Introduction

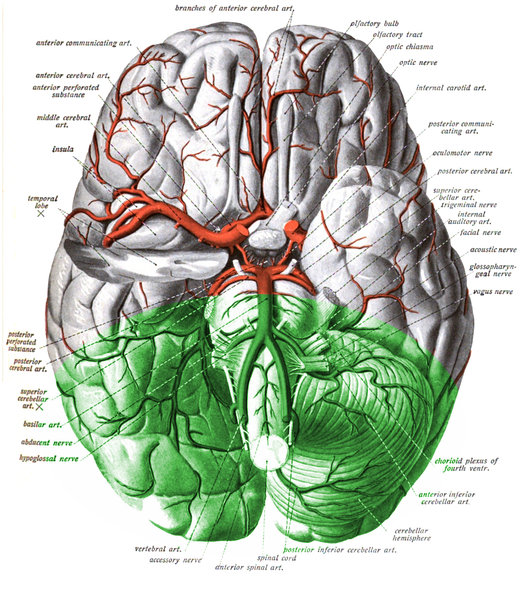

Vertebrobasilar insufficiency (VBI) is defined by inadequate blood flow through the posterior circulation of the brain, supplied by the 2 vertebral arteries that merge to form the basilar artery. The vertebrobasilar arteries supply the cerebellum, medulla, midbrain, and occipital cortex. When the blood supply to these areas is compromised, it can lead to severe disability and/or death. Because the cerebellum is involved, survivors are often left with dysfunction of many organs including ataxia, hemiplegia, gaze abnormalities, dysarthria, dysphagia and cranial nerve palsies. Fortunarely, many patients have small vessel involvement and thus the neurological deficits are mild and localized.

The term, VBI, was coined in the 1950s after C. Miller Fisher used carotid insufficiency to describe transient ischemic attacks (TIA) in the carotid supplied territories and is therefore often used to describe brief episodes of transient ischemic attacks in the vertebrobasilar territory. Also known as the posterior circulation, the vertebrobasilar vasculature supplies areas such as the brainstem, thalamus, hippocampus, cerebellum, occipital and medial temporal lobes. Although patients may initially be asymptomatic, the significant build-up of atherosclerotic plaques over time may lead to ischemic events. Stroke may occur either due to an occlusion of the vertebral or basilar artery or an embolus that that may lodge more proximal to the brain[1]. In the emergency setting, VBI is an important diagnosis to consider as many symptoms can appear like other benign etiologies such as labyrinthitis, vestibular neuritis, and benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV).

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Certain risk factors predispose patients to VBI, particularly those that exacerbate atherosclerosis. These risk factors include smoking, hypertension, age, gender, family history and genetics, and hyperlipidemia. Furthermore, patients with a history of coronary artery disease or peripheral artery disease are at increased risk [2]. The other etiological causes may include cardioembolic conditions such as atrial fibrillation, infective endocarditis, vertebral artery dissection, and systemic hypercoagulable states.

Epidemiology

About a quarter of strokes and TIAs occur in the vertebrobasilar distribution. Like the prevalence of atherosclerotic disease, vertebrobasilar disease occurs later in life, particularly around the 7 to 8 decades, with a predilection for the male gender. As many as 25% of the elderly population present with impaired balance and increased fall risks as a consequence of VBI. Similar to other types of stroke syndromes, African Americans are more prevalent than other ethnic groups due to multiple reasons including genetics, higher prevalence of hypertension and differences in healthcare delivery.

Pathophysiology

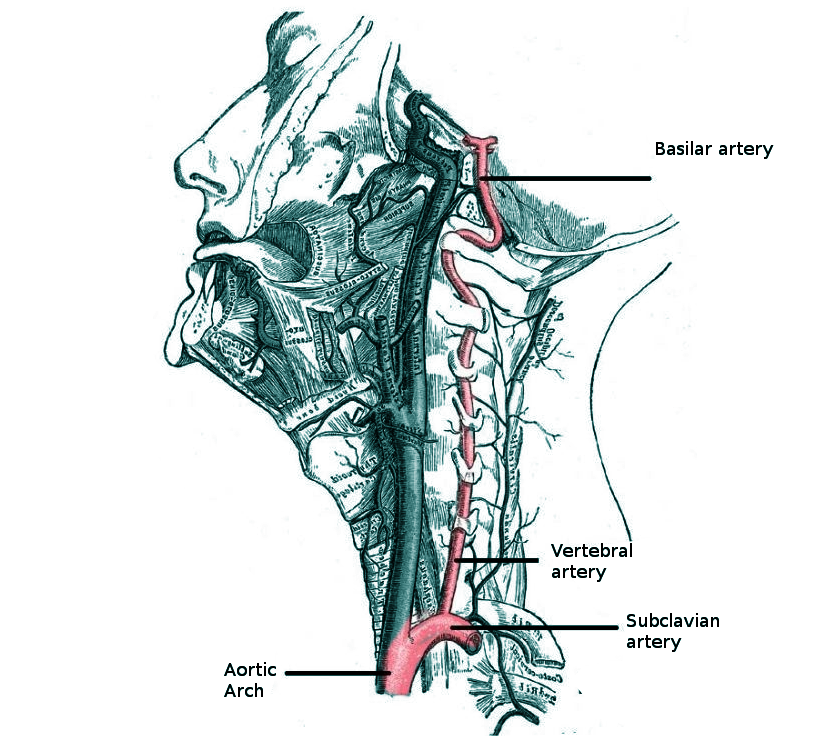

As with other types of strokes, infarct can occur from either an embolism, in-situ thrombosis, or lacunar disease secondary to chronic hypertension. Usually, VBI is caused by 2 processes of ischemia: hemodynamic insufficiency and embolism. Unlike the carotid arteries, embolism via the vertebral arteries is not common. Donor sites for embolism may include the aortic arch, the origin of the vertebral artery or the proximal subclavian arteries. Most cases, however, are due to atherosclerotic disease.

Hemodynamic

Decreased perfusion causes most VBI. Hemodynamic ischemia occurs to inadequate blood flow through the basilar artery, especially in the elderly and diabetic populations with poor sympathetic control. Symptoms tend to be reproducible and short, rarely causing infarction. For hemodynamic ischemia to occur, there must be occlusion in both vertebral arteries or within the basilar artery. Also, there must be an incomplete contribution by the carotid circulation via the posterior communicating artery in the circle of Willis. Other causes for a decrease in perfusion include antihypertensive medications, cardiac arrhythmia, pacemaker malfunction, and vasculitis. Thus, it is imperative that a complete workup, including ECG, be done to rule out cardiogenic causes. Occlusions in other blood vessels such as in Subclavian Steal syndrome may also cause VBI by “stealing” blood flow from the brainstem as blood flows down the path of least resistance via the vertebral artery in the presence of proximal stenosis/occlusion of the subclavian artery.

Embolism

VBI may also originate from atherosclerotic plaques that later break off to form emboli. However, emboli may also develop as a result of intimal defects secondary to trauma, compression, and in a minority of cases from fibromuscular dysplasia, aneurysm or dissection. Possibly up to one-third of cases occur intracranially, as distal emboli form from lesions within the subclavian, vertebral, or basilar artery. Most lesions that form extracranially arise from an atherosclerotic buildup in one of the vertebral arteries, and rarely the innominate or subclavian. In a very small number of cases, thrombi can arise from an ectatic or fusiform basilar artery aneurysm which may then embolize to more distal branches[3][4][5].

Toxicokinetics

Differentiating VBI from a hemispheric stroke

- Lesions as a result of VBI have certain clinical features that make it possible to differentiate them from hemispheric strokes:

- Cerebellar signs like ataxia and dysmetria are common

- If the cranial nerve is involved, the clinical signs are usually ipsilateral to the lesion and the corticospinal clinical features are seen in the opposite leg and arm, due to crossing.

- Dysphagia and dysarthria are common with VBI

- With brain stem lesions, unilateral Horner syndrome may be present

- Nausea, vertigo, nystagmus, and vomiting are common when the vestibular system is involved

- Involvement of the occipital lobe results in visuospatial or visual field defects

- In general, cognitive impairment and aphasia (cortical deficits) are absent

History and Physical

The most common findings in a patient’s history to suggest VBI include risk factors for cardiovascular diseases such as atherosclerosis and advanced age. A thorough history and physical exam should be completed, with special attention to not only the neurological but cardiac exam for conditions such as an arrhythmia which may cause the symptoms as well. Symptoms of VBI are a result of ischemia on the different parts of the brain supplied by the posterior circulation.

Symptoms include:

- Vertigo (the most common symptom)

- Dizziness/syncope: Sixty percent of patients with VBI have at least 1 episode of dizziness.

- "Drop attacks:" Patient feels suddenly weak in the knees and fall

- Diplopia/Loss of vision

- Paresthesia

- Confusion

- Dysphagia/dysarthria

- Headache

- Altered consciousness

- Ataxia

- contralateral motor weakness

- Loss of temperature and pain

- Incontinence

If VBI advances into a brainstem infarction, several syndromes may arise depending on the location such as lateral medullary syndrome, medial medullary syndrome, basilar artery syndrome, and Labyrinthine artery occlusion. Other aspects of the history which should be noted during the physical exam are reproducible symptoms during positional head changes, i.e., syncope while turning the head laterally (Bow Hunter syndrome) or during head extension [6][7][8].

Physical exam

Findings are common following a vertebral artery stroke and can include the following:

- Change in level of consciousness

- Hemiparesis

- Alteration in pupil size and reactivity

- Cranial nerve palsies (usually abducens nerve palsy)

- Ocular bobbing

- Vertical gaze palsy (CN lll lesion)

- Horizontal gaze palsy (CN 6 lesion

- Facial nerve paralysis

- Bulbar palsy ( dysarthria, dysphonia, dysphagia, dysarthria, facial weakness)

- Contrateralhemianopia with macular sparing (posterior cerebral artery involvement)

- Ipsilateral temperature loss and facial pain, Horner syndrome (part of medullary syndrome)

Care must be taken to rule out other more benign conditions that may also cause similar symptoms such as labyrinthitis, vestibular neuritis, and benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV). Vertigo is a common symptom in VBI. It is also a central symptom of peripheral vestibular disorders which are more benign. It is especially important in the emergency department setting to differentiate between vertigo due to peripheral vestibular disorders and central vestibular problems most commonly due to vertebrobasilar insufficiency (VBI) which may require hospitalization. Vertigo by itself cannot be diagnosed as TIA or VBI. Vertigo in the presence of brainstem signs or symptoms will be diagnostic of vertebrobasilar territory TIA. Physical examination to look for brainstem signs or cranial nerve abnormalities is very important. Presence of contralateral extremity signs or symptoms is helpful. The type of nystagmus such as vertical nystagmus or direction-changing nystagmus is indicative of VBI. The head thrust test if performed and interpreted properly may differentiate peripheral vertigo from central vertigo due to VBI at the bedside. A positive head thrust test is indicative of a peripheral cause of vertigo.

Vertebral artery stroke is associated with a variety of syndromes depending on the clinical features. Some of these syndromes include:

- Locked in syndrome

- Lateral medullary syndrome

- Internuclear ophthalmoplegia

- Cerebellar infarction

- Medial medullary syndrome

- Posterior cerebral artery occlusion

Evaluation

Imaging of the vertebral and basilar arteries via arteriography is important for the diagnosis and management. Noninvasive CTA or MRA is commonly used to visualize the vertebral-basilar system to define stenosis or occlusions. CTA will produce good images both intracranial and extracranial vessels [9]. The extracranial vessel may require contrast-enhanced MRA due to swallowing artifacts. For CTA caution must be taken into consideration given the nephrotoxicity of the contrast and radiation exposure. In the presence of an impaired renal function, gadolinium MR contrast may also result in the rare complication of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF), also known as nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy (NFD). MRI is always a better imaging modality for brainstem and posterior fossa problems especially acute brainstem infarction with diffusion-weighted imaging.

Other pathology such as brainstem cavernoma or cerebellopontine angle lesions including acoustic schwannoma and dermoid/epidermoid cysts, which may be identified by MRI convincingly. Duplex ultrasound may also be used for abnormalities within the vertebral artery, albeit its limitations. Although difficult to visualize V1 and V2, duplex ultrasound may detect changes in flow velocity from proximal vertebral stenosis or subclavian steal. For patients who are older than the age of 45, workup should include identifying risk factors that may cause VBI such as cholesterol levels, lipids, blood sugar, blood pressure, and smoking cessation. If a patient is younger than 45 years old, further workup is indicated to rule out the cardioembolic cause, hypercoagulable states, vertebral dissection, and fibromuscular dysplasia.

Blood work should involve a complete CBC, electrolytes, renal function, coagulation profile, lipid profile, and liver function. In younger patients, one should also investigate for lupus anticoagulant, Protein C, S and factor V Leiden mutation.

ECG may reveal ischemic changes, arrhythmias (atrial fibrillation) or an MI.

Young patients should also undergo an echocardiogram to rule of vegetations, valvular defects, right to left shunts or thrombi.

Treatment / Management

As with ischemic strokes in the anterior circulation, treatment of vertebrobasilar disease requires prompt management. Previous transient episodes (TIAs) can signal the onset of an infarct in the future. If the cause of embolism is determined to be cardiogenic, most likely due to atrial fibrillation or mechanical heart valves, then anticoagulation therapy is indicated. Although not as common, vertebral dissection secondary to trauma may also be the source of embolism, managed again with antithrombotic. Otherwise, treatment depends on reducing risk factors such as smoking, cholesterol, and hypertension. In the acute setting, the symptoms are often pressure/perfusion dependent. Perfusion may need to be augmented by IV fluid and attempt to avoid lowering the blood pressure. In the longer term, stricter blood pressure control is important in secondary stroke prevention. Similar to all types of ischemic events, secondary prevention will require a multimodality approach including BP control, quitting smoking, strict blood sugar control, use of a statin, lifestyle changes including diet and exercises [10]. Surgical options are very limited [11]. It depends on the location of the plaque and the efficacy of repair. The more distal the occlusion from the brain the more likely to consider surgery as an option [12]. The criteria for surgery depends on:(A1)

- Bilaterally significant VA stenosis, i.e., greater than 60% stenosis IN BOTH arteries. Or greater than 60% stenosis in the dominant vertebral artery (VA) if contralateral is hypoplastic, ends in the posterior inferior cerebellar artery (PICA), or is occluded.

- Symptomatic embolism believed to originate from a vertebral lesion

- Symptomatic repair of an aneurysm or if an aneurysm is greater than 1.5 cm regardless of symptoms.

There are 2 options for surgical repair: open surgical repair and endovascular treatment. Open surgical repair involves a bypass graft over the stenosed area. Direct arterial transposition places the artery to a nearby healthy vessel and joining the 2 parts [13]. The most common procedure is endovascular repair, which involves placing a stent via a catheter in the groin. A balloon is then placed within the stenotic vertebral artery with eventual stent placement [14].

All patients with a vertebral artery stroke should be admitted to the ICU especially is they are hemodynamically unstable, have fluctuating neurological symptoms, have other comorbidity and are candidates for thrombolytic therapy.

Once the patient has been stabilized, the decision to treat depends on the duration of symptoms. If patients present within 4.5 hours of symptoms, tPA is effective. Anticoagulation may be used but there is no evidence that it may improve outcomes.

Angioplasty is often performed for patients with basilar artery stenosis but its role in vertebral artery stroke remains undefined.

Differential Diagnosis

- Benign positional vertigo in emergency medicine

- Labyrinthitis

- MELAS(mitochondrial encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes)

- Multiple sclerosis

- Posterior fossa tumour

- Subclavian steal syndrome

- Stroke haemorrhage

- Stroke ischemic

- Transient ischemic attack

- Transtentorial herniation

- Vertebral artery dissection

- Vasculitis

- Vestibular neuronitis

Prognosis

The prognosis following a vertebral artery stroke depends on the severity, patient age, and other comorbidities. There is also a 10-15% risk of recurrence. Even with a minor stroke, the morbidity is high. Patients who survive often need extensive rehabilitation for many months and even then residual neurological deficits may be present.

Complications

- Deep vein thrombosis

- Aspiration pneumonia

- MI

- Pulmonary embolism

- Pressure sores

- Gastritis

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Vertebrobasilar insufficiency is managed by an interprofessional team that includes the emergency department physician, neurologist, radiologist, internist, and a stroke specialist. Most patients become disabled and recovery for the survivors can take years.

While the definitive treatment is under the care of a neurologist, the primary care provider and nurse practitioner should educate the patients on preventing further episodes. Following a vertebral artery stroke, most patients have significant disability and recovery is prolonged. These patients require extensive rehabilitation to improve speech, swallowing, and gait. In addition, many nursing issues have to be addressed including bowel and bladder training, nutrition, patient safety, prevention of pressure ulcers and performing daily living activities.

In addition, patients often become depressed and a consult from a mental health nurse is highly recommended.

The patient should be discouraged from smoking, remain compliant with medications, maintain a healthy weight, ensure that the cholesterol levels are under control and participate in regular exercise. Because of the risk of a recurrent stroke, follow up is vital. Those who are maintained on warfarin need to have their INR checked regularly.

Speech, occupational, and physical therapy are an integral part of treatment and most patients need extensive rehabilitation for many months. A home care nurse is often needed to check on patient recovery and progress. The entire team must communicate to ensure that the patient is receiving the optimal standard of care.

The outcomes for patients with vertebrobasilar insufficiency depends on the severity of the stroke, age, comorbidity, and degree of neurological deficit.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Caplan L, Chung CS, Wityk R, Glass T, Tapia J, Pazdera L, Chang HM, Dashe J, Chaves C, Vemmos K, Leary M, Dewitt L, Pessin M. New England medical center posterior circulation stroke registry: I. Methods, data base, distribution of brain lesions, stroke mechanisms, and outcomes. Journal of clinical neurology (Seoul, Korea). 2005 Apr:1(1):14-30. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2005.1.1.14. Epub 2005 Apr 30 [PubMed PMID: 20396469]

Lima Neto AC, Bittar R, Gattas GS, Bor-Seng-Shu E, Oliveira ML, Monsanto RDC, Bittar LF. Pathophysiology and Diagnosis of Vertebrobasilar Insufficiency: A Review of the Literature. International archives of otorhinolaryngology. 2017 Jul:21(3):302-307. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1593448. Epub 2016 Oct 26 [PubMed PMID: 28680502]

Najafi MR, Toghianifar N, Abdar Esfahani M, Najafi MA, Mollakouchakian MJ. Dolichoectasia in vertebrobasilar arteries presented as transient ischemic attacks: A case report. ARYA atherosclerosis. 2016 Jan:12(1):55-8 [PubMed PMID: 27114738]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYuh SJ, Alkherayf F, Lesiuk H. Dolichoectasia of the vertebral basilar and internal carotid arteries: A case report and literature review. Surgical neurology international. 2013:4():153. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.122397. Epub 2013 Nov 29 [PubMed PMID: 24381796]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLou M, Caplan LR. Vertebrobasilar dilatative arteriopathy (dolichoectasia). Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2010 Jan:1184():121-33. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05114.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20146694]

Go G, Hwang SH, Park IS, Park H. Rotational Vertebral Artery Compression : Bow Hunter's Syndrome. Journal of Korean Neurosurgical Society. 2013 Sep:54(3):243-5. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2013.54.3.243. Epub 2013 Sep 30 [PubMed PMID: 24278656]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYang YJ, Chien YY, Cheng WC. Vertebrobasilar insufficiency related to cervical spondylosis. A case report and review of the literature. Changgeng yi xue za zhi. 1992 Jun:15(2):100-4 [PubMed PMID: 1515970]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBuch VP, Madsen PJ, Vaughan KA, Koch PF, Kung DK, Ozturk AK. Rotational vertebrobasilar insufficiency due to compression of a persistent first intersegmental vertebral artery variant: case report. Journal of neurosurgery. Spine. 2017 Feb:26(2):199-202. doi: 10.3171/2016.7.SPINE163. Epub 2016 Oct 7 [PubMed PMID: 27716015]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePaşaoğlu L. Vertebrobasilar system computed tomographic angiography in central vertigo. Medicine. 2017 Mar:96(12):e6297. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000006297. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28328808]

Caplan LR. Atherosclerotic Vertebral Artery Disease in the Neck. Current treatment options in cardiovascular medicine. 2003 Jul:5(3):251-256 [PubMed PMID: 12777203]

Compter A, van der Worp HB, Schonewille WJ, Vos JA, Boiten J, Nederkoorn PJ, Uyttenboogaart M, Lo RT, Algra A, Kappelle LJ, VAST investigators. Stenting versus medical treatment in patients with symptomatic vertebral artery stenosis: a randomised open-label phase 2 trial. The Lancet. Neurology. 2015 Jun:14(6):606-14. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00017-4. Epub 2015 Apr 20 [PubMed PMID: 25908089]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKocak B, Korkmazer B, Islak C, Kocer N, Kizilkilic O. Endovascular treatment of extracranial vertebral artery stenosis. World journal of radiology. 2012 Sep 28:4(9):391-400 [PubMed PMID: 23024840]

Raheja A, Taussky P, Kumpati GS, Couldwell WT. Subclavian-to-Extracranial Vertebral Artery Bypass in a Patient With Vertebrobasilar Insufficiency: 3-Dimensional Operative Video. Operative neurosurgery (Hagerstown, Md.). 2018 Mar 1:14(3):312. doi: 10.1093/ons/opx130. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28973539]

Henry M, Polydorou A, Henry I, Ad Polydorou I, Hugel IM, Anagnostopoulou S. Angioplasty and stenting of extracranial vertebral artery stenosis. International angiology : a journal of the International Union of Angiology. 2005 Dec:24(4):311-24 [PubMed PMID: 16355087]