Introduction

Primary tracheal tumors are uncommon but usually malignant in adults, accounting for about 0.2 % of all malignant tumors.[1][2] The estimated incidence of tracheal cancers is about 0.1 per 100,000 people per year. The largest report of primary tracheal tumors is based on the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database study of 578 cases.[3] In this analysis, 55% were men, and the major histological type was squamous cell carcinoma, accounting for 45% of the cases. Other histologic types include adenoid cystic carcinoma, small cell carcinoma, large cell carcinoma, sarcoma, adenocarcinoma, and carcinoma not otherwise specified or undifferentiated type. Primary tracheal tumors are almost always malignant in adults (up to 90%), whereas, in children, they are only malignant in about 10 to 30% of the cases.

The presenting symptoms are very non-specific and sometimes result in diagnostic delays. These symptoms include shortness of breath, and wheezing, which could mimic benign entities like asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases, and other reactive airway diseases. Furthermore, not every tumor found in the trachea is a primary tracheal neoplasm. For example, metastatic cancer to paratracheal lymph nodes that invade the trachea may be mistaken for a tracheal primary neoplasm. A thorough radiographic evaluation with histologic correlation can help identify metastatic cancers, which are more common than primary tracheal neoplasms, which are rare.[1] This raises the possibility of primary tracheal tumors being even more uncommon than reported in the general population.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Given the rarity of primary tracheal cancers, etiology has not been established for most of the subtypes, except for squamous cell carcinomas. In this particular type of tracheal cancer, smoking and exposure to other aerosolized carcinogens, including hydrocarbons, have been identified as potential risk factors.[4] Given that approximately 25% of patients with squamous cell cancer of the trachea have a prior history of lung cancer highlights the importance of bronchoscopic surveillance in those patients with a history of squamous cell carcinoma of the lungs after undergoing curative resections or treatments.

Epidemiology

The incidence of tracheal cancers is estimated at 0.1 new cases per 100,000 people per year. It accounts for 0.1% to 0.4% of newly diagnosed cancers annually. Squamous cell carcinoma exhibits male predisposition and occurs between 60 to 70 years of age. Adenoid cystic carcinoma occurs equally in both sexes and is noted predominantly in the fourth and fifth decades.[3][5] Both squamous cell carcinoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma constitute about 66% of all primary tracheal cancers, while the rest one-third of cases are made up of a variety of benign and malignant tumors.

Pathophysiology

Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common trachea cancer and is commonly seen in patients with a smoking history. It constitutes one-third of all primary tracheal tumors. These lesions are primarily found in the lower third of the trachea and involve the posterior wall. Based on a review of 59 cases diagnosed between 1985 and 2008, 24% of tracheal squamous cell cancers were well-differentiated, 49% were moderately differentiated, and 27% demonstrated poor differentiation.[6] The risk of progression or metastasis is associated with poor prognostic markers, including an extension through the tracheal wall, extension to the mediastinum, or metastasis to adjacent lymph nodes.

The next most common type of primary malignant tracheal tumors is adenoid cystic cancers which look similar to salivary gland tumors, which are slow-growing, well-differentiated, and present with infiltration of the submucosal planes resulting in positive margins at surgery due to their longitudinal axis involvement. An analysis of 108 cases of tracheal adenoid cystic carcinoma showed positive microscopic margins (R1) in 55% of cases, and positive macroscopic margins (R2) were noted in 8% of cases.[7]

Adenocarcinoma may be seen in the trachea secondary to the direct invasion from the lung tumor or the involvement of the mediastinal lymph nodes. Patients usually present with obstructive symptoms in the later decades of life and with bulky tumors. Histologically, this tumor would demonstrate large vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli with mucin production.[8]

Histopathology

Tracheal cancer may arise from the epithelial cells, mesenchymal structure, or salivary glands. It is malignant in 90% of cases in adults, while only 10 to 30% of cases are malignant in children.[1][2]

Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common type of primary tracheal carcinoma, followed by adenoid cystic carcinoma. Other types include mucoepidermoid, small cell carcinoma, neuroendocrine carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, large cell carcinoma, sarcomas, fibroma, pleiomorphic adenoma, and other much rarer forms. Squamous cell carcinoma presents with lung and mediastinal metastases in one-third of cases at the time of diagnosis; these lesions may be exophytic or ulcerative. These tumors are characterized by a well-differentiated appearance and keratinization. Several variants were described in 2005 in the WHO classification, including acantholytic carcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma, basaloid variant, papillary carcinoma, spindle-cell carcinoma, and verrucous variant.[9]

In contrast, adenoid cystic carcinomas usually grow slowly over several years.[3][5] Macroscopically, they can show exophytic growth patterns resulting in tracheal stenosis at times. On microscopy, adenoid cystic carcinomas are well-differentiated, and lesions may present as polypoid that may progress to perineural invasion involving the vascular structures.[10] This increases the risk of recurrence after surgical resections. Histologically these tumors are made up of two types of cells: ductal and myoepithelial.[9]

History and Physical

Primary tracheal cancers may present with signs and symptoms of upper airway obstruction (dyspnea, stridor, and wheezing), cough and hemoptysis from mucosal irritation, or symptoms related to invasion of adjacent structures and lead to dysphagia or hoarseness due to recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy. Squamous cell carcinoma usually presents with hemoptysis and is diagnosed within four to six months of symptoms onset, while adenoid cystic carcinoma is slowly growing and presents with dyspnea and wheezing, with a potential for delayed diagnosis.

Several factors play a role in missed and delayed diagnosis. First, non-specific symptoms like a cough, hemoptysis, dyspnea, and wheezing are also present in more common diseases like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, bronchitis, or other infections. Second, the tracheal lumen is usually large with a significant reservoir, and symptoms of obstruction do not occur until the mass occupies more than 50 to 75% of the lumen diameter.[11] Typically a tracheal diameter obstruction of under 0.8 cm results in dyspnea on exertion, whereas an obstruction under 0.65 mm causes dyspnea at rest.[12] Third, adenoid cystic cancer and other benign tumors grow slowly, and symptoms progress slowly over a period of months to years.

A high index of suspicion for tracheal cancer should be raised when respiratory symptoms are not responding to initial medical therapy. Tracheal squamous cell carcinoma typically occurs more in men between the ages of 60 to 70 years and mostly in smokers. In contrast, tracheal adenoid cystic carcinomas have equal gender predisposition, occur between the ages of 40 and 50, and do not demonstrate any smoking association.[13]

Evaluation

Initial evaluation starts with a chest radiograph to rule out other pathologies. Visualization of a tracheal mass or narrowing was noted in only a minority of cases at presentation.[14] For these rare tumors, a high index of suspicion is essential for early diagnosis, paying close attention to subtle abnormalities like the mediastinal contours or tracheal air shadow sign. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest, with recent advances in imaging techniques and three-dimensional reconstruction, may allow for early detection of cancer and further assessing the degree and pattern of invasion. CT scan imaging can help to show polypoid lesions, focal stenosis, and/or circumferential wall thickening. CT scans or positron emission tomography (PET) scans are also used to identify the extent of the disease, including any distant metastasis, which may help determine the type of treatment.[15][16] However, adenoid cystic carcinoma and slow-growing mucoepidermoid tumors might have variable fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake on the PET scans.[17]

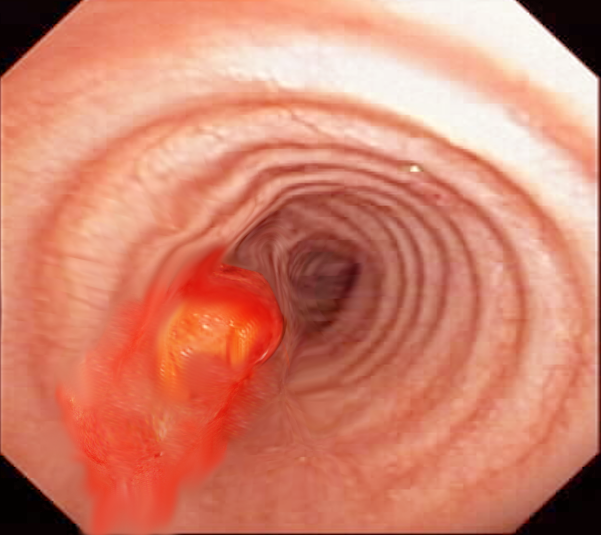

After the initial evaluation by imaging, bronchoscopy evaluation provides the opportunity for direct visualization of the mass and obtaining tissue biopsy for diagnosis. This is essential to differentiate between benign and malignant lesions. Endobronchial ultrasound allows for a better evaluation of the extent of wall invasion and enables the detection of paratracheal tumors invading the trachea; hence aids in the decision-making when assessing the resectability of the tumor.[18]

Spirometry can further provide information pertaining to the type of tracheal obstruction based on the flow volume loops. The characteristic flow volume loop patterns of large airway obstruction include fixed, intrathoracic, and variable extrathoracic patterns.[19] Laryngoscopy is useful for assessing patients with changes to the voice, including hoarseness, weak voice, or signs of aspiration.

Treatment / Management

Resectable Tumors

Surgical resection is the treatment of choice for malignant tracheal lesions whenever possible. The resectability of primary tracheal tumors is assessed using evaluation techniques described above, including CT imaging and bronchoscopy with ultrasound. However, several factors play a role in determining the possibility of safe resection followed by appropriate reconstruction with primary anastomosis. Though up to half of tracheal length can be safely resected, this depends on individual patient characteristics like weight, age, neck mobility, and underlying comorbidities. Given the rarity of these tumors, it is essential that patients be referred to high-volume, tertiary centers for proper evaluation and treatment in a multidisciplinary setting. Five-year survival is 50% for patients treated with surgery, while it is only 10% for patients who are not surgical candidates.[12](B3)

The surgical preparation and anesthetic management for the resection of primary tracheal tumors are standard as used for upper airway procedures and include securing a peripheral arterial line, bladder catheterization, securing an airway, using muscle relaxers, providing appropriate ventilation during the resection using suitable cuffed tubes or catheters for jet ventilation.[20] The resection technique itself includes dissection along the anterior midline plane to mobilize the trachea while visualizing the recurrent laryngeal nerves and lateral blood supply to the trachea while avoiding them. The tracheal dissection is typically circumferential and distal to the tumor. The tumor containing part of the trachea is then divided into a cephalic orientation and removed. Radical lymph node dissection or evaluation is avoided given the fact that the paratracheal lymph nodes and the tracheal blood supply are closely entwined, and this could devoid the trachea of its blood supply resulting in problems with the healing of the anastomosis. Reconstruction techniques after such surgical resection techniques are used when the tension on the anastomosis is excessive and include release maneuvers.[21] The most common technique utilized in these situations is the Montgomery suprahyoid release to gain tracheal length.[22]

Adjunctive therapy with radiation is recommended for all types of tracheal cancers that are locally advanced and in tumors that may not have disease-free margins post-surgery. In patients with squamous cell carcinoma, radiotherapy correlates with improved survival, even in the absence of cancer cells in the resected margins.[23][24][23] Although adenoid cystic carcinoma is less radiosensitive, however, radiation is associated with better outcomes and decreased recurrence rates. In nonsurgical candidates, radiotherapy or combined platinum-based concurrent chemoradiotherapy is considered the first line of treatment and is a palliative option in advanced disease.[25][26] (A1)

Because of the risk of anastomotic leakage or persistence of anastomotic tension after surgery, adjuvant radiation is offered at least two months after the surgery or sometimes even delayed further as determined by any concerns for anastomotic integrity. Aside from positive margins, additional high-risk factors that help identify appropriate candidates for adjuvant radiotherapy include T3 to T4 staging of cancer, perineural invasion, lymphovascular invasion, or extracapsular extension of the tumor.

The literature lacks randomized controlled trials examining chemotherapy in patients with tracheal cell cancers, and the role of chemotherapy remains unclear. However, cisplatin-based chemotherapy is combined with radiotherapy for unresectable diseases or after surgery for bronchogenic carcinomas, especially targeting more peripheral lung cancer.[27](B3)

In poor surgical candidates or those with advanced unresectable tumors, interventional procedures such as stent placement are sometimes necessary, in combination with radiation as palliative therapy. Stents are also used in emergencies in patients presenting with complete or significant obstruction of airways as a bridge to surgery.[12] Given the rarity of primary tracheal cancers, the optimum approach for unresectable or metastatic cancers has not been established. However, in unresectable, nonmetastatic cases, concurrent platinum-based chemoradiation is employed.[28][27] In patients with metastatic squamous cell carcinoma, systemic therapy is offered in the lines of those used for lung or head and neck squamous cell carcinomas, including immunotherapies.[29] Patients with metastatic adenoid cystic carcinomas can be typically observed if they remain asymptomatic since there is no evidence of chemotherapy altering the course of the disease or its outcomes. (B3)

Surveillance

Disease recurrence has been seen in patients with primary tracheal cancer after surgery, with a 10-year-recurrence-free survival rate of 60%. In squamous cell carcinoma of the trachea, given its association with smoking and due to the "field cancerization" effect, second primary squamous cell cancers may arise elsewhere in the airway. Adenoid cystic carcinomas, on the other hand, are associated with late local recurrences and metastases. Therefore, regular endoscopic surveillance is recommended, although the ability and options to undergo additional interventions might be limited, especially in patients who received adjuvant high-dose radiotherapy.

Differential Diagnosis

Benign Tumors

- Paraganglioma

- Pyogenic ganglioma

- Benign vascular tumors

- Squamous papilloma

- Pleomorphic adenoma

- Peripheral nerve sheath tumor

- Schwannoma

- Atypical schwannoma

- Plexiform neurofibroma

- Hemangiomatous malformations

- Leiomyoma

- Plasma cell granuloma

Malignant Tumors

- Small cell carcinoma

- Large cell carcinoma

- Adenocarcinoma

- Adenosquamous carcinoma

- Carcinoids

- Melanoma

- Lymphoma

- Chondrosarcoma

- Spindle cell sarcoma

- Leiomyosarcoma

- Invasive fibrous tumor

- Malignant fibrous histiocytoma

- Psudosarcoma

- Mucoepidermoid carcinoma

Staging

No established staging system is specific for tracheal cancers. Some investigators employ the tumor, nodes, and metastasis (TNM) staging system for disease staging. However, due to the low incidence of these tumors, no set tumor, nodes, or metastasis TNM staging exists for tracheal tumors. A recent study performed in 2022 showed prognostic differences in patients who were distinguished based on TNM classification. The study showed the benefit of early diagnosis and the extent of the tumor in aiding with the treatment based on tumor resectability.[30]

Prognosis

The five-year survival of primary tracheal cancer depends on the type of tumor. Adenoid cystic carcinomas carry a better prognosis than squamous cell carcinomas, with a significant difference in 5-year survival between both tumors (74% vs. 13%). The favorable prognosis for adenoid cystic carcinomas reflects the slower growth and a more prolonged natural course of this tumor. Early diagnosis and definitive surgical therapy before the local or distant spread of cancer are associated with a favorable prognosis and increased survival. Five-year survival was 4%, 25%, and 47% in distant metastasis, regional disease, and localized cancers, respectively, in an extensive population-based registry.[3][31]

Complications

Complications related to primary cancer growth and invasion of local organs include airway obstruction, dysphagia, and hoarseness. Postoperative complications include failed anastomotic healing, infections, cancer recurrence, and reduced quality of life, especially with resectioning large segments of the trachea leading to a significant limitation in neck extension.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Following treatment, patients can expect to have regular follow-ups. Patients must understand that they must report any new symptoms that may arise between appointments. Patients may also need psychological support to deal with their illness, and these resources should be provided to help them manage any feelings of anger, resentment, guilt, anxiety, and fear.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Primary tracheal cancers are rare and require a high index of suspicion for diagnosis, especially in the absence of response to treatment of other alternative diagnoses such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, or infections. Squamous cell carcinoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma are the most common histopathological types. Computed tomography is the imaging modality of choice for initial evaluation, and bronchoscopy provides the chance for direct visualization and pathologic cancer diagnosis. Surgery with complete tumor resection should be performed whenever possible as it correlates with increased 5-year survival. Adjuvant radiotherapy is helpful in most cases. In advanced unresectable diseases, radiation and bronchoscopic interventions such as stenting of the trachea serve as palliative therapy, while concurrent platinum-based chemoradiation can be used for disease control in nonmetastatic unresectable cancers.

Care is optimized by having an interprofessional healthcare team, including primary care clinicians (MDs, DOs, NPs, and PAs), pulmonologists, radiologists, pathologists, thoracic surgeons, radiation oncologists, and medical oncologists. Clinicians need to keep meticulous records of all interactions and interventions with the patient so that everyone on the care team has access to the same updated and accurate patient information. Specialized oncology-trained nurses also play a crucial role in patient care and management, as they counsel patients and facilitate communication between the various disciplines involved in the case. Surgical outcomes are noted to be superior when treated ta high-volume tertiary-level centers. [Level 4] The interprofessional model will result in the best possible patient outcomes. [Level 5]

Media

References

Honings J,van Dijck JA,Verhagen AF,van der Heijden HF,Marres HA, Incidence and treatment of tracheal cancer: a nationwide study in the Netherlands. Annals of surgical oncology. 2007 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 17139460]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHonings J,Gaissert HA,van der Heijden HF,Verhagen AF,Kaanders JH,Marres HA, Clinical aspects and treatment of primary tracheal malignancies. Acta oto-laryngologica. 2010 Jul; [PubMed PMID: 20569185]

Urdaneta AI,Yu JB,Wilson LD, Population based cancer registry analysis of primary tracheal carcinoma. American journal of clinical oncology. 2011 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 20087156]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGaissert HA,Grillo HC,Shadmehr MB,Wright CD,Gokhale M,Wain JC,Mathisen DJ, Long-term survival after resection of primary adenoid cystic and squamous cell carcinoma of the trachea and carina. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2004 Dec; [PubMed PMID: 15560996]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMacchiarini P, Primary tracheal tumours. The Lancet. Oncology. 2006 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 16389188]

Honings J,Gaissert HA,Ruangchira-Urai R,Wain JC,Wright CD,Mathisen DJ,Mark EJ, Pathologic characteristics of resected squamous cell carcinoma of the trachea: prognostic factors based on an analysis of 59 cases. Virchows Archiv : an international journal of pathology. 2009 Nov [PubMed PMID: 19838727]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHonings J,Gaissert HA,Weinberg AC,Mark EJ,Wright CD,Wain JC,Mathisen DJ, Prognostic value of pathologic characteristics and resection margins in tracheal adenoid cystic carcinoma. European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery : official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 2010 Jun [PubMed PMID: 20356756]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMoores D,Mane P, Pathology of Primary Tracheobronchial Malignancies Other than Adenoid Cystic Carcinomas. Thoracic surgery clinics. 2018 May [PubMed PMID: 29627048]

Junker K, Pathology of tracheal tumors. Thoracic surgery clinics. 2014 Feb [PubMed PMID: 24295655]

Dean CW,Speckman JM,Russo JJ, AIRP best cases in radiologic-pathologic correlation: adenoid cystic carcinoma of the trachea. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2011 Sep-Oct [PubMed PMID: 21918054]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBrand-Saberi BEM, Schäfer T. Trachea: anatomy and physiology. Thoracic surgery clinics. 2014 Feb:24(1):1-5. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2013.09.004. Epub 2013 Nov 9 [PubMed PMID: 24295654]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSherani K,Vakil A,Dodhia C,Fein A, Malignant tracheal tumors: a review of current diagnostic and management strategies. Current opinion in pulmonary medicine. 2015 Jul; [PubMed PMID: 25978628]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMadariaga MLL,Gaissert HA, Overview of malignant tracheal tumors. Annals of cardiothoracic surgery. 2018 Mar; [PubMed PMID: 29707502]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHonings J,Gaissert HA,Verhagen AF,van Dijck JA,van der Heijden HF,van Die L,Bussink J,Kaanders JH,Marres HA, Undertreatment of tracheal carcinoma: multidisciplinary audit of epidemiologic data. Annals of surgical oncology. 2009 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 19037701]

Javidan-Nejad C, MDCT of trachea and main bronchi. Radiologic clinics of North America. 2010 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 19995634]

Seemann MD,Schaefer JF,Englmeier KH, Virtual positron emission tomography/computed tomography-bronchoscopy: possibilities, advantages and limitations of clinical application. European radiology. 2007 Mar; [PubMed PMID: 16909219]

Park CM,Goo JM,Lee HJ,Kim MA,Lee CH,Kang MJ, Tumors in the tracheobronchial tree: CT and FDG PET features. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2009 Jan-Feb [PubMed PMID: 19168836]

Tanaka F,Muro K,Yamasaki S,Watanabe G,Shimada Y,Imamura M,Hitomi S,Wada H, Evaluation of tracheo-bronchial wall invasion using transbronchial ultrasonography (TBUS). European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery : official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 2000 May; [PubMed PMID: 10814921]

Hyatt RE, Evaluation of major airway lesions using the flow-volume loop. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 1975 Sep-Oct [PubMed PMID: 1190673]

Hobai IA,Chhangani SV,Alfille PH, Anesthesia for tracheal resection and reconstruction. Anesthesiology clinics. 2012 Dec [PubMed PMID: 23089505]

Donahue DM,Grillo HC,Wain JC,Wright CD,Mathisen DJ, Reoperative tracheal resection and reconstruction for unsuccessful repair of postintubation stenosis. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 1997 Dec; [PubMed PMID: 9434688]

Montgomery WW, Suprahyoid release for tracheal anastomosis. Archives of otolaryngology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 1974 Apr; [PubMed PMID: 4594223]

Bernier J, Domenge C, Ozsahin M, Matuszewska K, Lefèbvre JL, Greiner RH, Giralt J, Maingon P, Rolland F, Bolla M, Cognetti F, Bourhis J, Kirkpatrick A, van Glabbeke M, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Trial 22931. Postoperative irradiation with or without concomitant chemotherapy for locally advanced head and neck cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2004 May 6:350(19):1945-52 [PubMed PMID: 15128894]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCooper JS, Pajak TF, Forastiere AA, Jacobs J, Campbell BH, Saxman SB, Kish JA, Kim HE, Cmelak AJ, Rotman M, Machtay M, Ensley JF, Chao KS, Schultz CJ, Lee N, Fu KK, Radiation Therapy Oncology Group 9501/Intergroup. Postoperative concurrent radiotherapy and chemotherapy for high-risk squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. The New England journal of medicine. 2004 May 6:350(19):1937-44 [PubMed PMID: 15128893]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceXie L,Fan M,Sheets NC,Chen RC,Jiang GL,Marks LB, The use of radiation therapy appears to improve outcome in patients with malignant primary tracheal tumors: a SEER-based analysis. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2012 Oct 1; [PubMed PMID: 22365629]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWebb BD,Walsh GL,Roberts DB,Sturgis EM, Primary tracheal malignant neoplasms: the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center experience. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2006 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 16427548]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAllen AM,Rabin MS,Reilly JJ,Mentzer SJ, Unresectable adenoid cystic carcinoma of the trachea treated with chemoradiation. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2007 Dec 1; [PubMed PMID: 18048830]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJoshi NP,Haresh KP,Das P,Kumar R,Prabhakar R,Sharma DN,Heera P,Julka PK,Rath GK, Unresectable basaloid squamous cell carcinoma of the trachea treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy: a case report with review of literature. Journal of cancer research and therapeutics. 2010 Jul-Sep [PubMed PMID: 21119264]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMaller B,Kaszuba F,Tanvetyanon T, Complete Tumor Response of Tracheal Squamous Cell Carcinoma After Treatment With Pembrolizumab. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2019 Apr [PubMed PMID: 30326234]

Piórek A,Płużański A,Teterycz P,Kowalski DM,Krzakowski M, Do We Need TNM for Tracheal Cancers? Analysis of a Large Retrospective Series of Tracheal Tumors. Cancers. 2022 Mar 25; [PubMed PMID: 35406437]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLloyd S,Yu JB,Wilson LD,Decker RH, Determinants and patterns of survival in adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck, including an analysis of adjuvant radiation therapy. American journal of clinical oncology. 2011 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 20177363]