Introduction

Trichinosis or trichinellosis is a helminth infection primarily contracted from poor or improper preparation of food. Pork and its products are the primary sources of infection.[1] It can be potentially fatal, but more commonly is a self-limiting disease.[2] Discovery of trichinosis is attributed to Sir Richard Owen and Sir James Paget who in 1835, observed a mass of worms lining the diaphragm of a cadaver. It is a persistent public health issue in countries where there is high pork consumption.[3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

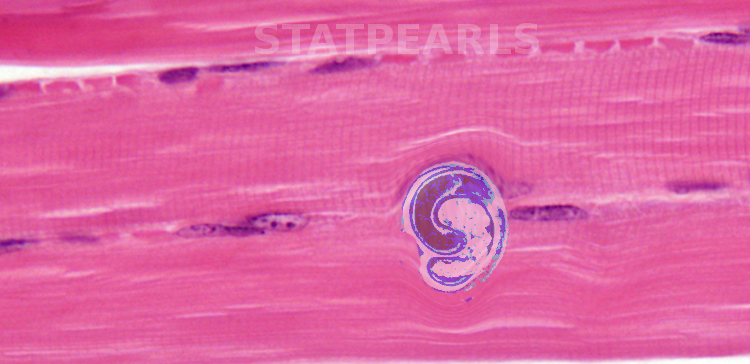

Trichinosis occurs from a nematode from the genus Trichinella. The parasites alternate between skeletal muscle stages and enteric stages during their life cycle within their host. The life cycle begins with the enteral phase when the host eats the infected meat. Digestive enzymes in the stomach dissolve the capsule releasing the larvae into the small intestine where they invade columnar epithelium. Larvae then pass into the tissue and enter the lymphatics eventually being released into general circulation via the thoracic duct. When they enter the muscle fibers from the capillaries, they encyst and become infective within 15 days. They can remain from months to years to the entire life of the host. There are eleven known species within the genus Trichinella. These eleven species subdivide into those that invade host muscle cells and encapsulate (surrounded by a collagen capsule) and those that do not encapsulate. Trichinella Spiralis belongs to the encapsulated group and causes most human infections and deaths from trichinosis.[4]

Epidemiology

Trichinella, the intestinal roundworm that causes trichinosis is primarily seen in raw or insufficiently cooked commercial pork, specifically, domestic and sylvatic swine (Sus scrofa). Other common hosts are synanthropic animals like cats, dogs, brown rats, and armadillos. It can, however, be acquired from wild game as well, particularly meat that has not been frozen or cooked properly. Since 1975, Walrus and bear meat have shown increased associations with trichinosis.[2] Due to its high infectivity and global distribution of pork meat, Trichinella can be found in the tropics all the way to the Arctic. The CDC estimates 10,000 cases of trichinosis occur worldwide every year. Cases in the United States were 400 per year on average in the 1940s but decreased to 20 cases on average by 2010.[5]

Pathophysiology

During the acute phase of infection, three major cell modifications occur:

The creation of a 'nurse cell' from the transformation of a host cell and disappearance of sarcomere myofibrils

- The larvae become encapsulated (if it is an encapsulated species)

- The infected cell forms a capillary network around it

- Additionally, the sarcoplasm becomes basophilic; there is a central displacement of the cell nucleus, and the number and size of the nucleoli increase

Trichinella larvae and their metabolites cause an immunological reaction from infiltrating inflammatory cells (eosinophils, mast cells, lymphocytes, monocytes). Eosinophils release the enzymes histaminase and arylsulfatase. Increased permeability of capillaries occurs from the release of histamine, serotonin, bradykinin, and prostaglandins PGE2, PGD2, PGJ2; this leads to tissue edema, especially around the eyes. The inflammatory processes also lead to vasculitis and microvascular thrombi. Increased production of IgE leads to allergic manifestations such as a cutaneous rash and edema.

History and Physical

No pathognomonic signs exist for trichinosis. Symptoms of Trichinella depend on the current stage of infection. During the enteral (intestinal) phase, the initial symptoms are mild transient diarrhea and nausea (from the intestinal invasion of the larvae), vomiting, upper abdominal pain, low-grade fever, and malaise. These begin 1-2 days after ingestion of infected meat. From 2-6 weeks after ingestion, intestinal symptoms disappear, and symptoms from the parenteral stage (skeletal muscle) appear. They include but are not limited to periorbital or facial edema, diffuse myalgia, and a paralysis-like state. The severity of disease is in correlation with the number of larvae ingested.[5]

Evaluation

Because the symptoms of the enteral phase are similar to other enteral disorders, it is easy to misdiagnose. Muscle biopsy usually reveals larvae in heavy infections. If the biopsy is attempted before the larvae begin to coil, the worms may be confused as muscle tissue fragments.[6] Serology confirms suspected trichinosis infection when anti-Trichinella IgG antibodies are detected. ELISA is a primary screening test with Western blot used as the confirmatory assay from excretory/secretory antigens (ESA). ESA recognizes an infection caused by any Trichinella taxa, but cannot provide the specific species causing the infection.[7] IgG-ELISA reaches 100% sensitivity on day 50 of infection but has a high number of false negatives in the early stages of the disease.[6][8]

Treatment / Management

Once a diagnosis of trichinosis is confirmed, therapy implementation should begin as soon as possible. If given within the first 3 days of infection, it prevents muscular invasion and disease progression. The primary drug treatment for trichinosis is antihelminthics. These include albendazole and mebendazole. Albendazole has been shown to reach adequate plasma levels and does not require monitoring whereas mebendazole plasma levels can vary from patient to patient and requires individual monitoring and dosing. The recommended dose of albendazole is 400 mg two times a day for 8 to 14 days. The recommended dose for mebendazole is 200 to 400 mg thrice daily for 3 days. Another dose of 400 to 500 mg should be given thrice daily for 10 days.

These doses are acceptable for children and adults but contraindicated in those <2 years or those who are pregnant. Pyrantel can is an option for children and pregnant women, given as a single dose of 10-20 mg/kg of body weight. It is only effective against intestinal larvae and does not affect newborn or muscle larvae. Primary chemotherapy for severe symptoms is prednisone given at a dose of 30-60 mg/day for 10-15 days.[9](B3)

Differential Diagnosis

Trichinosis presents with eosinophilia and intestinal symptoms in early infection. Therefore, several parasitic infections may cause the patients’ symptoms. These include:

- strongyloidiasis

- schistosomiasis

- hookworm

- gnathostomiasis

- lymphatic filariasis

- ascariasis

- whipworm

Prognosis

There is a poor prognosis for severe cases that include cerebral or cardiac complications. Even with therapy, the mortality rate in those with severe infection is 5%. Milder cases have a good prognosis with symptoms disappearing in 2-6 months.[9]

Complications

In acute illness, complications include stillbirths in infected pregnant women and vertical infection to the fetus. After successful treatment, patients have complained of menstrual irregularities, hearing disorders, weight loss, hair and nail loss, skin desquamation, aphonia, muscle stiffness, and hoarseness. Heart failure or CNS failure in the 3-5 weeks of infection can lead to death. Other causes of death have been pneumonitis, encephalitis, myocarditis, hypokalemia, obstruction of blood vessel circulation, and adrenal gland insufficiency. Long-term complications include generalized myalgia, ocular symptoms such as conjunctivitis, and various neuropathies. These may persist up to 10 years post-recovery.[2]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Clinical cases have decreased with education, but infections continue to occur in rural, urban, and less developed environments. Lack of education in the potential sources of trichinella such as meat from horses and wild game may be a factor. Also, cultural practices or exotic cuisines may be a factor.[10] There is evidence that contamination of plants on farms is also possible through water, manure, and wild animal incursions.[11] It is important for patients to know smoking or salting meat does not kill trichinella cysts. When freezing, meat that is less than 6 inches should remain frozen for 20 days at -15 C, for 10 days at -23 C, or 6 days at -30 C. It should be cautioned that wild game meat may be freeze-resistant if infected with the Trichinella nativa species. Cooked meat should reach a minimum internal temperature of 71.1 C (160 F) which would kill Trichinella larvae.[12]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Trichinosis is a difficult diagnosis, especially in areas where the infection is not endemic, and there has been no outbreak. In the first 3 to 4 weeks, patients present with nonspecific symptoms. These symptoms appear to be gastroenteritis, influenza, serious bacterial infection, heart failure, or acute coronary syndrome, leading to delayed diagnosis.[13]

It is vital for nurses and clinicians to not neglect detailed dietary and travel history, especially meat ingestion within the five weeks before symptoms began. Improvement in agricultural and food processing standards has minimized the risk of infection in commercial meat. Populations at the highest risk are those that consume undercooked or raw wild game meat or noncommercial sources of pork. In the US, recent outbreaks have been associated with wild boar, bear, walrus, and unspecified pork.[14]

Early diagnosis and treatment will reduce disease severity, but delay reduces the efficacy of antihelminthic drugs as larvae enter striated muscle. Trichinella larvae can survive in muscle tissue for many years so long-term follow-up may be necessary.[13]

Media

References

Wilson NO, Hall RL, Montgomery SP, Jones JL. Trichinellosis surveillance--United States, 2008-2012. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. Surveillance summaries (Washington, D.C. : 2002). 2015 Jan 16:64(1):1-8 [PubMed PMID: 25590865]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceZarlenga D, Wang Z, Mitreva M. Trichinella spiralis: Adaptation and parasitism. Veterinary parasitology. 2016 Nov 15:231():8-21. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2016.07.003. Epub 2016 Jul 2 [PubMed PMID: 27425574]

Kim G, Choi MH, Kim JH, Kang YM, Jeon HJ, Jung Y, Lee MJ, Oh MD. An outbreak of trichinellosis with detection of Trichinella larvae in leftover wild boar meat. Journal of Korean medical science. 2011 Dec:26(12):1630-3. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2011.26.12.1630. Epub 2011 Nov 29 [PubMed PMID: 22148002]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFarid AS, Fath EM, Mido S, Nonaka N, Horii Y. Hepatoprotective immune response during Trichinella spiralis infection in mice. The Journal of veterinary medical science. 2019 Feb 9:81(2):169-176. doi: 10.1292/jvms.18-0540. Epub 2018 Dec 12 [PubMed PMID: 30541982]

Petri WA Jr, Holsinger JR, Pearson RD. Common-source outbreak of trichinosis associated with eating raw home-butchered pork. Southern medical journal. 1988 Aug:81(8):1056-8 [PubMed PMID: 3043686]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTakahashi Y, Mingyuan L, Waikagul J. Epidemiology of trichinellosis in Asia and the Pacific Rim. Veterinary parasitology. 2000 Dec 1:93(3-4):227-39 [PubMed PMID: 11099839]

Nöckler K, Reckinger S, Broglia A, Mayer-Scholl A, Bahn P. Evaluation of a Western Blot and ELISA for the detection of anti-Trichinella-IgG in pig sera. Veterinary parasitology. 2009 Aug 26:163(4):341-7. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2009.04.034. Epub 2009 May 4 [PubMed PMID: 19473770]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSun GG, Liu RD, Wang ZQ, Jiang P, Wang L, Liu XL, Liu CY, Zhang X, Cui J. New diagnostic antigens for early trichinellosis: the excretory-secretory antigens of Trichinella spiralis intestinal infective larvae. Parasitology research. 2015 Dec:114(12):4637-44. doi: 10.1007/s00436-015-4709-3. Epub 2015 Sep 5 [PubMed PMID: 26342828]

Pozio E, Tamburrini A, La Rosa G. Horse trichinellosis, an unresolved puzzle. Parasite (Paris, France). 2001 Jun:8(2 Suppl):S263-5 [PubMed PMID: 11484375]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRhee JY, Hong ST, Lee HJ, Seo M, Kim SB. The fifth outbreak of trichinosis in Korea. The Korean journal of parasitology. 2011 Dec:49(4):405-8. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2011.49.4.405. Epub 2011 Dec 16 [PubMed PMID: 22355208]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRostami A, Gamble HR, Dupouy-Camet J, Khazan H, Bruschi F. Meat sources of infection for outbreaks of human trichinellosis. Food microbiology. 2017 Jun:64():65-71. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2016.12.012. Epub 2016 Dec 22 [PubMed PMID: 28213036]

Franssen F, Swart A, van der Giessen J, Havelaar A, Takumi K. Parasite to patient: A quantitative risk model for Trichinella spp. in pork and wild boar meat. International journal of food microbiology. 2017 Jan 16:241():262-275. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2016.10.029. Epub 2016 Oct 26 [PubMed PMID: 27816842]

Singh A, Frazee B, Talan DA, Ng V, Perez B. A Tricky Diagnosis. The New England journal of medicine. 2018 Oct 4:379(14):1364-1369. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcps1800926. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30281981]

Heaton D, Huang S, Shiau R, Casillas S, Straily A, Kong LK, Ng V, Petru V. Trichinellosis Outbreak Linked to Consumption of Privately Raised Raw Boar Meat - California, 2017. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2018 Mar 2:67(8):247-249. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6708a3. Epub 2018 Mar 2 [PubMed PMID: 29494570]