Introduction

In the United States, tonsillectomy is one of the most commonly performed surgical procedures. Over 500,000 cases are performed annually in children less than 15 years of age. Two common reasons for this surgery are sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) and recurrent throat infections. Several complications are documented with tonsillectomy and include, bleeding, velopharyngeal insufficiency, and dehydration. According to the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, the definition of tonsillectomy is a “surgical procedure performed with or without adenoidectomy that completely removes the tonsil, including its capsule, by dissecting the peritonsillar space between the tonsil capsule and the muscular wall. Depending on the context in which it is used, it may indicate tonsillectomy with adenoidectomy, especially in relation to SBD.”[1]

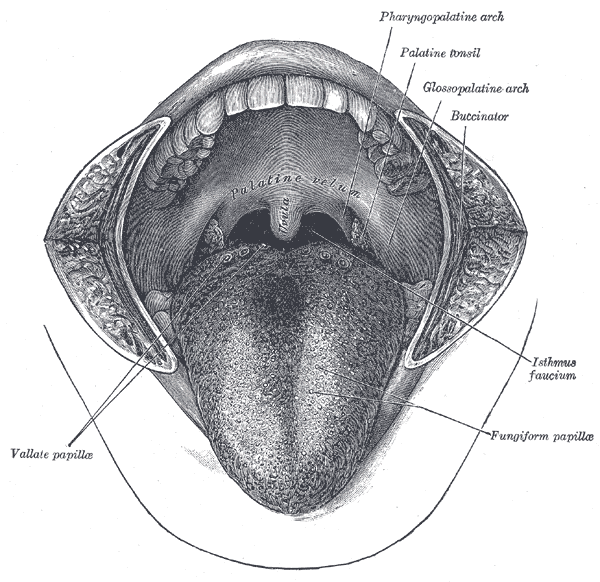

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

The palatine tonsils are a component of Waldeyer’s ring of lymphoid tissue. Other components include the adenoids, tubal tonsils, and the lingual tonsils. The demarcation of the lymphoid tissue from surrounding musculature is by a fibrous capsule that develops from the pharyngobasilar fascia. The potential space between the capsule and muscle is called the peritonsillar space. The tonsils' location is between the palatoglossus and palatopharyngeal muscles which form the anterior and posterior pillars, respectively. The superior constrictor muscle lays lateral to the tonsil. Immediately deep to these muscles is the glossopharyngeal nerve, which is susceptible to injury during tonsillectomy. Transient swelling around this nerve can cause taste alterations and referred otalgia. The tonsils have multiple blood vessels providing its vasculature. The main vessels come from branches of the external carotid artery, and they are: lingual, facial, ascending pharyngeal, and the internal maxillary arteries. The lingual artery gives off the tonsillar branch. The facial artery gives off a tonsillar and ascending palatal branch. The internal maxillary artery supplies tonsil via the descending palatal artery. Numerous anomalies from this architecture can exist.[2][3][4][5]

Indications

As mentioned earlier, the two most common indications for tonsillectomy are sleep-disordered breathing and recurrent tonsillitis. Sleep-disordered breathing is the recurrent partial or complete upper airway obstruction during sleep, resulting in the disruption of normal ventilation and sleep patterns. It can be diagnosed based on history and physical. Symptoms of SBD include hyperactivity, daytime tiredness, and aggression. Signs of SBD include heroic snoring, witnessed apnea, restless sleeping, growth retardation, poor school performance, and nocturnal enuresis. Children with SDB have significantly higher rates of antibiotic use, 40% more hospital visits, and a 215% elevation in healthcare usage from increased upper respiratory infections compared to children without SDB. Tonsillar and adenoid hypertrophies are the most common cause of SDB. Tonsillar size does not always correlate to the severity of SDB and polysomnography can further evaluate patients with signs and symptoms of SDB who are without tonsillar hypertrophy.

Regarding recurrent tonsillitis, it is recommended to use watchful waiting in patients with fewer than seven episodes in the prior year or fewer than five episodes annually in the past 2 years or fewer than three episodes annually in the past 3 years. If the frequency of infections exceeds these numbers, tonsillectomy can be recommended as an option for treatment. Documentation of each infection should include a sore throat and one or more of the following: temperature > 38.3 degrees Celsius, cervical adenopathy, tonsillar exudates, or a positive GABHS. Modifying factors such as antibiotic allergy/intolerance, PFAPA (periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and adenitis) or peritonsillar abscess could warrant earlier surgical intervention in recurrent tonsillitis patients.[1]

Additional indications for tonsillectomy include tonsillar asymmetry (to rule out malignancy) and malignancy. The most common malignancies of the palatine tonsils are squamous cell carcinoma and lymphoma. Most malignant neoplasms in children are lymphoma.[6]

Contraindications

There are no absolute contraindications to tonsillectomy established. The major complications related to tonsillectomy are bleeding and anesthetic risks. Therefore, patients undergoing adenotonsillectomy should have any risk factors for these complications (i.e., bleeding disorders, family history of malignant hyperthermia) identified and addressed preoperatively with necessary precautions.[7]

Equipment

The equipment required for tonsillectomy depends on the technique used. “Cold” tonsillectomy is performed using a Crowe-Davis or McIvor mouth gag, Allis clamp, no. 12 scalpel, curved Metzenbaum scissors, Fisher tonsil knife/dissector, Tyding snares, adenoidectomy curettes, and a St. Clair-Thompson adenoid forceps. “Hot” tonsil dissections are performed using monopolar cautery. Bipolar radiofrequency ablation (i.e., coblation) is also an option. Mircodebrider techniques are also used (especially when performing intracapsular tonsillectomies).

Personnel

Personnel required tonsillectomy includes a surgeon, anesthesiologist, surgical technician, and circulating nurse.

Preparation

Anesthesia is induced similarly regardless of the technique used. The patient is positioned supine and orally intubated. Most surgeons prefer oral RAE endotracheal tubes.[8] The tube is taped at midline. The bed is then turned 45 to 180 degrees to allow the surgeon to sit or stand at the head of the bed and shoulder roll is then placed. A McIvor or Crowe-Davis mouth gag maintains the patient’s mouth in the open position.

Technique or Treatment

Tonsillectomy can be either extracapsular or intracapsular. The “hot” extracapsular technique with monopolar cautery is the most popular technique in the United States. The superior pole of the tonsil is grasped with the Allis clamp, and the tonsil is medialized. The lateral edge of the tonsil is identified submucosally. The superior pole is incised using around 20W of power if a traditional tip is used. The avascular plane between the tonsil and musculature is identified. The entire palatine tonsil is removed typically from the superior to the inferior pole. Maintenance of hemostasis is by packing, suction cautery, or ties.

“Cold” tonsillectomy is performed using sharp dissection. The tonsil is grasped with the Allis clamp and medialized. The lateral aspect of the tonsil is again identified and incised using a number 12 scalpel. A Metzenbaum scissors is then used to identify the avascular plane. Once within the plane, a Fisher tonsil dissector removes the tonsil from the fossa until the tonsil attachment remains only at the inferior pole. A Tyding snare is then used to separate the tonsil from its inferior pole. Maintenance of hemostasis is with pressure from a tonsil sponge, suction cautery or ties.

Coblation can be used to remove the tonsil using a technique similar to monopolar cautery. Coblation utilizes saline irrigation that converts into an ionized plasma layer resulting in a molecular breakdown of tissue. Minimal heat generation takes place, and this is a common technique for partial tonsillectomies. A micro-debrider can be used as well to perform a partial tonsillectomy.[9][10]

Debate remains over the advantages of one technique over the other.[11] Overall, the benefit of one technique depends on the cost, decreased complication rates (i.e., bleeding rates), time in the operating room, and post-operative pain. “Cold” tonsillectomy is thought to result in less post-operative pain, while some studies show “hot” tonsillectomy results in less intraoperative blood loss and surgical time. Choice of technique depends on the surgeon’s experience and comfort level.

Complications

Bleeding is one of the most common and feared complications following tonsillectomy with or without adenoidectomy. A study from 2009 to 2013 involving over one hundred thousand children showed that 2.8% of children had unplanned revisits for bleeding following tonsillectomy, 1.6% percent of patients came through the emergency department, and 0.8% required a procedure.[12] Frequency is higher at night with 50% of bleeding occurring between 10pm-1am and 6am-9am; this is thought to be from changes in circadian rhythm, vibratory effects of snoring on the oropharynx, or drying of the oropharyngeal mucosa from mouth breathing.[13] Risk of bleeding in patients with known coagulopathies may be significantly higher.[14]

Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) is another common complication following tonsillectomy. It occurs in up to 70% of patients who did not receive prophylactic anti-emetics. PONV can lead to increased admission rates, increased need for intravenous hydration, increased need for pain medicine, and decreased patient satisfaction. The recommendation to counter these sequelae is to administer a single dose of intraoperative dexamethasone during tonsillectomy. Some clinicians will routinely prescribe a single dose of ondansetron for outpatient surgeries, as PONV is most likely within the first 24 hours after surgery.

The leading cause of morbidity following tonsillectomy is pain, subsequently leading to diminished oral intake and dehydration, dysphagia, and weight loss. It is important that caregivers are competent to monitor for signs of dehydration and continuously encourage their child to stay hydrated. One method to decrease oropharyngeal pain is alternating scheduled doses or acetaminophen and ibuprofen.[1]

Velopharyngeal insufficiency may also occur following tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy.[15] Symptoms can include hypernasal speech and food regurgitation through the nasal passage during feeding.

Clinical Significance

Tonsillectomy is among the most frequent surgical procedures performed on children in the United States. It is essential for primary care physicians and otolaryngologists to understand the indications, contraindications, and risks associated with this procedure to educate their patients or the patient’s caregiver. It is important for the surgeon to understand the anatomy of the oropharynx to execute a safe surgery and to reduce post-operative complications.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The following guidelines are from the Clinical Practice Guideline: Tonsillectomy in Children from the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery:

"Clinicians should recommend watchful waiting for recurrent throat infection if there have been fewer than 7 episodes in the past year or fewer than 5 episodes per year in the past 2 years or fewer than 3 episodes per year in the past 3 years. [Level II]

Clinicians may recommend tonsillectomy for recurrent throat infection with a frequency of at least 7 episodes in the past year or at least 5 episodes per year for 2 years or at least 3 episodes per year for 3 years with documentation in the medical record for each episode of sore throat and one or more of the following: temperature >38.3°C, cervical adenopathy, tonsillar exudate, or a positive test for GABHS. [Level III]

Clinicians should assess the child with recurrent throat infection who does not meet criteria in Statement 2 for modifying factors that may nonetheless favor tonsillectomy, which may include but are not limited to multiple antibiotic allergy/intolerance, PFAPA (periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and adenitis), or history of peritonsillar abscess. [Level II]

Clinicians should ask caregivers of children with sleep-disordered breathing and tonsil hypertrophy about comorbid conditions that might improve after tonsillectomy, including growth retardation, poor school performance, enuresis, and behavioral problems. [Level II]

Clinicians should counsel caregivers about tonsillectomy as a means to improve health in children with abnormal polysomnography who also have tonsil hypertrophy and sleep-disordered breathing. [Level II]

Clinicians should counsel caregivers and explain that SDB may persist or recur after tonsillectomy and may require further management. [Level II]

Clinicians should administer a single, intraoperative dose of intravenous dexamethasone to children undergoing tonsillectomy. [Level I]

Clinicians should not routinely administer or prescribe perioperative antibiotics to children undergoing tonsillectomy. [Level I]

The clinician should advocate for pain management after tonsillectomy and educate caregivers about the importance of managing and reassessing pain. [Level II]

Clinicians who perform tonsillectomy should determine their rate of primary and secondary post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage at least annually. [Level II] " [1]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Baugh RF, Archer SM, Mitchell RB, Rosenfeld RM, Amin R, Burns JJ, Darrow DH, Giordano T, Litman RS, Li KK, Mannix ME, Schwartz RH, Setzen G, Wald ER, Wall E, Sandberg G, Patel MM, American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Foundation. Clinical practice guideline: tonsillectomy in children. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2011 Jan:144(1 Suppl):S1-30. doi: 10.1177/0194599810389949. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21493257]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceTagliareni JM, Clarkson EI. Tonsillitis, peritonsillar and lateral pharyngeal abscesses. Oral and maxillofacial surgery clinics of North America. 2012 May:24(2):197-204, viii. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2012.01.014. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22503067]

Sholehvar J, Hunsicker RC, Stool SE. Arteriography in posttonsillectomy hemorrhage. Archives of otolaryngology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 1972 Jun:95(6):581-3 [PubMed PMID: 4666430]

Won SY. Anatomical considerations of the superior thyroid artery: its origins, variations, and position relative to the hyoid bone and thyroid cartilage. Anatomy & cell biology. 2016 Jun:49(2):138-42. doi: 10.5115/acb.2016.49.2.138. Epub 2016 Jun 24 [PubMed PMID: 27382516]

Dorrance GM. Ligation of the Great Vessels of the Neck. Annals of surgery. 1934 May:99(5):721-42 [PubMed PMID: 17867182]

Rokkjaer MS, Klug TE. Malignancy in routine tonsillectomy specimens: a systematic literature review. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology : official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS) : affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 2014 Nov:271(11):2851-61. doi: 10.1007/s00405-014-2902-0. Epub 2014 Jan 31 [PubMed PMID: 24481924]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKavanagh KT, Beckford NS. Adenotonsillectomy in children: indications and contraindications. Southern medical journal. 1988 Apr:81(4):507-14 [PubMed PMID: 3162779]

Hatcher IS, Stack CG. Postal survey of the anaesthetic techniques used for paediatric tonsillectomy surgery. Paediatric anaesthesia. 1999:9(4):311-5 [PubMed PMID: 10411766]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChan KH, Friedman NR, Allen GC, Yaremchuk K, Wirtschafter A, Bikhazi N, Bernstein JM, Kelley PE, Lee KC. Randomized, controlled, multisite study of intracapsular tonsillectomy using low-temperature plasma excision. Archives of otolaryngology--head & neck surgery. 2004 Nov:130(11):1303-7 [PubMed PMID: 15545586]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceChang KW. Randomized controlled trial of Coblation versus electrocautery tonsillectomy. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2005 Feb:132(2):273-80 [PubMed PMID: 15692541]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLeinbach RF, Markwell SJ, Colliver JA, Lin SY. Hot versus cold tonsillectomy: a systematic review of the literature. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2003 Oct:129(4):360-4 [PubMed PMID: 14574289]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMahant S, Keren R, Localio R, Luan X, Song L, Shah SS, Tieder JS, Wilson KM, Elden L, Srivastava R, Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings (PRIS) Network. Variation in quality of tonsillectomy perioperative care and revisit rates in children's hospitals. Pediatrics. 2014 Feb:133(2):280-8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1884. Epub 2014 Jan 20 [PubMed PMID: 24446446]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHarounian JA, Schaefer E, Schubart J, Carr MM. Pediatric adenotonsillectomy and postoperative hemorrhage: Demographic and geographic variation in the US. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2016 Aug:87():50-4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2016.05.018. Epub 2016 May 20 [PubMed PMID: 27368442]

Warad D, Hussain FTN, Rao AN, Cofer SA, Rodriguez V. Haemorrhagic complications with adenotonsillectomy in children and young adults with bleeding disorders. Haemophilia : the official journal of the World Federation of Hemophilia. 2015 May:21(3):e151-e155. doi: 10.1111/hae.12577. Epub 2015 Jan 12 [PubMed PMID: 25581525]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDe Buys Roessingh A, El Ezzi O, Richard C, Béguin C, Zbinden-Trichet C, La Scala G, Leuchter I. [Velopharyngeal insufficiency in children]. Revue medicale suisse. 2017 Feb 15:13(550):400-405 [PubMed PMID: 28714631]