Introduction

Regional anesthesia, particularly the use of peripheral nerve blocks, allows for localized, targeted anesthesia for surgical anesthesia and an adjunct to general anesthesia for postoperative pain control. Systemic, generalized adverse effects can be avoided by focusing on a specific anatomical location. Performing a targeted peripheral nerve block can also be a significant part of a multimodal analgesic approach to reduce opioid use.

The provider must have the appropriate equipment and a targeted nerve structure to perform a peripheral nerve block. When choosing a local anesthetic for a true surgical block, surgical duration should be considered. Literature has shown that one of the most critical factors of a successful peripheral nerve block is the mass or total dosage of the local anesthetic. Multiple adjuncts can be combined with local anesthetics to decrease the onset time, increase the duration, and increase the quality and density of the block.[1]

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

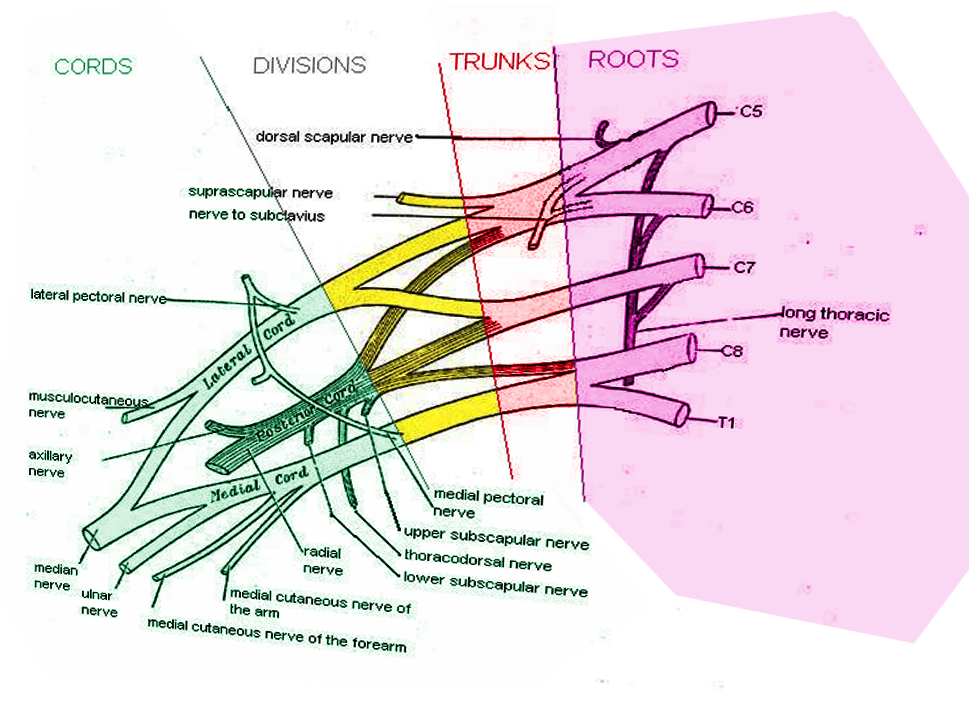

Knowledge of the brachial plexus anatomy is critical in choosing and administering an effective upper extremity anesthetic block.

The brachial plexus is derived from the C5 to T1 nerve roots. The nerve roots exit their respective intervertebral foramina, travel between the anterior and middle scalene muscles, and begin to form the brachial plexus. At the most proximal portion of the brachial plexus, the nerve roots form three trunks: the upper, middle, and lower trunks. The 3 trunks pass over the first rib, forming 2 divisions as they pass under the clavicle: the anterior and posterior divisions. Distal to the clavicle, the divisions form 3 cords: the lateral, posterior, and medial cords. Each cord gives off a branch and ultimately becomes a terminal nerve.

Choosing a regional upper limb block requires consideration of the targeted anatomy. The roots, trunks, divisions, cords, and branches require an interscalene, supraclavicular, infraclavicular, or axillary block, respectively. Particular cutaneous portions of the upper extremity may need additional, separate blocks; for example, the anterior shoulder, which has contributions from the superficial plexus (C1 to C4).[2][3]

Indications

The general indications for upper extremity peripheral nerve blocks are surgical anesthesia and postoperative pain management for surgeries involving the upper arm or forearm. In addition, each upper extremity block has its indications based on the location of the surgery.

The interscalene nerve block is typically indicated for shoulder surgery but is insufficient for surgeries distal to the elbow. The supraclavicular nerve block is particularly useful as it encompasses the entire arm. The infraclavicular and axillary nerve blocks are indicated for surgeries involving the elbow and distal to the elbow, respectively.

When properly performed, none of the brachial plexus blocks will cover the upper medial portion of the upper extremity proximal to the elbow. To block this region, an intercostobrachial nerve block must be performed as an adjunct to a brachial plexus block.[4][5]

Contraindications

Contraindications to peripheral nerve blocks include patient refusal or inability to provide consent, coagulopathy or anticoagulation use, ongoing infection, and abnormal anatomy obscuring the trajectory of the needle, which makes it difficult or nearly impossible to target the appropriate structures.

Technique or Treatment

The following are the brachial plexus blocks in proximal to distal anatomical order of the brachial plexus: interscalene, supraclavicular, infraclavicular, and axillary.

Interscalene Nerve Block

The interscalene nerve block targets the C5, C6, and C7 nerve roots at the root level and is indicated for upper arm surgeries involving the shoulder. The interscalene block spares the ulnar nerve distribution; it should not be used for surgical anesthesia in forearm or wrist procedures.

Position the patient's head turned away from the side of interest. Next, palpate the interscalene groove at the lateral edge of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. With ultrasound guidance, the 3 nerve roots can be appreciated as three distinct hypoechoic circular structures between the scalene muscles. Ensure all appropriate equipment and needles are ready at the bedside. Finally, cleanse the patient’s neck in a sterile fashion.

A suitable needle should be advanced in-plane, aiming between the C5 and C6 nerve root. A distinct pop should be felt as the needle traverses the fascia encompassing the nerve roots. Confirm the desired position using ultrasound and apply negative aspiration before injecting the desired volume of local anesthetic.

A properly performed interscalene nerve block almost always results in some degree of ipsilateral phrenic nerve paralysis. For this reason, practitioners should avoid or consider risks versus benefits for patients with an underlying respiratory disease, such as advanced COPD. Another potential complication of the interscalene nerve block is Horner syndrome, a triad of ptosis, miosis, and anhidrosis.[4][5]

Supraclavicular Nerve Block

The supraclavicular nerve block targets the trunks and divisions of the brachial plexus. This nerve block provides anesthesia for most of the arm excluding the upper medial portion proximal to the elbow.

Position the patient's head turned away from the side of interest. Obtain a circular view of the subclavian artery with ultrasound guidance by placing the ultrasound probe parallel to the clavicle. The brachial plexus, found lateral and superior to the subclavian artery, appears as either three hypoechoic circles resembling a “stoplight” when more proximal (representing the trunks of the brachial plexus) or as a cluster of 5 to 6 smaller hypoechoic circles (representing the divisions of the brachial plexus).

A suitable needle should be advanced to target these structures. Confirm the desired position using ultrasound and apply negative aspiration before injecting the desired volume of local anesthetic. If injected in the correct position, the local anesthetic should spread circumferentially around the nerve bundle, giving the bundle a floating appearance.

Phrenic nerve paralysis and Horner syndrome may complicate a supraclavicular nerve block but occur less commonly than with an interscalene nerve block. However, pneumothorax occurs more frequently with a supraclavicular nerve black than an interscalene nerve block.[6]

Infraclavicular Nerve Block

The infraclavicular nerve block targets the divisions and cords of the brachial plexus and provides anesthesia for the hand, forearm, elbow, and lateral upper arm. Unfortunately, it is more difficult to visualize the target structures with this approach; this has caused the infraclavicular nerve block to fall out of favor for most practitioners.

Position the patient's head turned away from the side of interest. Obtain a circular view of the subclavian artery with ultrasound guidance by placing the ultrasound probe inferior and perpendicular to the clavicle. Place a suitable needle almost adjacent to the clavicle, superior to the short end of the ultrasound probe. Direct the needle at the inferior border of the subclavian artery. Confirm the desired position using ultrasound, and apply negative aspiration before injecting the desired volume of local anesthetic. The local anesthetic should spread to the nerves around the subclavian artery and provide a sufficient nerve block.

Complications of the infraclavicular nerve block are pneumothorax, hemothorax, intravascular injection of local anesthetic, trauma to surrounding tissues, and chylothorax if performed on the left side.[6]

Axillary Nerve Block

The axillary nerve block is performed at the level of the branches of the brachial plexus and is most useful for procedures involving the forearm. Place the ultrasound probe in the patient's axilla to locate the axillary artery in a cross-sectional view, appearing as a circle. The target nerves surrounding the artery are the radial, median, and ulnar nerves. A suitable needle should be advanced to target these structures. Confirm the desired position using ultrasound, and apply negative aspiration before injecting the desired volume of local anesthetic.

To obtain a complete block distal to the elbow, the musculocutaneous nerve, located in the belly of the coracobrachialis muscle, must be targeted as well.

Complications

Complications of peripheral nerve blocks are rare. There is always a risk that a peripheral nerve block will be unsuccessful. Certain complications are more common in certain anatomical locations (see techniques above). Known complications of peripheral nerve blocks include the following:

- Nerve root injury

- Paresthesias

- Intrathecal or epidural injection of the anesthetic agent

- Traumatic injury to surrounding structures, including blood vessels and musculature

- Pneumothorax

- Infection with or without abscess formation

- Local anesthetic toxicity, with central nervous system and cardiovascular compromise

Clinical Significance

Upper extremity nerve blocks can complement general anesthesia and are effective as surgical and postoperative analgesia. Using nerve blocks to target the brachial plexus reduces intraoperative and postoperative opioid requirements and decreases opioid-related adverse effects like respiratory depression, oversedation, and nausea and vomiting. Ultrasound guidance has become the standard of care when performing the interscalene, supraclavicular, infraclavicular, and axillary blocks. This multimodal pain management has also been shown to increase both patient and surgeon satisfaction.[7]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Ultrasonography is the preferred method for direct visualization and localization of the targeted nerve. Recent research shows that using ultrasound as a standard of care has had beneficial and positive effects on patient satisfaction, surgeon satisfaction, duration and intensity of analgesia, overall procedure time, block time to onset, and reduced overall adverse outcomes. Direct visualization of the needle under ultrasound guidance can help experienced providers avoid intraneural injection and injury, intravascular anesthetic injection, and possibly local anesthetic toxicity. Studies thus far are on a smaller scale and encompass expert opinions; future studies should be done on a larger scale to confirm these opinions and reaffirm the findings from smaller studies.[8][9] [Level III]

In a team setting, closed-loop communication must exist. All consents should be signed after specific risks, benefits, and expectations have been explained in detail to the patient. All patients should have a proper procedural timeout performed. The patient's name, date of birth, pertinent allergies, and procedure should be confirmed by all providers and the patient. Site verification and laterality must be confirmed. Implementing guidelines and checklists has proven to reduce the occurrence of adverse outcomes such as surgeon-anesthesiologist miscommunications and wrong-site or wrong-side regional anesthesia procedures.[10][11] [Level I]

All team members must communicate their concerns, responsibilities, and activities with all other team members contemporaneously and as indicated throughout the perioperative period, based on their professional discretion. All team members should respect the free flow of information and concerns among team members without allowing or producing an environment of hostility. All interprofessional team members should consider it their duty to neither disrupt the work performed by other team members nor to, through their actions or inaction, create additional issues or increase the workload for other team members. [Level V]

Media

References

Prabhakar A, Lambert T, Kaye RJ, Gaignard SM, Ragusa J, Wheat S, Moll V, Cornett EM, Urman RD, Kaye AD. Adjuvants in clinical regional anesthesia practice: A comprehensive review. Best practice & research. Clinical anaesthesiology. 2019 Dec:33(4):415-423. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2019.06.001. Epub 2019 Jul 2 [PubMed PMID: 31791560]

Forro SD, Munjal A, Lowe JB. Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Arm Structure and Function. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29939618]

Zhang Y, Cui B, Gong C, Tang Y, Zhou J, He Y, Liu J, Yang J. A rat model of nerve stimulator-guided brachial plexus blockade. Laboratory animals. 2019 Apr:53(2):160-168. doi: 10.1177/0023677218779608. Epub 2018 Jul 26 [PubMed PMID: 30049253]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVaid VN, Shukla A. Inter Scalene Block: Revisiting old technique. Anesthesia, essays and researches. 2018 Apr-Jun:12(2):344-348. doi: 10.4103/aer.AER_231_17. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29962595]

Stasiowski M, Zuber M, Marciniak R, Kolny M, Chabierska E, Jałowiecki P, Pluta A, Missir A. Risk factors for the development of Horner's syndrome following interscalene brachial plexus block using ropivacaine for shoulder arthroscopy: a randomised trial. Anaesthesiology intensive therapy. 2018:50(3):215-220. doi: 10.5603/AIT.a2018.0013. Epub 2018 Jun 22 [PubMed PMID: 29931665]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDhir S, Brown B, Mack P, Bureau Y, Yu J, Ross D. Infraclavicular and supraclavicular approaches to brachial plexus for ambulatory elbow surgery: A randomized controlled observer-blinded trial. Journal of clinical anesthesia. 2018 Aug:48():67-72. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2018.05.005. Epub 2018 May 26 [PubMed PMID: 29778971]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBerninger MT, Friederichs J, Leidinger W, Augat P, Bühren V, Fulghum C, Reng W. Effect of local infiltration analgesia, peripheral nerve blocks, general and spinal anesthesia on early functional recovery and pain control in total knee arthroplasty. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2018 Jul 18:19(1):232. doi: 10.1186/s12891-018-2154-z. Epub 2018 Jul 18 [PubMed PMID: 30021587]

Magazzeni P, Jochum D, Iohom G, Mekler G, Albuisson E, Bouaziz H. Ultrasound-Guided Selective Versus Conventional Block of the Medial Brachial Cutaneous and the Intercostobrachial Nerves: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Regional anesthesia and pain medicine. 2018 Nov:43(8):832-837. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000823. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29905631]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBarrington MJ, Uda Y. Did ultrasound fulfill the promise of safety in regional anesthesia? Current opinion in anaesthesiology. 2018 Oct:31(5):649-655. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0000000000000638. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30004951]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHopping M, Merry AF, Pandit JJ. Exploring performance of, and attitudes to, Stop- and Mock-Before-You-Block in preventing wrong-side blocks. Anaesthesia. 2018 Apr:73(4):421-427. doi: 10.1111/anae.14167. Epub 2017 Dec 27 [PubMed PMID: 29280131]

Slocombe P, Pattullo S. A site check prior to regional anaesthesia to prevent wrong-sided blocks. Anaesthesia and intensive care. 2016 Jul:44(4):513-6 [PubMed PMID: 27456184]