Introduction

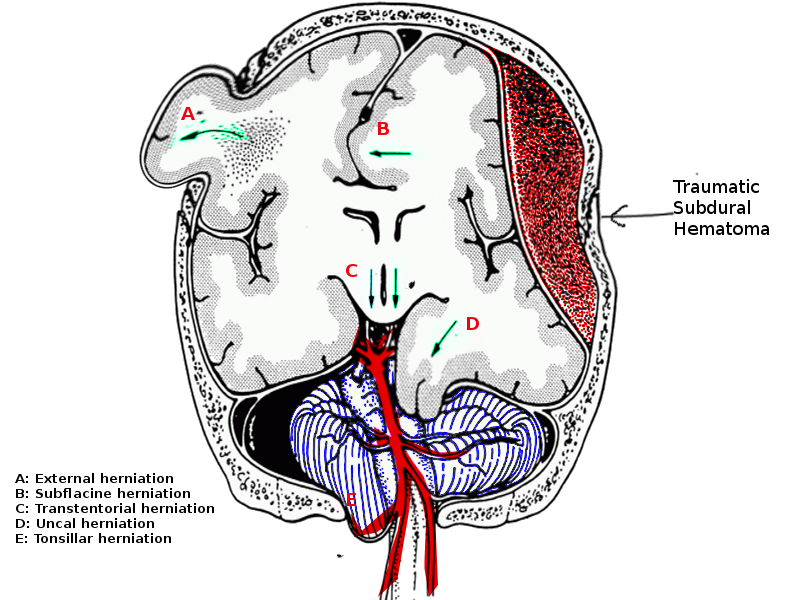

The uncus is a structure at the anterior medial aspect of the parahippocampal gyrus in the medial temporal region of the brain. The medial temporal region is within the supratentorial compartment of the cranium connected to the subtentorial compartment via the tentorium cerebelli through the tentorial notch. The structures in the tentorial notch include the midbrain, third cranial nerve, posterior cerebral arteries, and superior cerebellar arteries. The cerebellum occupies the posterior portion of the tentorial notch. Uncal herniation occurs when rising intracranial pressure causes portions of the brain to flow from one intracranial compartment to another; this is a life-threatening neurological emergency and indicates the failure of all adaptive mechanisms for intracranial compliance.[1]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

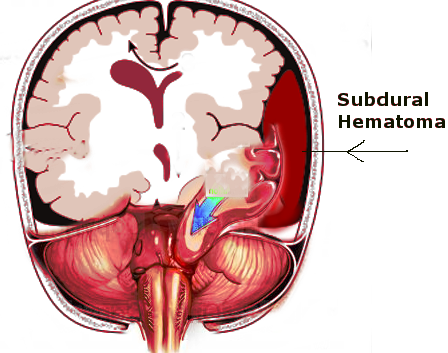

The causes of uncal herniation include any situations which will cause a significant rise in intracranial pressure. Any expanding space-occupying lesion within the cranium can subject a patient to be at risk for uncal herniation. Uncal herniation can occur following severe head trauma which may lead to a rapidly expanding subdural or epidural hematoma. In uncal herniation, there is usually some supratentorial driving force occurring with a raised intracranial pressure (ICP) causing the uncus to slide over the supratentorial notch.[2]

Epidemiology

The actual incidence of uncal herniation is poorly understood. Since uncal herniation can occur secondary to traumatic brain injury, it is essential to understand the occurrence of traumatic brain injury (TBI) to highlight an at-risk population. According to the CDC's 2015 Report to Congress on Traumatic Brain Injury, there are approximately 30 million injury-associated emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and deaths every year in the United States. TBI accounts for 16% of injury-related hospitalizations and one-third of injury-related deaths. Specifically, in 2010, the centers for disease control and prevention (CDC) estimated that TBIs accounted for about 2.5 million emergency department (ED) visits, hospitalizations, and deaths in the United States, either isolated or in combination with other injuries.

Pathophysiology

The three components which make up the intracranial compartment are brain tissue, arterial or venous blood, and cerebrospinal fluid. According to the Monro-Kellie principle, any increase in one of these components will come at the expense of another component.[3][4] For example, a mass present in the supratentorial compartment will reduce cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and venous blood volume first, followed by reductions in arterial blood flow and volume and herniation of brain tissue through existing cranial openings.[3] The uncus herniates over the tentorial notch and pushes against the brainstem and corresponding cranial nerves, compressing the third cranial nerve located just medial to the uncus.

History and Physical

A patient with impending uncal herniation will initially present with symptoms of increased intracranial pressure. These symptoms include headache, nausea, vomiting, and altered mental status. Physical exam in increased ICP will reveal Cushing's triad of hypertension, bradycardia, and irregular respiration or apnea.[1] A late finding on an ophthalmologic exam in a patient with increased ICP is papilledema, which presents with a blurring of the optic disc margin and decreased venous pulsations. The cardinal signs of uncal herniation are an acute loss of consciousness associated with ipsilateral pupillary dilation and contralateral hemiparesis. These symptoms are due to compression or displacement of ascending arousal pathways, the oculomotor nerve (CN III), and the corticospinal tract.[1] The hallmark unilateral dilated pupil can be the first symptom to appear without severe impairment in the level of consciousness or contralateral hemiparesis. In patients who present with isolated anisocoria, this could be a sign that there is impending uncal herniation.[5] Over time, the patient may develop impaired ocular motility which will give the eye a classic down-and-out appearance. Further compression of the midbrain due to uncal herniation can then progress to lethargy, coma, or death. Ultimately if untreated, uncal herniation progresses to central herniation.

Evaluation

Uncal herniation diagnosis is by its characteristic physical exam findings and confirmed with brain imaging. Any patient who presents with Cushing's triad warrants an immediate computed tomogram (CT) scan to rule out life-threatening hemorrhage, herniation, or mass lesion.[6] A cranial CT scan is the preferred imaging technique over magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in the emergent setting; it can be completed quickly, and CT imaging technology is more available.[1]

Treatment / Management

When the signs of uncal herniation are present, the physician must act rapidly to reduce intracranial pressure by adjusting the volume of one component of the intracranial compartment, either brain, blood, or cerebrospinal fluid.[4] Management strategies to achieve this include:

- Elevating the head of the bed thirty degrees

- Keeping the head midline

- Hyperventilation

- Hyperosmolar therapy with either mannitol or hypertonic saline

Hyperventilation works to reduce the intracranial pressure by decreasing arterial carbon dioxide levels which will induce vasoconstriction to reduce the cerebral blood volume; this is achievable by increasing tidal volume or respiratory rate with a target PaCO2 of 30-35 mmHg. Hyperventilation is typically reserved for situations where there is life-threatening intracranial hypertension, such as in uncal herniation.[3][7][3](A1)

Hyperosmolar therapy with mannitol or 3% hypertonic saline is administered to patients with intracranial pressure elevations above 20 mmHg or when there is suspected brain herniation. Mannitol is given as a bolus dose of 0.5-1 g/kg and can be administered every four hours as needed for intracranial pressures above 20 mmHg, maintaining the osmolar gap less than 20 mOsm. 3% hypertonic saline is given as a bolus dose of 5-10 mL/kg in patients with acute elevations of intracranial pressure or with signs of brain herniation. Hypertonic saline can be administered as a continuous infusion at 0.5-1.5 mL/kg/hr.[1][8][1]

The next step for the management of uncal herniation if clinical signs do not resolve with interventions to reduce intracranial pressure is to consider decompressive surgical options.[1] These include:

- Placement of a ventricular drain

- Evacuation of an extra-axial lesion such as epidural hematoma

- Resection of an intracerebral lesion

- Removal of brain parenchyma

- Uni- or bilateral craniectomies

Differential Diagnosis

Since uncal herniation occurs after a significant elevation in intracranial pressure, the differential diagnosis would include any conditions with symptoms of a headache, nausea, vomiting, or altered mental status. Some possible differentials for uncal herniation could include:

- Diabetic ketoacidosis

- Encephalitis

- Intracranial hemorrhage

- Ischemic stroke

- Meningitis

- Neoplasm

- Sepsis

- Subdural/epidural hematoma

- Systemic lupus erythematosus

- TBI/concussion syndrome

- Toxins exposure

Prognosis

An important factor for a better neurosurgical outcome in patients with uncal herniation is early diagnosis and timely management of the condition.[5] The degree of herniation will also affect the prognosis of patients with uncal herniation. The reversibility of the herniation becomes more difficult in patients with multiple traumas or when new complications arise as herniation increases. Reversal of uncal herniation can be achieved, however, if the interventions commence rapidly.[9] Reversal of uncal herniation is known to occur in 50–75% of adult patients with either traumatic brain injury or with supratentorial mass lesions.[1] Long-term outcomes after successful treatment for herniation may be more favorable in children than in adults.[1]

Complications

The most severe complications seen in uncal herniation are coma or death due to the failure of management strategies to reverse the herniation syndrome. Depending on the amount of tissue involved in the herniation, the patient is also at risk for the development of brainstem or cortical ischemia because of the anatomical proximity of major blood vessels. There are few cases of a rare complication of chronic uncal herniation seen mostly in children with Dandy-Walker syndrome or other cystic cavities in communication with the fourth ventricle because of posterior fossa shunting.[2][10][2]

Consultations

A team familiar with the signs and symptoms of herniation syndromes should monitor patients presenting with TBI. The neurosurgeons, neuro-intensivists, and support staff with experience caring for patients with significant neuro injury will be crucial members of the team.

Deterrence and Patient Education

The best deterrence and prevention is appropriate precautions when operating motor vehicles or using firearms as these are common causes of traumatic brain injury. Most medical causes of space-occupying brain lesions are difficult if not impossible to prevent.

Pearls and Other Issues

- Uncal herniation occurs because of a lesion that overwhelms the ability of the three components in the cranium to compensate for pressure increases.

- The cardinal signs of uncal herniation are an acute loss of consciousness associated with ipsilateral pupillary dilation and contralateral hemiparesis.

- Anisocoria is a cause for concern, and its cause should be sought.

- CT scan is the preferred imaging technique over magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in the emergent setting as it can be completed quickly and CT imaging technology is more available

- Uncal herniation can is reversible if recognized early and treated aggressively.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Neurological resuscitation is a true team sport requiring close communication between disciplines. Nurses are the ultimate patient monitors and recognition of subtle changes may make the difference in outcomes. Respiratory therapists, like nurses, should be keenly attuned to subtle changes in the patient's respiratory status as changes in pulmonary compliance may affect ICP by increasing venous pressure and increasing PCO2. Care will require a team of physicians and their ability to communicate freely will be essential to improving outcomes. All members of the team should be empowered to contribute freely and encouraged to report subtle changes that can affect the patient's outcome. The most effective teams will find a method of discussing the patient's care at least twice and developing a plan that addresses the patient's needs.

Media

References

Cadena R, Shoykhet M, Ratcliff JJ. Emergency Neurological Life Support: Intracranial Hypertension and Herniation. Neurocritical care. 2017 Sep:27(Suppl 1):82-88. doi: 10.1007/s12028-017-0454-z. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28913634]

Udayakumaran S, Ben Sira L, Constantini S. Chronic uncal herniation secondary to posterior fossa shunting: case report and literature review. Child's nervous system : ChNS : official journal of the International Society for Pediatric Neurosurgery. 2010 Feb:26(2):267-71. doi: 10.1007/s00381-009-1027-z. Epub 2009 Nov 14 [PubMed PMID: 19915852]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGodoy DA, Lubillo S, Rabinstein AA. Pathophysiology and Management of Intracranial Hypertension and Tissular Brain Hypoxia After Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: An Integrative Approach. Neurosurgery clinics of North America. 2018 Apr:29(2):195-212. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2017.12.001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29502711]

Mokri B. The Monro-Kellie hypothesis: applications in CSF volume depletion. Neurology. 2001 Jun 26:56(12):1746-8 [PubMed PMID: 11425944]

Munakomi S, Mohan Kumar B. Case Report: Frontalis sign for early bedside consideration of impending uncal herniation. F1000Research. 2016:5():125. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.7871.2. Epub 2016 Feb 1 [PubMed PMID: 27635220]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSchimpf MM. Diagnosing increased intracranial pressure. Journal of trauma nursing : the official journal of the Society of Trauma Nurses. 2012 Jul-Sep:19(3):160-7. doi: 10.1097/JTN.0b013e318261cfb4. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22955712]

Procaccio F,Stocchetti N,Citerio G,Berardino M,Beretta L,Della Corte F,D'Avella D,Brambilla GL,Delfini R,Servadei F,Tomei G, Guidelines for the treatment of adults with severe head trauma (part I). Initial assessment; evaluation and pre-hospital treatment; current criteria for hospital admission; systemic and cerebral monitoring. Journal of neurosurgical sciences. 2000 Mar; [PubMed PMID: 10961490]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceOng C, Hutch M, Barra M, Kim A, Zafar S, Smirnakis S. Effects of Osmotic Therapy on Pupil Reactivity: Quantification Using Pupillometry in Critically Ill Neurologic Patients. Neurocritical care. 2019 Apr:30(2):307-315. doi: 10.1007/s12028-018-0620-y. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30298336]

Uzan M, Yentür E, Hanci M, Kaynar MY, Kafadar A, Sarioglu AC, Bahar M, Kuday C. Is it possible to recover from uncal herniation? Analysis of 71 head injured cases. Journal of neurosurgical sciences. 1998 Jun:42(2):89-94 [PubMed PMID: 9826793]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWijdicks EF. Neurological picture. Acute brainstem displacement without uncal herniation and posterior cerebral artery injury. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 2008 Jul:79(7):744. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.126227. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18559458]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence