Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Wrist Extensor Muscles

Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Wrist Extensor Muscles

Introduction

The wrist extensor muscles comprise a significant component of the posterior forearm musculature. These muscles generally originate on or near the lateral epicondyle and insert on the distal forearm or in the hand. Clinical pathology affecting one or multiple muscles in this group is not uncommon. For example, lateral epicondylitis affects 1-5% of the general population.[1][2]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

To achieve neutral wrist extension movements, the extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB), extensor carpi radialis longus (ECRL), and the extensor carpi ulnaris (ECU) muscles act synergistically based on each muscle's insertion and dynamic function. Thus, in various clinical pathologies that may cause a dynamic imbalance between the radial-based extensors (ECRL and ECRB) versus the ulnar-based extensor (ECU), wrist extension will occur with simultaneous and involuntary radial/ulnar deviation.[3]

Thumb extension is carried out by abductor pollicis longus (APL), extensor pollicis brevis (EPB), and extensor pollicis longus (EPL).[3] When referencing the dorsal aspect of the wrist, the EPB and EPL tendons create the medial and lateral borders of the anatomic snuffbox, respectively.

Extension of the second (index finger), third (long finger), fourth (ring finger), and fifth (small finger) digits occurs via the extensor digitorum communis (EDC) muscles. Independent index finger extension can be carried out by the extensor indicis proprius (EIP) muscle. Independent small finger extension is accomplished by the extensor digiti minimi (EDM) muscle.[3]

Extensor tendon zones are a helpful way to identify the region where injuries to the extensor tendons occur in the hand and wrist. Below is a description of the extensor tendon zones:

- Zone I: covers the fingertip to the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint

- Zone II: covers the middle phalanx

- Zone III: located at the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint

- Zone IV: covers the proximal phalanx

- Zone V: situated at the metacarpal phalangeal (MP) joint

- Zone VI: covers the metacarpals

- Zone VII: covers the wrist

- Zone VIII: proximal to the wrist[3]

The thumb zones are classified differently from the tip of the thumb to the carpal-metacarpal joint. Below is a description of the extensor tendon zones of the thumb:

- Zone I: covers the fingertip to the DIP joint

- Zone II: covers the interphalangeal joint

- Zone III: covers the proximal phalanx

- Zone IV: located over the MP joint[3]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The subclavian artery branches off from the aortic arch. As it traverses towards the upper extremity, it becomes the axillary artery at the lateral border of the first rib. It then becomes the brachial artery once it passes the lower edge of the teres minor muscle. Immediately superior to the antecubital fossa, the brachial artery branches into ulnar and radial arteries.[4] The radial artery then continues laterally in the forearm, eventually contributing to the superficial and deep palmar arches in the palmar aspect of the hand. The deep palmar arch derives its main contribution from the deep arterial branch of the radial artery. In contrast, the superficial palmar arch's predominant blood supply is derived from the ulnar artery. The superficial arch also receives contributions from the superficial branch of the radial artery.

The posterior interosseous artery is a branch from the ulnar artery. Once it branches from the ulnar nerve, it travels posterolateral, eventually supplying blood to muscles in the posterior compartment.

Nerves

The radial nerve divides off the posterior cord of the brachial plexus. As it travels to the elbow, it innervates the triceps muscle. A motor nerve that branches from the radial nerve is the posterior interosseous nerve. This nerve branches from the radial nerve at the level of the radiocapitellar joint and are typically located immediately proximal to the supinator muscle in an area of a fibrous band known as the arcade of Frohse.[5][6]

The posterior interosseous nerve (PIN, also known as the dorsal branch of the radial nerve) innervates and then courses between the two heads of the supinator muscle before entering the posterior compartment of the forearm.[7] The PIN innervates the EDC, EDM, and ECU muscles from the superficial wrist extensor compartment. It then innervates the APL, EPB, EPL, and EIP muscles.

The superficial branch of the radial nerve (SBRN) provides sensation to the distal forearm and hand. The SBRN branches from the radial nerve and runs deep to the brachioradialis muscle in the forearm before emerging between the brachioradialis and ECRL muscles approximately 9 cm proximal to the radial styloid. There is variability in the SBRN’s course in the distal forearm.[8]

Muscles

The muscles of the superficial compartment originate on the lateral epicondyle of the humerus. This muscle group is comprised of the brachioradialis muscle, ECRL, ECRB, EDC, EDM, ECU, and anconeus. Below a summary of the general origin and insertion points can be found.

- Brachioradialis origin: proximal lateral epicondyle of the humerus

- Brachioradialis insertion: lateral distal radius

- ECRL origin: proximal lateral epicondyle of the humerus

- ECRL insertion: dorsal surface of the second metacarpal base

- ECRB origin: lateral epicondyle of the humerus

- ECRB insertion: dorsal surface of the second and third metacarpal bases

- EDC origin: lateral epicondyle of the humerus

- EDC insertion: extensor hoods of the pointer, long, ring, and small finger

- EDM origin: lateral epicondyle of the humerus

- EDM insertion: extensor hood of the small finger

- ECU origin: lateral epicondyle of the humerus

- ECU insertion: medial base of the fifth metacarpal

- Anconeus origin: lateral epicondyle of the humerus

- Anconeus insertion: olecranon and proximal posterior ulna

The deep compartment originates in the region of the posterior radius, ulna, or both. The supinator muscle, abductor pollicis longus muscle, extensor pollicis brevis muscle, extensor pollicis longus muscle, and extensor indicis muscle comprise this deep compartment. Below a summary of the general origin and insertion points can be found.

- Supinator origin: superficial lateral epicondyle of the humerus, radial collateral ligament, and annular ligament

- Supinator insertion: the lateral proximal third of the radius

- APL origin: the posterior proximal surface of the ulna and radius

- APL insertion: lateral base of the first metacarpal

- EPB origin: the posterior proximal surface of the radius (distal to abductor pollicis longus)

- EPB insertion: dorsal surface of the base of the thumb

- EPL origin: the posterior proximal surface of the radius (distal to abductor pollicis longus)

- EPL insertion: dorsal surface of the base of the thumb

- EIP origin: posterior surface of the proximal ulna

- EIP insertion: extensor hood of the index finger

The six extensor compartments of the wrist serve as tunnels for tendons to pass from the forearm to the wrist.[9] At the wrist, the extensor retinaculum of the hand overlies the tendons of the extensor compartment of the wrist. It provides support as well as prevents bowstringing of the tendons.[3] The first extensor compartment is comprised of the APL and EPB tendons. The second extensor compartment is comprised of the ECRB and ECRL muscle tendons. The third extensor compartment is comprised of the EPL muscle tendon. The fourth extensor compartment is made up of the EIP and EDC muscle tendons. The fifth extensor compartment contains the EDM muscle tendon. The sixth extensor compartment harbors the ECU muscle tendon.

Physiologic Variants

It is common for physiologic variants to occur in the wrist extensors. Separate synovial sheaths can be present in the first compartment. In this case, the total number of wrist extensor compartments increases from six to seven. There have been reports of fusion of the APL and EPB muscles. A complete absence of the EPB muscle has also been observed.[9] Estimations are that in 30 to 60% of cases, the tendons of the first compartment are partially or wholly separated by a septum. These variations can lead to snapping wrist syndrome.[9]

Reports exist that anatomic variants of the EIP muscle have an incidence of 16%. Variations in the extensor digitorum brevis muscle have a 9% rate of occurrence. In 22% of cadaveric specimens, an aberrant slip of the ECU muscle was observed inserting on the fifth metacarpal.[10]

Three variants of superfluous wrist extensor muscles have previously been described. These variants are the extensor carpi radialis intermedius (ECRI), extensor carpi radialis tertius (ECRT), and extensor carpi radialis accessories (ECRA). Estimates are that ECRA and ECRI are present in 10-20% of individuals. Additionally, the aberrant ERCA muscle is identified as having multiple deviations.[11]

Anatomists have noted several variations in the anatomy of the radial artery. A low origin of the radial artery has an incidence of 0.2% and has multiple variations within itself.[4] A high origin of the radial artery has also been observed, with branch points occurring as high as the axillary artery.[12]

Surgical Considerations

Lateral Epicondylitis

After extensive conservative management has been trialed and has failed to relieve symptoms, surgical intervention is indicated to treat lateral epicondylitis. Surgical intervention aims at debriding angiofibroblastic tissue at the origin of the ECRB. In some instances, tendon repair or complete muscle release may be indicated depending on the extent of pathology appreciated. There are multiple surgical approaches, and there is a lack of evidence supporting one specific surgical technique.[2][13]

Tendon Injury

Extensor tendon injuries occur more frequently than their flexor tendon counterparts. Part of this increased susceptibility to injury is attributed to the natural anatomy, as the extensors are more superficial in location.

Mallet Finger Injuries (Zone I)

Injuries to zone I (i.e., mallet finger injuries) classically result from forced flexion of an extended DIP joint. These injuries present with varying degrees of flexion deformity of the affected finger, with an inability to actively extend the DIP joint. Initial management of most cases utilizes DIP extension splinting and conservative management. In refractory cases, or in cases where a large bony fragment is appreciated on injury radiographs, consider closed reduction percutaneous pinning (CRPP) versus open reduction internal fixation (ORIF). Several techniques are available for the surgical management of mallet finger injuries. One of the more common methods includes the dorsal blocking pin CRPP technique.[14]

Zone II Injuries

If damage occurs to an extensor tendon in zone II, treatment via immobilization and splinting is the management of choice during the acute phase. Tendon repair is indicated in cases where lacerations involve >50% of tendon width. Various tendon repair techniques have been described, and the literature supports utilizing 4-6 strand repair techniques (crossing the laceration site) as these techniques allow patients to begin early active motion postoperatively.

Zone III injuries

An injury to zone III disrupts the central slip over the PIP joint. Finger posturing in a position of PIP flexion and DIP extension or hyperextension characterize central slip injuries. This position is known as the boutonniere deformity. Patients will present with this deformity in part due to the lateral bands of the dorsal interossei muscles.

A physical exam will reveal absent or weak active PIP extension. The most reliable physical examination test for diagnosing a central slip injury is an Elson test:

- The examiner places the injured hand/digit over the edge of a table to allow 90-degree flexion at the PIP joint of interest. Against resistance, the examiner asks the patient to extend the digit. A positive test (i.e., positive central slip injury) includes documentation of weak PIP extension force and compensatory DIP joint rigidity.

- DIP joint rigidity on an exam is indicative of lateral band activation, an involuntary compensatory finding consistent with a central slip injury

- A negative Elson test consists of the DIP joint remaining flexible (or "floppy") during PIP joint extension against resistance.

Conservative management should be attempted before performing surgery. Nonoperative management consists of splinting the PIP joint in full extension for 4 to 6 weeks.

Surgery is indicated in refractory cases, persistent PIP joint instability despite nonoperative splinting, or in the setting of an acute displaced avulsion fracture seen at the base of the middle phalanx. Surgical techniques described include:

- Primary central band repair

- indicated in cases of displaced avulsion fractures or the setting of an open wound requiring irrigation and debridement

- Lateral band relocation techniques

- Terminal tendon tenotomy techniques

- Tendon reconstruction techniques

- PIP joint arthrodesis

- indicated for rheumatoid patients with chronic deformity or in patients with painful, stiff, arthritis PIP joints

Zone IV Injuries

Zone IV is located over the proximal phalanx of the digits (or the thumb metacarpal). These injuries to the digits include injury to the common extensor tendon(s). Repair of the tendon with the aforementioned 4-6 strand techniques also applies to this region. [3]

Zone V Through Zone VIII

Like injuries to zones I-IV, injuries to zones V, VI, VII, and VIII should be managed conservatively when possible. Surgical intervention is indicated for specific injuries to these areas, but the indications and procedures are highly variable and should be individualized to the patient. A caveat includes managing zone V injuries (zone V injuries include disruption over the MCP joint of the digit or the CMC joint of the thumb. Clinicians must rule out "Fight Bite" injuries and carefully inspect the skin for open wounds/lacerations. In this setting, irrigation and debridement should be performed. In closed injuries, clinical suspicion includes ruling out sagittal band ruptures.[3]

Clinical Significance

Lateral Epicondylitis

Lateral epicondylitis (tennis elbow) ranks as one of the most prevalent pathologies affecting the wrist extensor muscles, affecting approximately 1 to 5% of the population.[1][2] This condition is common in individuals who repeatedly extend their wrists, such as tennis players, as they make a backhand shot. This association is why lateral epicondylitis is commonly known as tennis elbow.[2] The ECRB tendon is most commonly affected and will show angiofibroblastic hyperplasia (immature reparative tissue).[2][13]

Affected patients will typically report tenderness to palpation in the region of the lateral epicondyle as well as pain with activities that require wrist extension. This condition is generally diagnosed clinically but may warrant imaging in some cases. Radiographs help to rule out bone disease, arthropathy, and the presence of loose or foreign bodies. Ultrasound is a useful imaging modality that can identify the tendon changes, such as thinning, thickening, or tearing. MRI can provide more information about the nature of the pathology, but this modality is expensive and generally does not correlate accurately with the severity of clinical symptoms.[1] For these reasons, the necessity of imaging is rare in diagnosing this condition.[13]

Treatment in the acute stage of lateral epicondylitis aims to reduce inflammation mainly by rest, ice, and compression of the affected arm. The subacute phase is managed by exercise, stretching, bracing, coordinated rehabilitation, and corticosteroid injection to the affected area.[13] If conservative management fails to relieve symptoms, the patient might benefit from surgical correction.

DeQuervain Tenosynovitis (extensor compartment 1)

DeQuervain tenosynovitis classically affects women more often than men. Amongst women, those who are recently postpartum are commonly affected. Recently there has been a greater occurrence of individuals who frequently send text messages. It is seen as a stenosing synovitis that occurs in the first wrist extensor compartment affecting APL and EPB. Repetitive injury to the APL and EPB tendons impedes the smooth gliding of tendons in the extensor compartment. The flexor retinaculum overlying the compartment becomes thickened, and the tendon sheaths become inflamed.[15]

Pain can be elicited by performing Finkelstein's test. This patient is instructed to adduct their thumb. They then flex all four digits over the thumb and deviate their wrist towards the ulna. A positive test is when this maneuver causes pain. Treatment measures should be conservative. Thumb spica splinting can be used to immobilize the thumb. Corticosteroid injection into the first extensor compartment has a 75 to 80% chance of alleviating symptoms.[15]

Intersection Syndrome (extensor compartment 2)

Distal intersection syndrome is classically experienced by skiers and kickboxers, who present with dorsal wrist pain complaints. This condition is considered rare and can be missed if there is no clinical suspicion of the syndrome.[15] Distal to the extensor retinaculum, the EPL crosses medially over the ECRB and ECRL. Distal intersection syndrome occurs when this area of crossing over becomes inflamed and causes dorsal wrist pain. Conservative treatment is the typical course of management for this condition.[15]

Proximal intersection syndrome is similar to distal intersection syndrome but occurs at the junction where the APL and EPB cross over the ECRB and ECRL. This form of intersection syndrome is more common than distal intersection syndrome. It often affects rowers, weightlifters, individuals performing secretarial work, and carpenters. This condition is typically managed by conservative treatment, including thumb spica splinting, activity modification, non-steroidal anti-inflammatories, and steroid injection in the second extensor compartment.[15]

EPL Tenosynovitis/Drummer's Wrist/EPL Rupture (extensor compartment 3)

EPL tenosynovitis (drummer's wrist) is commonly experienced by patients with rheumatoid arthritis and also in drummers, hence the eponym drummer's wrist. Individuals who experience a distal radius fracture are also at increased risk of this condition.[15] As EPL travels distally in the wrist, it travels medially towards the dorsal surface of the base of the thumb. As it courses medially, it travels distally to Lister's tubercle. Chronic use can create friction between the EPL tendon and Lister's tubercle resulting in inflammation. Treatment is via conservative management, but corticosteroid injection is not indicated in this condition due to increased local tissue pressure.[15]

PIN Compressive Neuropathy

Compression of the PIN can occur in the posterior forearm compartment causing radial tunnel syndrome (RTS). As the PIN enters the posterior compartment of the forearm, it passes deep to the supinator muscle (between its two heads). Compression can occur at five sites, but the Arcade of Frohse is the most common location of the compression. Patients are typically 30 to 50 years old and frequently have a history of prior surgical intervention to the affected arm. RTS is typically unilateral, with the dominant arm more likely affected. Bilateral RTS is rare. Conservative management is typically first-line treatment, including immobilization, non-steroidal anti-inflammatories, activity modifications, and anesthetic injection directly to the compression site. If conservative management fails, then surgical intervention is indicated.[6]

Media

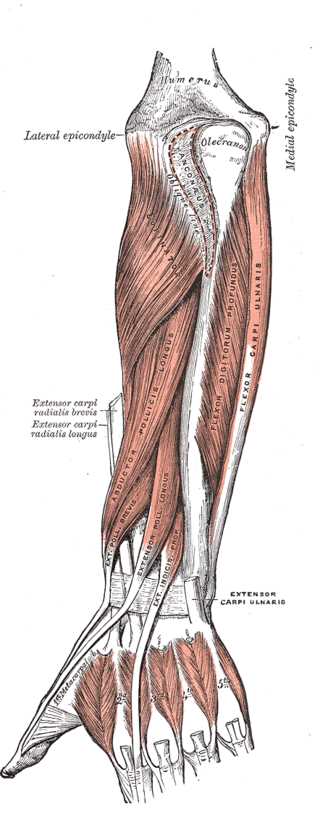

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Muscles of the Forearm, Wrist, and Hand. This posterior view shows the supinator, external carpi radialis longus and brevis, abductor pollicis longus, extensor pollicis brevis and longus, extensor indicis proprius, flexor digitorum profundus, and flexor and extensor carpi ulnaris. Bony structures include the humerus, lateral and medial epicondyles, olecranon, anconeus and oblique line bone markings, and metacarpals 1 to 5.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Vaquero-Picado A, Barco R, Antuña SA. Lateral epicondylitis of the elbow. EFORT open reviews. 2016 Nov:1(11):391-397. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.1.000049. Epub 2017 Mar 13 [PubMed PMID: 28461918]

Nowotny J, El-Zayat B, Goronzy J, Biewener A, Bausenhart F, Greiner S, Kasten P. Prospective randomized controlled trial in the treatment of lateral epicondylitis with a new dynamic wrist orthosis. European journal of medical research. 2018 Sep 15:23(1):43. doi: 10.1186/s40001-018-0342-9. Epub 2018 Sep 15 [PubMed PMID: 30219102]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGriffin M, Hindocha S, Jordan D, Saleh M, Khan W. Management of extensor tendon injuries. The open orthopaedics journal. 2012:6():36-42. doi: 10.2174/1874325001206010036. Epub 2012 Feb 23 [PubMed PMID: 22431949]

Wysiadecki G, Polguj M, Haładaj R, Topol M. Low origin of the radial artery: a case study including a review of literature and proposal of an embryological explanation. Anatomical science international. 2017 Mar:92(2):293-298. doi: 10.1007/s12565-016-0371-9. Epub 2016 Sep 15 [PubMed PMID: 27631096]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOng C, Nallamshetty HS, Nazarian LN, Rekant MS, Mandel S. Sonographic Diagnosis Of Posterior Interosseous Nerve Entrapment Syndrome. Radiology case reports. 2007:2(1):1-4. doi: 10.2484/rcr.v2i1.67. Epub 2016 Jan 5 [PubMed PMID: 27303450]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMoradi A, Ebrahimzadeh MH, Jupiter JB. Radial Tunnel Syndrome, Diagnostic and Treatment Dilemma. The archives of bone and joint surgery. 2015 Jul:3(3):156-62 [PubMed PMID: 26213698]

Vergara-Amador E, Ramírez A. Anatomic study of the extensor carpi radialis brevis in its relation with the motor branch of the radial nerve. Orthopaedics & traumatology, surgery & research : OTSR. 2015 Dec:101(8):909-12. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2015.09.030. Epub 2015 Nov 5 [PubMed PMID: 26547256]

Folberg CR, Ulson H Jr, Scheidt RB. THE SUPERFICIAL BRANCH OF THE RADIAL NERVE: A MORPHOLOGIC STUDY. Revista brasileira de ortopedia. 2009 Jan:44(1):69-74. doi: 10.1016/S2255-4971(15)30052-5. Epub 2015 Dec 6 [PubMed PMID: 26998456]

Subramaniyam SD, Purushothaman R, Zacharia B. Snapping wrist due to multiple accessory tendon of first extensor compartment. International journal of surgery case reports. 2018:42():182-186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2017.12.004. Epub 2017 Dec 13 [PubMed PMID: 29253811]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHinds RM, Gottschalk MB, Melamed E, Capo JT, Yang SS. Accessory Slip of the Extensor Carpi Ulnaris: A Cadaveric Assessment. Journal of wrist surgery. 2016 Nov:5(4):273-276 [PubMed PMID: 27777817]

West CT, Ricketts D, Brassett C. An anatomical study of additional radial wrist extensors including a unique extensor carpi radialis accessorius. Folia morphologica. 2017:76(4):742-747. doi: 10.5603/FM.a2017.0047. Epub 2017 May 29 [PubMed PMID: 28553852]

Haładaj R, Wysiadecki G, Dudkiewicz Z, Polguj M, Topol M. The High Origin of the Radial Artery (Brachioradial Artery): Its Anatomical Variations, Clinical Significance, and Contribution to the Blood Supply of the Hand. BioMed research international. 2018:2018():1520929. doi: 10.1155/2018/1520929. Epub 2018 Jun 11 [PubMed PMID: 29992133]

Inagaki K. Current concepts of elbow-joint disorders and their treatment. Journal of orthopaedic science : official journal of the Japanese Orthopaedic Association. 2013 Jan:18(1):1-7. doi: 10.1007/s00776-012-0333-6. Epub 2013 Jan 11 [PubMed PMID: 23306537]

Akgun U, Bulut T, Zengin EC, Tahta M, Sener M. Extension block technique for mallet fractures: a comparison of one and two dorsal pins. The Journal of hand surgery, European volume. 2016 Sep:41(7):701-6. doi: 10.1177/1753193416647725. Epub 2016 May 10 [PubMed PMID: 27165982]

Meraj S, Gyftopoulos S, Nellans K, Walz D, Brown MS. MRI of the Extensor Tendons of the Wrist. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2017 Nov:209(5):1093-1102. doi: 10.2214/AJR.17.17791. Epub 2017 Aug 31 [PubMed PMID: 28858545]