junction of the medial malleolus and tibial plafond. If full cortical disruption is identified, surgical fixation is typically indicated.

Calcaneal stress fractures present as localized tenderness over the heel of the calcaneus posterior to the talus. Patients will have a positive squeeze test.

Stress fractures can develop in the navicular, medial cuneiform, and lateral process of the talus. Navicular stress fractures are difficult to diagnose early on and are at high risk of nonunion due to poor vascular flow, primarily in the middle third. These are common in basketball players and runners. They are usually tender on the navicular bone.

Metatarsal stress fractures account for 9% of all stress fractures in athletes. The second and third metatarsals are most commonly affected and are usually in the neck or distal shaft. They will be point tender with localized swelling over the affected bone. Dancers fracture is a stress fracture at the base of the second metatarsal. Stress fractures distal to the tuberosity of the fifth metatarsal are termed Jones fractures but must be distinguished from an acute Jones fracture.

Sesamoid stress injuries of the great toe present as gradual unilateral plantar pain with the medial (tibial) sesamoid most frequently affected. Direct tenderness or pain with passive extension of the toe aid in diagnosis.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Stress fractures are the partial or complete fracture of a bone as a result of sub-maximal loading. This injury is often compared analogously to fatigue fractures found in engineering materials such as bridges and buildings although some would argue that the mechanisms are different. Normally, submaximal forces do not result in the fracture; however, with repetitive loading and inadequate time for healing and recovery, stress fractures can potentially occur. The debate continues whether the cause is contractile muscle forces acting on a bone or increased fatigue of supporting structures; it is likely that both contribute.[1][2]

Stress fractures can be stratified as high or low risk, a categorization that alludes to the likelihood of propagation to displacement or non-union thus requiring surgical fixation. High-risk areas include the calcaneus, fifth metatarsal, sesamoid, talar neck, tarsal navicular, anterior tibial cortex, medial malleolus, femoral neck, femoral head, patella, and pars interarticularis of the lumbar spine. Low-risk stress injuries include pubic ramus, sacrum, ribs, proximal humerus/humeral shaft, posteromedial tibial shaft, fibula, and second through fourth metatarsal shafts.[3]

Risk factors for stress injuries include energy deficiency through diet (i.e., low caloric intake based on the amount of exercise performed) and hypovitaminosis D. The female athlete triad consisting of disordered eating, amenorrhea or oligomenorrhea, and decreased bone mineral density also increase the risk for stress injuries[4]. Late onset of menarche, metabolic bone disorders including osteomalacia and Paget disease of the bone, and high serum cortisol levels may also be associated with an increased risk. Rapid changes in training programs including increased distance, pace, volume, or cross training without adequate time for adaptation can contribute. Failure to follow intense training days with easy ones for recovery can also contribute to injury.[5]

Because stress injuries frequently occur with a change in training routine, they are common in runners and military recruits. For runners, this may mean an increase in training intensity or a change in footwear or training surface. Increasing distance beyond 32 km (20 miles) per week was found to be associated with an increased rate of stress fractures in one study. In military recruits, these injuries are often associated with the initiation of basic training or changes in training with increased running and marching.

Anatomic and biomechanical risk factors are more difficult to study. Among military recruits, only a narrow width of the tibia and increased external rotation were found to be risk factors for stress fracture. Female runners with stress fractures were found to have smaller calf girth and less lean muscle mass in the lower limb. Previously, ground reaction forces were thought to contribute to the development of lower-limb stress fractures. However, a 2011 systematic review found that the evidence did not support this assumption[6]. On the other hand, the vertical loading rate, or the rate at which the heel strike occurs, was positively associated. On diagnostic imaging, running athletes with stress fractures were found to have smaller tibial cross sectional area than runners without stress fractures. This finding supports the notion that bone geometry plays a role in the development of stress fractures.

Epidemiology

Up to 20% of all sports medicine clinic injuries may be related to stress injuries[7]. They are so common among military recruits that stress injuries are the number one cause of missed training days. Among high school athletes, 0.8% of all injuries sustained were stress fractures[8]. The rate was 1.54 per 100,000 athlete exposures with the incidence highest in cross-country athletes. The lower leg (40.3%) and foot (34.9%) represent the majority of stress injuries. Among elite soccer players, the incidence was 0.04 injuries/1000 hours, and all involved the lower extremity with 78% involving the fifth metatarsal[9]. Among US Army recruits, the rate of stress fractures in men and women was 19.3 with 79.9 cases/1000 recruits.

Stress fractures are more common in weight-bearing than non-weight bearing limbs. Stress fractures of the tibia, metatarsals, and fibula are the most frequently reported sites. Medial tibial stress syndrome, also known as shin splints, is the most common form of early stress injury. This diagnosis reflects a spectrum of medial tibial pain in early manifestations before developing into a stress fracture.

The location of stress injuries varies by sport. Among track athletes, fractures to the navicular, tibia, and metatarsals are most common, and among distance runners, the tibia and fibula are most common. Among dancers, the metatarsals are most afflicted, and in military recruits, the calcaneus and metatarsals are the most commonly fractured site. The ulna is the upper extremity bone most frequently affected.

Pathophysiology

Stress injuries reflect a mismatch between the native bone strength and the chronic mechanical load placed upon the bone. This mismatch can be due to fatigue, i.e., abnormal stress on normal bony architecture, or insufficiency, meaning normal stress on the abnormal bone. Insufficiency stress fracture may be termed pathologic in some literature although the classic definition of pathological fracture refers to a focal bony abnormality.

In healthy bone, osteoblastic activity repairs areas of trauma or injury including that from physical activity. However, if the recovery period is not sufficient for osteoblasts to generate new bone, the rate of resorption by osteoclasts exceeds new bone formation, and thus, the bone weakens. Accumulated repetitively over time, this leads to stress reactions, and if training is not modified, these become completed stress fractures. Advanced imaging studies demonstrate this trabecular bone with linear microfractures from repetitive loading.

Histopathology

The histology of stress fractures show that repetitive stress response leads to increased osteoclastic activity surpassing the rate of osteoblastic activity and new bone formation. Subsequently, there is a weakening of the bone.

History and Physical

Patients will report a history of insidious onset of pain without any specific trauma. They will often describe a history of a significant volume of a specific exercise such as running, an increase in training intensity or volume, or a change in training surface. Initially, symptoms are made worse when training only but may progress to pain with activities of daily living. The symptoms often improve with cessation of activity.

On exam, the clinician will appreciate focal tenderness on the area of a suspected stress injury. There may be soft tissue swelling. Soft tissue tenderness will tend to suggest muscle injury, early stress reaction, or another etiology of the pain whereas bony tenderness is more likely to suggest stress fracture. Some areas of stress injuries may be more clinically subtle or difficult to examine such as the pelvis and sacrum thus requiring the clinician to have a higher index of suspicion from the history alone.

A “one leg hop test” can be used to distinguish between medial tibial stress syndrome and tibial stress fractures. Patients with stress injuries can tolerate repeated jumping whereas stress fractures cannot hop without pain. Of note, the landing is typically when the patient notices the pain.

A 3-point “fulcrum test” can be used to aid in the diagnosis of a femoral shaft stress fracture. The examiner's arm is used as a fulcrum under the thigh while pressure is applied to the knee. A positive test is pain or apprehension at the point of the fulcrum.

Evaluation

Workup of a suspected stress injury initially involves radiographic evaluation of the affected area. X-ray of the affected area will typically appear normal, especially during the first few weeks after onset of symptoms and thus has low sensitivity. Abnormal findings include periosteal elevation, sclerosis, cortical thickening, and potentially a fracture line. Loss of cortical density may also suggest an early-stage stress injury. One may see the so-called “dreaded black line” seen on a tibial or femoral stress fracture or other high-risk stress fractures. Since stress reactions and fractures may not be evident on initial plain radiographs, repeat x-rays, CT, MRI or bone scintigraphy may be indicated.[10][11]

Computerized tomography (CT) findings are similar to plain radiographs with sclerosis, new bone formation, periosteal reaction and fracture lines in long bones. It is helpful to rule out other etiologies if the diagnosis is uncertain based on other imaging.

Bone scintigraphy is moderately sensitive at 74%. Positive findings on scintigraphy will identify high radioisotope activity, or uptake is found in the affected area within a few days of symptom onset. Increased uptake can also be due to other pathology (avascular necrosis, osteomyelitis, neoplasm, among others) which makes specificity low.

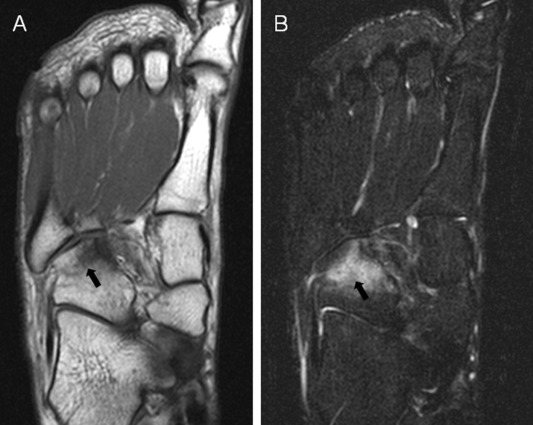

MRI is the most sensitive imaging modality (approximately 88%) and is replacing bone scintigraphy as standard practice for workup of suspected stress injuries[12]. The fracture line usually extends through the cortex into the medullary canal with surrounding bone edema. MRI can also be used to evaluate other possible soft tissue injuries including muscle, ligament, and cartilage injuries.

Treatment / Management

Treatment of stress injuries varies depending on whether it is a stress reaction or stress fracture, by the site of injury, and by its suitability for rehabilitation. Clinicians should recognize which fractures are at risk for delayed union, nonunion, displacement, or intra-articular involvement. It is important to recognize the injury early as early intervention is associated with more rapid healing and recovery. High-risk stress fractures may be managed conservatively or surgically depending on the occupation and sport of choice of the individual.

Stress injuries that are low-risk sites are typically managed conservatively with a 2-phase protocol. Phase one includes analgesia, modified weight bearing, and activity modification including discontinuing the offending activities. If the patient cannot ambulate without pain, temporary immobilization is indicated. Examples of activity modification include water fitness, cycling, and elliptical to maintain strength and fitness. Phase 2 begins after a period of pain-free rest and involves a gradual return to activity over the subsequent weeks including continued physical therapy. For example, a runner may initially start running at half pace and distance every other day. Over the subsequent weeks, one can gradually increase their distance, frequency, and intensity with the goal of returning to their baseline. The length of each phase can vary. A good rule of thumb is however long an injury takes to become pain-free, the same amount of additional time is needed to perform a graduated return to activity. When adding in the time required for rehabilitation training to achieve prior physical fitness levels, loss of training time can be as great as 19 weeks.

Athletes with overly pronated or supinated feet may benefit from orthotics. Inadequate shock absorption may also be ameliorated by changing or addressing footwear. Running shoes should be changed every 300 to 350 miles of use depending on the type of shoe, surface, and athlete[13]. Characteristics of a proper running shoe include heel width and support, firm midsole, and a straight last. Clinicians with expertise in running may be able to perform gait analyses and recommend form changes that will reduce their risk of re-injury.

Females runners with late menarche, fewer menses, and lower bone mineral density are at an increased risk of stress fracture. If history reveals these risk factors, a bone mineral density test and endocrine workup should be considered. Routine supplementation of vitamin D and calcium is not typically indicated unless dietary inadequacy exists. In athletes with repeated stress fractures, testing vitamin D and calcium levels and subsequent supplementation in deficient individuals is recommended. Athletes with eating disorders should be evaluated, and psychiatric testing and nutritional counseling recommended when indicated. Bisphosphonates, which work by inhibiting osteoclastic activity and increasing bone mineral density, have shown early promise in individuals with stress fractures, although more research is required.

Regarding specific types of stress fractures, management varies:

- Rib: Rib stress injuries are managed nonoperatively with rest, analgesia, and cessation of the offending activity. Correction in training errors and faulty mechanics may be helpful as well.

- Pelvis: Pelvic stress injuries are managed conservatively with rest, crutches (if required), and a gradual return to sport.

- Femoral neck: Compression side femoral neck stress injuries can be managed conservatively with non-weight bearing using crutches and activity restriction if the fatigue line is less than 50% of the femoral width. Tension side stress injuries or a compression fracture with fatigue line more than 50% of the femoral neck width typically require open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) with percutaneous screw fixation.

- Femoral shaft: Most femoral shaft stress injuries can be managed conservatively including rest, activity modification, and protected weight bearing. If the patient has low bone mineral density, is older than 60 years old, or has fracture completion or displacement, ORIF with an intramedullary nail is indicated.

- Patella: Patellar stress injuries can be managed conservatively with immobilization and gradual return to activity.

- Tibia: Most tibial shaft stress injuries can be managed conservatively. This includes activity restriction and protected weight-bearing. If the “dreaded black line” is present and violates the anterior cortex, then ORIF with intramedullary tibial nailing or plating may be indicated. This depends on the duration of conservative treatment and the patient’s occupation and the sport in which the patient participates. Medial tibial plateau stress fractures can be managed conservatively. Medial malleolus stress fractures can typically be managed conservatively but should be discussed with one’s orthopedic surgeon.

- Fibula: Fibular stress injuries can be managed conservatively with rest, immobilization, activity modification, and a gradual return to play.

- Tarsals: Calcaneal stress injuries respond well to conservative management with rapid healing and return to activity. Navicular stress injuries are at high risk of nonunion. They can be managed conservatively including non-weight-bearing for up to 12 weeks with close follow up before beginning return to play, or if there’s a completed fracture line, ORIF with screw fixation is typically performed. Medial cuneiform and some talus stress injuries can also be managed conservatively.

- Metatarsals: Most metatarsal fractures can be managed conservatively including adding metatarsal padding as needed. Dancers fractures at the base of the second metatarsal should be made non-weight bearing. Fifth metatarsal stress fractures are at high risk for nonunion and should be non-weight bearing with immobilization and close follow up as they may require surgical intervention. Sesamoid stress fractures require rest from offending activity and immobilization and offloading of the sesamoids.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for stress reaction and a stress fracture is broad and generally specific to the affected area of the patient.

For most patient complaints, the provider must consider other musculoskeletal causes including bursitis, tendonitis, muscle or tendon strain, ligament strain, degenerative changes, arthropathy, radiculopathy, bone contusion, avascular necrosis, neoplasm (osteosarcoma), and infection (osteomyelitis). Where anatomically appropriate, non-musculoskeletal causes could include dermatologic, vascular, neurologic, genitourinary, reproductive, or gastrointestinal etiologies. For example, a stress injury of the pelvis and proximal femur could present as the pelvis, hip, thigh, or groin pain, and the differential should be focused on this region. Stress fractures of the fibula will present as leg pain, and the provider will need to consider the appropriate anatomy.

The differential diagnosis of tibial stress injuries includes periostitis or completed stress fracture, chronic exertional compartment syndrome (CECS), and popliteal artery entrapment syndrome.

Staging

Staging of stress injuries is based on MRI findings which are the most sensitive diagnostic modality. The MRI findings use the Fredericson classification system:

- Grade 1: Periosteal edema only

- Grade 2: Bone marrow edema (only on T2 weighted sequences)

- Grade 3: Bone marrow edema (on T1 and T2 weighted sequences)

- Grade 4: (4a) Multiple discrete areas of intracortical signal changes; (4b) Linear areas of intracortical signal change correlating with a frank stress fracture

One may also visualize a periosteal reaction on x-ray which typically correlates with a grade 3 stress injury on MRI or completed fracture line that correlates with a grade 4 stress injury.

Prognosis

Most athletes will return to play with minimal pain and normal function if provided appropriate relative rest and rehabilitation. If athletes return to play too soon or are inadequately rehabilitated, their pain may lead to chronic injury. Adequate rest, immobilization and non-weight bearing when appropriate, and a gradual return to activity typically result in a return to pre-injury level of play. The primary issue with stress injuries is missed playing time.

Complications

Acute complications from stress injuries include pain, swelling, and missed playing time. Individuals with full cortical break may require surgery and all the risks associated with surgical intervention. Chronic complications include chronic pain, inability to return to the initial level of play, and repeat or recurrent stress fractures.

Consultations

Uncomplicated low-risk stress injuries can be managed without consultation of an orthopedic surgeon or sports medicine physician as long as the managing physician is practicing within his or her expertise and comfortable with diagnosis and management. Low-risk stress injuries include pubic ramus, sacrum, ribs, proximal humerus/humeral shaft, posteromedial tibial shaft, fibula, and second through fourth metatarsal shafts.

High-risk stress fractures should be managed in consultation with an orthopedic surgeon or sports medicine physician. High-risk areas include the calcaneus, fifth metatarsal, second through the fourth metatarsal neck, sesamoid, talar neck, tarsal navicular, anterior tibial cortex, medial malleolus, femoral neck, femoral head, patella, and pars interarticularis of the lumbar spine.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Nearly all stress injuries are a result of overuse or overtraining with inadequate time for recovery. Thus, deterrence of stress injuries is centered around appropriate biomechanics, footwear, training surface, and gradually increasing training intensity. Cross training decreases the likelihood of stress injuries. Maintaining a healthy diet and adequate recovery time are also important for prevention.

Pearls and Other Issues

- Stress injuries are common injuries related to overtraining with inadequate recovery time.

- Most stress injuries will improve with rest, analgesia, activity modification, cross-training, and a gradual return to sport.

- Many low-risk stress injuries can be managed non-operatively with a gradual return to play.

- Certain high risk stress injuries require surgical intervention. Some stress injuries may require surgical intervention if conservative measures fail.

- Refractory or recurrent stress injuries may require endocrinology, metabolic, nutrition or psychiatric workup when appropriate.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Stress injuries are best managed by an interprofessional team that includes therapists and orthopedic nurses. In summary, most stress injuries occur in the lower leg with a female predominance of sustaining a stress injury. Most stress injuries occur in athletes participating in track and field, cross country, tennis, gymnastics, and basketball. Pain with an activity that improves with rest is the most common presentation of a stress injury. Stress injuries are diagnosed by clinical exams in addition to imaging studies including X-ray and at times an MRI. Most stress injuries are treated with rest and a gradual return to play although certain types can require surgical intervention.

The outcomes in most patients are good.[14] (Level V)

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Video to Play)

References

Abe K, Hashiguchi H, Sonoki K, Iwashita S, Takai S. Tarsal Navicular Stress Fracture in a Young Athlete: A Case Report. Journal of Nippon Medical School = Nippon Ika Daigaku zasshi. 2019:86(2):122-125. doi: 10.1272/jnms.JNMS.2019_86-208. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31130563]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceStein CJ, Sugimoto D, Slick NR, Lanois CJ, Dahlberg BW, Zwicker RL, Micheli LJ. Hallux sesamoid fractures in young athletes. The Physician and sportsmedicine. 2019 Nov:47(4):441-447. doi: 10.1080/00913847.2019.1622246. Epub 2019 Jun 5 [PubMed PMID: 31109214]

Bärtschi N, Scheibler A, Schweizer A. Symptomatic epiphyseal sprains and stress fractures of the finger phalanges in adolescent sport climbers. Hand surgery & rehabilitation. 2019 Sep:38(4):251-256. doi: 10.1016/j.hansur.2019.05.003. Epub 2019 May 16 [PubMed PMID: 31103479]

Fredericson M, Kent K. Normalization of bone density in a previously amenorrheic runner with osteoporosis. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2005 Sep:37(9):1481-6 [PubMed PMID: 16177598]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSchilcher J, Bernhardsson M, Aspenberg P. Chronic anterior tibial stress fractures in athletes: No crack but intense remodeling. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports. 2019 Oct:29(10):1521-1528. doi: 10.1111/sms.13466. Epub 2019 Jun 2 [PubMed PMID: 31102562]

Zadpoor AA, Nikooyan AA. The relationship between lower-extremity stress fractures and the ground reaction force: a systematic review. Clinical biomechanics (Bristol, Avon). 2011 Jan:26(1):23-8. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2010.08.005. Epub 2010 Sep 16 [PubMed PMID: 20846765]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceYang J, Tibbetts AS, Covassin T, Cheng G, Nayar S, Heiden E. Epidemiology of overuse and acute injuries among competitive collegiate athletes. Journal of athletic training. 2012 Mar-Apr:47(2):198-204 [PubMed PMID: 22488286]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceChangstrom BG, Brou L, Khodaee M, Braund C, Comstock RD. Epidemiology of stress fracture injuries among US high school athletes, 2005-2006 through 2012-2013. The American journal of sports medicine. 2015 Jan:43(1):26-33. doi: 10.1177/0363546514562739. Epub 2014 Dec 5 [PubMed PMID: 25480834]

Ekstrand J, Torstveit MK. Stress fractures in elite male football players. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports. 2012 Jun:22(3):341-6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2010.01171.x. Epub 2010 Aug 30 [PubMed PMID: 20807388]

Kola S, Granville M, Jacobson RE. The Association of Iliac and Sacral Insufficiency Fractures and Implications for Treatment: The Role of Bone Scans in Three Different Cases. Cureus. 2019 Jan 10:11(1):e3861. doi: 10.7759/cureus.3861. Epub 2019 Jan 10 [PubMed PMID: 30899612]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGmachowska AM, Żabicka M, Pacho R, Pacho S, Majek A, Feldman B. Tibial stress injuries - location, severity, and classification in magnetic resonance imaging examination. Polish journal of radiology. 2018:83():e471-e481. doi: 10.5114/pjr.2018.80218. Epub 2018 Nov 5 [PubMed PMID: 30655927]

Fredericson M, Jennings F, Beaulieu C, Matheson GO. Stress fractures in athletes. Topics in magnetic resonance imaging : TMRI. 2006 Oct:17(5):309-25 [PubMed PMID: 17414993]

Cook SD, Brinker MR, Poche M. Running shoes. Their relationship to running injuries. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.). 1990 Jul:10(1):1-8 [PubMed PMID: 2197696]

Nguyen A, Beasley I, Calder J. Stress fractures of the medial malleolus in the professional soccer player demonstrate excellent outcomes when treated with open reduction internal fixation and arthroscopic spur debridement. Knee surgery, sports traumatology, arthroscopy : official journal of the ESSKA. 2019 Sep:27(9):2884-2889. doi: 10.1007/s00167-019-05483-6. Epub 2019 Mar 26 [PubMed PMID: 30915513]