Introduction

Previously known as Lyell syndrome, Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) are variants of the same condition and are distinct from erythema multiforme major staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, and other drug eruptions.[1][2][3]

Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis is a rare, acute, serious, and potentially fatal skin reaction in which there are sheet-like skin and mucosal loss accompanied by systemic symptoms. Medications are causative in over 80% of cases.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis is classified by the extent of the detached skin surface area.

- Stevens-Johnson syndrome: less than 10% body surface area

- Overlap Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis: 10% to 30% body surface area

- Toxic epidermal necrolysis more than 30% body surface area

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis is a rare and unpredictable reaction to medication that involves drug-specific CD8+ cytotoxic lymphocytes, the Fas-Fas ligand (FasL) pathway of apoptosis, and granule-mediated exocytosis and tumor necrosis factor-alfa (TNF–alpha)/death receptor pathway. [4][5]

Current theories address the following mechanisms, among others.

- Granulysin, found in the cytotoxic granules, is the main cause of keratinocyte apoptosis.

- Fas–FasL, expressed on the activated cytotoxic T cells, can also destroy keratinocytes via the production of intracellular caspases.

- Cytotoxic T cells exocytose perforin and granzyme B, which create channels in the target cell membrane activating the caspases.

- TNF–alpha may cause apoptosis or protect from it.

- Nitrous oxide (NO) induced by TNF–alpha and interferon (IFN)–alpha may stimulate caspases.

Epidemiology

Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis is estimated to affect two to seven per million people each year. Stevens-Johnson syndrome is three times more common than toxic epidermal necrolysis. Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis can affect anyone with a genetic predisposition: any age, either sex, and all races, although it is more common in older people and women. It is much more likely to occur in people infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), with an estimated incidence of 1/1000.[6][7][8]

- Numerous medications have been reported to trigger Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis.

- Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis are rarely associated with vaccination and infections such as mycoplasma, cytomegalovirus, and dengue.

The drugs that most commonly cause Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis are:

- Anticonvulsants: lamotrigine, carbamazepine, phenytoin, phenobarbitone

- Allopurinol, especially in doses of more than 100 mg per day

- Sulfonamides: cotrimoxazole, sulfasalazine

- Antibiotics: penicillins, cephalosporins, quinolones, minocycline

- Paracetamol/acetaminophen

- Nevirapine (non-nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor)

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (oxicam type mainly)

- Contrast media

Genetic factors include human leukocyte antigen (HLA) allotypes that lead to an increased risk of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis when exposed to aromatic anticonvulsants and allopurinol. Family members of a patient with Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis should be advised that they are at risk of developing the disease and should be cautious about taking any medications associated with the disease.[9]

To date, findings have included the risk of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis in:

- Han Chinese, Thai, Malaysian, and South Indian people if they carry HLA-B*1502 and take aromatic anticonvulsants.

- Han Chinese if they carry HLA-B*5801 and take allopurinol

- Europeans if they carry HLA-B*5701 and take abacavir, or if they carry HLA-A*3101 and take carbamazepine.

Pathophysiology

The initial step for Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis may be interaction/binding of a drug-associated antigen or metabolite with the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) type 1 or cellular peptide to form an immunogenic compound. The exact mechanism is speculative.[10]

Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis is T–cell-mediated.

- CD8+ cells are present in blister fluid and may induce keratinocyte apoptosis.

- Other cells of the innate immune system play a role.

- CD40 ligand cells are also present and may induce the release of TNF–alpha, nitrous oxide, interleukin 8 (IL-8), and cell adhesion antibodies. TNF–alpha also induces apoptosis.

- Both Th1 and Th2 cytokines are present.

Other cells implicated in Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis include macrophages, neutrophils, and natural killer (NK) cells.

The pharmacologic interaction of drugs with the immune system could result in binding of the responsible drug to MHC-1 and the T cell receptor. An alternative theory is a pro-hapten concept, in which drug metabolites become immunogenic and stimulate the immune system.

Histopathology

Histology of the skin reveals necrosis of keratinocytes, epidermal (or epithelial) necrosis, and mild lymphocytic dermal infiltration. Direct immune fluorescence is negative.

Toxicokinetics

The drugs that precipitate Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis tend to have long half-lives and are nearly always taken systemically. Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis can develop within a few days to eight weeks after starting a new drug. A subsequent exposure can result in symptoms within a few hours.

History and Physical

The illness begins with nonspecific symptoms such as fever and malaise, upper respiratory tract symptoms such as a cough, rhinitis, sore eyes, and myalgia. Over the next three to four days, a blistering rash and erosions appear on the face, trunk, limbs, and mucosal surfaces.

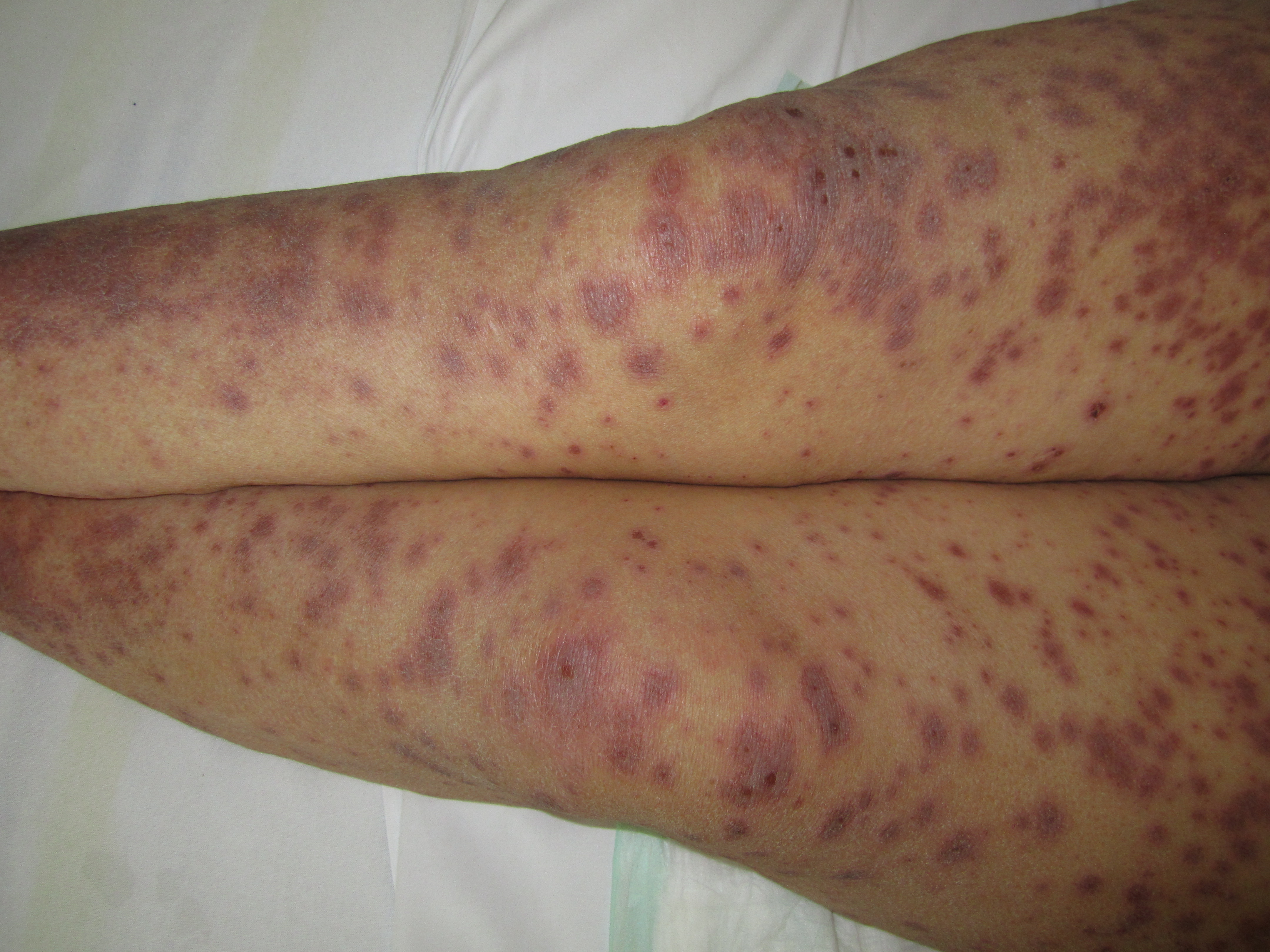

- Erythematous, targetoid, annular, or purpuric macules

- Flaccid bullae

- Large painful erosions

- Nikolsky-positive (lateral pressure on the skin results in shedding of the epidermis)

Early on, toxic epidermal necrolysis displays widespread tender erythroderma and erosions (with or without targetoid rash), whereas Stevens-Johnson syndrome is characterized more by targetoid rash, with fewer areas of denudation.

Mucosal ulceration and erosions can involve lips, mouth, pharynx, esophagus and gastrointestinal tract, eyes, genitals, upper respiratory tract. About half of patients have involvement of three mucosal sites.

The patient is very ill, anxious, and in pain. Liver, kidneys, lungs, bone marrow, and joints may be affected by Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis. Typical symptoms include:

- Fever, malaise, headache, anorexia, pharyngitis

- Symptoms due to acute dysfunction of ocular, pulmonary, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, renal, and hematological systems.

Features may overlap with other severe cutaneous adverse reactions (SCAR), such as acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (causing subcorneal pustules) and drug hypersensitivity syndrome (causing a morbilliform eruption and involving other organs).

Evaluation

Investigations may include:

- Urgent frozen sections of skin biopsy: full-thickness skin necrosis

- Direct immune fluorescence: negative

- Complete blood count (CBC): anemia, lymphopenia, neutropenia, eosinophilia, atypical lymphocytosis

- Liver function tests (LFT): elevated transaminases, hypoalbuminemia

- Renal function: microalbuminuria, renal tubular enzymes in urine, reduced glomerular filtration, rising creatinine and urea, hyponatremia

- Pulmonary function: bronchial mucosal sloughing on bronchoscopy, interstitial infiltrates on chest x-ray

- Cardiac function: abnormal ECG and imaging.

The severity of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis is assessed using SCORTEN. One point is scored for each of the following seven criteria at admission.

- Age older than 40 years

- Presence of a malignancy

- Heart rate of more than 120 bpm

- Initial percentage of epidermal detachment greater than 10%

- Serum urea level greater than 10 mmol/L

- Serum glucose level greater than 14 mmol/L

- Serum bicarbonate level less than 20 mmol/L

The risk of dying from Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis depends on the score. The mortality rate is more than 40 times higher in those with bicarbonate levels less than 20 mmol/L compared with those with higher levels. A SCORTEN ranges with their associated mortality (in %) are as follows: score 0-1 (3.2%), score 2 (12.1%), score 3 (35.3%), score 4 (58.3%), and score 5 (>90%).[11][12]

In patients on multiple drugs known to cause Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis, the algorithm ALDEN has been developed to determine the likely cause.

- The period between drug intake and the onset of reaction (index day): 5 to 28 days (score of 3), 29 to 56 days (2), 1 to 4 days (1), more than 56 days (–1), index day (–3) for the first episode; 1 to 4 days (score of 3), 5 to 56 days (1) for a subsequent episode

- Presence of drug on index day or within five times elimination half-life: stopped (1), unknown (0), stopped earlier (–1), continued beyond index day (–2)

- Previous history of adverse reaction to the same drug: Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (4), Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis to a similar drug (2), other reaction to same or similar drug (1), none (0), previous use without reaction (–2)

- The notoriety of the drug, according to SCAR study: high risk (3), lower risk (2), possible risk (1), under surveillance or new drug (0), no evidence of association (–1)

- Other possible cause: infection (–1), another drug that high risk (–1 for each other drug)

Treatment / Management

Patients should undergo interprofessional assessment in a specialized hospital environment. [13][14][15](B3)

- Intensivist

- Dermatologist

- Plastic surgery or burns specialist

- Ophthalmologist

- Gynecologist

- Urologist

- Respiratory physician

- Physical therapist

- Nutritionist

Care of a patient with Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis requires supportive care [16], including:(B3)

- Cessation of the suspected causative drug(s)

- Hospital admission: preferably to an intensive care and/or burn unit

- Fluid replacement (crystalloid)

- Nutritional assessment: may require nasogastric tube feeding

- Temperature control: warm environment, emergency blanket

- Pain relief

- Supplemental oxygen and, in some cases, intubation with mechanical ventilation

- Sterile/aseptic handling

Skincare requires daily examination of skin and mucosal surfaces for infection, non-adherent dressings, and avoidance of trauma to the skin. Mucosal surfaces require careful cleansing and topical anesthetics.

- Gentle removal of necrotic skin/mucosal tissue

- Culture of skin lesions, axillae, and groins every two days

Antibiotics may be required for secondary infection but are best avoided prophylactically.

It is unknown whether systemic corticosteroids are beneficial, but they are often prescribed in high doses for the first three to five days of admission. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) may be of benefit in patients with severe neutropenia.

Other drugs reported effective include systemic corticosteroids, ciclosporin, TNF-alpha inhibitors [17], N-acetylcysteine, and intravenous immunoglobulins. Their role remains controversial.

Differential Diagnosis

Other acute exfoliative conditions that may need consideration include:

- Other severe cutaneous adverse reactions (SCAR) to drugs, such as drug hypersensitivity syndrome (DHS), acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)

- Other forms of drug eruption

- Erythema multiforme (EM) major

- Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome

- Pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus

- Acute graft versus host disease.[18]

Prognosis

Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis is potentially very serious with high mortality, predicted by the extent and severity at presentation (see SCORTEN and ALDEN above).

Mean adjusted mortality reported for the Nationwide Inpatient Sample 2009-2012 (US) was 4.8% for SJS, 19.4% for SJS/TEN overlap, and 14.8% for TEN.[19]

In Créteil, France, 66 of 361 patients diagnosed with Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis died (18%): 2% with SJS, 12% with SJS/TEN overlap, and 26% with TEN.[20] There has been a trend towards improved mortality in recent years, attributed mainly to better supportive care than in earlier decades.

Complications

In the acute phase, sepsis is the most common serious risk of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis. Organ failure may occur, including pulmonary, hepatic, and renal systems.

The most common long-term complications of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis are ocular (including blindness), cutaneous (pigmentary changes and scarring), and renal. Mucosal involvement with blisters and erosions can lead to strictures and scarring.[21]

Consultations

The care of patients with Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis is multidisciplinary. Patients with blistering involving greater than 10% of the skin surface are usually admitted to intensive care units or burns units for supportive care.

Pearls and Other Issues

Death is mainly due to sepsis and multiorgan failure. Contributing causes are:

- Gastrointestinal bleeding

- Pulmonary embolism

- Myocardial infarction and pulmonary edema

People who have survived Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis must avoid the causative drug or structurally related medicines as Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis may recur. Cross-reactions can occur between:

- Anticonvulsants carbamazepine, phenytoin, lamotrigine and phenobarbital

- Beta-lactam antibiotics penicillin, cephalosporin, and carbapenem

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- Sulfonamides sulfamethoxazole, sulfadiazine, sulfapyridine

Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis survivors may have scarring. Severe consequences can include:

- Ocular sequelae: dry eye, photophobia, pain, symblepharon, corneal scarring or neovascularization, trichiasis, reduced visual acuity, and blindness

- Cutaneous scarring, depigmentation, development of new melanocytic nevi, and pruritus

- Nail dystrophy, onycholysis, and loss of nails (this may recover over time)

- Diffuse scalp hair thinning

- Oral complications: discomfort, dry mouth, periodontal disease, gingival inflammation, synechiae

- Esophageal strictures

- Vulvovaginal stenosis or occlusion in females and phimosis in males

- Persistent pulmonary disease: bronchitis, bronchiectasis, bronchiolitis obliterans, organizing pneumonia, respiratory tract obstruction

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The management of SJS is interprofessional. A number of specialists are usually involved in the care of these patients, including a dermatologist, intensivist, ophthalmologist, pulmonologist, nephrologist, plastic surgeon, and gastroenterologist, functioning as an interprofessional team. The acute care of these patients is provided by wound care. Critical care nurses provide much of the hands-on care. The pharmacist must also closely assess the medications that the patient is receiving to prevent exacerbation of the disorder or determine if any of the patient's medications could be the trigger for the condition. Even after treatment, these patients may have severe cosmetic deficits and may require mental health counseling. If the lesions occur across joints, the patient may benefit from physical therapy to restore function and muscle strength. The patient has to be educated on the use of ocular lubricants because of the sicca-like syndrome. Many patients lose weight after suffering a severe reaction and should be referred to a dietitian. Following discharge, the patients need long-term follow-up to ensure that there are no functional deficits, including vision loss. Once a patient has suffered an SJS, it is highly recommended that the patient wear a warning bracelet indicating the toxic agent or allergen.[22][16] [Level 5]

Outcomes

The outcomes of patients with SJS depend on the extent and severity of skin involvement. For those with a mild eruption, the lesions usually heal in 12 to 16 weeks. Mild scarring may occur, but there is usually no functional loss unless the eyes and other mucous membranes are involved. When the involved skin area is more than 20%, mortality rates of 1 to 27% have been reported. The presence of concomitant bacterial infection can increase mortality rates. Factors that adversely affect the outcome include advanced age, leucopenia, presence of a malignancy, renal dysfunction, hyperglycemia, and more than 10% BSA involvement. Survivors of SJS may develop inverted eyelids, sicca-like syndrome, visual loss, and corneal neovascularization, but an interprofessional approach will lead to better outcomes.[23][24] [Level 5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Jha N, Alexander E, Kanish B, Badyal DK. A Study of Cutaneous Adverse Drug Reactions in a Tertiary Care Center in Punjab. Indian dermatology online journal. 2018 Sep-Oct:9(5):299-303. doi: 10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_81_18. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30258795]

Auyeung J, Lee M. Successful Treatment of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome with Cyclosporine and Corticosteroid. The Canadian journal of hospital pharmacy. 2018 Jul-Aug:71(4):272-275 [PubMed PMID: 30186001]

Iyer G, Srinivasan B, Agarwal S, Ravindran R, Rishi E, Rishi P, Krishnamoorthy S. Boston Type 2 keratoprosthesis- mid term outcomes from a tertiary eye care centre in India. The ocular surface. 2019 Jan:17(1):50-54. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2018.08.003. Epub 2018 Aug 26 [PubMed PMID: 30157458]

Frey N, Bodmer M, Bircher A, Jick SS, Meier CR, Spoendlin J. Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis in Association with Commonly Prescribed Drugs in Outpatient Care Other than Anti-Epileptic Drugs and Antibiotics: A Population-Based Case-Control Study. Drug safety. 2019 Jan:42(1):55-66. doi: 10.1007/s40264-018-0711-x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30112729]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSato S, Kanbe T, Tamaki Z, Furuichi M, Uejima Y, Suganuma E, Takano T, Kawano Y. Clinical features of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Pediatrics international : official journal of the Japan Pediatric Society. 2018 Aug:60(8):697-702. doi: 10.1111/ped.13613. Epub 2018 Jul 30 [PubMed PMID: 29888432]

Yang SC, Hu S, Zhang SZ, Huang JW, Zhang J, Ji C, Cheng B. Corrigendum to "The Epidemiology of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis in China". Journal of immunology research. 2018:2018():4154507. doi: 10.1155/2018/4154507. Epub 2018 Jun 28 [PubMed PMID: 30050956]

Velasco-Tirado V, Alonso-Sardón M, Cosano-Quero A, Romero-Alegría Á, Sánchez-Los Arcos L, López-Bernus A, Pardo-Lledías J, Belhassen-García M. Life-threatening dermatoses: Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis. Impact on the Spanish public health system (2010-2015). PloS one. 2018:13(6):e0198582. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198582. Epub 2018 Jun 18 [PubMed PMID: 29912947]

Safiri S, Ashrafi-Asgarabad A. The risk of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in new users of antiepileptic drugs: Comment on data sparsity. Epilepsia. 2018 May:59(5):1083-1084. doi: 10.1111/epi.14024. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29723404]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWolf R, Marinović B. Drug eruptions in the mature patient. Clinics in dermatology. 2018 Mar-Apr:36(2):249-254. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2017.10.016. Epub 2017 Oct 3 [PubMed PMID: 29566929]

Tangamornsuksan W, Lohitnavy M. Association Between HLA-B*1301 and Dapsone-Induced Cutaneous Adverse Drug Reactions: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA dermatology. 2018 Apr 1:154(4):441-446. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.6484. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29541744]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRichard EB, Hamer D, Musso MW, Short T, O'Neal HR Jr. Variability in Management of Patients With SJS/TEN: A Survey of Burn Unit Directors. Journal of burn care & research : official publication of the American Burn Association. 2018 Jun 13:39(4):585-592. doi: 10.1093/jbcr/irx023. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29901804]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOrtonne N. [Histopathology of cutaneous drug reactions]. Annales de pathologie. 2018 Feb:38(1):7-19. doi: 10.1016/j.annpat.2017.10.015. Epub 2017 Dec 24 [PubMed PMID: 29279184]

Plachouri KM, Vryzaki E, Georgiou S. Cutaneous Adverse Events of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: A Summarized Overview. Current drug safety. 2019:14(1):14-20. doi: 10.2174/1574886313666180730114309. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30058498]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLerma V, Macías M, Toro R, Moscoso A, Alonso Y, Hernández O, de Abajo FJ. Care in patients with epidermal necrolysis in burn units. A nursing perspective. Burns : journal of the International Society for Burn Injuries. 2018 Dec:44(8):1962-1972. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2018.06.010. Epub 2018 Jul 11 [PubMed PMID: 30005991]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKumar R, Das A, Das S. Management of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome-Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis: Looking Beyond Guidelines! Indian journal of dermatology. 2018 Mar-Apr:63(2):117-124. doi: 10.4103/ijd.IJD_583_17. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29692452]

Schneider JA, Cohen PR. Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis: A Concise Review with a Comprehensive Summary of Therapeutic Interventions Emphasizing Supportive Measures. Advances in therapy. 2017 Jun:34(6):1235-1244. doi: 10.1007/s12325-017-0530-y. Epub 2017 Apr 24 [PubMed PMID: 28439852]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceZhang S, Tang S, Li S, Pan Y, Ding Y. Biologic TNF-alpha inhibitors in the treatment of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a systemic review. The Journal of dermatological treatment. 2020 Feb:31(1):66-73. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2019.1577548. Epub 2019 Feb 19 [PubMed PMID: 30702955]

Schwartz RA, McDonough PH, Lee BW. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: Part II. Prognosis, sequelae, diagnosis, differential diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2013 Aug:69(2):187.e1-16; quiz 203-4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.05.002. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23866879]

Hsu DY, Brieva J, Silverberg NB, Silverberg JI. Morbidity and Mortality of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis in United States Adults. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2016 Jul:136(7):1387-1397. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.03.023. Epub 2016 Mar 30 [PubMed PMID: 27039263]

Bettuzzi T, Penso L, de Prost N, Hemery F, Hua C, Colin A, Mekontso-Dessap A, Fardet L, Chosidow O, Wolkenstein P, Sbidian E, Ingen-Housz-Oro S. Trends in mortality rates for Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: experience of a single centre in France between 1997 and 2017. The British journal of dermatology. 2020 Jan:182(1):247-248. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18360. Epub 2019 Sep 11 [PubMed PMID: 31323695]

Lerch M, Mainetti C, Terziroli Beretta-Piccoli B, Harr T. Current Perspectives on Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis. Clinical reviews in allergy & immunology. 2018 Feb:54(1):147-176. doi: 10.1007/s12016-017-8654-z. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29188475]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePapp A, Sikora S, Evans M, Song D, Kirchhof M, Miliszewski M, Dutz J. Treatment of toxic epidermal necrolysis by a multidisciplinary team. A review of literature and treatment results. Burns : journal of the International Society for Burn Injuries. 2018 Jun:44(4):807-815. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2017.10.022. Epub 2018 Apr 4 [PubMed PMID: 29627131]

Antoon JW, Goldman JL, Shah SS, Lee B. A Retrospective Cohort Study of the Management and Outcomes of Children Hospitalized with Stevens-Johnson Syndrome or Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis. The journal of allergy and clinical immunology. In practice. 2019 Jan:7(1):244-250.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2018.05.024. Epub 2018 May 30 [PubMed PMID: 29859332]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAntoon JW, Goldman JL, Lee B, Schwartz A. Incidence, outcomes, and resource use in children with Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Pediatric dermatology. 2018 Mar:35(2):182-187. doi: 10.1111/pde.13383. Epub 2018 Jan 9 [PubMed PMID: 29315761]