Anatomy, Head and Neck: Eye Superior Rectus Muscle

Anatomy, Head and Neck: Eye Superior Rectus Muscle

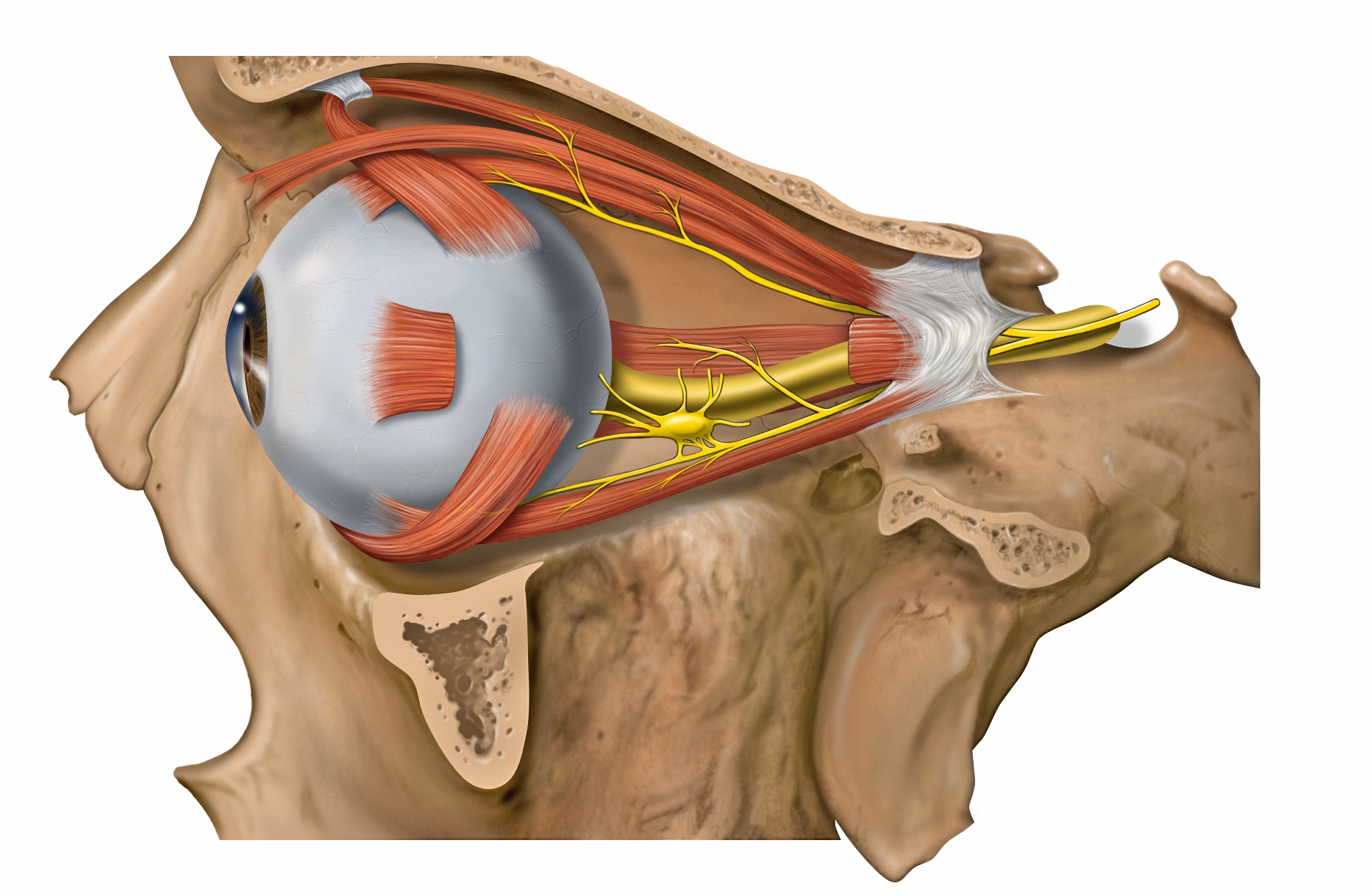

Introduction

The superior rectus is one of the seven extraocular muscles. There are a total of four rectus muscles, two oblique muscles, and the levator palpebrae superioris. The superior rectus is one of the four rectus muscles, which also include the superior rectus, the medial rectus, and the lateral rectus. The oblique muscles are the superior and inferior obliques. The levator palpebrae superioris is primarily responsible for eyelid elevation.[1]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

With the head and eyes facing straight ahead, the eyes are said to be in primary gaze. From this position, an action from an extraocular muscle produces a secondary or tertiary action. Although the globe can be moved about 50 degrees from its primary position, usually during normal eye movement, only 15 degrees of extraocular muscle movement occur before head movement begins.

The annulus of Zinn is the common origin point for the rectus muscles and spans the superior orbital fissure and orbital apex. It consists of superior and inferior tendons. The superior tendon is involved with the entire superior rectus muscle as well as portions of the medial rectus and lateral rectus muscles. The inferior tendon is involved with the inferior rectus muscle and portions of the medial rectus and lateral rectus muscles.

The superior rectus has a primary action of elevating the eye, causing the cornea to move superiorly. The superior rectus originates from the annulus of Zinn and courses anteriorly and superiorly over the globe, making an angle of 23 degrees with the visual axis. This angle causes the secondary and tertiary actions of the superior rectus muscle to be adduction and intorsion (incycloduction).

Each of the extraocular muscles has a functional insertion point, which is at the closest point where the muscle first contacts the globe. This point forms a tangential line from the globe to the muscle origin and is known as the arc of contact. The superior rectus has an arc of contact of 6.5 mm, as does the inferior rectus.[1][2]

Embryology

The mesenchyme of the head, including the orbit and its structures, arises in mesoderm and neural crest cells primarily. The extraocular muscles originate from the mesoderm, but the satellite and connective tissue of the muscle derive from neural crest cells. Most of the remaining connective tissue of the orbit also is derived from neural crest cells.[3]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The superior rectus receives blood primarily from the superior muscular branches of the ophthalmic artery, with some contribution from two anterior ciliary arteries. The primary blood supply for all of the extraocular muscles is the muscular branches of the ophthalmic artery, the lacrimal artery, and the infraorbital artery. The two muscular branches of the ophthalmic artery are the superior and inferior muscular branches.

Venous drainage is similar to the arterial system and empties into the superior and inferior orbital veins. Usually, there are a total of four vortex veins, and these are found at the lateral and medial sides of the superior and inferior rectus muscles. These vortex veins drain into the orbital venous system.[4]

Nerves

The superior rectus is innervated by the superior division of cranial nerve III (oculomotor). Cranial nerve III is divided into upper and lower divisions, with the upper division innervating the superior rectus and levator palpebrae superioris and the lower division to the medial rectus, inferior rectus, and inferior oblique. The lateral rectus is innervated by cranial nerve VI (abducens), and the superior oblique is innervated by cranial nerve IV (trochlear).[5]

Muscles

The superior rectus and the inferior rectus are vertical rectus muscles. The medial and lateral rectus muscles are the horizontal rectus muscles. Each of the rectus muscles originates posteriorly at the annulus of Zinn and courses anteriorly.

Each of the rectus muscles inserts on the globe at varying distances from the limbus, and the curved line drawn along the insertion points makes a spiral that is known as the spiral of Tillaux. Starting at the medial aspect of the globe, the medial rectus inserts at 5.5 mm from the limbus, the inferior rectus inserts at 6.5 mm from the limbus, the lateral rectus inserts at 6.9 mm from the limbus, and the superior rectus at 7.7 mm from the limbus. The medial and lateral recti insert along the horizontal meridian, while the inferior and superior recti insert along the vertical meridian.

The superior rectus is 10.6 mm wide at its insertion on the globe. The tendon is 5.8 mm, measured from the origin. The entire length of the muscle is 41.8 mm.

Extraocular muscles have a large ratio of nerve fibers to skeletal muscle fibers. The ratio is 1:3 to 1:5; other skeletal muscles are 1:50 to 1:125. Extraocular muscles are a specialized form of skeletal muscle with a variety of fiber types, including both slow tonic types, which resist fatigue, and saccadic (rapid) type muscle fibers.[5][6]

Physiologic Variants

The size of the superior rectus muscle, as well as its insertion point on the globe from the limbus and other anatomical measurements, may vary widely from one individual to the next. The numbers described in this article reflect average distances. Congenital differences in extraocular muscles can cause ocular misalignment.

Surgical Considerations

The nerves to the rectus muscles and superior oblique muscles insert into the muscles at one-third the distance from the origin to the insertion. This makes damage to these nerves during anterior segment surgery difficult but not impossible. Instruments that are advanced 26 mm posterior to the rectus muscle insertions can cause injury to the nerve.

Blood vessels may be compromised during surgery of the superior rectus muscle. The vessels which supply blood to the extraocular muscles also supply nearly all the temporal half of the anterior segment of the eye. Most of the nasal half of the anterior segment circulation also derives from blood vessels that supply the extraocular muscles. Therefore, care must be taken during surgery of the superior rectus or other extraocular muscles to avoid disrupting this blood supply.

Other complications may result from superior rectus surgery, which also may result from other rectus muscle surgery. Unsatisfactory alignment is the most common complication and may require additional surgery to correct. Refractive changes may occur when two rectus muscles of one eye are operated on; this may resolve over months. Other possible surgical complications include diplopia, perforation of the sclera, and postoperative infections. Although uncommon, serious infections may result after strabismus surgery, including pre-septal or orbital cellulitis and endophthalmitis.

The superior rectus muscle associates somewhat with the levator palpebrae superioris muscle; therefore, procedures targeted toward the superior rectus may also cause changes in the upper eyelid. When the superior rectus is resected, the palpebral fissure may narrow, and the eyelid may come forward. When the superior rectus muscle is recessed, the palpebral fissure may widen, and the eyelid may be pulled upward. [7][8][9][10][11][12]

Clinical Significance

The function of the superior rectus muscle can be assessed along with the other extraocular muscles during the clinical exam. The movement of the extraocular muscles can be assessed by having the patient look in nine directions starting with a primary gaze, followed by the secondary positions (up, down, left, and right) and the tertiary positions (up and right, up and left, down and right, down and left). The clinician can test these positions by having the patient follow the clinician's finger and trace a wide letter "H" in the air. The superior rectus muscle is isolated by asking the patient to elevate the eye in full abduction.

Ocular alignment can be tested further using several methods, including cover tests, corneal light reflexes, dissimilar image tests, and dissimilar target tests. Since many patients with extraocular muscle abnormalities are young children, the clinician may need to employ various clever means, such as using toys or other objects to elicit the cooperation of the child.

Strabismus, or ocular misalignment, can be caused by abnormalities in binocular vision or abnormalities of neuromuscular control. Weakness, injury, or paralysis that involves the superior rectus muscle can be involved in strabismus.[13][14]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Haładaj R, Wysiadecki G, Polguj M, Topol M. Bilateral muscular slips between superior and inferior rectus muscles: case report with discussion on classification of accessory rectus muscles within the orbit. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2018 Jul:40(7):855-862. doi: 10.1007/s00276-018-1976-6. Epub 2018 Jan 24 [PubMed PMID: 29368252]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWood AJ, Dayal MR. Using a Model to Understand the Symptoms of Ophthalmoplegia. Journal of undergraduate neuroscience education : JUNE : a publication of FUN, Faculty for Undergraduate Neuroscience. 2018 Spring:16(2):R33-R38 [PubMed PMID: 30057507]

Gujar SK, Gandhi D. Congenital malformations of the orbit. Neuroimaging clinics of North America. 2011 Aug:21(3):585-602, viii. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2011.05.004. Epub 2011 Jun 25 [PubMed PMID: 21807313]

Maloveska M, Kresakova L, Vdoviakova K, Petrovova E, Elias M, Panagiotis A, Andrejcakova Z, Supuka P, Purzyc H, Kissova V. Orbital venous pattern in relation to extraorbital venous drainage and superficial lymphatic vessels in rats. Anatomical science international. 2017 Jan:92(1):118-129 [PubMed PMID: 26841898]

Bruenech JR, Kjellevold Haugen IB. How does the structure of extraocular muscles and their nerves affect their function? Eye (London, England). 2015 Feb:29(2):177-83. doi: 10.1038/eye.2014.269. Epub 2014 Nov 14 [PubMed PMID: 25397785]

White MH, Lambert HM, Kincaid MC, Dieckert JP, Lowd DK. The ora serrata and the spiral of Tillaux. Anatomic relationship and clinical correlation. Ophthalmology. 1989 Apr:96(4):508-11 [PubMed PMID: 2726180]

Tibrewal S, Kekunnaya R. Risk of Anterior Segment Ischemia Following Simultaneous Three Rectus Muscle Surgery: Results from a Single Tertiary Care Centre. Strabismus. 2018 Jun:26(2):77-83. doi: 10.1080/09273972.2018.1450429. Epub 2018 Mar 16 [PubMed PMID: 29547011]

Repka MX, Lum F, Burugapalli B. Strabismus, Strabismus Surgery, and Reoperation Rate in the United States: Analysis from the IRIS Registry. Ophthalmology. 2018 Oct:125(10):1646-1653. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.04.024. Epub 2018 May 18 [PubMed PMID: 29779683]

Zloto O, Mezer E, Ospina L, Stankovic B, Wygnanski-Jaffe T. Endophthalmitis Following Strabismus Surgery: IPOSC Global Study. Current eye research. 2017 Dec:42(12):1719-1724. doi: 10.1080/02713683.2017.1351569. Epub 2017 Sep 19 [PubMed PMID: 28925741]

Surachatkumtonekul T, Phamonvaechavan P, Kumpanardsanyakorn S, Wongpitoonpiya N, Nimmannit A. Scleral penetrations and perforations in strabismus surgery: incidence, risk factors and sequelae. Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand = Chotmaihet thangphaet. 2009 Nov:92(11):1463-9 [PubMed PMID: 19938738]

Awad AH, Mullaney PB, Al-Hazmi A, Al-Turkmani S, Wheeler D, Al-Assaf M, Awan M, Zwaan JT, Al-Mesfer S. Recognized globe perforation during strabismus surgery: incidence, risk factors, and sequelae. Journal of AAPOS : the official publication of the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. 2000 Jun:4(3):150-3 [PubMed PMID: 10849390]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePacheco EM, Guyton DL, Repka MX. Changes in eyelid position accompanying vertical rectus muscle surgery and prevention of lower lid retraction with adjustable surgery. Journal of pediatric ophthalmology and strabismus. 1992 Sep-Oct:29(5):265-72 [PubMed PMID: 1432511]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWeinstock VM, Weinstock DJ, Kraft SP. Screening for childhood strabismus by primary care physicians. Canadian family physician Medecin de famille canadien. 1998 Feb:44():337-43 [PubMed PMID: 9512837]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceCampbell LR, Charney E. Factors associated with delay in diagnosis of childhood amblyopia. Pediatrics. 1991 Feb:87(2):178-85 [PubMed PMID: 1987528]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence