Anatomy, Head and Neck, Temporoparietal Fascia

Anatomy, Head and Neck, Temporoparietal Fascia

Introduction

The temporoparietal fascia (TPF) lies under the skin and subcutaneous tissue over the temporal fossa. It is also known as the superficial temporal fascia. It is continuous with the superficial musculoaponeurotic system that is inferior to the zygomatic arch. These two structures are continuous with the platysma muscle in the neck, creating a unified fascia layer from the scalp to the clavicle. The temporoparietal fascia joins the orbicularis oculi and frontalis muscles anteriorly and the occipitalis muscle posteriorly.[1][2][3] It is approximately 2 to 3 mm thick. The layers from the skin to the cranium from superficial to deep in this region are as follows:

- Skin

- Subcutaneous tissue

- Temporoparietal fascia (superficial temporal fascia)

- Innominate fascia

- Deep temporal fascia (divides into a deep and superficial layer)

- Temporalis muscle

- Pericranium

- Cranium

The deep temporal fascia splits into a deep and superficial layer before it inserts into the superior aspect of the zygomatic arch. The superficial temporal fat pad divides these two layers. A proper understanding of the anatomy surrounding the temporoparietal fascia is essential for surgical considerations as it can serve as donor tissue for reconstruction. Additionally, a thorough knowledge of the temporoparietal fascia's relation to surrounding neurovascular structures is integral to safe surgical dissections in this area.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

Beneath the TPF is a loose areolar and avascular plane separating the TPF from the deep temporal fascia. This layer may be referred to as the innominate fascia. It is this plane of tissue that permits the superficial scalp to move freely over the deeper muscular fascial layers. The combination of the superficial loose layers and the deep tight layers allows the scalp to maintain structural integrity with necessary mobility. Additionally, the role of fascia within the human body is to enclose structures (i.e., muscles, viscera, or neurovascular bundles) into discrete organizational patterns.[4]

Embryology

The development of head and neck structures centers on the branchial and pharyngeal apparatus. At 4 to 7 weeks gestation, the head and neck consist of 5 or 6 pairs of branchial arches. The division of branchial arches is by external indentations called branchial clefts, which are lined by ectoderm. The corresponding inward groove is a pharyngeal pouch that is lined by endoderm. The pharyngeal pouch is the primitive pharynx. Branchial arches are composed of mesoderm. Within the branchial arch mesoderm, connective tissue (i.e., cartilage and fascia) will form.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The scalp is rich in arterial anastomoses, with the majority of the blood supply arising from the external carotid artery. The vascular supply to the temporoparietal fascia is the superficial temporal artery, which is the terminal branch of the external carotid artery. It pierces through the substance of the parotid gland anterior to the tragus. The scalp lymphatic system lacks lymph nodes and drains primarily into parotid, anterior/posterior auricular, and occipital lymph nodes. Venous drainage patterns follow that of lymphatic drainage.[5][6]

Nerves

The superficial temporal artery runs within the temporoparietal fascia along with the frontal branch of the facial nerve. The sensory supply to the scalp is from the trigeminal nerve medially and the temporal, auricular, and occipital nerves laterally and posteriorly. Surgical considerations need to account for the course of the frontotemporal branch of the facial nerve in this region. The nerve exits the parotid gland within the parotid-masseteric fascia and will run superiorly within the innominate fascia over the zygomatic arch. At 1.5 to 3 cm above the superior border of the zygomatic arch and 0.9 to 1.4 posterior to the lateral orbital rim, the nerve will transition to a more superficial plane at the undersurface of the TPF. This name for this area is the fascial transition zone.

Muscles

The main muscle occupying the temporal fossa is the temporalis muscle. It is a triangular muscle that broadly originates on the parietal and frontal bone of the temporal fossa and the deep surface of the deep temporal fascia. It attaches to the coronoid process and anterior ramus of the mandible. The trigeminal nerve innervates it via the deep temporal nerves. The action of this muscle is upon the mandible and results in elevation for jaw closure and also causes retraction of the jaw.

Surgical Considerations

The TPF flap provides a wide range of utility in reconstruction within the head and neck. It was first described in 1898 for the reconstruction of an ear (following a horse bite) and reconstruction of the lower eyelid. The advantages provided by the flap are its size and flexibility. Up to 14 cm TPF can be harvested safely, and the flap can act as a fascial, fasciocutaneous, or osseofascial flap. Uses for the TPF are diverse and include forehead/brow, auricular, and lip reconstruction. Additionally, TPF plication can decrease lateral canthal rhytids and elevate the lateral brow during rhytidectomy. Plication also provides deep tissue support and can aid in preventing alopecia and visible scar formation.

When operating in this area, care is necessary to avoid injury to branches of the facial nerve. Dissection in the temporal region is safe above the superficial layer of the deep temporal fascia below the innominate fascia. This approach will ensure that the frontotemporal branch of the facial nerve is superficial to the plane of dissection. Additionally, dissection within the correct plane is necessary for the safe execution of zygomatic arch fracture reduction utilizing the Gilles approach. During this procedure, a 2.5 cm temporal incision is made superior and anterior to the helix within the hairline. Care is necessary to avoid the superficial temporal artery. Dissection continues down to the deep layer of the deep temporal fascia. The fascia is incised, and the temporalis muscle is exposed. An instrument then bluntly dissects between the deep temporalis fascia and the temporalis muscle using a sweeping motion. Once to the level of the depressed zygomatic arch fracture, a Rowe zygomatic elevator is then used to apply an outward force on the fracture.

Additionally, the temporalis fascia has been used routinely in a tympanoplasty for the reconstruction of the tympanic membrane. Given the ease of grafting, this autologous donor site has uses for both medial and lateral tympanoplasty. Temporalis fascia is useful for both subtotal and total repair of tympanic membrane perforations.[7][8][9]

Clinical Significance

As mentioned earlier, a proper understanding of the TPF and its surrounding structures are essential to safely operating in this area. Additionally, understanding fascia layers can help understand the spread of infections and tumors within an anatomical area.

Other Issues

The temporoparietal fascia is a very reliable flap with a good blood supply. However, any injury to the blood supply can easily lead to flap necrosis. In patients with burns, head trauma, or prior surgery to the scalp or skull, the blood supply may suffer compromise - hence its use as a flap is not recommended. One of the ways to assess the blood supply is with the use of Doppler.[10]

Media

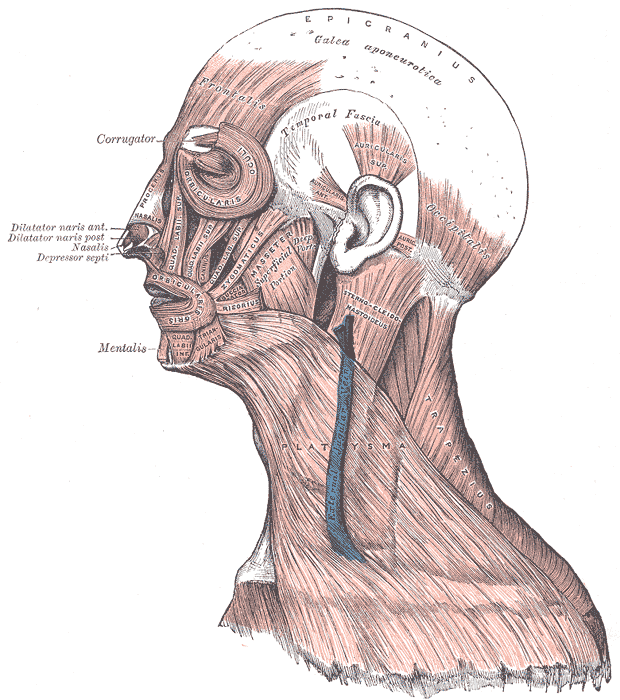

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Muscles of the Head, Face, and Neck. The epicranius, galea aponeurotica, frontalis, temporal fascia, auricularis superior, auricularis anterior, auricularis posterior, occipitalis, sternocleidomastoid, platysma, trapezius, orbicularis oculi, corrugator, procerus, nasalis, dilator naris anterior, dilator naris posterior, depressor septi, mentalis, orbicularis oris, masseter, zygomaticus, and risorius muscles are shown in the image.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

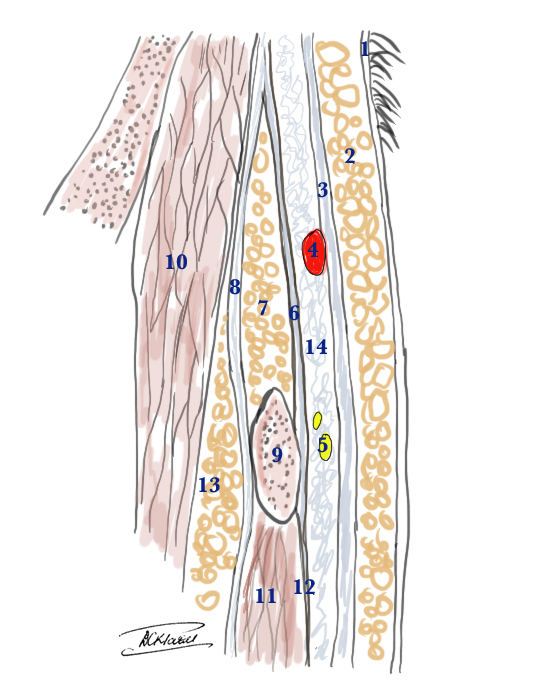

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Superficial Temporal Artery and the Temporal branch of the Facial Nerve: anatomical cross section to show the relative layers above the zygomatic arch 1. Skin 2. Subcutaneous fat 3. Superficial temporal fascia (also called temporoparietal fascia) 4. Temporal artery within the superficial temporal fascia 5. Temporal branch of the facial nerve is just a little deeper than the artery below the superficial temporal fascia 6. Superficial layer of deep temporal fascia 7. Superficial temporal fat pad 8. Deep layer of deep temporal fascia 9. Zygomatic arch 10. Temporalis muscle 11. Masseter muscle 12. Masceteric fascia Contributed by Prof. Bhupendra C. K. Patel MD, FRCS

References

Ferrari M, Vural A, Schreiber A, Mattavelli D, Gualtieri T, Taboni S, Bertazzoni G, Rampinelli V, Tomasoni M, Buffoli B, Doglietto F, Rodella LF, Deganello A, Nicolai P. Side-Door Temporoparietal Fascia Flap: A Novel Strategy for Anterior Skull Base Reconstruction. World neurosurgery. 2019 Jun:126():e360-e370. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.02.056. Epub 2019 Feb 27 [PubMed PMID: 30822581]

Zuo KJ, Wilkes GH. Clinical Outcomes of Osseointegrated Prosthetic Auricular Reconstruction in Patients With a Compromised Ipsilateral Temporoparietal Fascial Flap. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2016 Jan:27(1):44-50. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000002181. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26703031]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMavropoulos JC, Bordeaux JS. The temporoparietal fascia flap: a versatile tool for the dermatologic surgeon. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2014 Sep:40 Suppl 9():S113-9. doi: 10.1097/dss.0000000000000114. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25158871]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLam D, Carlson ER. The temporalis muscle flap and temporoparietal fascial flap. Oral and maxillofacial surgery clinics of North America. 2014 Aug:26(3):359-69. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2014.05.004. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25086696]

Lopez R, Benouaich V, Chaput B, Dubois G, Jalbert F. Description and variability of temporal venous vascularization: clinical relevance in temporoparietal free flap technique. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2013 Nov:35(9):831-6. doi: 10.1007/s00276-013-1087-3. Epub 2013 Feb 26 [PubMed PMID: 23440495]

Demirdover C, Sahin B, Vayvada H, Oztan HY. The versatile use of temporoparietal fascial flap. International journal of medical sciences. 2011:8(5):362-8 [PubMed PMID: 21698054]

Parhiscar A, Har-El G, Turk JB, Abramson DL. Temporoparietal osteofascial flap for head and neck reconstruction. Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery : official journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. 2002 Jun:60(6):619-22 [PubMed PMID: 12022094]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceClymer MA, Burkey BB. Other flaps for head and neck use: temporoparietal fascial free flap, lateral arm free flap, omental free flap. Facial plastic surgery : FPS. 1996 Jan:12(1):81-9 [PubMed PMID: 9244013]

Movassaghi K, Lewis M, Shahzad F, May JW Jr. Optimizing the Aesthetic Result of Parotidectomy with a Facelift Incision and Temporoparietal Fascia Flap. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. Global open. 2019 Feb:7(2):e2067. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000002067. Epub 2019 Feb 8 [PubMed PMID: 30881826]

Jawad BA, Raggio BS. Temporoparietal Fascia Flaps. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32310365]