Introduction

Pulmonary embolism (PE) secondary to venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a major preventable cause of mortality in hospitalized patients. Prophylactic anticoagulation with mechanical and pharmacological therapies is indicated for high-risk patients. Pharmacological anticoagulation is the first-line treatment for newly diagnosed VTE and pulmonary embolism. Inferior vena cava (IVC) filter is a treatment option to prevent pulmonary embolism in a select group of patients that have venous thromboembolism (VTE) and absolute contraindication to anticoagulation, failure of anticoagulation, complications resulting from anticoagulation or progression of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) despite adequate anticoagulation.[1][2]

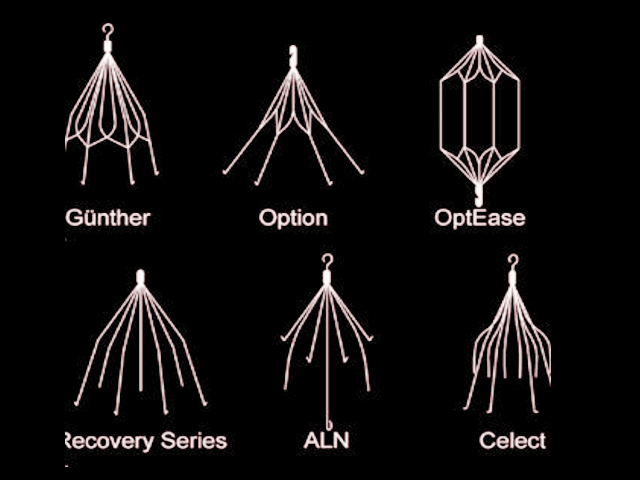

The Greenfield inferior vena cava filter came on the market in 1973. Currently, there are two categories of IVC filters in use: permanent and retrievable. The use of IVC filters has increased since the advent of retrievable IVC filters that were approved by the FDA in 2003 and 2004.[3]

Most studies have not shown any difference in the all-cause mortality in deep venous thrombosis (DVT) patients treated with IVC filters compared to the ones treated with anticoagulation therapy alone. Prophylactic IVC filters are sometimes inserted in patients at high risk of developing venous thromboembolism (VTE), especially if there is a contraindication to anticoagulation. These studies have not shown any mortality benefit. In fact, IVC filters correlate with an increased risk of recurrent deep vein thrombosis and other complications.[4]

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

To accurately place the filter and avoid complications, it is essential to be well-versed with the normal as well as variant anatomy of the inferior vena cava. As the common femoral vein passes below the inguinal ligament, it continues as the external iliac vein. When joined by the internal iliac vein, it forms the common iliac vein. The right and left common iliac veins coalesce to form the inferior vena cava at the L5 vertebral level. The inferior vena cava is divided into suprarenal and infrarenal portions by the right and left renal veins that merge into the inferior vena cava at L1 to L2 level.

Duplicate inferior vena cava (IVC) is a congenital anomaly present in about 2% of the population. This condition should be a consideration in cases where there is a recurrence of pulmonary embolism even after the placement of an IVC filter. This anomaly mostly occurs due to the failure of the regression of the left supra cardinal vein. Another common anomaly of the inferior vena cava is the circumaortic left renal vein. In these patients placing the IVC filter below the entry of the renal vein can be challenging due to the short distance between the renal vein and the iliac vein. In these cases, either a suprarenal IVC filter or two filters in both common iliac veins merits consideration. On imaging, clinicians can mistake these anomalies as retroperitoneal adenopathy.[5][2]

An inferior vena cava measuring greater than 28 mm is known as mega vena cava. The typical commercially available IVC filter covers a vena cava of up to 28 mm in diameter, but the bird’s nest filter is an option in an IVC of up to 40 mm in diameter.[6]

Indications

Guidelines like the American Heart Association (AHA), American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) and American College of Radiology (ACR)/Society of Interventional Radiology (SIR) recommend the use of inferior vena cava (IVC) filters in patients that have venous thromboembolic disease (VTE) and an absolute contraindication to anticoagulation, complications necessitating cessation of anticoagulation, or who have recurrent VTE despite adequate anticoagulation.[7]

With the advent of retrievable filters, IVC filter insertion has increased in patients other than those mentioned above, paving the way for expanded/relative indications for IVC filter insertion. These include patients with VTE and massive pulmonary embolism (PE) that are at high risk of recurrent embolism, poor compliance with anticoagulant use, limited cardiopulmonary reserve, large free-floating proximal deep vein thrombosis (DVT), patients at high risk of complications of anticoagulant use and cancer-associated VTE. Although the relative indications for IVC filters have expanded, many studies have shown that a large number of these filters are never retrieved. Guidelines for the use of IVC filters in such expanded/relative indications are sparse. Due to the lack of randomized controlled trials, the use of IVC filters in these cases depends mostly on the physician's judgment.[1][8]

In clinical practice, clinicians sometimes use IVC filters prophylactically in patients at high risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE). These include patients with long term immobilization (e.g., secondary to extensive trauma and surgical procedures) and certain medical conditions that induce a hypercoagulable state (e.g., cancer). A randomized controlled trial compared two groups of patients presumed to be at high risk for DVT; one group received a permanent IVC filter and the other low-molecular-weight heparin with adjusted dose IV heparin. The group that received a permanent IVC filter initially showed a reduced incidence of pulmonary embolism, but there were no immediate or long term differences in mortality. After a follow-up of two years, the incidence of recurrent DVT in the IVC filter group was significantly higher.[9][1]

Contraindications

Inferior vena cava filter insertion is generally considered safe. There are no known absolute contraindications to IVC filter placement; some relative contraindications to IVC filter use include severe uncorrectable coagulopathy and bacteremia.[2]

Equipment

- Inferior vena cava (IVC) filter

- Catheter

- X-ray machine

- Ultrasound machine

- Local anesthetic

- IV line

- Sedative

- Contrast dye

Personnel

- Interventional radiologist

- Nurse

- Technologist

Preparation

During the planning phase, laboratory tests like coagulation profile and renal function tests are important to assess the bleeding risk and make a decision regarding contrast use. The patient should be informed to stop all solid foods eight hours before the procedure and liquids two hours before the procedure. A review of the patient's medications and necessary adjustment is crucial, as well.

Cross-sectional imaging can be extremely useful in assessing the inferior vena cava (IVC) as well as the access site. In the absence of prior imaging, cavography should be performed to look for duplication or other anomalies of the IVC, the diameter of the vena cava, and the presence of clots.[6]

Technique or Treatment

Inferior Vena Cava (IVC) filters are mostly placed in the inpatient setting due to the need for active management of venous thromboembolism (VTE), though placement can also occur as an outpatient procedure. An internal jugular or femoral access is mostly used to place the IVC filter. Irrespective of the access vessel, a right-sided approach is preferred due to the direct path to the inferior vena cava and minimal tilt. Comfort, ease, and a comparatively straight course make the right internal jugular vein the more common choice; this approach also decreases the risk of interference with a thrombus, if present in the femoral or iliac vein. However, the femoral vein approach is preferable for patients with central venous catheters, intubated patients, or when using intravascular ultrasound.[2][6]

Different imaging modalities are available for guidance during the placement of an IVC filter. These include fluoroscopy, duplex ultrasound, and intravascular ultrasound (IVUS). Fluoroscopy done in an interventional suite is the most common imaging modality used. However, duplex ultrasound or IVUS is an approach in individual patients who cannot be transported to the interventional suite and require bedside insertion of the filter.[2][6]

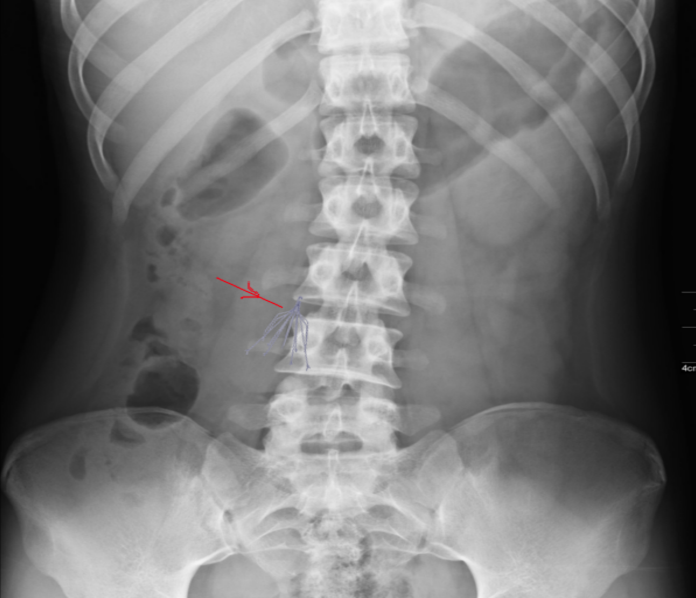

After sterile preparation of the access site, a small incision is made, and a catheter is inserted, ideally under fluoroscopic guidance. The filter is then pushed along the catheter and deployed. The most common location for IVC filter placement is just inferior to the inflow of the renal veins. This site is preferable due to the minimal risk of thrombus occluding the renal veins. The IVC filter can be placed in the suprarenal IVC in some instances like pregnancy, thrombus in the infrarenal location, and other conditions in which IVC filter placement in the infrarenal location is not feasible.[2][6]

Complications

Complications related to using inferior vena cava filters fall into the following categories; those occurring during the procedure, following the procedure, and during retrieval.

- Procedure: During the vascular access for IVC filter insertion, bleeding and thrombosis are the most common complications. Other complications that can occur during this time include filter tilt (angulation of more than 15 degrees along the longitudinal axis of IVC), filter migration (change in position of the filter by more than 2 cm) or operator error (filter placement in the inaccurate location or incorrect orientation); these can result in a difficult to retrieve as well as an ineffective IVC filter.

- Post-procedure: 1) IVC thrombosis can occur, resulting in pain and edema of bilateral lower extremities; this can also result in an increased risk of a pulmonary embolism due to the thrombus extending above the filter and embolizing to the lungs. 2) Renal failure is another dreaded complication that can occur in case the thrombus extends to the suprarenal IVC. 3) There is a possibility of inferior vena cava penetration by the IVC filter. Hooks were added to the filters to decrease the incidence of filter migration, but this has shown to increase inferior vena cava perforation rates significantly. 4) Filter fracture can occur, resulting in fragmentation of the filter. These fragments can embolize to the heart and lungs.

- Retrieval: The longer the time that the filter remains in place, the greater the rate of complications during retrieval. Some of the most commonly noted complications during filter retrieval include fracture and IVC injury (e.g., dissection). Thus removal of IVC filter as soon as it is no longer needed is highly recommended.[10]

As compared to permanent IVC filters, complications occur much more frequently with the use of retrievable IVC filters.[11] Fracture is the most common complication of retrievable IVC filters, and placement malfunction occurs more commonly with permanent IVC filters.[12]

Clinical Significance

Due to the lack of prospective studies, the use of inferior vena cava (IVC) filters has remained controversial, with physicians mostly relying on their clinical judgment and experience. In terms of a mortality benefit, the PREPIC trial, the only randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effectiveness of IVC filters, failed to establish any significant survival benefit of using IVC filters over anticoagulant use alone. Although the PREPIC trial showed short term and long term advantage in preventing pulmonary embolism recurrence in patients receiving IVC filters, it also showed a significant increase in DVT recurrence in this group.[7] There is a pressing need for further randomized controlled trials to make a decision regarding the benefit of IVC filters, reduce their unnecessary use, and to compare the rates of complications among different types of devices that are in use.[8]

VTE remains a leading cause of maternal mortality, with a six times greater risk of death as compared to the normal population. Warfarin, due to its teratogenicity, is not a recommendation in these patients; LMWH is the appropriate choice, but in patients at high risk of bleeding like those with placenta previa or recurrent VTE, retrievable IVC filter placement can be considered.[1][6] One should note that because of IVC dilation in pregnancy, the risk of filter migration increases.[8]

With the advent of retrievable IVC filters, the use of IVC filters has increased. But due to the physicians not complying with the guidelines, failure of retrieval has been a significant concern. Different factors have correlations with the low retrieval rates; these include geographical variations in the retrieval rates, retrieval rates being higher in academic institutions as compared to others, and fewer retrieval rates in therapeutic as compared to prophylactic cases.[3] The placement of retrievable IVC filters is most common in patients with contraindications to anticoagulant therapy. But it is important to note that in the majority of cases, these contraindications are temporary, so as soon as it is appropriate to start anticoagulation, IVC filters should be removed to decrease the risk of recurrent DVT and IVC thrombus formation.[13] Removal should ideally take place within 30 days of insertion.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Considering the low retrieval rates of inferior vena cava (IVC) filters, complications associated with their use and lack of randomized controlled trials to show their efficacy in different subsets of patients, it is important to involve an interprofessional team consisting of an interventional radiologist, vascular surgeon, hospitalists, primary care providers, interventional cardiologist, hematologists, nurse practitioners and nurses to develop protocols that can result in improved retrieval rates and better patient selection for IVC filter placement.[14][15]

Patient education by nurses and physicians before the procedure, implementation of protocols, and post-procedure follow-up with a hematologist have all shown to improve the retrieval rate for IVC filters significantly.[15] [Level IV] Nurses should also be alert and aware of potential signs of adverse events, so they can intervene and inform the surgeon, preventing negative outcomes. Pharmacists will weigh in on anti-coagulant therapy, making dose adjustments, and performing a medication reconciliation to ensure there are no issues that can affect the IVC filter therapy.

Effective communication between hospitalists, primary care providers, nurses, and interventional radiologists has the potential for decreasing unnecessary filter insertion and improving retrieval rates, especially in situations of prophylactic use. A thorough history by the hospitalists and primary care providers can help in making a better decision regarding IVC filter insertion. IVC filters have not shown any mortality benefit over anticoagulation alone. They have shown some advantage in preventing pulmonary embolism recurrence but at the expense of significantly increased risk of deep vein thrombosis recurrence.[7] [Level II]

All of the above highlights the need for interprofessional team coordination between all disciplines when considering IVC filters in the management of a patient; this will result in improved outcomes. [Level V]

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

During the pre-procedure time, patient education by the nurses has shown to improve follow-up and IVC filter retrieval rates. Nurses can play a vital part in the formation of a structured program for effective and timely removal of the inferior vena cava (IVC) filters. They can maintain a comprehensive chart and call patients for follow-up. [15]

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Monitoring

Nurses should have a strong fundamental knowledge of complications related to inferior vena cava (IVC) filter use. Close monitoring for the development of complications can decrease both morbidity and mortality in patients.

Media

References

DeYoung E, Minocha J. Inferior Vena Cava Filters: Guidelines, Best Practice, and Expanding Indications. Seminars in interventional radiology. 2016 Jun:33(2):65-70. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1581088. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27247472]

Molvar C. Inferior vena cava filtration in the management of venous thromboembolism: filtering the data. Seminars in interventional radiology. 2012 Sep:29(3):204-17. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1326931. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23997414]

Everhart D, Vaccaro J, Worley K, Rogstad TL, Seleznick M. Retrospective analysis of outcomes following inferior vena cava (IVC) filter placement in a managed care population. Journal of thrombosis and thrombolysis. 2017 Aug:44(2):179-189. doi: 10.1007/s11239-017-1507-z. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28550629]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBikdeli B, Chatterjee S, Desai NR, Kirtane AJ, Desai MM, Bracken MB, Spencer FA, Monreal M, Goldhaber SZ, Krumholz HM. Inferior Vena Cava Filters to Prevent Pulmonary Embolism: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2017 Sep 26:70(13):1587-1597. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.07.775. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28935036]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGhandour A, Partovi S, Karuppasamy K, Rajiah P. Congenital anomalies of the IVC-embryological perspective and clinical relevance. Cardiovascular diagnosis and therapy. 2016 Dec:6(6):482-492. doi: 10.21037/cdt.2016.11.18. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28123970]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDoe C, Ryu RK. Anatomic and Technical Considerations: Inferior Vena Cava Filter Placement. Seminars in interventional radiology. 2016 Jun:33(2):88-92. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1581089. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27247476]

Malhotra A, Kishore S, Trost D, Madoff DC, Winokur RS. Inferior Vena Cava Filters and Prevention of Recurrent Pulmonary Embolism. Seminars in interventional radiology. 2018 Jun:35(2):105-107. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1642038. Epub 2018 Jun 4 [PubMed PMID: 29872245]

Duffett L, Carrier M. Inferior vena cava filters. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis : JTH. 2017 Jan:15(1):3-12. doi: 10.1111/jth.13564. Epub 2016 Dec 26 [PubMed PMID: 28019712]

Decousus H, Leizorovicz A, Parent F, Page Y, Tardy B, Girard P, Laporte S, Faivre R, Charbonnier B, Barral FG, Huet Y, Simonneau G. A clinical trial of vena caval filters in the prevention of pulmonary embolism in patients with proximal deep-vein thrombosis. Prévention du Risque d'Embolie Pulmonaire par Interruption Cave Study Group. The New England journal of medicine. 1998 Feb 12:338(7):409-15 [PubMed PMID: 9459643]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGrewal S, Chamarthy MR, Kalva SP. Complications of inferior vena cava filters. Cardiovascular diagnosis and therapy. 2016 Dec:6(6):632-641. doi: 10.21037/cdt.2016.09.08. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28123983]

Desai TR, Morcos OC, Lind BB, Schindler N, Caprini JA, Hahn D, Warner D, Gupta N. Complications of indwelling retrievable versus permanent inferior vena cava filters. Journal of vascular surgery. Venous and lymphatic disorders. 2014 Apr:2(2):166-73. doi: 10.1016/j.jvsv.2013.10.050. Epub 2014 Jan 16 [PubMed PMID: 26993182]

Andreoli JM, Lewandowski RJ, Vogelzang RL, Ryu RK. Comparison of complication rates associated with permanent and retrievable inferior vena cava filters: a review of the MAUDE database. Journal of vascular and interventional radiology : JVIR. 2014 Aug:25(8):1181-5. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2014.04.016. Epub 2014 Jun 11 [PubMed PMID: 24928649]

Streiff MB, Agnelli G, Connors JM, Crowther M, Eichinger S, Lopes R, McBane RD, Moll S, Ansell J. Guidance for the treatment of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Journal of thrombosis and thrombolysis. 2016 Jan:41(1):32-67. doi: 10.1007/s11239-015-1317-0. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26780738]

Lim MY, Yamada R, Guimaraes M, Greenberg CS. Practice Patterns of Inferior Vena Cava Filter Placement and Factors That Predict Retrieval Rates: A Single-Center Institution and Review of the Literature. Journal of clinical medicine research. 2018 Oct:10(10):758-764. doi: 10.14740/jocmr3544w. Epub 2018 Sep 10 [PubMed PMID: 30214647]

Winters JP, Morris CS, Holmes CE, Lewis P, Bhave AD, Najarian KE, Shields JT, Charash W, Cushman M. A multidisciplinary quality improvement program increases the inferior vena cava filter retrieval rate. Vascular medicine (London, England). 2017 Feb:22(1):51-56. doi: 10.1177/1358863X16676658. Epub 2016 Nov 3 [PubMed PMID: 27811236]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence