Introduction

The trachea is a tube-like structure beginning at the base of the cricoid cartilage and extending to the carina. It has cervical and thoracic portions, separated at the level of the thoracic inlet above and below respectively. It includes 18 to 22 D-shaped rings which are cartilaginous anteriorly and laterally and membranous posteriorly. Blood supply to the cervical portions of the trachea comes from branches of the subclavian artery where they enter laterally and anastomose superiorly, inferiorly, and anteriorly. Thoracic portions receive their blood supply from the bronchial arteries which branch off the aorta. The trachea is near the esophagus, vagus nerve, recurrent laryngeal nerves, thyroid, carotid arteries, jugular veins, innominate arteries and veins, the pulmonary trunk, the azygos vein, and the aorta with the vertebra and spinal cord posteriorly.[1]

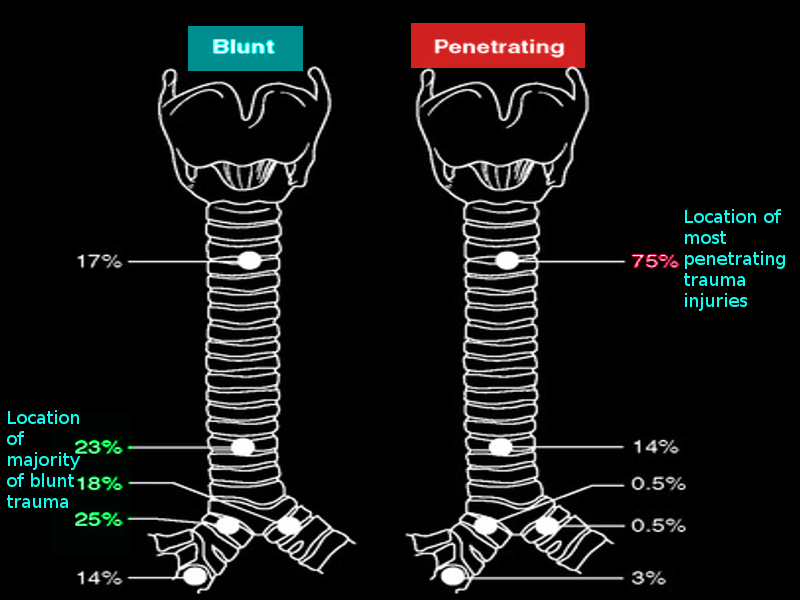

With so many vital structures adjacent to the trachea, the majority of patients with tracheal injuries may expire before arrival at an emergency department. The major causes of tracheal injury include iatrogenic, blunt trauma, penetrating trauma, inhalation and aspiration of liquids or objects.[2] The most common site for tracheal injuries from blunt trauma is within 2.5 cm of the carina.[3] Tracheal lacerations can be transverse, spiral, or longitudinal with varying degrees of tissue involvement.[4]

One of the most crucial factors for reducing morbidity and mortality is early detection.[5] With a high index of suspicion, the physical and radiographic signs most frequently seen with tracheal injury were dyspnea, pneumomediastinum, pneumothorax, and subcutaneous emphysema.[5] Proper airway management is vital. When appropriate, it is best achieved by awake intubation over a flexible bronchoscope with the placement of an endotracheal tube distal to the site of injury.[5] Management of laceration repair can then be accomplished either conservatively or surgically depending on the cause of the injury, the depth, and the concomitant injuries sustained.[4][6] Despite early recognition and appropriate management, potential complications include; decreased lung function, infection, vocal cord paralysis, and strictures.[3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Iatrogenic causes include percutaneous dilatational tracheostomy, endotracheal intubation, and rigid bronchoscopy. With endotracheal intubation, certain situations predispose the patient to complications including emergency, the skill of the operator, improper use of a stylet, use of a high-pressure cuff, and manipulation of the tube with a blocked cuff. Patient-specific risk factors for iatrogenic tracheal injury include age between 50 and 70, elevated BMI, female gender, and long term use of corticosteroids. Most iatrogenic tracheal injuries tend to occur in the posterior membranous portion of the trachea.[4]

Blunt trauma primarily affects the thoracic trachea. In the cervical trachea, blunt trauma will typically cause damage to the cartilaginous portions. For blunt thoracic trauma, three theories exist to explain the cause of tracheal injury. The first primarily occurs in crush injuries where increased force causes shortening of the anteroposterior axis and widening the transverse axis with lungs remaining in contact with the chest wall and causing increased tension on the carina and resultant separation. The second theory suggests that with the glottis closed increased pressure within the trachea causes rupture of the intercartilaginous membrane. The third suggests that rapid deceleration like that seen in motor vehicle accidents causes shearing forces between the more affixed carina and the looser lung tissue.[3]

Although penetrating trauma occurs more frequently in the cervical portions of the trachea, it can occur anywhere along the path of the trachea and involve any of the adjacent structures. More caution is necessary with penetrating gunshot wounds due to the force of the blast.[4]

Both inhalation and aspiration cause damage to the mucosal lining of the trachea, leading to inflammation, ulceration, and softening of the cartilaginous portions.[7]

Epidemiology

Currently, the incidence of tracheobronchial injury among trauma patients with chest and neck injuries, including those who died, is between 0.5 and 2%.[8] Four percent of penetrating neck injuries sustain tracheobronchial injury and less than 1 to 2% of penetrating chest injuries.[8] The incidence of tracheal injury has a male predominance from trauma with an average age in the twenties.[5] Considering endotracheal intubations, iatrogenic injuries of the trachea occur once in every 20000 to 75000 elective intubations, increasing up to 15% for emergent intubations.[8]

History and Physical

In a retrospective analysis of 20 patients with tracheobronchial injury, researchers identified 45% by history and physical.[5] Histories were consistent with blunt or penetrating trauma to the chest and/or neck, recent endotracheal procedures, and inhalation or aspiration of caustic chemicals or fumes. Clinical signs and symptoms consistent with tracheobronchial injury include but are not limited to respiratory failure, dyspnea, crepitus/subcutaneous emphysema, high riding hyoid bone, pneumomediastinum, Hamman sign, persistent pneumothorax, stridor, hemoptysis, dysphonia, or dysphagia.[4] Hamman sign is a crunchy, raspy sound heard in synchrony with the heart on auscultation. A large air leak and inability to expand the lung after tube thoracostomy, or desaturation after tube thoracostomy is indicative of tracheobronchial injury.[8] Many of these signs are also consistent with concomitant injuries to the neck and thorax so maintain a high degree of suspicion to ensure early detection.

Evaluation

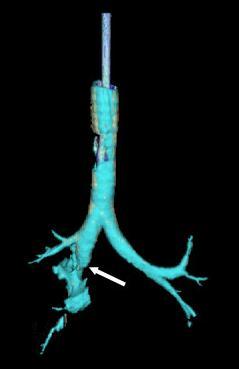

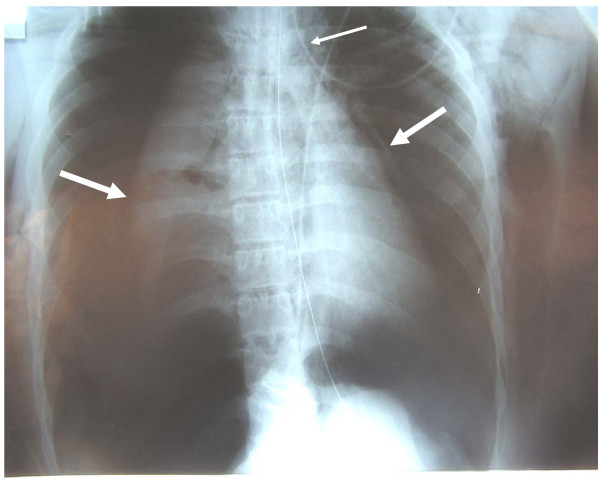

X-ray is the initial modality for the evaluation of the trauma patient and may show signs indicative of tracheal injury, including subcutaneous emphysema, pneumomediastinum, or a “fallen lung” sign. The “fallen lung” sign is where the lung presents in a dependent position held on to the hilum by its vascular attachments.[4] Ten to twenty percent of patients with tracheal injury may have no evidence thereof on plain radiographs.[9][4] CT imaging has proven to be effective in diagnosing tracheobronchial injury 71% of the time, and with MPR/3D reconstruction diagnostic accuracy has improved up to 94 to 100%. This modality has also led to virtual bronchoscopy reconstructions which are comparable to conventional bronchoscopy.[4] Bronchoscopy is the gold standard for the detection of tracheal injuries.[2]

Treatment / Management

When evaluating a patient with a tracheal injury early detection, proper airway management, and appropriate treatment of the trachea and possible concomitant injuries are key. As discussed previously early detection requires a high degree of suspicion, physical exam findings, and radiographic or bronchoscopic identification. Once a tracheal injury has been identified, the first question that needs to be addressed is what to do with the patient’s airway. The ideal method for securing the airway in patients with tracheal injury is the awake placement of an endotracheal tube over a flexible bronchoscope and inflation of the cuff distal to the site of injury. Patients with tracheal injury may benefit from awake intubation in order to limit apnea and loss of the smooth muscle tone. Paralysis for intubation may lead to the collapse of a trachea that is already distorted and traumatized and being held open by the surrounding musculature. In situations where the patient is rapidly desaturating, hemodynamically unstable, and/or awake intubation is not tolerated rigid bronchoscopy with inhalation induction may be the method of choice. This method is especially beneficial if clots, tissue, or strictures impair viewing the area of injury. However rigid bronchoscopy is more difficult in patients with cervical instability who are unable to extend the neck. Tracheostomy should be considered in patients with concomitant craniomaxillofacial injury or in whom previous attempts at endotracheal intubation were unsuccessful. Additionally, patients with penetrating cervical injuries could undergo the insertion of a tracheostomy tube directly through the site of injury thereby preserving tissue for future repair.[8]

Conservative management in select patients is superior to surgical treatments.[8] Injuries best treated conservatively are usually the result of iatrogenic injury, have lacerations less than 2 cm, have no concomitant injury, and can be stabilized without the persistence of symptoms.[4] Both Fuhrman and Cardillo have established guidelines to aid in deciding if a tracheal injury is amenable to conservative treatment or not.[4][6][10] For patients who are not good candidates for surgical repair application of surgical adhesive glue for lacerations under 5 mm has been utilized along with stenting.[11] In patients who tolerate jet insufflation and who have membranous posterior wall attachments, an endoluminal repair may prove effective.[4]

Stenting has become a mainstay of treatment for tracheal injuries. The two broad categories of stents are metallic and silicone with metallic stents having varying degrees of coating and both classes being offered in straight, T, and Y shapes to accommodate the variety of injuries that can occur. Placement of both classes of stents can be performed by a rigid or flexible bronchoscope. With regards to either modality ensure to secure the airway distal to the location requiring stenting and observe for potential complications. Complications of stents include migration, fracture, infection, biofilm formation, and obstruction with either defective mucus passage, or granulation tissue. Future advancements in stent technology may yield drug-eluting stents, 3-dimensional printed stents, and biodegradable products to reduce the complications seen with conventional stents.[12]

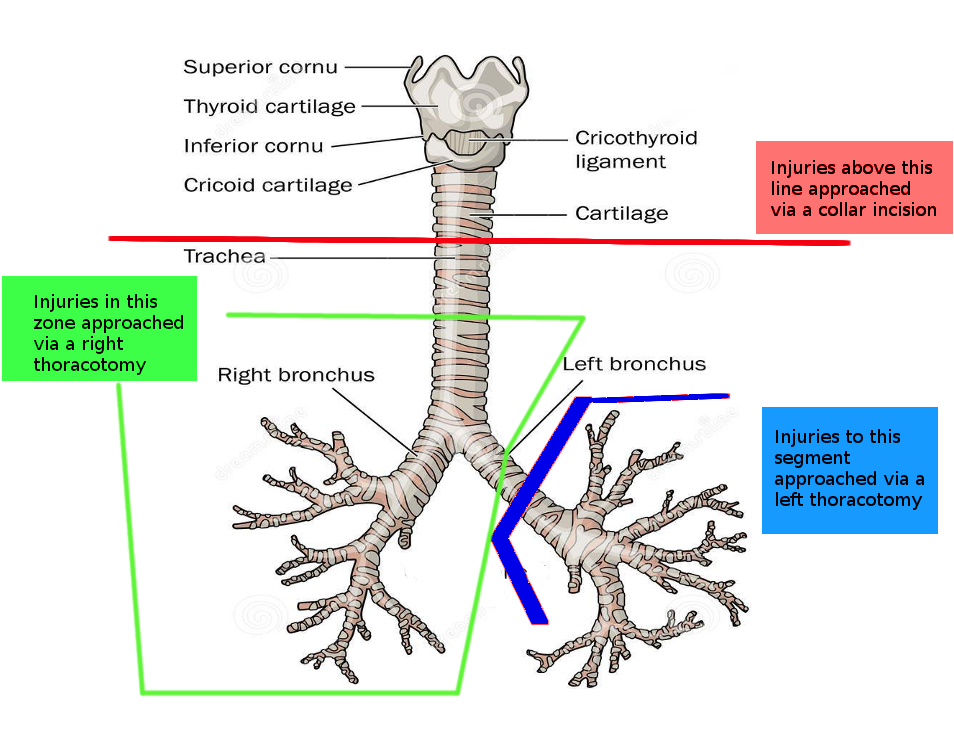

Surgical management even in patients with delayed identification of tracheal injury has proven beneficial in restoring lung function and reducing complications.[3] Location and concomitant injury guide the decision on approach. In general, cervical injuries can be approached through a collar incision.[4] Extension of the incision to the level of the second intercostal through the manubrium can provide access down to the level of the innominate artery and vein.[4] If exposure of the hemithorax or mediastinum is required a median partial sternotomy or clamshell incision could be utilized but does not provide better access to the trachea.[4] For tracheal injuries at the level of the carina or involvement of the bronchi including the middle portion of the left main bronchus, a right anterolateral or posterolateral thoracotomy may be used.[4] The distal portion of the left main bronchus could be approached through a left posterolateral thoracotomy if needed.[4]

Once access has been obtained to the injured area, carefully debride the wound margins in preparation for primary closure using a 3-0 or 4-0 absorbable suture. Transverse wounds should be closed using a simple interrupted suture. Longitudinal repairs are most amenable to a continuous suture. In circumstances where extensive damage has occurred, circumferential resection with end to end anastomosis may be necessary and except for injuries to the carina is preferred to partial debridement with attempted primary repair. When the blood supply is impaired and there is a concern for dehiscence covering with pericardial or mediastinal fat flaps could be of benefit. In all closures, an absorbable suture should be used with the knots on the outside to avoid granuloma and stricture formation and potential lifelong irritation.[4]

After repair, closed thoracic drainage and negative intrathoracic pressure may aid in the expansion of the lungs and occlusion of the repaired defect.[13] Consideration should also be given to head immobilization to reduce tension on repair for 1 to 2 weeks, continued antibiotic coverage, bronchoscopic assisted secretion removal, and incentive spirometry.[13] Steroids, proton pump inhibitors, and cough suppressants can also aid in relieving strain on healing tracheal injuries.[6][14]

Differential Diagnosis

With blunt and penetrating trauma being common causes of tracheal injury, adjacent structures are likely also to be involved. Concomitant injuries to the larynx, bronchi, lung parenchyma, the esophagus, the recurrent laryngeal nerve, vagus nerve, carotid arteries, jugular veins, pulmonary trunk, aorta, and surrounding musculature require clinical consideration.[1] These injuries can lead to hemo/pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, dysphonia, dysphagia, pneumonia, sepsis, bronchiectasis, atelectasis, multi-organ system failure, and stroke and significantly increase the mortality of tracheal injury.[3]

Prognosis

While mortality decreased from 36% before 1950 to 9% in 2001, prognosis greatly depends on early detection, the presence of concomitant injuries, and the cause of the injury.[8][3] Blunt tracheal injuries were associated with a better prognosis than crush injuries.[3] Forty to one hundred percent of fatal tracheal injuries were found to have concomitant injuries that were determined to be the cause of death.[3] Early detection and appropriate treatment yield satisfactory outcomes in over 90% of patients.[8]

Complications

While the immediate complication of tracheal injury is airway collapse, many additional complications need to be considered even with appropriate management. Pulmonary infections, sepsis, and multi-organ system failure are major contributors to mortality.[8] Atelectasis and bronchiectasis can contribute to lasting decreased pulmonary function.[3] Strictures, fistula, and continued dysphonia can also occur following treatment.[4] The adjacent course of the recurrent laryngeal nerve to the trachea predisposes patients to potential unilateral or bilateral nerve injury. Patients may experience permanent or temporary voice changes depending on the severity of the injury ranging from a contusion to avulsion. In all cases of tracheal injury with suspected recurrent laryngeal nerve injury effort should not be made to identify the laterality or extent due to the increased potential for iatrogenic injury.[15]

Deterrence and Patient Education

With iatrogenic and traumatic causes of tracheal injury predominating, there are areas where both patients and providers can work to decrease the incidence of this condition. Utilization of low-pressure cuffs on endotracheal tubes, correct endotracheal tube size, avoidance of over inflation, and appropriate use of stylets and bougies are a few of the things providers can do to avoid tracheal injury. For difficult intubations and suspected tracheal injury use of flexible bronchoscopes allow visualization of potential injury and avoidance of creating false passages and/or worsening of tracheal injury.[14]

Continued training and utilization of advanced trauma life support by healthcare providers will continue to reduce the mortality of tracheal injuries.[5] With motor vehicles playing a significant role in the incidence of blunt tracheal injury, continued advancements in safety features, including seatbelts and airbags that mitigate the frequency of injury will help.[14][4] The use of neck protection while participating in activities involving motorcycles or all-terrain vehicles could help avoid another area of traumatic injury.[14] Decreasing the incidence of suicide is an area that can help impact preventable tracheal injuries.[14]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Tracheal injury requires the collaborative efforts of multiple professionals. Care begins with emergency medical services to increase the number of tracheal injuries that survive en route to the emergency department.[5] This action must be followed by prompt recognition of the severity of the injury and appropriate management of the airway by the emergency staff to help stabilize the patient for further intervention. The extent of the injuries will require elucidation by direct visualization by an otolaryngologist or by review of imaging by a radiologist. For life-threatening injuries not amenable to conservative treatment consultation with a surgical specialist is needed. Many of these patients will require close management within an intensive care unit where pulmonologists and infectious disease staff may work to avoid potential complications after injury repair; this can be significantly aided by trauma and surgically trained specialty nursing staff. Some patients will require rehabilitation to regain pulmonary function and close follow up to ensure proper healing.

With 70 to 80% of medical errors occurring due to poor communication and understanding with a vast majority of those occurring in trauma situations, it is crucial to have good interprofessional collaboration. A Scopic review of interprofessional collaboration in trauma situations found successful teams to have fluid interactions, collaborative leaders, and post-trauma analysis. The interactions were further described as a transformation from individuals in a team with independent actions to a team with interdependent actions. Successful leaders were found to be collaborative amongst not only their own team but also between disciplines.[16] [Level IV] The primary motivator for improvement in these situations is improving the outcomes for patients, and an interprofessional team approach including clinicians, specialists, and trauma specialty-trained nursing staff can improve outcomes for patients with a tracheal injury. [Level V]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Tracheal Injury

Morgan Le Guen, Catherine Beigelman, Belaid Bouhemad, Yang Wenjïe, Frederic Marmion; modified by delldot on 12/17/09, Public Domain, via Wikipadia.org.

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Chest X-ray With Bilateral Pneumothoraces

Morgan Le Guen, Catherine Beigelman, Belaid Bouhemad, Yang Wenjïe, Frederic Marmion, Public Domain, via Wickipedia.org.

References

Minnich DJ, Mathisen DJ. Anatomy of the trachea, carina, and bronchi. Thoracic surgery clinics. 2007 Nov:17(4):571-85. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2006.12.006. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18271170]

Juvekar NM, Deshpande SS, Nadkarni A, Kanitkar S. Perioperative management of tracheobronchial injury following blunt trauma. Annals of cardiac anaesthesia. 2013 Apr-Jun:16(2):140-3. doi: 10.4103/0971-9784.109772. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23545871]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKiser AC, O'Brien SM, Detterbeck FC. Blunt tracheobronchial injuries: treatment and outcomes. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2001 Jun:71(6):2059-65 [PubMed PMID: 11426809]

Welter S. Repair of tracheobronchial injuries. Thoracic surgery clinics. 2014 Feb:24(1):41-50. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2013.10.006. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24295658]

Cassada DC, Munyikwa MP, Moniz MP, Dieter RA Jr, Schuchmann GF, Enderson BL. Acute injuries of the trachea and major bronchi: importance of early diagnosis. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2000 May:69(5):1563-7 [PubMed PMID: 10881842]

Cardillo G, Carbone L, Carleo F, Batzella S, Jacono RD, Lucantoni G, Galluccio G. Tracheal lacerations after endotracheal intubation: a proposed morphological classification to guide non-surgical treatment. European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery : official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 2010 Mar:37(3):581-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2009.07.034. Epub 2009 Sep 12 [PubMed PMID: 19748275]

Reid A, Ha JF. Inhalational injury and the larynx: A review. Burns : journal of the International Society for Burn Injuries. 2019 Sep:45(6):1266-1274. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2018.10.025. Epub 2018 Dec 8 [PubMed PMID: 30529118]

Prokakis C, Koletsis EN, Dedeilias P, Fligou F, Filos K, Dougenis D. Airway trauma: a review on epidemiology, mechanisms of injury, diagnosis and treatment. Journal of cardiothoracic surgery. 2014 Jun 30:9():117. doi: 10.1186/1749-8090-9-117. Epub 2014 Jun 30 [PubMed PMID: 24980209]

Chu CP, Chen PP. Tracheobronchial injury secondary to blunt chest trauma: diagnosis and management. Anaesthesia and intensive care. 2002 Apr:30(2):145-52 [PubMed PMID: 12002920]

Cheng J, Cooper M, Tracy E. Clinical considerations for blunt laryngotracheal trauma in children. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2017 May:52(5):874-880. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2016.12.019. Epub 2016 Dec 30 [PubMed PMID: 28069269]

Madden BP. Evolutional trends in the management of tracheal and bronchial injuries. Journal of thoracic disease. 2017 Jan:9(1):E67-E70. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2017.01.43. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28203439]

Flannery A, Daneshvar C, Dutau H, Breen D. The Art of Rigid Bronchoscopy and Airway Stenting. Clinics in chest medicine. 2018 Mar:39(1):149-167. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2017.11.011. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29433711]

Zhao Z,Zhang T,Yin X,Zhao J,Li X,Zhou Y, Update on the diagnosis and treatment of tracheal and bronchial injury. Journal of thoracic disease. 2017 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 28203437]

Henry M, Hern HG. Traumatic Injuries of the Ear, Nose and Throat. Emergency medicine clinics of North America. 2019 Feb:37(1):131-136. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2018.09.011. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30454776]

Minard G, Kudsk KA, Croce MA, Butts JA, Cicala RS, Fabian TC. Laryngotracheal trauma. The American surgeon. 1992 Mar:58(3):181-7 [PubMed PMID: 1558336]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceCourtenay M, Nancarrow S, Dawson D. Interprofessional teamwork in the trauma setting: a scoping review. Human resources for health. 2013 Nov 5:11():57. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-11-57. Epub 2013 Nov 5 [PubMed PMID: 24188523]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence