Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Vastus Lateralis Muscle

Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Vastus Lateralis Muscle

Introduction

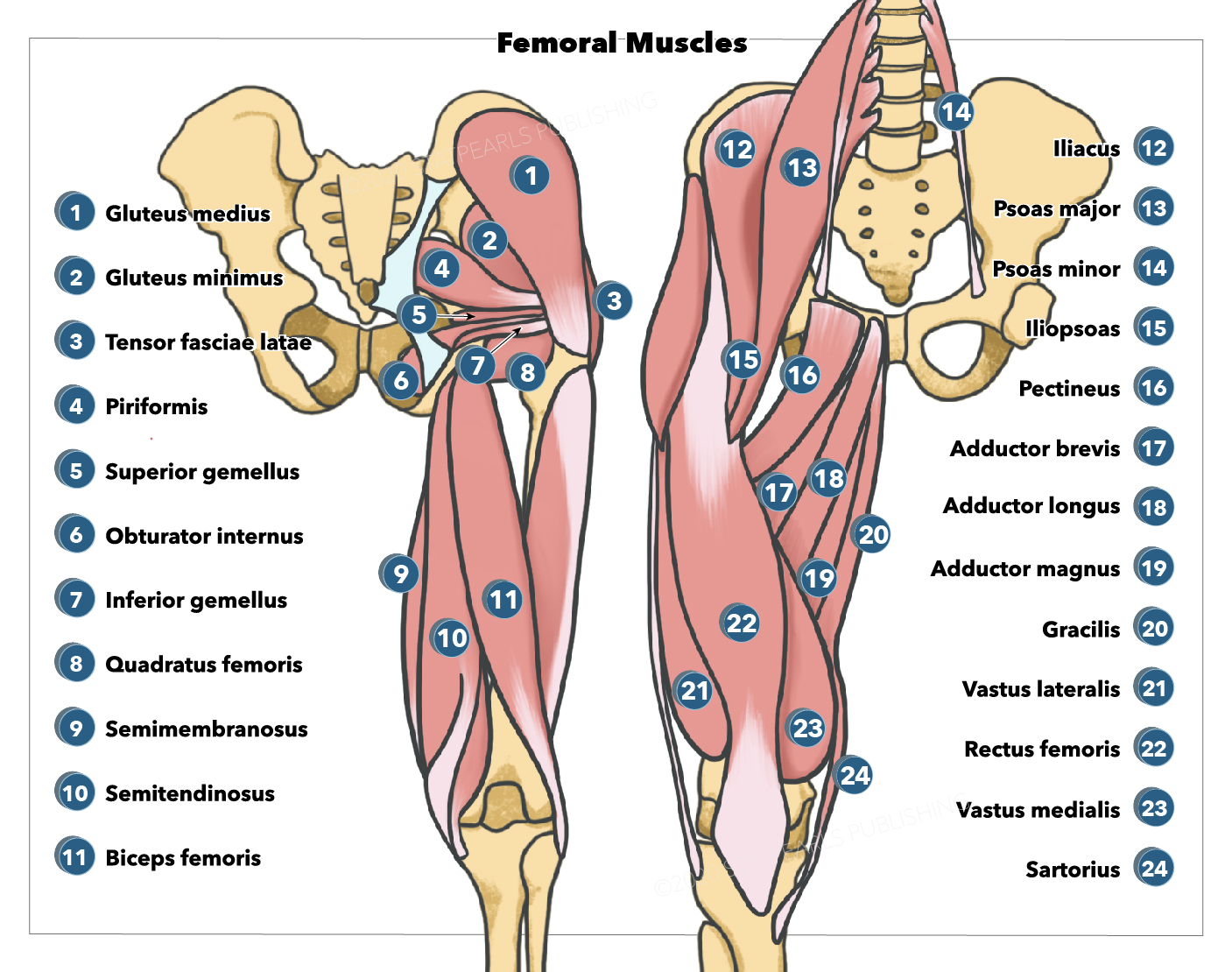

The vastus lateralis (VL) is a unipennate muscle and a member of the anterior compartment of the thigh along with the sartorius, quadriceps femoris, rectus femoris (RF), vastus medialis (VM), and vastus intermedius (VI) muscles. The VL is 1 of the 4 component muscles of the quadriceps muscle group: rector femoris, vastus lateralis, vastus medialis, and vastus intermedius. The vastus lateralis is the largest component of the quadriceps muscle groups and is positioned laterally about the femur.[1][2]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The VL has a broad, continuous origination about the proximal femur. Origin points include the intertrochanteric line, greater trochanter, lateral aspect of the linea aspera, gluteal tuberosity, and the lateral intermuscular septum. The fibers of this muscle converge and contribute to the quadriceps tendon, insert on the lateral aspect of the patella, and terminally insert on the tibial tuberosity via the patellar tendon.

The VL is enclosed by a strong fascial layer known as the fascia lata. The fascia lata thickens laterally as it blends into the iliotibial tract. The intermuscular septae that divide the thigh into anterior, medial, and lateral compartments receive their fibrous division from the deep aspect of the fascia lata. The lateral intermuscular septum is much stronger than the other two and separates the VL and VI of the anterior compartment from the short and long heads of the biceps femoris and the posterior compartment. The lateral intermuscular septum between the anterior and posterior compartments forms an inter-nervous plane which may be used as an important intraoperative landmark.

Anatomically, the VL is bordered laterally by subcutaneous tissue, and medially, it is bordered by the femur and the VI at the level of the greater trochanter. The RF forms the anteromedial border while the posteromedial aspect of the VL is bordered by the intermuscular septum, sciatic nerve, and biceps femoris muscle at the level of the greater trochanter.

Functionally, the vastus lateralis functions as a primary extender of the knee. In conjunction with the VM, the VL stabilizes the knee joint. The VL is part of the intermediate layer of the quadriceps tendon. The other part of the intermediate layer is the VM. These 2 muscles fuse to form a continuous aponeurosis that inserts on the base of the patella. Reflections of the aponeurosis extend laterally and medially to insert on the sides of the patella. Laterally, the VL ends in an aponeurosis that blends with the lateral patella or RF tendon, and distally, the fibers of the vastus lateralis combine with the vastus medialis fibers to form the retinacular ligament of the knee, which inserts on the tibial condyles and ultimately forms the anterior capsule of the knee. This patellar retinaculum helps keep the patella aligned over the femur.[2]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The lateral circumflex femoral artery primarily supplies the vastus lateralis. The lateral circumflex femoral artery has three main branches: ascending, transverse, and descending. The muscle also receives some blood supply from perforating arteries of the deep artery of the thigh, also known as the profunda femoris. The perforating arteries pierce the lateral intermuscular septum to gain access to the anterior compartment of the thigh. The parent artery arises from the lateral or posterior side of the femoral artery in the femoral triangle.

Venous drainage of the VL is achieved through the perforating veins of the deep femoral vein, the lateral femoral circumflex vein, and other unnamed veins from the superficial venous circulation. Larger named veins in the area that assist with drainage are named akin to the corresponding artery.[2]

Nerves

The VL is innervated by penetrating muscular branches of the femoral nerve. The nerve roots involved include L2, L3, and L4. The predominant nerve root responsible for VL action is L3.[2]

Physiologic Variants

The VL may have two insertional heads in approximately 60% of specimens. These two heads are referred to as the vastus lateralis long head (VLL) and the vastus lateralis obliquus (VLO).[3] A layer of fat or fascia achieves this separation from the longitudinal head in most specimens. Variations in origin and insertion sites were uncommon.[4] If the VLO is present, the angulation of fiber insertion on the patella shows distinct variation from specimen to specimen. The VLL typically inserts at an angle between 10 degrees and 17 degrees +/- 8 degrees. The VLO, however, has an insertional variation between 26 degrees and 41 degrees.[5]

Surgical Considerations

The blood supply for the VL is primarily the lateral circumflex femoral artery, as stated above. This main arterial supply enters the muscle anteriorly. The three branches of this vessel are anatomic landmarks in many orthopedic approaches to the hip. The ascending branch requires ligation during the anterior approach. The descending branch is in the plane between the VI and the VL and is often encountered during the anterolateral approach to the thigh.

Due to its extensive origin on the femur, the VL plays a key role as a landmark in many operative procedures involving both the femur and the hip joint. For any repair of the femoral shaft or proximal femoral replacement, the VL must be reflected to provide visualization of the femur.

In the lateral approach (Hardinge) to the hip, an internervous interval is created between the gluteus medius innervated by the superior gluteal nerve and the VL innervated by the femoral nerve. This interval is achieved by splitting the VL during the dissection. The VL is identified once the dissection has been carried through the fascia lata. In this approach, the lateral circumflex artery is at risk for damage.[6] During the posterolateral and direct posterior approaches to the thigh, similar internervous planes are created. The intervals are between the femoral nerve and the sciatic nerves. In the posterolateral approach, the interval divides the VL (femoral nerve) and the hamstring muscle group (sciatic nerve). In the direct posterior approach, the interval is between the VL and the biceps femoris (sciatic nerve).

The VLO is also a landmark used in the placement of portals during knee arthroscopy. If a superolateral inflow portal is to be used during an arthroscopic knee procedure, the portal is placed lateral to the body of the VLO.

Clinical Significance

As part of the quadriceps muscle group, the VL contracts during the termination of the swing phase of gait to prepare the knee for weight-bearing, the muscle group as a whole is responsible for absorbing the vast majority of the force generated by the heel strike. The muscle group continues to contract through the early portion of the stance phase as part of the loading response. Lastly, as part of the quadriceps muscle group, the VL eccentrically contracts during downhill walking and descending steps.

The VL is the strongest member of the quadriceps muscle group, and thus it is one of the main contributors to anterior knee pain syndromes. The VL is estimated to contribute approximately 40% of the overall strength of the quadriceps muscle group, with RF and VI accounting for 35% and the VM totaling the last 25%.[7] Overdevelopment of the vastus lateralis has been attributed as a major cause of patellofemoral dysfunction in addition to a more proximal attachment of the vastus medialis obliquus (VMO). An imbalance between the VL and VM can result in abnormal patellar movement, pain, and joint instability. The patellar movement could be further abnormal depending on the Q-angle of the limb. In a genu valgum (increased Q-angle) lower extremity, the effect of the lateral pull of the patella by the VL will be exacerbated, creating an abnormal wear pattern and furthering arthritic processes.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

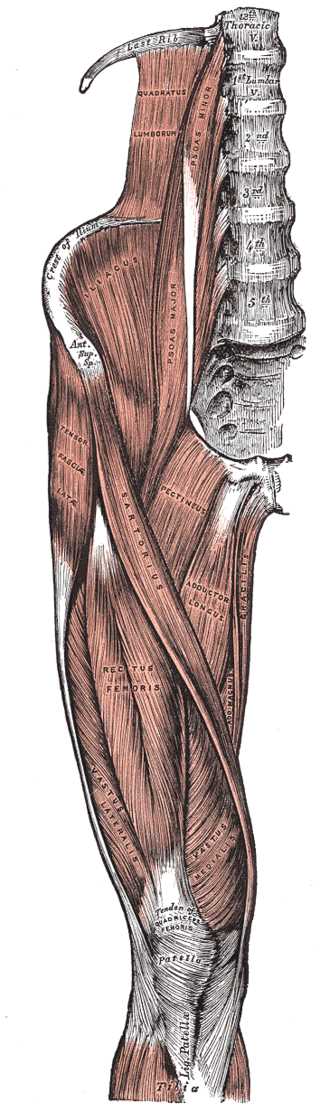

Right Hip and Femoral Muscles, Anterior View. This illustration shows the tensor fasciae latae, thoracic vertebrae, quadratus lumborum, psoas minor and major, crest of ilium, anterior superior iliac spine, iliacus, sartorius, pectineus, adductor longus, gracilis, adductor magnus, rectus femoris, vastus lateralis and medialis, tibia, patella, and quadriceps tendon.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

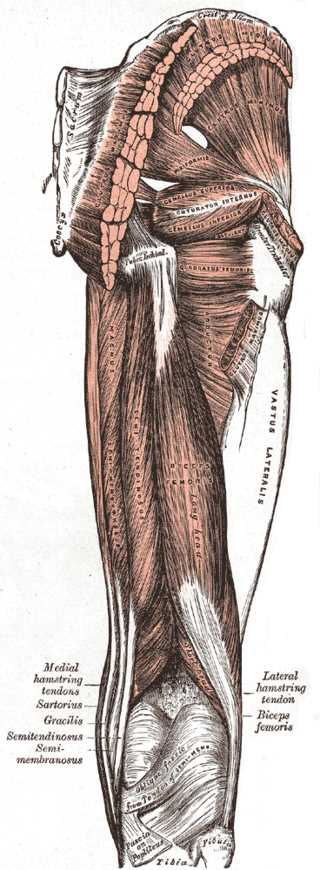

Muscles of the Hip and Thigh. The gluteal muscles include the gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, and gluteus minimus. Hip muscles include the piriformis, gemellus superior, gemellus inferior, and obturator internus. Thigh muscles include the adductor magnus, vastus lateralis, biceps femoris, semitendinosus, hamstring tendons, and gracilis.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Khan A, Arain A. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Anterior Thigh Muscles. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30860696]

Bordoni B, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Thigh Quadriceps Muscle. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30020706]

Horwath O, Envall H, Röja J, Emanuelsson EB, Sanz G, Ekblom B, Apró W, Moberg M. Variability in vastus lateralis fiber type distribution, fiber size, and myonuclear content along and between the legs. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985). 2021 Jul 1:131(1):158-173. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00053.2021. Epub 2021 May 20 [PubMed PMID: 34013752]

Waligora AC, Johanson NA, Hirsch BE. Clinical anatomy of the quadriceps femoris and extensor apparatus of the knee. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2009 Dec:467(12):3297-306. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1052-y. Epub 2009 Aug 19 [PubMed PMID: 19690926]

Weinstabl R, Scharf W, Firbas W. The extensor apparatus of the knee joint and its peripheral vasti: anatomic investigation and clinical relevance. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 1989:11(1):17-22 [PubMed PMID: 2497528]

Hardinge K. The direct lateral approach to the hip. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume. 1982:64(1):17-9 [PubMed PMID: 7068713]

Farahmand F, Senavongse W, Amis AA. Quantitative study of the quadriceps muscles and trochlear groove geometry related to instability of the patellofemoral joint. Journal of orthopaedic research : official publication of the Orthopaedic Research Society. 1998 Jan:16(1):136-43 [PubMed PMID: 9565086]