Introduction

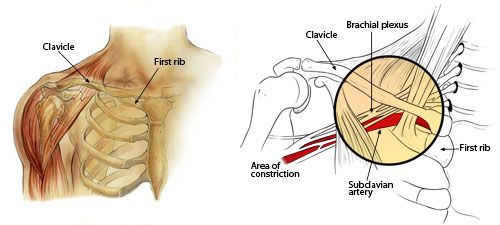

Thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) is a nonspecific diagnosis representing many conditions that involve the compression of the neurovascular structures that pass through the thoracic outlet. TOS was first reported by Rogers in 1949 and more precisely characterized by Rob and Standeven in 1958.[1] Wilbourne suggests five different types of TOS; a venous variant, arterial, a traumatic, a true neurogenic, and a disputed neurogenic.

The first rib, scalene muscles, and the clavicle comprise the thoracic outlet. Patients present with a wide range of symptoms, from minor complaints to debilitating manifestations. Imaging of the musculature and vasculature can help identify this condition. Electrodiagnostic studies can also be useful if the condition is neurologic in origin. Both nonsurgical and surgical treatment methods are options for patients in managing this condition. Patients who are treated appropriately generally fair well, with the vast majority having their symptoms resolve completely.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) manifests when pressures in the thoracic outlet increase to the point of impinging vessels or nerves. These pressures can result from several anatomical abnormalities, such as the thoracic ribs or space-occupying lesions, including tumors or cysts. Fibrous muscular bands from overuse, or in muscular athletes, can cause increased pressures in anatomically normal individuals. Past trauma and neck positioning, a relatively simple explanation, is considered one of the leading causes of TOS symptoms.

Secondary causes can also result in TOS in patients. If a patient has a trapezius muscle deficiency, it can cause the shoulder to depress, which can cause the outlet to diminish, thus increasing the pressure.[2] Another secondary cause could be a fracture of the clavicle, which could also result in depression of the shoulder, causing the same mechanism as explained earlier.

Epidemiology

Several variants of thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) exist, with neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome being the most prevalent by far, accounting for over 90% of all cases. TOS is more prevalent in females and those with poor muscle development, poor posture, or both. Due to the general nature of symptoms, the true prevalence of TOS is hard to determine. Its estimated incidence is anywhere between 3 to 80 cases per 1000 population.[3]

Pathophysiology

The cause of thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS), conceptually, is straightforward. It manifests due to the compression of various structures in the thoracic outlet. Anatomic abnormalities are likely culprits for this increased pressure in the region. Cervical ribs, extra ribs typically arising from the seventh cervical vertebrae, is one of the most common offenders for thoracic outlet syndrome. In a review of 47 neuro TOS operations involving abnormal ribs, 85% of the cases involved cervical ribs. Neck trauma preceded 80% of the total cases of neuro TOS, and this lead investigators to determine the remaining 20% were caused primarily by the anatomic variant. There was also a case reported of bilateral TOS with a patient found to have bilateral cervical ribs inducing physicians to conclude the primary cause was the anatomic abnormality.[4]

Soft tissue components are also major contributors to TOS. Fibrous muscular bands can cause TOS. Tumors or cysts in the thoracic outlet can also increase pressure, thus generate the symptoms seen in TOS.

Thoracic outlet syndrome can present in specific athletes that engage in repetitive motions that involve extreme abduction and external rotation such as competitive swimmers. A classic presentation in a swimmer would be the athlete reporting pain, tightness, or numbness in the neck or shoulder area when their hand enters the water. Other athletes commonly susceptible to this repetitive motion are baseball, water polo, and tennis players.

History and Physical

Patient complaints of thoracic outlet syndrome can be vague and have a wide range of symptoms depending on the etiology of the malady. Nebulous pain is one of the most common complaints amongst all etiologies. Venous obstruction can present with upper extremity swelling, venous distention, and pain ranging from the hand to the forearm.[5] Upper extremity deep venous thromboses (DVTs) can also be present if venous thoracic outlet syndrome persists. The arterial variant of thoracic outlet syndrome can appear with color changes in the upper extremity and diminished pulses.[6] Due to collateral blood flow in the upper extremity, the symptoms can present insidiously and only appear in certain positions in which pressure increases. Neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome, the most common etiology, presents due to compression of the brachial plexus. Similar to the other versions of TOS, vague pain is a common symptom. Atrophy of the intrinsic muscles of the hand can also occur, as well as weakness in the hand and neurologic sensory deficits.

The physical exam, in a patient with suspected TOS, is crucial to confirming the diagnosis and pinpointing the etiology. Improper posture can trigger symptoms, so a quick overview of the patient is necessary. Symmetry and range of motion of both arms should be tested initially. Spurling’s test in which the patient’s head is extended and laterally flexed with the examiner providing axial compression. This test should reproduce radicular pain. In a patient with suspected arterial compression due to TOS, the Adson maneuver should be performed. This test involves extending and slightly abducting the shoulder. The patient extends their neck and turns it toward the examiner’s shoulder while the examiner palpates the radial pulse. The pulse should diminish if arterial compromise is present.[7]

A neurological exam focused on the upper extremity is necessary to evaluate for nerve compression. Gilliatt-Sumner hand is a finding in which the abductor pollicis brevis and the hypothenar muscles become atrophied due to the nerve compression.

The roos stress test can help to test for any variant of TOS. In this test, the patient abducts and externally rotates their shoulders with the elbow at a ninety-degree angle. The patient will then open and close their hand. Fatigue or reproduction of symptoms is a positive result.

Evaluation

The first step in diagnosing thoracic outlet syndrome is the physical exam. After the patient has undergone evaluation, diagnostic confirmation is possible with more advanced imaging or testing. The first step is a basic chest x-ray or cervical spine x-ray.[8] This quick and basic mode of imaging can give the examiner crucial information about the patient’s anatomy, which is likely the culprit of the malady.

Ultrasound has limited importance for TOS due to the inability to see the area of interest in full. However, Longley et al. reported a 92% specificity and 95% sensitivity to diagnose venous TOS.[8]

Angiography can be helpful; however, it remains controversial. Angiography gives highly accurate views of the arterial system of the region, so in theory, it should be ideal for diagnosing arterial TOS. However, arterial TOS is often positional and challenging to reproduce on command, making this an obstacle in this diagnostic approach.[9]

Venous dopplers are useful to help detect compression of the subclavian vein or other veins in the thoracic outlet syndrome. The most significant benefit to this diagnostic modality is the ability to have the patient perform a movement or get into positions to duplicate the increased pressure in the thoracic outlet.

Electrodiagnostic studies (EMS) are a classic diagnostic mode to diagnose neurogenic TOS. Much like the trouble with angiography, EMS has issues with neurogenic TOS often being transient; however, if positive can give a confirmatory diagnosis. A positive result is considered a reduction of less than 85 m/s, and an overall velocity of less than 60 m/s is regarded as an indication for surgery.[7]

Treatment / Management

Thoracic outlet syndrome has two main classifications of treatment; conservative management or surgical intervention. It is common practice, and most physicians recommend, to attempt conservative management initially, except for patients with severe compression causing debilitating symptoms.

Conservative management consists of lifestyle modifications, physical therapy (PT), and rehabilitation. Lifestyle modifications are crucial to treat and prevent future relapses. Postural correction is a common adjustment that can relieve patients’ symptoms. The way the patient sleeps also warrants attention, as they must avoid sleeping in overhead arm positions. If the patient uses repetitive motions at the workplace, preventative splints and pads are an option to provide support to relieve pressure.

Physical therapy is a mainstay as first-line treatment for patients suffering from TOS. For many patients, the cause of the condition is muscular imbalance. Physical therapy aims to strengthen the muscles around the thoracic outlet to relieve pressure on the impaired structures. Published studies have shown positive outcomes for patients who use this therapy to manage and alleviate their symptoms.[10](B3)

In more severe cases of TOS, structural damage, or significant complications can occur, such as upper extremity DVTs or damage to blood vessels from compression.[11] Once these complications receive treatment and resolve, the patient must undergo rehabilitation. Much like physical therapy, it aims at strengthening the muscles of the thoracic outlet, but it also encompasses regaining normal function if such function was lost. Even in patients with severe adverse events, conservative management is still the recommended first-line treatment. (B3)

Surgical intervention is a controversial method of treatment. In patients with a severe compromise of the vasculature of atrophy of intrinsic muscles of the hand, surgery is the recommended approach. However, without credible and substantial evidence that TOS is the culprit, surgery is not recommended. Due to the nonspecific and vague nature of the symptoms, the majority of cases do not have this evidence. Physicians widely recommend against surgical intervention due to the imprecise diagnostic evidence and potential for complications from surgery. A study found the success rate of lower plexus surgical intervention being 75% while upper plexus was 50%. Another study demonstrated patients with nonspecific neurogenic TOS following surgical intervention reported work disability one year after surgery at 60% and 72.5% at 4.8 years.[12](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

Due to the vague nature of the symptoms of thoracic outlet syndrome, many injuries and nondescript pain disorders are common differentials for TOS. One commonly confused disorder is pectoralis minor syndrome. Pectoralis minor syndrome (PMS) presents with pain in the anterior chest wall, trapezius muscle, and over the scapula but also correlates with arm and hand pain or paresthesia. PMS is caused by compression of nerves by the pectoralis minor muscle and not in the thoracic outlet.

Other Differentials Include

- Brachial plexus injuries

- Cervical spine injuries

- Cervical radiculopathy

- Shoulder impingement syndrome

- Elbow or forearm overuse injuries

- Acromioclavicular joint injury

Prognosis

Overall, the prognosis is excellent in patients with thoracic outlet syndrome. Patients who undergo conservative therapy have their symptoms resolve in about 90% of cases. Most of these individuals do not have relapses, as long as their injury was not the result of repetitive movements in which lifestyle modifications would be imperative. Avoidance of activities where their arms remain elevated for extended periods should be limited to produce the best results.

Complications

Due to the benign nature of most treatment modalities and the insidious nature of the condition, TOS does not correlate with high rates of complications. Ischemic change could manifest if a vascular compromise occurs. Venous gangrene and potentially even phlegmasia cerulea dolens can arise in severe cases.

Most of the complications arise from surgical intervention, which is why most physicians recommend conservative therapy. Iatrogenic nerve injury is a feared complication of surgical intervention for TOS. Pneumothorax can result from first rib resection. Bleeding complications are far less common but also are risks of surgical intervention.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) is a family of conditions in which either the blood vessels or nerves are compressed, resulting in nonspecific symptoms such as numbness, tingling, and weakness in the affected area. Imaging can confirm the origin of the condition, but it is not necessary to diagnose TOS. Non-surgical treatment modalities, such as physical therapy, are the first line of treatment, and patients generally respond well. In more severe cases, more invasive treatment methods also are used, such as botox injections and surgical intervention. Once TOS is controlled, and the patient is symptom-free, the patient may need to participate in maintenance physical therapy to prevent any relapse of the condition. In addition to preventive treatment, patients should not perform any repetitive tasks and avoid overhead lifting as much as possible.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Due to the vagueness of thoracic outlet syndrome’s (TOS) symptoms, a patient can present in a wide variety of settings. This fact makes communication between different members of the interprofessional team crucial to expedite diagnosis and to initiate proper treatment. TOS patients can present to the primary care clinician, who could complete the diagnosis but also may be more comfortable with consulting a specialist such as a sports medicine physician or orthopedic surgeon. A study done at Mass General in Boston, Massachusetts, showed e-consults allowed doctors to better prepare for their new patients. As with any condition, proper documentation is essential to make transitions in care smooth and occur without error.

Whether the primary clinician or the orthopedist manages the condition, other members of the healthcare team will make significant contributions. Nursing staff can demonstrate the proper use of braces and splints and answer questions for the patient. They can also monitor progress and inform the clinician of any status changes. If a physical therapist is on the case, they will chart and notify the clinician of progress or lack thereof. In surgical cases, nurses and surgical assistants can be invaluable for assisting the surgeon as well as monitoring and providing postoperative care, with PT and rehabilitation to follow. The interprofessional approach will yield the best patient outcomes in TOS. [Level 5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Park JY, Oh KS, Yoo HY, Lee JG. Case report: Thoracic outlet syndrome in an elite archer in full-draw position. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2013 Sep:471(9):3056-60. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-2865-2. Epub 2013 Feb 22 [PubMed PMID: 23430722]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLevine NA, Rigby BR. Thoracic Outlet Syndrome: Biomechanical and Exercise Considerations. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland). 2018 Jun 19:6(2):. doi: 10.3390/healthcare6020068. Epub 2018 Jun 19 [PubMed PMID: 29921751]

Jones MR, Prabhakar A, Viswanath O, Urits I, Green JB, Kendrick JB, Brunk AJ, Eng MR, Orhurhu V, Cornett EM, Kaye AD. Thoracic Outlet Syndrome: A Comprehensive Review of Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Pain and therapy. 2019 Jun:8(1):5-18. doi: 10.1007/s40122-019-0124-2. Epub 2019 Apr 29 [PubMed PMID: 31037504]

Hussain MA, Aljabri B, Al-Omran M. Vascular Thoracic Outlet Syndrome. Seminars in thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2016 Spring:28(1):151-7. doi: 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2015.10.008. Epub 2015 Oct 28 [PubMed PMID: 27568153]

Stewman C, Vitanzo PC Jr, Harwood MI. Neurologic thoracic outlet syndrome: summarizing a complex history and evolution. Current sports medicine reports. 2014 Mar-Apr:13(2):100-6. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0000000000000038. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24614423]

Grunebach H, Arnold MW, Lum YW. Thoracic outlet syndrome. Vascular medicine (London, England). 2015 Oct:20(5):493-5. doi: 10.1177/1358863X15598391. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26432375]

Povlsen S, Povlsen B. Diagnosing Thoracic Outlet Syndrome: Current Approaches and Future Directions. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland). 2018 Mar 20:8(1):. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics8010021. Epub 2018 Mar 20 [PubMed PMID: 29558408]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKuhn JE, Lebus V GF, Bible JE. Thoracic outlet syndrome. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2015 Apr:23(4):222-32. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-13-00215. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25808686]

Raptis CA, Sridhar S, Thompson RW, Fowler KJ, Bhalla S. Imaging of the Patient with Thoracic Outlet Syndrome. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2016 Jul-Aug:36(4):984-1000. doi: 10.1148/rg.2016150221. Epub 2016 Jun 3 [PubMed PMID: 27257767]

Freischlag J, Orion K. Understanding thoracic outlet syndrome. Scientifica. 2014:2014():248163. doi: 10.1155/2014/248163. Epub 2014 Jul 20 [PubMed PMID: 25140278]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYunce M, Sharma A, Braunstein E, Streiff MB, Lum YW. A case report on 2 unique presentations of upper extremity deep vein thrombosis. Medicine. 2018 Mar:97(11):e9944. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000009944. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29538219]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePeek J, Vos CG, Ünlü Ç, van de Pavoordt HDWM, van den Akker PJ, de Vries JPM. Outcome of Surgical Treatment for Thoracic Outlet Syndrome: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Annals of vascular surgery. 2017 Apr:40():303-326. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2016.07.065. Epub 2016 Sep 22 [PubMed PMID: 27666803]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence