Introduction

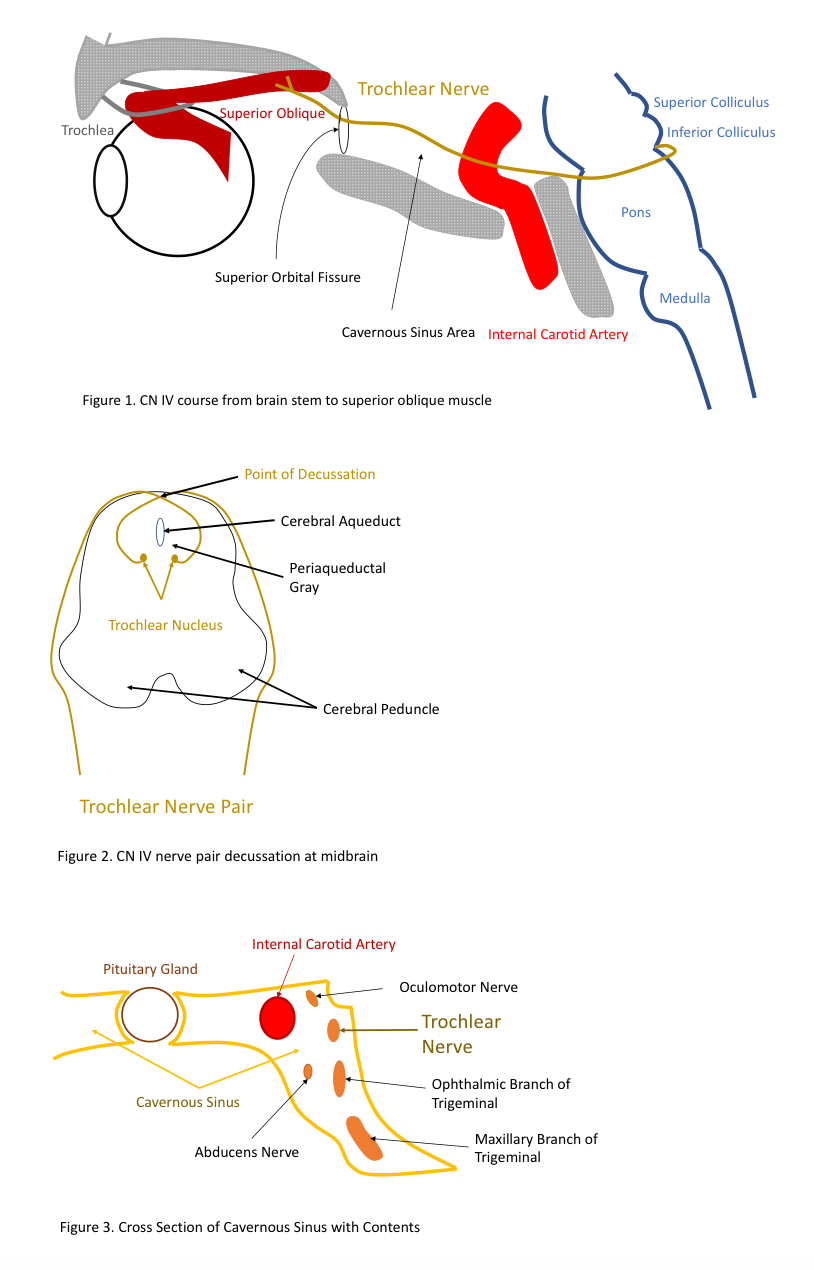

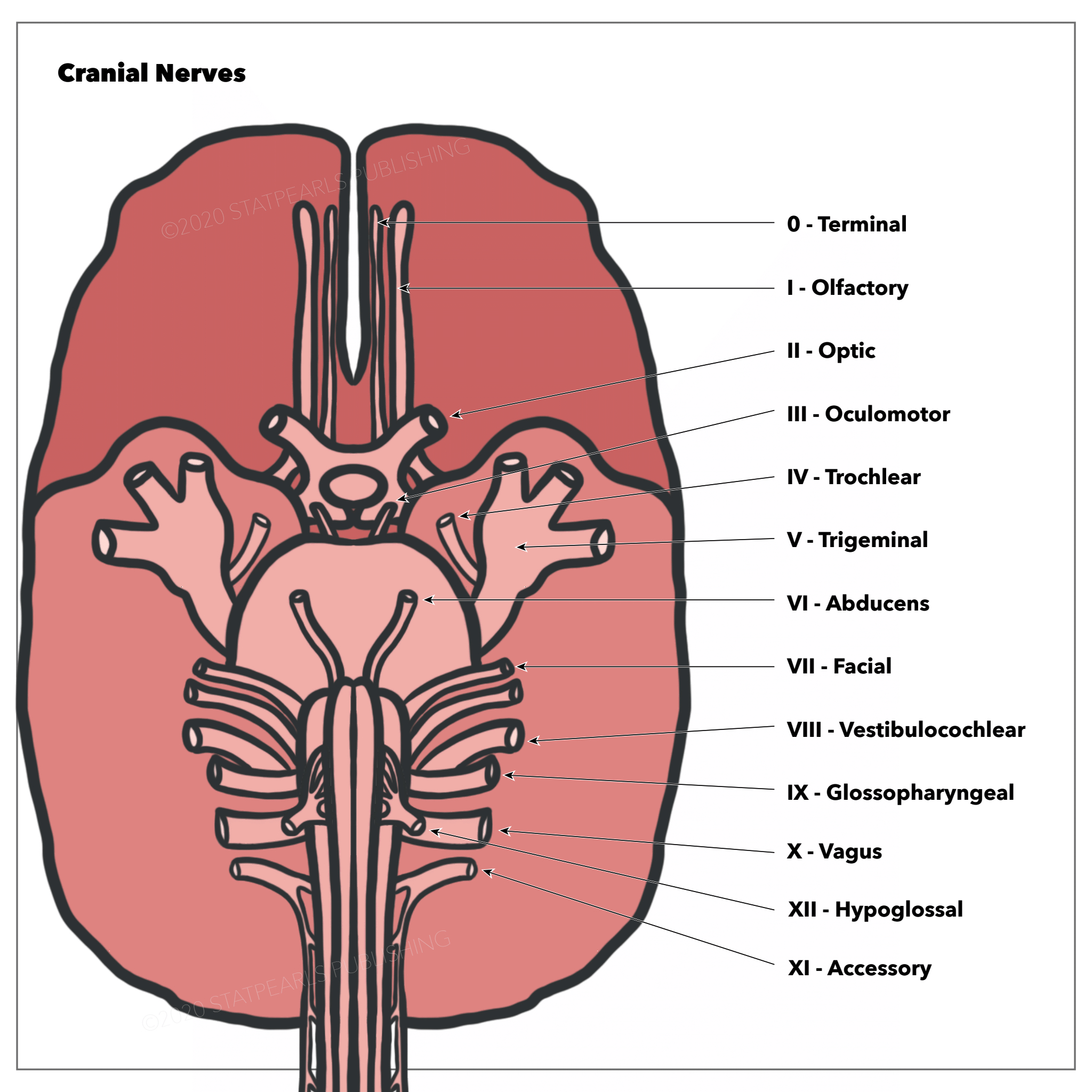

The trochlear nerve is the fourth cranial nerve (CN IV) and one of the ocular motor nerves that controls eye movement. The trochlear nerve, while the smallest of the cranial nerves, has the longest intracranial course as it is the only nerve to have a dorsal exit from the brainstem. It originates in the midbrain and extends laterally and anteriorly to the superior oblique muscle.[1]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

Trochlea is Latin for pulley, which appropriately describes the sling of connective tissue that houses the tendon of the superior oblique. Moreover, the trochlear nerve is a somatic efferent (motor) nerve, and along with oculomotor (III) and abducens (VI) nuclei, it is responsible for eye movement. Through its innervation of the superior oblique, the trochlear nerve controls the abduction and intorsion of the eye.[1]

Embryology

The trochlear nerve, as well as the abducens (VI), hypoglossal (XII), and oculomotor (III) nerves, is a homolog of the ventral roots of the spinal nerves. The somatic efferent columns of the brainstem give rise to these cranial nerves. The muscles that they innervate are derived from the cranial (preoptic and occipital) myotomes in early skeletal muscle development.

During the fourth week of development, the neural tube is composed of three primary vesicles, the prosencephalon, mesencephalon, and rhombencephalon. The mesencephalon goes on to develop into the midbrain. It is from the posterior part of the midbrain that the trochlear nerve originates. From here the nerve passes ventrally to innervate the superior oblique muscle.[2]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The midbrain is supplied by the posterior cerebral artery, superior cerebellar artery, and the basilar artery. As cranial nerve IV has a motor nucleus, it is located near the midline along the medial longitudinal fasciculus. A disruption in any of the aforementioned arterial structures could affect the medial midbrain, and thus, the trochlear nucleus.

Nerves

The trochlear nerve pair originates from a pair of symmetrical trochlear nuclei within the medial midbrain at the level of the inferior colliculus. The left and right nerves then travel dorsally surrounded by the periaqueductal gray matter, decussating before their exit in the dorsal midbrain. The two nerves run on contralateral sides, extend laterally and then anteriorly around the pons, before penetrating the dura above the trigeminal nerve.

It enters the cavernous sinus where it runs anteriorly above the abducens nerve and ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve. Here in the cavernous sinus, a few sympathetic fibers join the trochlear nerve with the possibility of some sensory fibers from the trigeminal nerve. The nerve then enters the orbit through the superior orbital fissure and continues to extend anteriorly to the superior oblique muscle.[1][3] The superior orbital fissure is also the nerve pathway for cranial nerves III, VI, and V and is vulnerable to shearing forces in the setting of trauma.

Muscles

The only muscle the trochlear nerve innervates, the superior oblique muscle, is the longest and thinnest muscle among the extraocular muscles. The muscle belly originates from the back of the roof of the orbit near the common tendinous ring, but it takes an unusual course to reach the eye. The tendon extends between the orbital roof and passes through a fibrous loop (known as the trochlea) located on the frontal bone. The tendon then reaches laterally and posteriorly prior to its insertion point on the posterior half of the eye.

This “pulley” system afforded by the trochlea makes the superior oblique unique among the extraocular muscles and allows for its muscular functions of depression, abduction, and intorsion of the eye. Because of the muscle’s placement at the posterior portion of the eye, the muscle elevates the posterior of the eye, causing the front of the eye to become depressed. The muscle also causes abduction of the eye, moving the pupil away from the nose, and intorsion, rotating the eye such that the top of the eye moves toward the nose.

The superior oblique muscle is the only extraocular muscle that can lower the pupil with the eye adducted. Thus, to isolate the function of the superior oblique muscle from the other extraocular muscles, the muscle can be tested by requesting the patient to adduct the eye and then ask to depress the eye. Failure to depress the eye during adduction indicates a problem with the superior oblique muscle or the trochlear nerve.[4] In addition, a general rule of thumb is that “obliques go opposite”; the left superior oblique is tested by having the patient look right, while the right superior oblique is tested with the patient looking left.

Clinical Significance

The most common cause of an isolated fourth nerve palsy is congenital.[5][6][7][8] These patients may commonly present with eye deviation and complain of diplopia and postural head changes. This characteristic head tilt is towards the unaffected side to compensate for a lack of intorsion from the superior oblique muscle. Congenital trochlear nerve palsies are almost always unilateral. These nerve palsies in children can be initially mistaken for torticollis because of the head tilt many of these children display.[9][10] Most commonly, this can be corrected surgically or with prism. A more conservative approach for minor deviations involves patching of one eye that can alleviate diplopia. However, if patients defer or fail initial therapy, surgical approaches include tucking of the superior oblique tendon or inferior oblique weakening.[11] Interestingly, there is evidence to suggest that congenital superior oblique palsy is more common in young males.[12]

Because of its fragility and extensive intracranial course, the trochlear nerve is especially vulnerable to trauma compared to most cranial nerves. Thus, the most common cause of an acquired defect of the trochlear nerve is trauma.[13] Traumatic trochlear nerve palsies are associated with motor vehicle accidents and boxing, as they involve rapid deceleration of the head. Because the trochlear nerve is so fragile, this can occur in minor head injuries that do not involve loss of consciousness or skull fracture. Shearing forces can result in disruption particularly at the superior orbital fissure, where the trochlear nerve enters the orbit.

Other significant, but less common, causes of fourth nerve palsy include microvascular disease, idiopathic, the mass effect from a tumor, or increased intracranial pressure. Microvascular trochlear nerve palsy usually occurs in the setting of diabetes in patients who are 50 years of age and older.[14] The nerve, however, is less affected compared to the other oculomotor nerves (CN III and CN VI). These nerve injuries are relatively transient with symptom resolution in a few months without treatment. Infrequently, trochlear nerve palsy may be caused by Lyme disease, Meningioma, Guillain-Barre Syndrome, Herpes zoster, and Cavernous Sinus Syndrome.

Another condition that involves the trochlear nerve is superior oblique myokymia which causes spasms of the superior oblique muscle. Symptoms include transient vertical diplopia. The etiology is not known but may be related to other conditions that cause microtremors. Rarely this can cause superior oblique muscle weakness.[9][10]

Lesions of the trochlear nerve can either involve the nucleus or the nerve, but both virtually present with similar symptoms. The only difference is that a unilateral trochlear nuclear lesion affects the contralateral nerve and superior oblique muscle, while a fascicular lesion affects the ipsilateral nerve and muscle. Most trochlear nerve palsies are unilateral. However, because the decussation of the trochlear nerve pair happens when the nerve pair is near each other, a single lesion at the dorsal midbrain can cause bilateral trochlear nerve palsy.[10] If other ocular motor nerves are involved in the patients’ symptoms, a lesion in the cavernous sinus or midbrain is most likely, as these nerves are relatively near each other in this space and share vascular supply.

Clinical presentation of acquired fourth nerve palsy is similar to that of congenital palsy. Patients may present most commonly with diplopia but can also present with blurry vision or a minor vision problem when looking down like reading a book or going down the stairs. The diplopia presented in trochlear nerve palsy is either vertical or diagonal and is worse with a downward gaze. Compensation for the nerve palsy usually includes a head tilt to the opposing side and tucking in the chin, so the affected eye’s pupil can move up and extort, instead of downwards and intort. During clinical examination, the eyes will display hypertropia with the affected eye being slightly elevated relative to the other normal eye. Under cover, the affected eye will show an upward drift relative to the other eye.[15]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Laine FJ. Cranial nerves III, IV, and VI. Topics in magnetic resonance imaging : TMRI. 1996 Apr:8(2):111-30 [PubMed PMID: 8784967]

Cooper ER, THE TROCHLEAR NERVE IN THE HUMAN EMBRYO AND FOETUS. The British journal of ophthalmology. 1947 May [PubMed PMID: 18170343]

Park HK, Rha HK, Lee KJ, Chough CK, Joo W. Microsurgical Anatomy of the Oculomotor Nerve. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2017 Jan:30(1):21-31. doi: 10.1002/ca.22811. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27859787]

Demer JL. Compartmentalization of extraocular muscle function. Eye (London, England). 2015 Feb:29(2):157-62. doi: 10.1038/eye.2014.246. Epub 2014 Oct 24 [PubMed PMID: 25341434]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDosunmu EO, Hatt SR, Leske DA, Hodge DO, Holmes JM. Incidence and Etiology of Presumed Fourth Cranial Nerve Palsy: A Population-based Study. American journal of ophthalmology. 2018 Jan:185():110-114. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2017.10.019. Epub 2017 Nov 2 [PubMed PMID: 29102606]

Brazis PW. Palsies of the trochlear nerve: diagnosis and localization--recent concepts. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 1993 May:68(5):501-9 [PubMed PMID: 8479214]

Miller NR. Pearls and oy-sters: central fourth nerve palsies. Neurology. 2013 Aug 6:81(6):603. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a031ea. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23918863]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHolmes JM, Mutyala S, Maus TL, Grill R, Hodge DO, Gray DT. Pediatric third, fourth, and sixth nerve palsies: a population-based study. American journal of ophthalmology. 1999 Apr:127(4):388-92 [PubMed PMID: 10218690]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAdler FH. Some Physiologic Factors in Differential Diagnosis of Superior Rectus and Superior Oblique Paralysis. Transactions of the American Ophthalmological Society. 1945:43():255-70 [PubMed PMID: 16693380]

Adamec I,Habek M, Superior oblique myokymia. Practical neurology. 2018 Oct [PubMed PMID: 30061333]

Helveston EM, Mora JS, Lipsky SN, Plager DA, Ellis FD, Sprunger DT, Sondhi N. Surgical treatment of superior oblique palsy. Transactions of the American Ophthalmological Society. 1996:94():315-28; discussion 328-34 [PubMed PMID: 8981703]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBagheri A, Fallahi MR, Abrishami M, Salour H, Aletaha M. Clinical features and outcomes of treatment for fourth nerve palsy. Journal of ophthalmic & vision research. 2010 Jan:5(1):27-31 [PubMed PMID: 22737323]

Bixenman WW. Diagnosis of superior oblique palsy. Journal of clinical neuro-ophthalmology. 1981 Sep:1(3):199-208 [PubMed PMID: 6213662]

Tamhankar MA, Biousse V, Ying GS, Prasad S, Subramanian PS, Lee MS, Eggenberger E, Moss HE, Pineles S, Bennett J, Osborne B, Volpe NJ, Liu GT, Bruce BB, Newman NJ, Galetta SL, Balcer LJ. Isolated third, fourth, and sixth cranial nerve palsies from presumed microvascular versus other causes: a prospective study. Ophthalmology. 2013 Nov:120(11):2264-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.04.009. Epub 2013 Jun 6 [PubMed PMID: 23747163]

Brazis PW. Isolated palsies of cranial nerves III, IV, and VI. Seminars in neurology. 2009 Feb:29(1):14-28. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1124019. Epub 2009 Feb 12 [PubMed PMID: 19214929]