Introduction

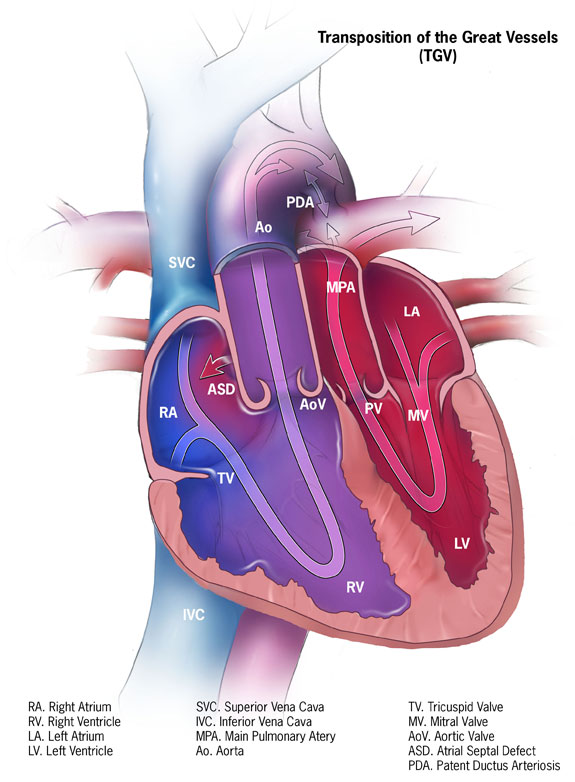

Transposition of the great arteries (TGA) is a pediatric cardiac congenital defect arising from an embryological discordance between the aorta and pulmonary trunk. During cardiac development, the conotruncal septum spirals toward the aortic sac thus dividing the truncus arteriosus into the pulmonary and aortic channels. These channels then become the pulmonary arteries and aorta, respectively. TGA occurs when the conotruncal septum fails to follow its spiral course and instead forms in a linear orientation. Consequently, the aorta arises from the right ventricle and the pulmonary trunk arises from the left ventricle. The most common form of TGA is referred to as dextro-TGA (D-TGA) which is characterized by the right ventricle being positioned to the right of the left ventricle and the aorta arising anterior and rightward to the pulmonary artery thus forming two parallel circuits. See Image. Dextro-Transposition of the Great Arteries (d-TGA). In the systemic circuit, deoxygenated blood returns to the right atrium pass through the tricuspid valve and is then forced back into systemic circulation by contraction of the right ventricle and passage into the aberrantly developed aorta. The second circuit is a pulmonary circuit in which oxygenated blood from the pulmonary veins drains into the left atrium, passes through the mitral valve, and is then forced back into the lungs via contraction of the left ventricle and through the pulmonary arteries. Patients typically present with cyanosis during the first 30 days of life. Complete parallel circuits are incompatible with life and thus require a patent ductus arteriosus and ventriculoseptal defect that allows mixing of oxygen-rich and oxygen-poor blood. [1]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The etiology for transposition of the great arteries is unknown; however, it is presumed to be multifactorial. Currently, there are two main theories regarding the embryological mechanisms of TGA development:

- De la Cruz proposed the theory that the aortopulmonary septum fails to spiral at the level of the infundibulum thus causing a linear development of the septum and TGA. [2]

- The second theory, proposed by Goor and Edwards, suggests that TGA is caused by abnormal resorption or underdevelopment of the subpulmonary conus, with persistence of the subaortic conus. [3]

Epidemiology

The prevalence of TGA is 4.7 per 10,000 live births. TGA accounts for three percent of all congenital heart disease and 20 percent of cyanotic heart disease.[4]

Pathophysiology

Knowledge of normal conotruncal septum formation facilitates understanding of D-TGA development. In the fifth week of gestation, opposing pairs of ridges form in the truncus arteriosus. These ridges are termed the right superior truncus swelling and the left inferior truncus swelling. The right superior truncus swelling grows distally and to the left while the left inferior truncus swelling grows distally and to the right. The result is twisting of the swellings around each other and the foreshadowing of the anatomically normal spiral septum.

Simultaneously, swellings in the dorsal and ventral walls of the conus cordis appear and grow toward each other and distally. Eventually, these swellings fuse with each other, as well as the truncus septum, thus dividing the conus cordis into anterolateral (right ventricular outflow tract) and posteromedial (left ventricular outflow tract) portions.

Equally important to septal formation, is the migration of neural crest cells through pharyngeal arches three, four, and six, and to the heart. There, they contribute to endocardial cushion formation in the truncus arteriosus and conus cordis, as well as lengthening of the outflow tracts. Any insult to the migration of neural crest cells can cause tetralogy of Fallot, truncus arteriosus, and TGA. It is not uncommon to see cardiac and craniofacial defects in the same individual since neural crest cells also contribute to craniofacial development.

Transposition of the great arteries occurs when the aorticopulmonary septum fails to spiral. This can be due to defects in the maturation of the right superior truncus swelling and the left inferior truncus swelling, fusion of the conus swellings with the aorticopulmonary septum, or adversities in neural crest development or migration.

The pathological defects in D-TGA cause a detrimental change in cardiac physiology. Due to the existence of two parallel circuits, deoxygenated blood continues to circulate systemically, and oxygenated blood continually flows through the pulmonary circuit. Parallel channels are incompatible with life unless mixing between deoxygenated and oxygenated blood occurs. Mixing can occur via an atrial or ventricular septal defect, patent ductus arteriosus, or through collateral bronchopulmonary circulation. Interventional cardiologists may also perform a balloon atrial septostomy (BAS) to facilitate mixing between the atria. [1]

Several common cardiac anomalies that can occur in patients with D-TGA can include:

- Ventriculoseptal defects

- Left ventricular outflow tract obstruction

- Mitral and tricuspid valve abnormalities

- Coronary artery variations

A lesser known form of TGA is levo-TGA (L-TGA). In this case, the left ventricle is positioned to the right of the right ventricle. Mainly, the ventricles are on opposite sides of the heart. The pulmonary trunk and aorta arise in their anatomically correct orientations, however, since the ventricles are reversed, the aorta is fused with the right ventricle, and the pulmonary trunk is combined with the left ventricle. The resultant flow of blood in a patient with L-TGA is as follows: Deoxygenated blood enters the anatomically correct right atrium, passes through the mitral valve into the left ventricle, and is pumped into the pulmonary trunk to the lungs. From the lungs, the oxygenated blood enters the left atrium, passes through the tricuspid valve, and into the right ventricle where blood is then pumped into the aorta. Since the flow of blood in patients with L-TGA passes through the normal systemic and pulmonary circuits, L-TGA is sometimes termed anatomically correct TGA. [5]

History and Physical

Antenatally, TGA is challenging to diagnose. Screening ultrasounds do not routinely reveal TGA in-utero.

Postnatal:

The clinical features of D-TGA are solely dependent on the degree of mixing between the parallel circuits. Most patients present with signs and symptoms during the neonatal period (first 30 days of life). The following are the typical clinical manifestations of TGA:

- Cyanosis: The degree of cyanosis is dependent on the amount of mixing between the two parallel circuits. Factors affecting intracardiac mixing include the size and presence of an ASD or VSD. Cyanosis is not affected by exertion or supplemental oxygen. [6]

- Tachypnea: Patients usually have a respiratory rate higher than 60 breaths per minute but without retractions, grunting, or flaring and appear comfortable.

- Murmurs: murmurs are not typically present unless a small VSD or pulmonic stenosis exists. A murmur resulting from a VSD will be pansystolic and prominent at the lower left sternal border. Pulmonic stenosis causes a systolic ejection murmur at the upper left sternal border. [7]

Patients with L-TGA are typically unaffected until later in life when the right ventricle can no longer compensate for the increased afterload of the systemic circulation. These patients present with signs and symptoms of heart failure. [7]

Evaluation

As previously stated, D-TGA is difficult to detect on fetal ultrasound due to the absence of differences in ventricle size. [8] Postnatally, when a cardiac disease is suspected based on clinical exam, echocardiography is performed. Echocardiography will reveal the aberrant origins of the aorta and pulmonary trunk as well as any associated intracardiac defects. Other studies often performed include:

- Electrocardiography: Often normal but may show right axis deviation and right ventricular hypertrophy

- Chest radiography: The classic radiographic features of TGA is an “egg on a string” appearance.

- Cardiac catheterization: Angiography is rarely used to diagnose TGA; however, it is the gold standard for elucidating the origins of the coronary arteries. Cardiac catheterization is routinely used in D-TGA to perform a balloon septostomy in patients with severe cyanosis.[9]

Treatment / Management

Initial management of patients with D-TGA centers on ensuring adequate oxygenation. Prostaglandin E1 administration stabilizes patients by attempting to keep the ductus arteriosus patent and performing a balloon atrial septostomy (BAS). Once the patient is hemodynamically stable, corrective surgery can be performed. [10] [11](B3)

Surgical repair of D-TGA is usually undertaken within the first week of life. There are currently two commonly used surgical procedures for D-TGA:

- Arterial switch operation (ASO): The arterial switch operation is the standard procedure for patients with D-TGA without major pulmonic stenosis. During the ASO, the surgeon will transect both the pulmonary trunk and aorta then translocate them to their anatomically correct positions. The coronary arteries are mobilized and reimplanted into the aortic trunk. If a VSD is present., it is also repaired during this time. [12]

- Rastelli procedure: The Rastelli procedure is indicated in patients presenting with D-TGA, a large VSD, and pulmonary stenosis. During this procedure, the VSD is closed using a baffle. By doing so, oxygenated blood from the left ventricle is directed into the aorta. A conduit is then placed from the right ventricle to the pulmonary artery thus shunting deoxygenated blood into the pulmonary artery. [13] (B3)

Other corrective procedures exist including the Mustard and Senning procedure, Nakaidoh procedure, Réparation à l'Etage ventriculaire (REV) procedure, and Yasui procedure however these are less commonly performed. [14](B2)

Differential Diagnosis

- Double-Outlet Right Ventricle

- Tricuspid Atresia

- Pulmonary Atresia

- Tetralogy of Fallot

- Total anomalous pulmonary venous return

- Truncus arteriosus

Prognosis

The prognosis for patients with D-TGA is generally excellent following surgical correction. Current survival rates are greater than 90%. The ASO has the best long-term survival and functional outcome. Some studies report a >95% rate survival at fifteen to twenty-five years following discharge. [15][16]

Complications

Several complications can result following corrective operations. These include:

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients with corrected D-TGA have slightly reduced exercise capacity. Some predictors of poor exercise performance include VSD repair, decreased left ventricular function, and repair before the development of the ASO. Reduced exercise capacity has not been shown to affect activities of daily living. [19]

Studies have also shown that patients who underwent ASO are more likely to have a neurodevelopmental impairment. One center reports that 65% of adolescents who experienced ASO as infants required special education services. The same center also reports that patients with surgically corrected ASO were more likely to have attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). The American Heart Association (AHA) recommends that children who underwent corrective surgery for D-TGA undergo continued screening and referral for neurodevelopmental impairment. [20]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The management of dextro-transposition of the great arteries can be challenging. While the correction of D-TGA is mostly the responsibility of a pediatric cardiothoracic surgeon, other specialists need to be involved in the care of the patient. Interventional pediatric cardiology needs to be consulted immediately for evaluation of cyanosis in a newborn which may facilitate the administration of prostaglandin E1 and balloon atrial septostomy. Interventional cardiology will also be able to concomitantly perform angiography to determine which anomalies of the coronary arteries are present. During treatment and following discharge, general pediatrics should be involved in the care of the infant for routine preventative care and neurodevelopmental screening. If deficiencies in neurodevelopment are found on annual testing, pediatric neurology and psychiatry will need to be consulted as well. The pharmacist pre-operatively should assist with medication reconciliation and pain management.

In order to obtain the best outcomes the nurse caring for a patient with corrected TGA will monitor for:

- Cardiac dysrhythmias or heart palpitations

- New heart murmurs, bruits, or extra heart sounds

- Fatigue, shortness of breath, or chest pain

- An increasing or decreasing blood pressure

- A decrease in oxygen saturation or development of cyanosis

- Swelling in the lower extremities

These symptoms may signal a serious complication, and should be addressed promptly with the clinical team.

Additionally, the nurse should expect to perform frequent physical, cardiac, respiratory, and neurological assessments, monitor vital signs and hemodynamics, and check fluid and electrolyte status. Patient and family education will be important during the pre-op, post-op, and discharge period. The best outcomes are achieved when the nurse, pharmacist, and surgeons work together to evaluate and monitor the patient and provide patient and family education in a coordinated manner. [Level V]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Warnes CA. Transposition of the great arteries. Circulation. 2006 Dec 12:114(24):2699-709 [PubMed PMID: 17159076]

de la Cruz MV, Arteaga M, Espino-Vela J, Quero-Jiménez M, Anderson RH, Díaz GF. Complete transposition of the great arteries: types and morphogenesis of ventriculoarterial discordance. American heart journal. 1981 Aug:102(2):271-81 [PubMed PMID: 7258100]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGoor DA, Edwards JE. The spectrum of transposition of the great arteries: with specific reference to developmental anatomy of the conus. Circulation. 1973 Aug:48(2):406-15 [PubMed PMID: 4726219]

Improved national prevalence estimates for 18 selected major birth defects--United States, 1999-2001. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2006 Jan 6; [PubMed PMID: 16397457]

Hornung TS, Bernard EJ, Celermajer DS, Jaeggi E, Howman-Giles RB, Chard RB, Hawker RE. Right ventricular dysfunction in congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries. The American journal of cardiology. 1999 Nov 1:84(9):1116-9, A10 [PubMed PMID: 10569681]

Oster ME, Aucott SW, Glidewell J, Hackell J, Kochilas L, Martin GR, Phillippi J, Pinto NM, Saarinen A, Sontag M, Kemper AR. Lessons Learned From Newborn Screening for Critical Congenital Heart Defects. Pediatrics. 2016 May:137(5):. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-4573. Epub 2016 Apr 15 [PubMed PMID: 27244826]

Van Praagh R, Geva T, Kreutzer J. Ventricular septal defects: how shall we describe, name and classify them? Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1989 Nov 1:14(5):1298-9 [PubMed PMID: 2808986]

Ravi P,Mills L,Fruitman D,Savard W,Colen T,Khoo N,Serrano-Lomelin J,Hornberger LK, Population trends in prenatal detection of transposition of great arteries: impact of obstetric screening ultrasound guidelines. Ultrasound in obstetrics & gynecology : the official journal of the International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2018 May [PubMed PMID: 28436133]

Gopalakrishnan A, Krishnamoorthy KM, Sivasubramonian S. Balloon atrial septostomy at the bedside versus the catheterisation laboratory. Cardiology in the young. 2019 Mar:29(3):454. doi: 10.1017/S1047951118002214. Epub 2019 Jan 28 [PubMed PMID: 30688192]

Freed MD, Heymann MA, Lewis AB, Roehl SL, Kensey RC. Prostaglandin E1 infants with ductus arteriosus-dependent congenital heart disease. Circulation. 1981 Nov:64(5):899-905 [PubMed PMID: 7285305]

Rashkind WJ, Miller WW. Creation of an atrial septal defect without thoracotomy. A palliative approach to complete transposition of the great arteries. JAMA. 1966 Jun 13:196(11):991-2 [PubMed PMID: 4160716]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJatene AD, Fontes VF, Paulista PP, Souza LC, Neger F, Galantier M, Sousa JE. Anatomic correction of transposition of the great vessels. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 1976 Sep:72(3):364-70 [PubMed PMID: 957754]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRastelli GC, Wallace RB, Ongley PA. Complete repair of transposition of the great arteries with pulmonary stenosis. A review and report of a case corrected by using a new surgical technique. Circulation. 1969 Jan:39(1):83-95 [PubMed PMID: 5782810]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHazekamp MG, Gomez AA, Koolbergen DR, Hraska V, Metras DR, Mattila IP, Daenen W, Berggren HE, Rubay JE, Stellin G, European Congenital Heart Surgeons Association. Surgery for transposition of the great arteries, ventricular septal defect and left ventricular outflow tract obstruction: European Congenital Heart Surgeons Association multicentre study. European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery : official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 2010 Dec:38(6):699-706. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.03.030. Epub 2010 May 13 [PubMed PMID: 20466558]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHutter PA, Kreb DL, Mantel SF, Hitchcock JF, Meijboom EJ, Bennink GB. Twenty-five years' experience with the arterial switch operation. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2002 Oct:124(4):790-7 [PubMed PMID: 12324738]

Tobler D,Williams WG,Jegatheeswaran A,Van Arsdell GS,McCrindle BW,Greutmann M,Oechslin EN,Silversides CK, Cardiac outcomes in young adult survivors of the arterial switch operation for transposition of the great arteries. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2010 Jun 29; [PubMed PMID: 20620718]

Gatzoulis MA, Walters J, McLaughlin PR, Merchant N, Webb GD, Liu P. Late arrhythmia in adults with the mustard procedure for transposition of great arteries: a surrogate marker for right ventricular dysfunction? Heart (British Cardiac Society). 2000 Oct:84(4):409-15 [PubMed PMID: 10995411]

Schwartz ML, Gauvreau K, del Nido P, Mayer JE, Colan SD. Long-term predictors of aortic root dilation and aortic regurgitation after arterial switch operation. Circulation. 2004 Sep 14:110(11 Suppl 1):II128-32 [PubMed PMID: 15364851]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSamos F, Fuenmayor G, Hossri C, Elias P, Ponce L, Souza R, Jatene I. Exercise Capacity Long-Term after Arterial Switch Operation for Transposition of the Great Arteries. Congenital heart disease. 2016 Mar-Apr:11(2):155-9. doi: 10.1111/chd.12303. Epub 2015 Nov 11 [PubMed PMID: 26556777]

Marino BS, Lipkin PH, Newburger JW, Peacock G, Gerdes M, Gaynor JW, Mussatto KA, Uzark K, Goldberg CS, Johnson WH Jr, Li J, Smith SE, Bellinger DC, Mahle WT, American Heart Association Congenital Heart Defects Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, and Stroke Council. Neurodevelopmental outcomes in children with congenital heart disease: evaluation and management: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012 Aug 28:126(9):1143-72 [PubMed PMID: 22851541]