Introduction

The term "vascular ring" (VR) refers to the structures that encircle and compress the esophagus and trachea, causing respiratory and gastrointestinal symptoms. VRs are divided into 2 broad categories: complete or incomplete (see Image. Vascular Ring).

Complete VRs encircle the trachea and esophagus entirely. These include a double aortic arch (DAA) and a right aortic arch (RAA) with an aberrant (retro-esophageal) left subclavian artery (see Image. Double Aortic Arch and Right Aortic Arch With Aberrant (Retroesophageal) Left Subclavian Artery). These are the most common types of vascular rings.[1][2] Incomplete VRs do not completely encircle the trachea and esophagus, although some compress either the trachea or esophagus. It usually includes an aberrant innominate artery, an aberrant right subclavian artery, and a pulmonary artery sling.[2]

An arch-sidedness is defined by the position of the aortic arch in relation to the trachea and the bronchi. A left aortic arch would be towards the left of the trachea and run over the left bronchus, whereas an RAA would be towards the right of the trachea and run over the right bronchus. A DAA is when 2 transverse aortic arches run over the trachea and both bronchi. Normally, the arch-sidedness is towards the left, and no arterial duct is behind the trachea or esophagus. In cases of the vascular ring, there is a patent vessel, an atretic vessel, or its remnants circling the trachea or esophagus.

DAA can be further divided into 3 main types. The dominant RAA with a smaller LAA (80%) is the most common. The dominant LAA is found in 10% and equal aortic arches in the rest 10%.

Depending on the site of the regression of the fourth aortic arch, RAA can be divided into 2 parts.[3] If regression is proximal to the left subclavian artery, it is called RAA with an aberrant (retro esophageal) left subclavian artery.[3] If regression is distal, it is called RAA with mirror image branching.[3] Around 50% of cases of the right-sided aortic arch are associated with an aberrant (retro-esophageal) left subclavian artery.[4] This often has a Kommerell diverticulum named after the radiologist Dr. Burckhard F Komerell, who reported this finding in 1936.[5] Kommerell diverticulum is an outpouching of the distal aorta and usually originates from the left arch.[5]

Pulmonary artery sling occurs when the left pulmonary artery originates from the right pulmonary artery, which crosses between the trachea and esophagus before entering the left lung, thus compressing the trachea. It is the only VR type with an indentation in the anterior esophagus on barium swallow.

Anomalous innominate artery originates later from the transverse arch and then crosses the trachea, causing anterior tracheal compression.

According to the International Congenital Heart Surgery Nomenclature and Database Committee, the classification system for vascular rings is as follows:

A. Complete vascular rings

- Double aortic arch (DAA)

I. Dominant right arch

II. Dominant left arch

III. Equal arches/balanced arches

- Right aortic arch (RAA)

I. RAA+ aberrant left subclavian artery (ALSA)

II. RAA with mirror imaging

B. Incomplete aortic arch

- Innominate artery compression syndrome

- Pulmonary artery sling

- Aberrant right subclavian artery (ARSA) [1]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

DAA's exact cause is unknown nor for any other VR. There have been associations of RAA and DAA with 22q11 deletion in the literature.[6] There is some association of DAA with trisomy 21 and trisomy 18.[7] A left aortic arch with aberrant (retro-esophageal) right subclavian artery is not a ring but is highly associated with trisomy 21.

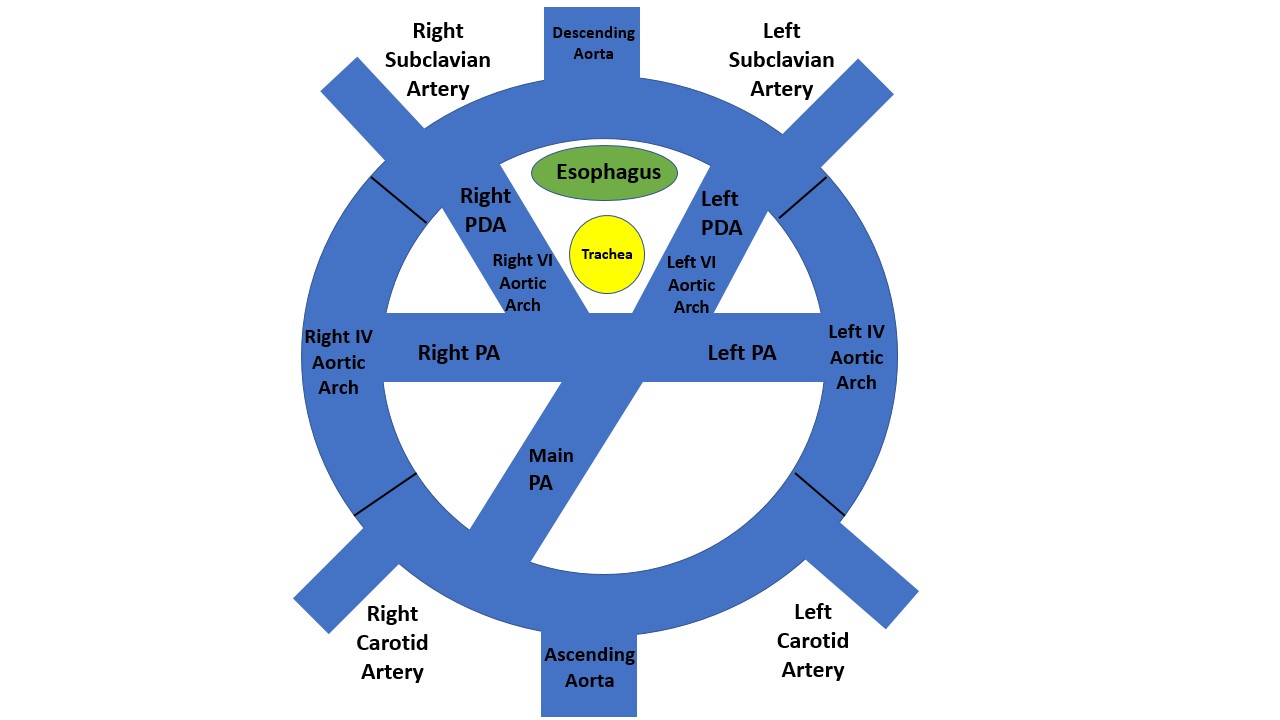

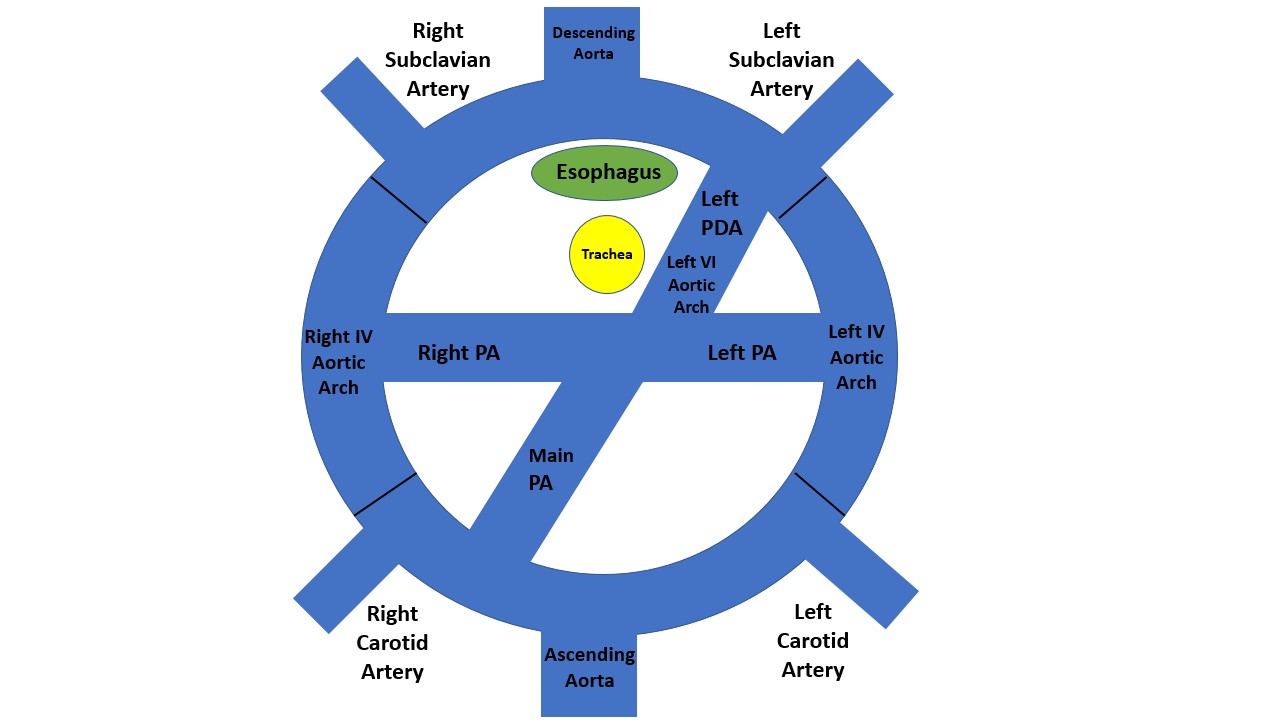

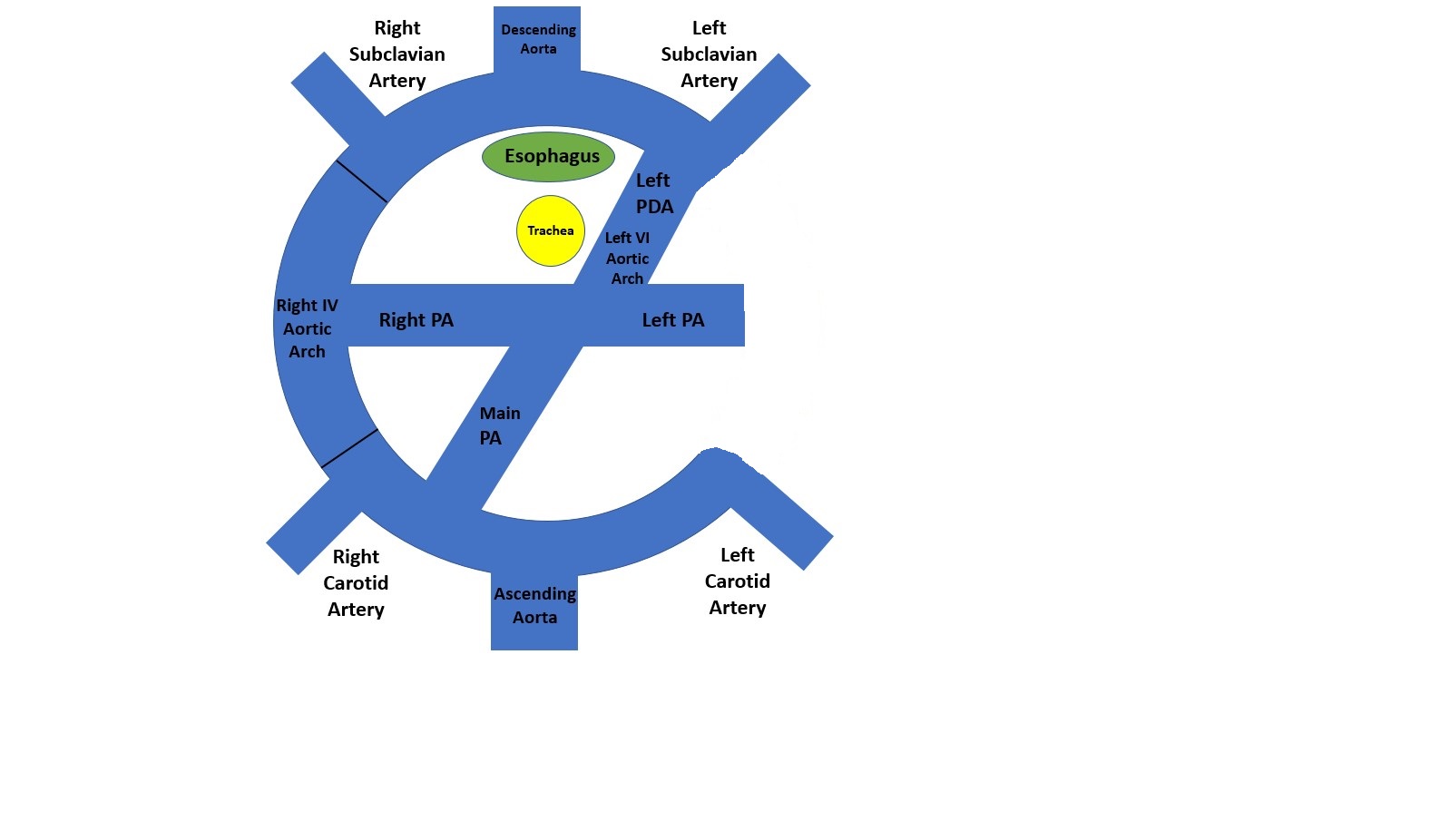

The first diagram below is a caudad view (looking from top to bottom) through a cartoon of a toti-potential arch. This arch DAA with bilateral ductus arteriosi was identified in 1 patient with transposition.[8] It has both arches and bilateral ductus arteriosi. As far as we can tell, there has not been a DAA with bilateral ductus arteriosi with a normal heart. The second diagram is the usual 1 from a person with a double aortic arch; however, there is usually a left ductus or ligamentum. It is rare for the DAA to have a right ductus or ligamentum. The final diagram is a right aortic arch with an aberrant (retro esophageal) left subclavian artery. With this, the IV aortic arch on the left is a regression. The first vessel from the ascending aorta is a left carotid artery; next, a right carotid artery, then a right subclavian artery, and finally, the aberrant (retro esophageal) left subclavian artery. The part between the left subclavian artery and the descending aorta is the diverticulum of Komerell.

Epidemiology

A double aortic arch is rare. whereas the incidence of RAA in the general population is more common at 0.1%.[9] In 1 of the studies, DAA is the most common cause of vascular ring, accounting for 55% of the cases, whereas RAA with aberrant left subclavian artery is 45%.[10] The incidence of DAA in 22q11 deletion is 14%, in which 17% are right arch dominant, whereas the incidence of RAA in 22q11 deletion is 30%.[6] There is a male predominance, with around 67% of the cases being male in 1 of the studies.[7]

Kommerell Diverticulum can have possible 2 scenarios: left aortic arch with aberrant right subclavian artery seen in 0.5% to 2% of the population.[4] The second 1 can be the right aortic arch with an aberrant left subclavian artery seen in 0.05% to 0.1% of the population.[4]

Pathophysiology

The ascending aorta further divides into right and left transverse arches in DAA. The right transverse arch courses over the right mainstem bronchus, whereas the left aortic arch is over the left. Because the aorta usually descends towards the left side of the body, the right aortic arch goes posteriorly and inserts into it. Further branches originate from the transverse arches: the left common carotid and subclavian from the left aortic arch and the right common carotid and right subclavian from the right arch. The arterial duct is usually left-sided and generally inserts in the left transverse arch or descending aorta.

The vascular ring is formed when there is a failure of the regression or persistence of some part of the aortic arch.[11] A double aortic arch is formed when both the fourth aortic arches persist. The ascending aorta and transverse aortic arch compress the trachea, whereas the right aortic arch compresses the esophagus. The right arch is dominant in three-fourths of patients with a double aortic arch.[10] Double aortic arch is sometimes associated with other congenital heart defects, including ventricular septal defects in about 10% of the patients, atrial septal defects in about 5% of the patients, tetralogy of Fallot in about 4% of the patients, and rare cases with truncus and transposition of the great vessels.[12][13][7]

History and Physical

Many patients with DAA have earlier presentations as compared to patients with other types of Vascular rings, most of them presenting in early infancy and almost all of them before 3 years of age.[7][10] The most common presentation is respiratory, seen in around 91% of the patients, and includes symptoms of stridor, wheezing, coughing, or choking.[7] Around 40% of patients presented with gastrointestinal symptoms like choking with feeds, dysphagia, and failure to thrive.[7] About 30% of the patients presented with cardiac symptoms like a murmur, cyanosis, or chest pain.[7]

In patients with an RAA with aberrant (retro-esophageal) left subclavian artery, it is considered a "looser ring" than a DAA. These patients usually have more problems with dysphagia. When they are babies, they can take milk easily. However, once they start taking solid foods, that is when the symptoms arrive. Many of these patients are not diagnosed until the teenage years when the guardians complain that the patient is the last to leave the dinner table. This is because the patient is chewing their food so that they can swallow without it hurting. Most do not realize that they are doing that.[14]

Evaluation

Prenatally, the diagnosis can be confirmed with a fetal echocardiogram.[15] Postnatally, other than confirming a suspected diagnosis, the purpose of testing is for side determination.[7][16] This would be beneficial to decide whether to perform a thoracotomy from either the left or right side.[7][16] The initial evaluation is generally done using a chest radiograph, showing narrow airways in 47% of patients and the dominant right arch in 40%.[7] Esophagography or barium swallow can be done, which shows a posterior indentation of the esophagus in around 74% of the patients.[7] CT and MRI are 100% sensitive for diagnosing DAA. MRI has replaced CT angiogram and cardiac catheterization for superior diagnosis and noninvasive technique in older children. The risk of general anesthesia for a child or infant who cannot breath-hold needs to be weighed against the radiation from a CT scan, which can be accomplished in seconds. Many modern CT scans use less radiation than prior CT scans, and the CT scan is better at delineating the tracheobronchial tree.[14][7][17] Echocardiography with Doppler and color mapping is noninvasive and convenient.[7] The echocardiogram can also evaluate any additional cardiac pathology before surgery.[18]

Treatment / Management

Most patients need surgical intervention, which is earlier in cases of DAA, around 1.4 months after the presentation and 4.9 months after being symptomatic. The operation site depends on the non-dominant arch, which is generally left-sided in around 71% of the patients. So, lateral thoracotomy via the left side is usually performed.[7] This is followed by ligating and dividing the small arch and then ligating and dividing the ductus arteriosus or ligament arteriosus.[19] The complete mobilization of the trachea and esophagus then accompanies this.[19] Many surgeons resect the diverticulum for patients with a Kommerell diverticulum and reimplant the left subclavian artery, end to side, with the left common carotid artery.[14] Alternatively, there is a minimally invasive surgery using video-assisted thoracoscopic techniques division of vascular ring, which seems safe and effective in children.[20](B2)

Differential Diagnosis

The vascular ring should be differentiated from conditions that can present with similar complaints. These include congenital tracheal anomalies like tracheoesophageal fistula or tracheomalacia. It can also present congenital laryngeal problems such as laryngomalacia, laryngeal webs or cysts, or external compression of the trachea with a mass like a lymphoma. Other things to remember are common conditions like asthma, gastro-esophageal reflux, or recurrent pneumonia.[21]

Prognosis

The prognosis is excellent, with about 26 of 300 patients needing reoperation.[22] There was no early or late mortality in many series, and some had 1 death.[23][22][24][25]

Complications

Postoperative complications are uncommon: chylothorax in 9% of the patients, transient hypertension in 4%, and vocal cord paralysis/paresis in 3% of patients.[7] There have been some cases of aortoesophageal fistula in 1 study.[26] The presentation of these patients was with copious gastrointestinal bleeding, which was relieved with an esophageal balloon catheter waiting for surgery.[26] Many patients still have problems with stridor after the operations for a while. This is because the trachea could not develop appropriately in utero or post-natally. It takes time for the patient to develop a stronger trachea and sometimes may even require an additional intervention to elevate the aorta off of the trachea.[22]

Deterrence and Patient Education

The median time between surgery and discharge from the ICU was 2 days, whereas discharge from the hospital was 5 to 8 days.[14][7] Most patients remain asymptomatic after surgery in 1 of the studies.[27] Whereas most studies have shown that respiratory symptoms were these patients' most common chronic symptoms.[7][28][29] The continued presence of symptoms has been related to tracheomalacia and tracheostenosis, generally due to the anomalous development of the trachea.[30]

Pearls and Other Issues

Double aortic arch presents at a younger age than RAA with aberrant (retro esophageal) left subclavian artery. However, most infants fully recover without complications.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The vascular ring is an uncommon diagnosis. DAA is an important cause of vascular rings, which generally causes symptoms in the newborn age group. Although cardiologists generally diagnose the condition, it is first seen by the neonatologist as soon as the baby is born. The clinicians are a vital part of the group who help diagnose the condition based on the vital signs and respiratory and feeding difficulties. Radiologist plays a very important part in diagnosing the condition. The pharmacist is also a crucial part of the team, as the baby would need to be given nothing by mouth and adequate fluids to be given by the venous route when planning for surgery. Ultimately, the surgeon is the 1 who would perform the surgery based on the information from all the team members.

A critical part of post-surgery care is the intensivist, who takes care of the patient and then transfers to the pediatrician, who then follows the patient for any complications. There is definitive evidence to recommend the type of imaging and treatment.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Backer CL, Mavroudis C. Congenital Heart Surgery Nomenclature and Database Project: vascular rings, tracheal stenosis, pectus excavatum. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2000 Apr:69(4 Suppl):S308-18 [PubMed PMID: 10798437]

Kellenberger CJ. Aortic arch malformations. Pediatric radiology. 2010 Jun:40(6):876-84. doi: 10.1007/s00247-010-1607-9. Epub 2010 Mar 31 [PubMed PMID: 20354848]

Licari A, Manca E, Rispoli GA, Mannarino S, Pelizzo G, Marseglia GL. Congenital vascular rings: a clinical challenge for the pediatrician. Pediatric pulmonology. 2015 May:50(5):511-24. doi: 10.1002/ppul.23152. Epub 2015 Jan 20 [PubMed PMID: 25604054]

Türkvatan A, Büyükbayraktar FG, Olçer T, Cumhur T. Multidetector computed tomographic angiography of aberrant subclavian arteries. Vascular medicine (London, England). 2009 Feb:14(1):5-11. doi: 10.1177/1358863X08097903. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19144774]

Tanaka A, Milner R, Ota T. Kommerell's diverticulum in the current era: a comprehensive review. General thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2015 May:63(5):245-59. doi: 10.1007/s11748-015-0521-3. Epub 2015 Jan 31 [PubMed PMID: 25636900]

McElhinney DB, Clark BJ 3rd, Weinberg PM, Kenton ML, McDonald-McGinn D, Driscoll DA, Zackai EH, Goldmuntz E. Association of chromosome 22q11 deletion with isolated anomalies of aortic arch laterality and branching. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2001 Jun 15:37(8):2114-9 [PubMed PMID: 11419896]

Alsenaidi K, Gurofsky R, Karamlou T, Williams WG, McCrindle BW. Management and outcomes of double aortic arch in 81 patients. Pediatrics. 2006 Nov:118(5):e1336-41 [PubMed PMID: 17000782]

Shirali GS, Geva T, Ott DA, Bricker JT. Double aortic arch and bilateral patent ducti arteriosi associated with transposition of the great arteries: missing clinical link in an embryologic theory. American heart journal. 1994 Feb:127(2):451-3 [PubMed PMID: 8296720]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHastreiter AR, D'Cruz IA, Cantez T, Namin EP, Licata R. Right-sided aorta. I. Occurrence of right aortic arch in various types of congenital heart disease. II. Right aortic arch, right descending aorta, and associated anomalies. British heart journal. 1966 Nov:28(6):722-39 [PubMed PMID: 5332779]

Lowe GM, Donaldson JS, Backer CL. Vascular rings: 10-year review of imaging. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 1991 Jul:11(4):637-46 [PubMed PMID: 1887119]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceEDWARDS JE. Anomalies of the derivatives of the aortic arch system. The Medical clinics of North America. 1948 Jul:32():925-49 [PubMed PMID: 18877614]

Cui W, Patel D, Husayni TS, Roberson DA. Double aortic arch and d-transposition of the great arteries. Echocardiography (Mount Kisco, N.Y.). 2008 Jan:25(1):91-5. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2007.00554.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18186786]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYıldırım SV, Yıldırım A. Truncus arteriosus with double aortic arch: A rare association. The Turkish journal of pediatrics. 2017:59(2):221-223. doi: 10.24953/turkjped.2017.02.020. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29276881]

Backer CL, Mongé MC, Popescu AR, Eltayeb OM, Rastatter JC, Rigsby CK. Vascular rings. Seminars in pediatric surgery. 2016 Jun:25(3):165-75. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2016.02.009. Epub 2016 Feb 22 [PubMed PMID: 27301603]

Hunter L, Callaghan N, Patel K, Rinaldi L, Bellsham-Revell H, Sharland G. Prenatal echocardiographic diagnosis of double aortic arch. Ultrasound in obstetrics & gynecology : the official journal of the International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2015 Apr:45(4):483-5. doi: 10.1002/uog.13408. Epub 2015 Mar 9 [PubMed PMID: 24817195]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCantinotti M, Hegde S, Bell A, Razavi R. Diagnostic role of magnetic resonance imaging in identifying aortic arch anomalies. Congenital heart disease. 2008 Mar-Apr:3(2):117-23. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0803.2008.00174.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18380760]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBisset GS 3rd, Strife JL, Kirks DR, Bailey WW. Vascular rings: MR imaging. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 1987 Aug:149(2):251-6 [PubMed PMID: 3496746]

Lillehei CW, Colan S. Echocardiography in the preoperative evaluation of vascular rings. Journal of pediatric surgery. 1992 Aug:27(8):1118-20; discussion 1120-1 [PubMed PMID: 1403546]

Wychulis AR, Kincaid OW, Weidman WH, Danielson GK. Congenital vascular ring: surgical considerations and results of operation. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 1971 Mar:46(3):182-8 [PubMed PMID: 5553129]

Koontz CS, Bhatia A, Forbess J, Wulkan ML. Video-assisted thoracoscopic division of vascular rings in pediatric patients. The American surgeon. 2005 Apr:71(4):289-91 [PubMed PMID: 15943400]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceShah RK, Mora BN, Bacha E, Sena LM, Buonomo C, Del Nido P, Rahbar R. The presentation and management of vascular rings: an otolaryngology perspective. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2007 Jan:71(1):57-62 [PubMed PMID: 17034866]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBacker CL, Mongé MC, Russell HM, Popescu AR, Rastatter JC, Costello JM. Reoperation after vascular ring repair. Seminars in thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. Pediatric cardiac surgery annual. 2014:17(1):48-55. doi: 10.1053/j.pcsu.2014.01.001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24725717]

Schmidt AMS, Larsen SH, Hjortdal VE. Vascular ring: Early and long-term mortality and morbidity after surgical repair. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2018 Oct:53(10):1976-1979. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2017.12.022. Epub 2018 Jan 3 [PubMed PMID: 29402450]

Saran N, Dearani J, Said S, Fatima B, Schaff H, Bower T, Pochettino A. Vascular Rings in Adults: Outcome of Surgical Management. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2019 Oct:108(4):1217-1227. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2019.04.097. Epub 2019 Jun 20 [PubMed PMID: 31229482]

Tola H, Ozturk E, Yildiz O, Erek E, Haydin S, Turkvatan A, Ergul Y, Guzeltas A, Bakir I. Assessment of children with vascular ring. Pediatrics international : official journal of the Japan Pediatric Society. 2017 Feb:59(2):134-140. doi: 10.1111/ped.13101. Epub 2016 Oct 31 [PubMed PMID: 27454661]

Othersen HB Jr, Khalil B, Zellner J, Sade R, Handy J, Tagge EP, Smith CD. Aortoesophageal fistula and double aortic arch: two important points in management. Journal of pediatric surgery. 1996 Apr:31(4):594-5 [PubMed PMID: 8801321]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencevan Son JA, Julsrud PR, Hagler DJ, Sim EK, Pairolero PC, Puga FJ, Schaff HV, Danielson GK. Surgical treatment of vascular rings: the Mayo Clinic experience. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 1993 Nov:68(11):1056-63 [PubMed PMID: 8231269]

Anand R, Dooley KJ, Williams WH, Vincent RN. Follow-up of surgical correction of vascular anomalies causing tracheobronchial compression. Pediatric cardiology. 1994 Mar-Apr:15(2):58-61 [PubMed PMID: 7997414]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceChun K, Colombani PM, Dudgeon DL, Haller JA Jr. Diagnosis and management of congenital vascular rings: a 22-year experience. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 1992 Apr:53(4):597-602; discussion 602-3 [PubMed PMID: 1554267]

Fleck RJ, Pacharn P, Fricke BL, Ziegler MA, Cotton RT, Donnelly LF. Imaging findings in pediatric patients with persistent airway symptoms after surgery for double aortic arch. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2002 May:178(5):1275-9 [PubMed PMID: 11959745]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence