Introduction

Thoracentesis is a procedure that is performed to remove fluid or air from the thoracic cavity for both diagnostic and/or therapeutic purposes. [1][2] Thoracentesis is also known as thoracocentesis, pleural tap, needle thoracostomy, or needle decompression. A cannula, or hollow needle, is introduced into the thorax after administration of local anesthesia.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

A potential space exists in the left and right side of the chest cavity between the inner chest wall and lung. A trace amount of fluid is found in this space as part of healthy lymphatic drainage, providing lubrication between the lung parenchyma and musculoskeletal structures of the rib-cage during expansion (inhalation) and recoil (exhale).

Excess fluid is pathological. The volume of excessive fluid, the rate of accumulation, the cellular content of the fluid, and the chemical composition of the fluid are all used to guide the management and the differential diagnosis of the underlying etiology.

Thoracentesis is done in either a supine or sitting position depending on patient comfort, underlying condition, and the clinical indication.[3]

Indications

The indications for thoracentesis are relatively broad including diagnostic and therapeutic clinical management. [4]

Thoracentesis should be performed diagnostically whenever the excessive fluid is of unknown etiology. It can be performed therapeutically when the volume of fluid is causing significant clinical symptoms.

Typically, diagnostic thoracentesis is a small volume (single 20cc to 30cc syringe). Unless the etiology is obvious, a first-time thoracentesis should have a diagnostic sample collected for laboratory and pathology analysis.

Typically, therapeutic thoracentesis is a large volume (multiple liters of fluid). A small sample of a large volume thoracentesis should be sent for analysis when the etiology of the fluid is unknown or there is a question of a change in the etiology (e.g., new infection, decompensated chronic condition).

If the volume of fluid is anticipated to reaccumulate quickly, a drain is often left in place to collect this fluid. This often is seen in trauma (e.g., hemothorax), cancer (e.g., malignant effusion), post-operatively (e.g., cardiothoracic post-operative healing/inflammatory conditions), and end-stage metabolic conditions with the systemic excessive colloid leak (e.g., cirrhosis or malabsorption syndromes).

A fluid collection that is believed to be infected should be drained to eliminate the source of infection and/or reservoirs of the infection.

Contraindications

There are no absolute contraindications.

Relative contraindications include any condition that prohibits safe positioning of the patient, uncontrollable coagulation deficits either through medications/iatrogenic or intrinsic, or conditions in which the potential complication of the procedure outway the benefits.

Equipment

Many commercially available prepackaged kits are available. They are convenient but not necessary or required for the safe performance of the procedure.

This is an invasive procedure. The following personal protective equipment and sterile procedure field prep should be used to avoid iatrogenic infection:

- sterile gloves, eye protection, face mask

- sterile drapes or towels

- chlorhexidine or betadine

The safety of the procedure is improved when performed under direct ultrasound guidance. If this is available, a linear probe with a sterile sheath cover should be used.

To enter the thoracic space, the local anesthetic should be applied subcutaneously at the proposed catheter insertion site followed by a tract of anesthetic deep to the skin to the border of the pleural space. Patient comfort will be significantly improved if a generous amount of anesthetic is injected into the intercostal muscle in the area of the proposed insertion. While any need and anesthetic can be used, this is typically accomplished using a 5 or 10cc syringe, and small bore needle (eg 20g works well) and 5-10cc of 0.5-1% lidocaine. Depending on the catheter used for thoracentesis, a single stab incision through the superficial skin of the anesthetized skin will facilitate passage of the catheter. If a commercially available kit is being used, the manufacturer instruction should be reviewed. Selinger technique is used for most kits. The fluid is typically collected by either slow gravity drainage or by hand via serial syringe draws with a collection bag and three-way stop-cock.

Personnel

Historical clues of pathological intrathoracic fluid (eg pleural effusion, hemothorax) include symptoms associated with decreased lung volume (shortness of breath, orthopnea, a sensation of drowning when laying flat), intrathoracic irritation (eg chest pressure/pain, cough, pleuritic pain) and decreased alveolar gas exchange (eg fatigue, light-headedness)

Physical exam clues include diminished or absent breath sounds. This is particularly true if a level of change in auscultation can be appreciated. Egophony, dullness to percussion and tactile fremitus are often appreciated. A very large effusion can cause mass effect and mediastinal shift with tracheal deviation.

Volumes are fluid that may benefit from thoracentesis are typically seen on routine chest radiographs.

Ultrasound is a useful imaging modality to identify the exact level of fluid laying in the chest cavity and identify respiratory variation. Ultrasound can help identify free versus loculated effusions. If using a sterile probe cover, thoracentesis can be facilitated by ultrasound guidance, improving landmark location and site selection. Ultrasound can also be used to monitor resolution of fluid as thoracentesis is performed or post-procedurally. Ultrasound is also more cost-effective and more accessible if performed at the bedside.

CT can provide parenchymal anatomy and mediastinal anatomy that may be beneficial in identifying the underlying etiology. CT is particularly helpful in identifying structures that may be obscured or completely covered by large fluid collections.

Preparation

The patient should have a history and physical examination obtained prior to initiating the procedure. Consent should be obtained. The side and site should be marked in compliance with the invasive procedures policies of the local facility.

Gather all required equipment before starting the procedure. Place the patient on a pulse oximeter. Blood pressure and heart rate should be monitored throughout the procedure.

Technique or Treatment

The preferred site for the procedure is on the affected side in either the midaxillary line if the procedure is being performed in the supine position or the posterior midscapular line if the procedure is being performed in the upright or seated position.

Bedside ultrasound should be used to identify an appropriate location for the procedure. Placing the patient in the upright seated position and using bedside ultrasound can aid in identifying fluid pockets in patients with lower fluid volumes.

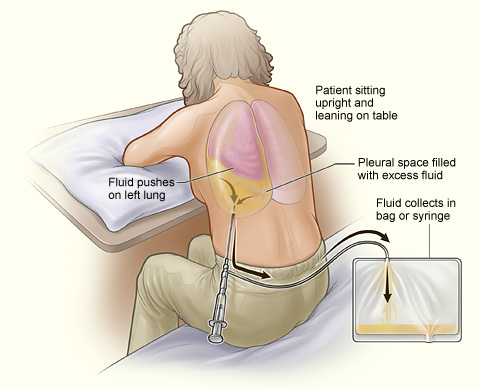

Prep and drape the patient in a sterile fashion. Cleanse the skin with an antiseptic solution. Administer local anesthesia to the skin (25 gauge needle to make a wheal at the surface of the skin) and soft tissue. After the local anesthetic is administered use a larger 20 or 22 gauge needle to infiltrate the tissue around the rib, marching the needle tip just above the rib margin. Insert the needle, or catheter attached to a syringe, or the prepackaged catheter directly perpendicular to the skin. If using a catheter kit, it may be helpful to make a small nick in the skin using an 11-blade scalpel to be able to advance the catheter through the skin and soft tissue smoothly. Apply negative pressure to the syringe during needle or catheter insertion until a loss of resistance is felt and a steady flow of fluid is obtained. This is paramount to detect unwanted entry into a vessel or other structure. Advance the catheter over the needle into the thoracic cavity. After you collect sufficient fluid in the syringe for fluid analysis, either remove the needle (if performing a diagnostic tap) or connect the collecting tubing to either the needle or the catheter's stopcock. Drain larger volumes of fluid into a plastic drainage bag using gravity feed or serial syringe draw with a three-way stop-cock. After you have drained the desired amount of fluid, remove the catheter and hold pressure to stop any bleeding from the insertion site. See Image. Thoracentesis.

Complications

Complications include bleeding, pain, and infection at the point of needle entry. If the approach is made too high in the intercostal space, damage to the coastal vasculature and nerve injury is possible. If too much fluid is removed or if the fluid is removed too rapidly (eg, using negative pressure chambers), re-expansion (aka post-expansion) pulmonary edema may occur. Removal of significant fluid volumes may also induce vasovagal physiology. If the procedural needle/catheter is passed through diseased tissue prior to entering the chest cavity, that process can be extended into the chest space. For example, passing the needle through a thoracic or pleural tumor can seed the thoracic cavity, or passing the needle through a chest wall abscess or otherwise infected tissue can result in empyema.

If the insertion site is too low, splenic and hepatic puncture can occur.

With the exception of localized pain from the actual procedure, pneumothorax is the most common complication and is reported in 12-30% of cases. Pre and post-chest radiographs are appropriate routine practice.

Rare cases of retained intrapleural or intrathoracic catheter fragments have been reported. This is typically only seen when a catheter over trochar technique is used. To aid in repositioning the catheter is advanced back over the trochar resulting in tear and failure of the catheter integrity.

It is essential to document the presence and location of lung sliding before the procedure. (best examined with a greater than 5 MHz vascular probe). The disappearance of lung sliding or B-lines is suggestive of the interval development of a pneumothorax. Indications of chest tube placement to manage the pneumothorax following thoracentesis are 1. large pneumothorax, 2. progressive, 3. symptomatic pneumothorax. The occurrence of pneumothorax in mechanically ventilated patients should be managed with chest tube placement. [5]

Clinical Significance

Thoracentesis may relieve pressure from fluid on the lungs treating symptoms such as pain and shortness of breath. Evaluation of the fluid remove may determine the underlying cause of excess fluid in the pleural space.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Thoracentesis is typically performed by a physician. The pre and post procedure care is usually done by a nurse. Pain management may require the assistance of the pharmacist. The patient is educated with information such as how the procedure will be done, the potential complications, benefits, and post-procedure care. Consent is obtained from the patient or a family member. The patient should also be told how to minimize the risks; i.e., by proper position and remaining still. In the majority of cases, a nurse is present at the bedside to provide assurance and comfort to the patient during the procedure. Adequate anesthesia should be provided. A post-procedure chest x-ray is performed. If there are no complications, the nurse may advise the patient to ambulate. Any change in vital signs or patient condition should warrant immediate investigation for potential procedural complications. Nursing can provide education about dressing changes. The physician and nurse can prompt the patient with regard to followup and when to call a health care provider.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

Nursing can assist in ensuring supplies are available, patient positioning, medication administration, procedural monitoring and post-procedural monitoring and checks

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Thoracentesis. The illustration shows a person receiving thoracentesis, a nonsurgical procedure that drains the excess fluid that collects in the space between the chest and lungs. The person sits upright and leans on a table to allow excess fluid to drain from the pleural space into a bag.

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (PD-US NIH)

References

Lenaeus MJ, Shepard A, White AA. Routine Chest Radiographs after Uncomplicated Thoracentesis. Journal of hospital medicine. 2018 Nov 1:13(11):787-789. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3042. Epub 2018 Aug 29 [PubMed PMID: 30156580]

Leo F, Makowska M. [Thoracentesis - Step by Step]. Deutsche medizinische Wochenschrift (1946). 2018 Aug:143(16):1186-1192. doi: 10.1055/s-0044-102082. Epub 2018 Aug 7 [PubMed PMID: 30086565]

Alzghoul B, Innabi A, Subramany S, Boye B, Chatterjee K, Koppurapu VS, Bartter T, Meena NK. Optimizing the Approach to Patients With Pleural Effusion and Radiologic Findings Suspect for Cancer. Journal of bronchology & interventional pulmonology. 2019 Apr:26(2):114-118. doi: 10.1097/LBR.0000000000000537. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30048417]

Terra RM,Dela Vega AJM, Treatment of malignant pleural effusion. Journal of visualized surgery. 2018 [PubMed PMID: 29963399]

Cantey EP, Walter JM, Corbridge T, Barsuk JH. Complications of thoracentesis: incidence, risk factors, and strategies for prevention. Current opinion in pulmonary medicine. 2016 Jul:22(4):378-85. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000285. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27093476]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence