Introduction

Tympanic membrane perforation is when the tympanic membrane (TM) ruptures, creating a hole between the external and middle ear. The TM is a layer of cartilaginous connective tissue, with skin on the outer surface and mucosa covering the inner surface that separates the external auditory canal from the middle ear and ossicles. The TM function is to aid in hearing by creating vibrations whenever struck by sound waves and transmitting those vibrations to the inner ear.[1] When the tympanic membrane perforates, it may no longer create the vibrational patterns, leading to hearing loss in some instances.

Tympanic membrane rupture can occur at any age, although it is mainly seen in the younger population, associated with acute otitis media. As a patient's age increases, trauma becomes a more likely cause of TM rupture. Men are more likely to experience TM perforation compared to women.

Signs and symptoms of tympanic membrane perforation are the same despite the cause of the rupture. There is often sudden onset of pain, followed by relief, with associated otorrhea. Tinnitus and vertiginous symptoms may also be experienced.

Overall, TM perforation has a favorable prognosis with a small risk of complications. Perforations tend to heal spontaneously without intervention. It is important to know when intervention and early referral is required, based on size, location, and symptoms associated with the perforation.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

TM perforations have multiple origins such as a complication of infection (acute otitis media or otitis externa secondary to Aspergillus niger), barotrauma from explosions, scuba diving, or air travel, sudden negative pressure, head trauma, noise trauma, insertion of objects into the ear, or iatrogenic from attempting foreign body or cerumen removal. With acute otitis media (AOM), the risk of spontaneous perforation increases with recurrent episodes of AOM and AOM caused by non-typeable Hemophilus influenzae.[2] Most commonly, perforations are caused by trauma or AOM.[3] Rarely, it has also been seen as secondary to lightning strikes.[4] There are risk factors for TM rupture, as well, such as prior ear surgeries, severe otitis externa, and prior or current otitis media.

Epidemiology

While TM perforation incidence is unknown overall, given that many heal spontaneously, it is not uncommon to see a ruptured tympanic membrane in clinical practice. One study of nearly 1,000 patients in the United States showed that men more commonly had traumatic rupture compared to women in a ratio of 1.49:1.[5] A study out of Nigeria looking at 529 patients found similar statistics to the United States with a male to female ratio of 2:1.[6] Another study with 80 participants showed that the average age of patients who experience TM perforation was 26.7 +/- 14.6 years, with children making up 25% of the sample size.[7]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology behind TM rupture depends on the etiology of the rupture itself. For instance, perforation secondary to barotrauma is related to large or rapid changes in pressure gradients between the middle and external ear. For example, with scuba diving, the pressure in the middle ear is unequal to the pressure in the external auditory canal, creating an air squeeze. The difference across the membrane can ultimately lead to eardrum rupture.

Perforation from a foreign body (FB) or ear cleaning is from direct penetration to the eardrum itself, usually in the area of the pars tensa. The pars tensa is the largest and thinnest area of the TM, only a few cell layers thick, located in the inferior and anterior region of the eardrum. Therefore, it is the most commonly and easily torn area, especially secondary to blunt and noise trauma.[1]

Otitis media causes necrosis and ischemia of the TM leading breakdown and rupture. The most common region for rupture is in the central membrane, followed by the anterior central and posterior central regions, correlating to the pars tensa being most frequently injured, as noted above.[6]

History and Physical

Patients experiencing tympanic membrane perforation usually complain of sudden onset of pain accompanied by hearing loss, bloody otorrhea, hearing loss, vertigo, or tinnitus. In the study from Nigeria, the most common presenting symptom was otorrhea (81.5%), followed by otalgia (72.8%) and tinnitus (55.7%).[6] Unless there is associated inner ear injury, vertigo and tinnitus are typically fleeting. The physical exam must include otoscopy for direct visualization and a general assessment of vestibular function and hearing.[8] A thorough neurologic examination is required, as well, to rule out neurologic causes of tinnitus, hearing loss, and vertigo.

Evaluation

Tympanic membrane rupture is a clinical diagnosis. In the absence of obvious TM rupture on exam, pneumatic otoscopy and tympanometry can be used to assess for occult perforation. However, these devices are not always readily available. Additionally, if perforation is suspected, pneumatic otoscopy should generally be avoided for the risk of damage to the middle ear. Otoscope fogging may also be used as an indicator for perforation, as warm humidified air is connecting from the nasopharynx into the middle ear and communicating to the EAC via the perforation, leading to condensation on the otoscope.[9] Definitive diagnosis for occult TM rupture would require otomicroscopy or middle ear impedance studies, performed on an outpatient basis.[10]

Treatment / Management

Treatment is primarily supportive, as TM perforations generally heal spontaneously. The ear should be kept dry as much as possible since it can predispose to infection if the ear is wet.[11] One prospective study of traumatic perforation demonstrated that the use of ofloxacin otic drops improved rate and time to closure of the perforation compared to those not treated. However, it was also found that ofloxacin drops made no change in hearing outcomes or the rate of AOM secondary to large perforations.[12] Routine antibiotic treatment is often unnecessary. If perforations are located in the posterosuperior quadrant, caused by penetrating trauma, or has been present for less than two months, surgery would be indicated, and the patient should be referred to otolaryngology, as these are associated with poor routine healing.[13] Moreover, if hearing loss is present, patients should be referred to otolaryngology and audiology early on.

Differential Diagnosis

Tympanic membrane rupture is generally easy to identify based on history and physical exam alone. However, there is other pathology that needs to be considered when assessing for TM perforation. Differential diagnosis includes AOM, otitis externa, traumatic otorrhea (CSF otorrhea), brain or inner ear neoplasm, posterior stroke, Ramsay Hunt syndrome, ear FB, auricular hematoma, bullous myringitis, labyrinthitis, cholesteatoma, and perilymphatic fistula, to name a few. A thorough history and physical exam can help narrow down the diagnosis.

Prognosis

The prognosis for TM perforation is excellent overall. As mentioned above, tympanic membrane perforations typically heal on their own, leading to a favorable prognosis. Studies have shown small TM ruptures have a high likelihood of spontaneous closure over a three to four week period.[14] Another study found there is a 90% rate of closure over a 6 week period.[10] The leading causes of delayed or non-closure are the size of the perforation and secondary infection.[15] Of those who experience delayed closure, chronic perforations, or other complications, surgery is generally indicated. Patients may experience reperforation after surgical repair in anywhere from 7% to 27% of cases. It was determined that the primary factor affecting the outcome was clinical skill alone [16]. Therefore, follow up for many years after surgical intervention is warranted to monitor for delayed complications. Morbidity is related primarily to associated hearing loss in untreated TM perforations, which would benefit from repair. Despite this, overall mortality and morbidity remain low for TM perforations.

Complications

Patients who experience a perforated TM may develop chronic otitis media. If chronic otitis develops, the infection can erode into the ossicles of the inner ear affecting hearing.[3] Ultimately, the patient can develop permanent sensorineural hearing loss. In one study with 529 patients, the most commonly seen complication was hearing loss, which occurred in 52.6% of patients. Of those cases, most involved only mild to moderate hearing loss.[6] Furthermore, chronic infection can create facial nerve paralysis by affecting CN VII in the middle ear or spread to the brain leading to meningitis or brain abscess. Mastoiditis can also occur from chronic otitis media secondary to chronic perforation. Cholesteatomas can also form, ultimately destroying the middle ear bones over time or eroding into the inner ear and lead to permanent hearing loss and vertigo. Almost all of these patients require surgery and should have a prompt evaluation by an otolaryngologist.[13]

Deterrence and Patient Education

As tympanic membrane rupture is generally unintentional, prevention tactics are limited. However, patients should always be instructed not to use cotton tip swabs in an attempt to clean the ear, as this can cause direct trauma and perforation. One study discovered that of 949 patients with TM perforation, 261 were caused by the use of cotton tip applicators for cleaning their ear canal.[5] Strict instructions should be provided against the use of cotton tip swabs for the prevention of TM rupture. Once the patient is found to have a tympanic membrane rupture, the most important take-home instruction is to keep the ear dry.[17] If water enters the ear, it can be a nidus for AOM, causing increased complications.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Patients with tympanic membrane rupture are typically initially seen by their primary care provider or in the emergency department setting. For the patients who have large perforations, posterior location of the injury, hearing loss, or other severe symptoms, the patient would benefit from referral to an otolaryngologist for an interdisciplinary approach to patient care. Ultimately, timely diagnosis and referral help to improve long term outcomes and decreased overall morbidity.

Media

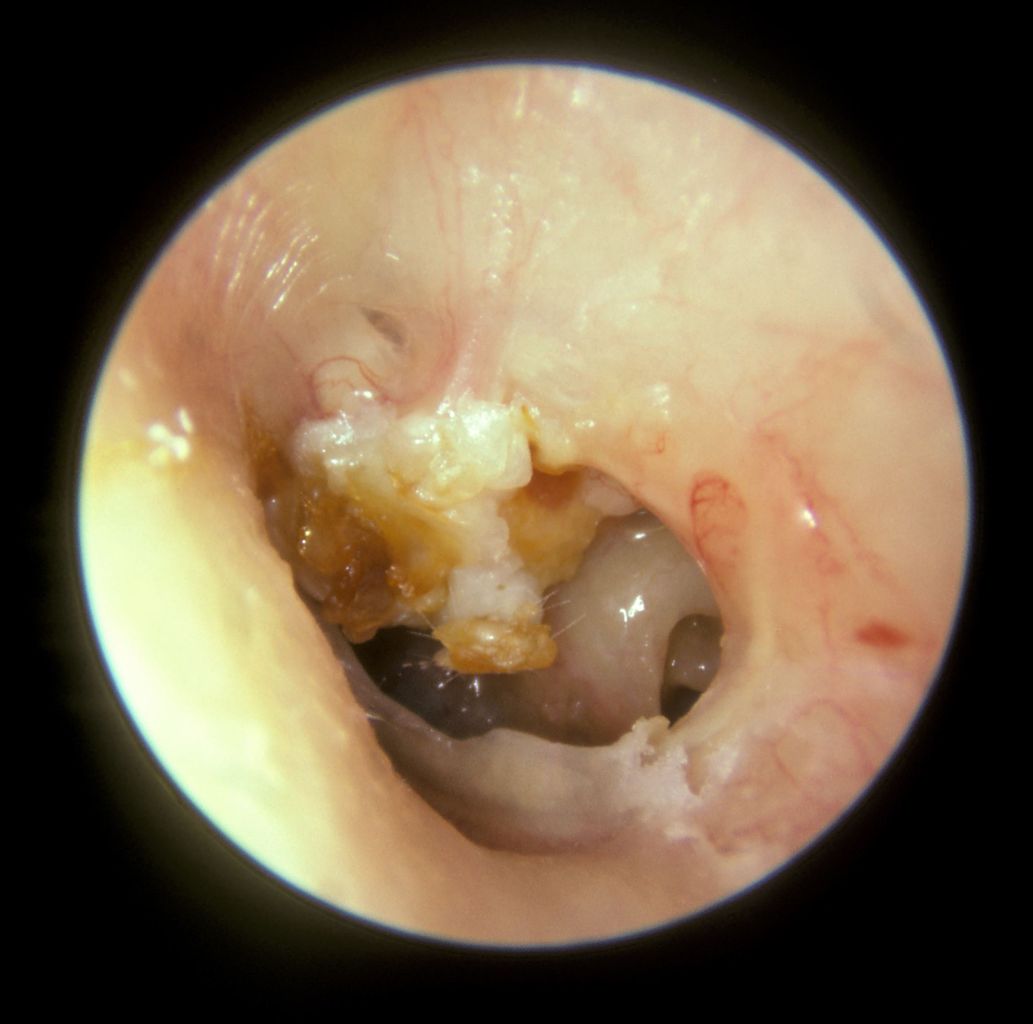

(Click Image to Enlarge)

The large mass of white keratin debris in the left upper quadrant of this left tympanic membrane is a cholesteatoma. The majority of the tympanic membrane is missing [perforation]. In the lower right quadrant the round window niche on the medial wall middleware can be seen. Contributed by Wikimedia Commons, Michael Hawke MD (CC by 4.0) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

References

Lim DJ. Structure and function of the tympanic membrane: a review. Acta oto-rhino-laryngologica Belgica. 1995:49(2):101-15 [PubMed PMID: 7610903]

Marchisio P, Esposito S, Picca M, Baggi E, Terranova L, Orenti A, Biganzoli E, Principi N, Milan AOM Study Group. Prospective evaluation of the aetiology of acute otitis media with spontaneous tympanic membrane perforation. Clinical microbiology and infection : the official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 2017 Jul:23(7):486.e1-486.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2017.01.010. Epub 2017 Jan 19 [PubMed PMID: 28110050]

Pannu KK, Chadha S, Kumar D, Preeti. Evaluation of hearing loss in tympanic membrane perforation. Indian journal of otolaryngology and head and neck surgery : official publication of the Association of Otolaryngologists of India. 2011 Jul:63(3):208-13. doi: 10.1007/s12070-011-0129-6. Epub 2011 Feb 23 [PubMed PMID: 22754796]

Bozan N, Kiroglu AF, Ari M, Turan M, Cankaya H. Tympanic Membrane Perforation Caused by Thunderbolt Strike. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2016 Nov:27(8):e723-e724. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000003036. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28005796]

Carniol ET, Bresler A, Shaigany K, Svider P, Baredes S, Eloy JA, Ying YM. Traumatic Tympanic Membrane Perforations Diagnosed in Emergency Departments. JAMA otolaryngology-- head & neck surgery. 2018 Feb 1:144(2):136-139. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2017.2550. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29270620]

Adegbiji WA, Olajide GT, Olajuyin OA, Olatoke F, Nwawolo CC. Pattern of tympanic membrane perforation in a tertiary hospital in Nigeria. Nigerian journal of clinical practice. 2018 Aug:21(8):1044-1049. doi: 10.4103/njcp.njcp_380_17. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30074009]

Sagiv D, Migirov L, Glikson E, Mansour J, Yousovich R, Wolf M, Shapira Y. Traumatic Perforation of the Tympanic Membrane: A Review of 80 Cases. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2018 Feb:54(2):186-190. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2017.09.018. Epub 2017 Oct 28 [PubMed PMID: 29110975]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVan Hoecke H, Calus L, Dhooge I. Middle ear damages. B-ENT. 2016:Suppl 26(1):173-183 [PubMed PMID: 29461741]

Naylor JF. Otoscope fogging: examination finding for perforated tympanic membrane. BMJ case reports. 2014 May 30:2014():. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-200707. Epub 2014 May 30 [PubMed PMID: 24879720]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChen F, Yang XP, Liu X, Dong DA, Zhou XR, Fan LH. Retrospective Analysis of 24 Cases of Forensic Medical Identification on Traumatic Tympanic Membrane Perforations. Fa yi xue za zhi. 2018 Aug:34(4):392-395. doi: 10.12116/j.issn.1004-5619.2018.04.010. Epub 2018 Aug 25 [PubMed PMID: 30465405]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSinkkonen ST, Jero J, Aarnisalo AA. [Tympanic membrane perforation ]. Duodecim; laaketieteellinen aikakauskirja. 2014:130(8):810-8 [PubMed PMID: 24822331]

Lou Z, Lou Z, Tang Y, Xiao J. The effect of ofloxacin otic drops on the regeneration of human traumatic tympanic membrane perforations. Clinical otolaryngology : official journal of ENT-UK ; official journal of Netherlands Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology & Cervico-Facial Surgery. 2016 Oct:41(5):564-70. doi: 10.1111/coa.12564. Epub 2016 Feb 11 [PubMed PMID: 26463556]

Sogebi OA, Oyewole EA, Mabifah TO. Traumatic tympanic membrane perforations: characteristics and factors affecting outcome. Ghana medical journal. 2018 Mar:52(1):34-40. doi: 10.4314/gmj.v52i1.7. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30013259]

Jellinge ME, Kristensen S, Larsen K. Spontaneous closure of traumatic tympanic membrane perforations: observational study. The Journal of laryngology and otology. 2015 Oct:129(10):950-4. doi: 10.1017/S0022215115002303. Epub 2015 Sep 7 [PubMed PMID: 26344019]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAfolabi OA, Aremu SK, Alabi BS, Segun-Busari S. Traumatic tympanic membrane perforation: an aetiological profile. BMC research notes. 2009 Nov 21:2():232. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-2-232. Epub 2009 Nov 21 [PubMed PMID: 19930586]

Albera R, Ferrero V, Lacilla M, Canale A. Tympanic reperforation in myringoplasty: evaluation of prognostic factors. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 2006 Dec:115(12):875-9 [PubMed PMID: 17214259]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKraus F, Hagen R. [The Traumatic Tympanic Membrane Perforation - Aetiology and Therapy]. Laryngo- rhino- otologie. 2015 Sep:94(9):596-600. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1395522. Epub 2015 Jan 7 [PubMed PMID: 25565334]