Introduction

Urinary incontinence is the involuntary leakage of urine.[1] This medical condition is common in the elderly, especially in nursing homes, but it can affect younger adult males and females as well. Urinary incontinence can impact both patient health and quality of life. The prevalence may be underestimated as some patients do not inform health care providers of having issues with urinary incontinence for various reasons.[2]

Several different types of urinary incontinence exist, including stress urinary incontinence, urge urinary incontinence, functional incontinence, mixed incontinence, and overflow incontinence. In most cases, urologic or gynecologic assessment is not necessary during the initial evaluation, but reversible causes should be ruled out. The management of urinary incontinence depends upon which type of incontinence is present and the severity of the symptoms.[3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The 5 types of urinary incontinence and their causes are listed below:[1][3]

- Stress urinary incontinence is the involuntary leakage of urine that occurs with increases in intraabdominal pressure (e.g., with exertion, effort, sneezing, or coughing) due to urethral sphincter and/or pelvic floor weakness. Young women active in sports may experience this type of incontinence.[4] In addition, pregnant women and women who have experienced childbirth may be prone to stress urinary incontinence.

- Urge urinary incontinence is the involuntary leakage of urine that may be preceded or accompanied by a sense of urinary urgency (but can be asymptomatic as well) due to detrusor overactivity. The contractions may be caused by bladder irritation or loss of neurologic control.

- Mixed urinary incontinence is the involuntary leakage of urine caused by a combination of stress and urge urinary incontinence as described above.

- Overflow urinary incontinence is the involuntary leakage of urine from an overdistended bladder due to impaired detrusor contractility and/or bladder outlet obstruction. Neurologic diseases such as spinal cord injuries, multiple sclerosis, and diabetes can impair detrusor function. Bladder outlet obstruction can be caused by external compression by abdominal or pelvic masses and pelvic organ prolapse, among other causes. A common cause in men is benign prostatic hyperplasia.

- Functional urinary incontinence is the involuntary leakage of urine due to environmental or physical barriers to toileting. This type of incontinence is sometimes referred to as toileting difficulty.

Epidemiology

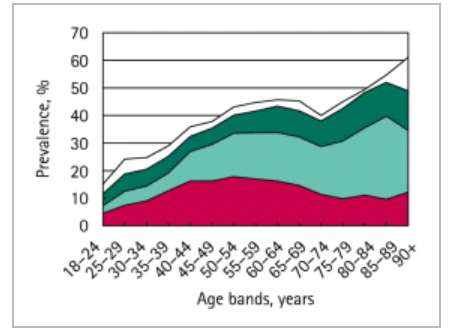

Accurate prevalence data is difficult to obtain due to issues such as underreporting, use of differing definitions for urinary incontinence, and varying study designs.[5][6]

It is estimated that around 423 million people (20 years and older) worldwide experience some form of urinary incontinence.[7]

Approximately 13 million Americans experience urinary incontinence. The prevalence is 50% or greater among residents of nursing facilities. Caregivers report that 53% of the homebound elderly are incontinent. A random sampling of hospitalized elderly patients reports that 11% of patients have persistent urinary incontinence at admission, and 23% at discharge.[6]

24% to 45% of women report some degree of urinary incontinence. 7% to 37% of women ages 20 to 39 report some degree of urinary incontinence. Daily urinary incontinence is reported by 9% to 39% of women over age 60. Increased risk of urinary incontinence was associated with pregnancy, childbirth, diabetes, and increased body mass index. 11% to 34% of older men report urinary incontinence, with 2 to 11% reporting daily occurrences. Increased risk is associated with prostate surgery.[5] In general, the prevalence of men is about half that of women.[6]

The estimated prevalence for the types of urinary incontinence are as follows:[3]

- Stress urinary incontinence – 24% to 45% in women over 30 years

- Urge urinary incontinence – 9% in women 40 to 44 years; 31% in women over 75 years; 42% in men over 75 years

- Mixed urinary incontinence – 20% to 30% of those with chronic incontinence

- Overflow urinary incontinence – 5% of those with chronic incontinence

- Functional urinary incontinence – Uncertain

History and Physical

History

The history should be used to determine the type, severity, burden, and duration of urinary incontinence. Voiding diaries may help provide details about episodes of incontinence. Signs and symptoms pertaining to emergent conditions (such as cauda equina syndrome) and reversible causes should be queried.

The type of urinary incontinence can often be determined by the history:

- Stress urinary incontinence – Patients can predict the inciting activity.

- Urge urinary incontinence – Frequency, urgency, and nocturia may be present. There is variable volume loss, ranging from none to flooding.

- Mixed urinary incontinence – There are characteristics of both stress and urge incontinence. Determine which component is most predominant and bothersome.

- Overflow urinary incontinence – This condition is associated with poor bladder emptying. The patient may endorse straining.

- Functional urinary incontinence – The history may suggest physical or cognitive impairment.

The 3 incontinence questions (3IQ) is a brief questionnaire that may be useful to distinguish among stress, urge, mixed urinary incontinence, and other causes. The 3IQ predicts stress urinary incontinence with a specificity of up to 92%, but its utility may depend on the population studied.[8][9]

Patients should be asked about medical conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma (which can cause cough), heart failure (with related fluid overload and diuresis), neurologic conditions (which may suggest dysregulated bladder innervation), musculoskeletal conditions (which may contribute to toileting barriers), etc.

The surgical history should also be assessed as the involved anatomy and innervation may have been affected.

For females, a gynecologic history should be obtained to assess for the number of births, whether births were vaginal or by c-section, and whether or not they are currently pregnant. In addition, estrogen status should be determined as atrophic vaginitis and urethritis may contribute to reversible urinary incontinence during perimenopause.

Patients should be asked about medication and substance use (e.g., diuretics, alcohol, caffeine), as they can either directly or indirectly contribute to incontinence. Potential adverse effects include impairment of cognition, alteration of bladder tone or sphincter function, inducement of cough, promotion of diuresis, etc.

Symptom severity is asked about to determine the aggressiveness of treatment.[3][10]

Physical

The history should guide the practitioner toward an appropriate physical exam. Again, emergent conditions and reversible causes should be explored.

The following physical exam components and findings should be assessed if appropriate:[3][10]

- Cardiovascular - pedal edema, jugular venous distension

- Pulmonary - pulmonary crackles, cough

- Abdominal - masses, surgical scars

- Musculoskeletal - extremity strength, range of motion, and overall function

- Genitourinary/rectal - bladder distension, vaginal atrophy, pelvic organ prolapse, prostatic hypertrophy, fecal impaction, rectal tone

- Neurologic - cognitive function, sensory, reflexes

Tests and maneuvers to consider, but are not necessary, are:

- Cough stress test - The patient is asked to cough to demonstrate involuntary leakage of urine. The test is more sensitive when done in a standing position.[10]

- Cotton swab test - The patient is asked to Valsalva after insertion of a swab placed into the bladder through the urethra to demonstrate urethral hypermobility (associated with stress urinary incontinence), with an angle change of greater than 30 degrees being a positive result. There may be poor agreement of the test result when the angle is from 21 to 49 degrees.[11]

Evaluation

The evaluation should include:[3][10][12]

- A focused, but thorough history and physical

- A search for reversible causes

- Medication reconciliation

Very little laboratory testing or imaging is required for evaluation. Most laboratory and diagnostic tests are for ruling out harmful conditions and sequelae.[3][10][12]

- Urinalysis should be performed on all patients to assess for urinary tract infection, glycosuria, proteinuria, hematuria.

- Blood urea nitrogen and creatinine can be performed if an obstruction is suspected, so that renal function can be assessed.

- Post-void residual volume can be done if overflow urinary incontinence is suspected. Bladder ultrasound is performed after a patient voids. Detection of greater than 200 mL of urine remaining in the bladder after voiding is suggestive for overflow urinary incontinence.

- Renal ultrasound can be considered to assess for hydronephrosis in cases suspicious for obstruction.

- Urodynamic testing is not necessary except for complicated cases or if surgery may be considered.

Treatment / Management

Treatment and management are dependent on the type of urinary incontinence. Conservative, pharmacologic, and surgical modalities exist. Treatment and management should begin with the least invasive methods and then escalate as appropriate:[3][10][13](A1)

- Stress urinary incontinence

- Conservative management - behavioral therapy (controlling fluid intake, prompted voiding, constipation management, etc.), electrical stimulation, mechanical devices (cones, pessaries, urethral plugs), pelvic floor muscle strengthening (Kegel and floor muscle exercises), weight loss

- Pharmacologic management - alpha-adrenergic agonists (e.g., phenylpropolamine),[14] duloxetine (not FDA approved)

- Surgical management - intravesical balloons, trans- or periurethral injections of bulking agents, sling procedures, urethropexy

- Urge urinary incontinence

- Conservative management - similar to the treatment for stress urinary incontinence with the exception of mechanical devices

- Pharmacologic management - antimuscarinics (e.g., darifenacin, solifenacin, oxybutynin, tolterodine, fesoterodine, trospium),[15] topical vaginal estrogen (not FDA approved), mirabegron

- Surgical management - neuromodulation, onabotulinumtoxinA injection

- Mixed urinary incontinence

- Treatment and management as above, focusing on dominant symptoms

- Overflow urinary incontinence

- Conservative management - clean intermittent catheterization, indwelling urethral catheter, relief of obstruction

- Pharmacologic management - alpha-adrenergic antagonists (e.g. terazosin, tamsulosin)[14]

- Surgical management - suprapubic catheter

- Functional urinary incontinence

- Underlying causes should be addressed or alleviated if possible

Medications should be reconciled, and substances such as caffeine and alcohol should be avoided if they are contributing to incontinence.

Urinary incontinence in end of life care can be difficult to manage and should be handled on a case by case basis. In some instances, an indwelling catheter or condom catheter may need to be used to maximize comfort for the patient in the last stages of their life.

Differential Diagnosis

The mnemonic DIAPPERS can be used as an aid to develop a differential diagnosis for reversible causes of urinary incontinence:[3]

- Delirium, dementia, or other cognitive impairments

- Infection (urinary tract infection)

- Atrophic vaginitis or urethritis

- Pharmaceuticals or substances (e.g., diuretics, caffeine, alcohol)

- Psychological disorder

- Excessive urine output (e.g., diabetes, diabetes insipidus)

- Reduced mobility or reversible urinary retention

- Stool impaction

Other conditions to consider include:

- Neurologic conditions such as spinal cord injuries, cauda equina syndrome, multiple sclerosis, cerebral vascular accidents, normal pressure hydrocephalus, spinal stenosis

- Renal or ureteral calculi

- Intraabdominal or pelvic mass

- Anatomic abnormalities such as urogenital fistulas, diverticula, and ectopic ureters (though these are less common)[16]

Prognosis

Response to treatment and management is variable among patients. In those whose symptoms cannot be completely eliminated, optimal symptom control should be sought by multiple treatment modalities. Median cure rates for stress, urge, and mixed urinary incontinence by select modalities can be seen below:[17]

- Stress urinary incontinence

- 84.4% at 12 months for women that received surgical interventions

- 53% after 3 years for males that received slings

- 58.8% at 12 months for women that used supervised pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT)

- 78% at 6 months for men that used PFMT

- Urge urinary incontinence

- 49% at 12 months for women that used antimuscarinics

- 17% at 10 years for women that used sacral neuromodulation

- 15.9% to 50.9% at 3 months in women that used onabotulinumtoxinA

- 24% to 35% at 12 months for men that used supervised PFMT

- Mixed urinary incontinence

- 82.3% for women that received surgical interventions

- 47% for men that used supervised PFMT

- 28% at 6 months for women with supervised PFMT

Several inventories and tools exist that may be used to monitor symptoms and treatment effectiveness:

- Michigan incontinence symptom index (M-ISI) - This questionnaire assesses the frequency of urinary incontinence, the amount of protection used, and the impact of urinary incontinence on daily activities.[18]

- International consultation on incontinence questionnaire-short form (ICIQ-UI short form) - The questionnaire has high intra and interobserver reliability.[19]

- Sandvik questionnaire (incontinence severity index) - This questionnaire assesses frequency and amount of leakage, and has a high correlation with the ICIQ-UI short form.[20]

Complications

Complications related to urinary incontinence include:[10][14][21]

- Urinary tract infections

- Renal dysfunction secondary to obstructive uropathy

- Cellulitis

- Pressure ulcers

- Medication side effects

- Alpha-adrenergic agonists side effects:[14] dry mouth, restlessness, hypertension, insomnia

- Duloxetine:[22] dry mouth, nausea, fatigue, constipation, hyperhidrosis

- Antimuscarinic side effects:[17] dry mouth, constipation, blurred vision, dry eyes, fatigue, difficulty in micturition, palpitations

- Mirabegron:[23] urinary tract infections, hypertension, dry mouth

- OnabotulinumtoxinA injection:[22] urinary tract infections, urinary retention

- Alpha-adrenergic antagonists:[22] hypotension, dizziness, fatigue, sedation

- Trauma and infection due to catheterization

- Worsening of urinary incontinence after surgical intervention

- Increased risk of falls and subsequent fractures

- Decreased physical activity

- Sexual dysfunction

- Depression

- Social isolation

- Increased caregiver burden

Consultations

A urologic referral is recommended in the following situations:[3]

- Incontinence associated with relapse

- Incontinence associated with recurrent symptomatic urinary tract infections

- Incontinence with new-onset neurologic symptoms

- Marked prostate enlargement

- Pelvic organ prolapsed past the introitus

- Pelvic pain associated with incontinence

- Persistent hematuria

- Persistent proteinuria

- Postvoid residual volume greater than 200 mL

- Previous pelvic surgery or radiation

- Uncertain diagnosis

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should be informed that although urinary incontinence is highly prevalent in older adults, it is not a normal part of aging. They should be aware that some causes of urinary incontinence are reversible. Information should be available to patients regarding the various treatment and management options that are available, which include conservative, pharmacologic, and surgical modalities.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Despite being a highly prevalent condition, urinary incontinence is inadequately screened for by health care providers. As a result, a large number of patients with urinary incontinence are without treatment, having to tolerate suboptimal health and quality of life. Health care providers in various settings such as hospitals, clinics, and nursing homes can better screen for and communicate findings of patient urinary incontinence with one another to better facilitate patient care. In a collaborative approach, nurses and medical assistants can help screen patients for urinary incontinence. Pharmacists can provide assistance with medication reconciliation in relevant cases. In more complicated cases of urinary incontinence, collaboration among primary care clinicians and specialists is needed to deliver the seamless, quality care to patients. A study intended to increase screening and management of urinary incontinence by primary care clinicians was unsuccessful despite additional training and support offered to them. The study focused primarily on clinicians and not other health care providers.[24] [Level 3]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, Griffiths D, Rosier P, Ulmsten U, Van Kerrebroeck P, Victor A, Wein A, Standardisation Sub-Committee of the International Continence Society. The standardisation of terminology in lower urinary tract function: report from the standardisation sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Urology. 2003 Jan:61(1):37-49 [PubMed PMID: 12559262]

Lukacz ES, Santiago-Lastra Y, Albo ME, Brubaker L. Urinary Incontinence in Women: A Review. JAMA. 2017 Oct 24:318(16):1592-1604. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.12137. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29067433]

Khandelwal C, Kistler C. Diagnosis of urinary incontinence. American family physician. 2013 Apr 15:87(8):543-50 [PubMed PMID: 23668444]

Alves JO, Luz STD, Brandão S, Da Luz CM, Jorge RN, Da Roza T. Urinary Incontinence in Physically Active Young Women: Prevalence and Related Factors. International journal of sports medicine. 2017 Nov:38(12):937-941. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-115736. Epub 2017 Sep 26 [PubMed PMID: 28950397]

Buckley BS, Lapitan MC, Epidemiology Committee of the Fourth International Consultation on Incontinence, Paris, 2008. Prevalence of urinary incontinence in men, women, and children--current evidence: findings of the Fourth International Consultation on Incontinence. Urology. 2010 Aug:76(2):265-70. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.11.078. Epub 2010 Jun 11 [PubMed PMID: 20541241]

. Managing acute and chronic urinary incontinence. AHCPR Urinary Incontinence in Adults Guideline Update Panel. American family physician. 1996 Oct:54(5):1661-72 [PubMed PMID: 8857788]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceIrwin DE, Kopp ZS, Agatep B, Milsom I, Abrams P. Worldwide prevalence estimates of lower urinary tract symptoms, overactive bladder, urinary incontinence and bladder outlet obstruction. BJU international. 2011 Oct:108(7):1132-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09993.x. Epub 2011 Jan 13 [PubMed PMID: 21231991]

Brown JS, Bradley CS, Subak LL, Richter HE, Kraus SR, Brubaker L, Lin F, Vittinghoff E, Grady D, Diagnostic Aspects of Incontinence Study (DAISy) Research Group. The sensitivity and specificity of a simple test to distinguish between urge and stress urinary incontinence. Annals of internal medicine. 2006 May 16:144(10):715-23 [PubMed PMID: 16702587]

Khan MJ, Omar MA, Laniado M. Diagnostic agreement of the 3 Incontinence Questionnaire to video-urodynamics findings in women with urinary incontinence: Department of Urology, Frimley Health NHS Foundation Trust Wexham Park Hospital Slough, Berkshire, United Kingdom. Central European journal of urology. 2018:71(1):84-91. doi: 10.5173/ceju.2018.1622. Epub 2017 Feb 21 [PubMed PMID: 29732212]

Hu JS, Pierre EF. Urinary Incontinence in Women: Evaluation and Management. American family physician. 2019 Sep 15:100(6):339-348 [PubMed PMID: 31524367]

Swift S, Barnes D, Herron A, Goodnight W. Test-retest reliability of the cotton swab (Q-tip) test in the evaluation of the incontinent female. International urogynecology journal. 2010 Aug:21(8):963-7. doi: 10.1007/s00192-010-1135-z. Epub 2010 Apr 9 [PubMed PMID: 20379698]

. Committee Opinion No. 603: Evaluation of uncomplicated stress urinary incontinence in women before surgical treatment. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2014 Jun:123(6):1403-1407. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000450759.34453.31. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24848922]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSubak LL, Quesenberry CP, Posner SF, Cattolica E, Soghikian K. The effect of behavioral therapy on urinary incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2002 Jul:100(1):72-8 [PubMed PMID: 12100806]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceImam KA. The role of the primary care physician in the management of bladder dysfunction. Reviews in urology. 2004:6 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S38-44 [PubMed PMID: 16985854]

Gormley EA, Lightner DJ, Burgio KL, Chai TC, Clemens JQ, Culkin DJ, Das AK, Foster HE Jr, Scarpero HM, Tessier CD, Vasavada SP, American Urological Association, Society of Urodynamics, Female Pelvic Medicine & Urogenital Reconstruction. Diagnosis and treatment of overactive bladder (non-neurogenic) in adults: AUA/SUFU guideline. The Journal of urology. 2012 Dec:188(6 Suppl):2455-63. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.09.079. Epub 2012 Oct 24 [PubMed PMID: 23098785]

Morhason-Bello IO, Adebayo SA, Abdusalam RA, Bello OO, Odubamowo KH, Lawal OO, Olapade-Olaopa EO, Ojengbede OA. Bilateral double ureters with bladder neck diverticulum in a nigerian woman masquerading as an obstetric fistula. Case reports in urology. 2014:2014():801063. doi: 10.1155/2014/801063. Epub 2014 Dec 23 [PubMed PMID: 25587483]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRiemsma R, Hagen S, Kirschner-Hermanns R, Norton C, Wijk H, Andersson KE, Chapple C, Spinks J, Wagg A, Hutt E, Misso K, Deshpande S, Kleijnen J, Milsom I. Can incontinence be cured? A systematic review of cure rates. BMC medicine. 2017 Mar 24:15(1):63. doi: 10.1186/s12916-017-0828-2. Epub 2017 Mar 24 [PubMed PMID: 28335792]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSuskind AM, Dunn RL, Morgan DM, DeLancey JO, McGuire EJ, Wei JT. The Michigan Incontinence Symptom Index (M-ISI): a clinical measure for type, severity, and bother related to urinary incontinence. Neurourology and urodynamics. 2014 Sep:33(7):1128-34. doi: 10.1002/nau.22468. Epub 2013 Aug 14 [PubMed PMID: 23945994]

Hajebrahimi S, Corcos J, Lemieux MC. International consultation on incontinence questionnaire short form: comparison of physician versus patient completion and immediate and delayed self-administration. Urology. 2004 Jun:63(6):1076-8 [PubMed PMID: 15183953]

Klovning A, Avery K, Sandvik H, Hunskaar S. Comparison of two questionnaires for assessing the severity of urinary incontinence: The ICIQ-UI SF versus the incontinence severity index. Neurourology and urodynamics. 2009:28(5):411-5. doi: 10.1002/nau.20674. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19214996]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceStickley A, Santini ZI, Koyanagi A. Urinary incontinence, mental health and loneliness among community-dwelling older adults in Ireland. BMC urology. 2017 Apr 8:17(1):29. doi: 10.1186/s12894-017-0214-6. Epub 2017 Apr 8 [PubMed PMID: 28388898]

Demaagd GA, Davenport TC. Management of urinary incontinence. P & T : a peer-reviewed journal for formulary management. 2012 Jun:37(6):345-361H [PubMed PMID: 22876096]

Chapple CR, Cardozo L, Nitti VW, Siddiqui E, Michel MC. Mirabegron in overactive bladder: a review of efficacy, safety, and tolerability. Neurourology and urodynamics. 2014 Jan:33(1):17-30. doi: 10.1002/nau.22505. Epub 2013 Oct 11 [PubMed PMID: 24127366]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBland DR, Dugan E, Cohen SJ, Preisser J, Davis CC, McGann PE, Suggs PK, Pearce KF. The effects of implementation of the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research urinary incontinence guidelines in primary care practices. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2003 Jul:51(7):979-84 [PubMed PMID: 12834518]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceYao M, Simoes A. Urodynamic Testing and Interpretation. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32965981]