Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Posterior Abdominal Wall Arteries

Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Posterior Abdominal Wall Arteries

Introduction

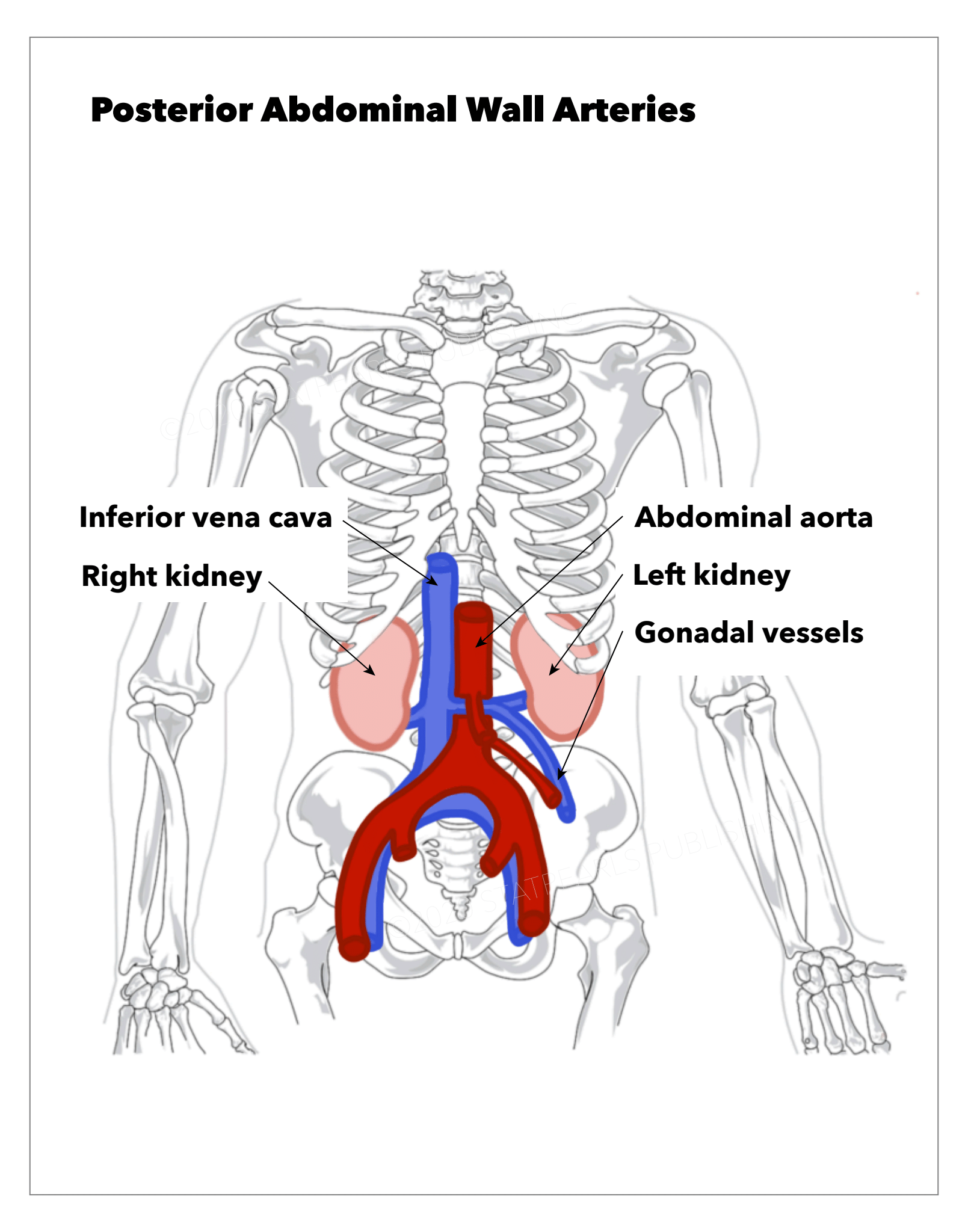

Several arteries course through the posterior abdominal wall (see Image. Posterior Abdominal Wall Arteries).

- The aorta passes the aortic hiatus at the T12 level through the diaphragm and descends anterior to the vertebral column. The aorta branches into the right and left common iliac arteries at L4. The aorta gives rise to the inferior phrenic arteries below the aortic hiatus. These vessels supply the diaphragm and also give rise to the suprarenal vessels.

- The renal arteries arise from the aorta just inferior to the origin of the superior mesenteric artery. The right renal artery is longer and a little inferior to the left renal artery and traverses behind the inferior vena cava (IVC). The left renal artery passes posterior to the left renal vein.

- Testicular or ovarian arteries descend into the retroperitoneum and run laterally on the psoas major muscle and across the ureter. The testicular artery accompanies the ductus deferens into the scrotum. Here, it provides blood to the epididymis, testis, and spermatic cord. The ovarian artery traverses through the suspensory ligament of the ovary supplies the ovary, and anastomosis with the ovarian branch of the uterine artery.

- Lumbar arteries consist of 4 or 5 pairs that originate from the back of the aorta. These vessels require ligation when performing aortic aneurysm surgery. They run posterior to the sympathetic trunk, the IVC (on the right side), the quadratus lumborum, and the psoas major muscles. The lumbar vessels give off numerous small anterior branches that accompany the dorsal primary rami of the corresponding spinal nerves and divide into spinal and muscular branches.

- The middle sacral artery comes off the posterior of the aorta, just above the bifurcation; the vessel then runs down the anterior of the sacrum and ends at the coccygeal body. It supplies the anal canal and rectum and joins the superior and inferior rectal arteries.

In the posterior abdominal wall, other important vessels that are not arteries include:

- IVC is formed by the union of the two common iliac veins just to the right of L5. The bifurcation of the IVC is almost always lower than the bifurcation of the aorta in the pelvis. As it ascends, the IVC remains to the right of the aorta. At the diaphragm, it ascends through the IVC hiatus at T8 and enters the right atrium. Through its course, it receives venous blood from the adrenals, renal veins, right gonads, hepatic veins, and inferior phrenic veins.

- The cisterna chyli, formed by the lumbar and intestinal lymphatics, lies just posterior and to the right of the aorta. It is usually located between the two crura of the diaphragm and ascends through the aortic hiatus in the diaphragm. The cisterna chyli is the inferior collecting sac of the thoracic duct, which returns the chyle to the venous system at the left brachiocephalic vein, where the left subclavian and left internal jugular veins converge.

- The para-aortic lymph nodes can divide into subgroups, including the preaortic, retroaortic, and lateral aortic groups. The preaortic nodes are located next to the origin of the celiac trunk and superior and inferior mesenteric arteries.

Surgeons, radiologists, and other health professionals need to be familiar with these vessels as multiple pathologic conditions may develop, resulting in untoward consequences from vessel injury (see Image. Bolus Tracking).

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The branches of the abdominal aorta are as follows, along with their function:

- Inferior phrenic arteries are paired arteries that supply the diaphragm and branch to become the superior suprarenal artery to help supply the adrenal glands.

- The celiac trunk has three main branches:

- The left gastric artery supplies the lesser curvature of the stomach.

- The common hepatic artery branches into the hepatic artery to supply the gallbladder via the cystic artery and the right and left hepatic arteries to supply the liver. The common hepatic artery also branches into the gastroduodenal artery, which branches into the right gastroepiploic/right gastro-omental artery and superior pancreaticoduodenal artery. These branches supply the greater curvature and pancreas and duodenum, respectively.

- The splenic artery runs superior to the pancreas. In addition to supplying the spleen, it provides branches to the pancreas. This short gastric artery supplies the fundus and greater curvature of the stomach; the left gastroepiploic/gastro-omental artery supplies the greater curvature of the stomach, and the posterior gastric artery, which, as the name denotes, supplies the posterior aspect of the stomach.

- Middle suprarenal arteries are bilateral arteries that contribute to the supply of the adrenal glands.

- Lumbar arteries: There are usually four paired lumbar arteries, and they supply the Quadratus lumborum muscles bilaterally.

- The superior mesenteric artery supplies the small bowel (duodenum, jejunum, ileum) up to the proximal two-thirds of the transverse colon and supplies the pancreas.

- Renal arteries are bilateral structures that supply the kidneys.

- Testicular/ovarian arteries supply the gonads.

- The inferior mesenteric artery supplies the distal one-third of the transverse colon to the upper aspect of the rectum.

- The median sacral artery branches from the abdominal aorta before it bifurcates and supplies the sacrum and lumbar vertebrae.

The abdominal aorta bifurcates at L4 to become the right and left common iliac arteries, which eventually become the internal (hypogastric artery) and external iliac arteries that supply the pelvis and lower extremities, respectively.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

- Preaortic lymph nodes drain lymphatics from the spleen, gastrointestinal (GI) tract, gallbladder, pancreas, and liver.

- The para-aortic drains lymphatics from the suprarenal glands, kidneys, testis, uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries.[1]

Physiologic Variants

The lumbar arteries are typically 4 paired vessels. However, a fifth pair may exist as branches of the median sacral artery.

Surgical Considerations

Pringle maneuver, or the clamping the hepatoduodenal ligament, which contains the hepatic artery proper, the portal vein, and the common bile duct, can help determine the source of intraabdominal bleeding either in a trauma emergency setting or a more controlled elective hepatic surgical procedure. If intraabdominal bleeding continues after clamping the hepatoduodenal ligament in a trauma setting, it is necessary to interrogate the inferior vena cava and hepatic vein as potential sources of bleeding. The Pringle maneuver can also be used during elective surgeries to control blood loss when the liver is a target of surgical intervention.

Clinical Significance

Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm

Major risk factors for developing AAA include cigarette smoking and hypertension. Additionally, individuals with Marfan or Ehlers-Danlos syndrome are at risk of developing AAAs. Men are at greater risk. The majority of AAAs develop below the renal artery branches of the abdominal aorta. Routine screening using abdominal ultrasound for AAAs (in the United States) is done for men over the age of 65 who have a history of smoking or who are current smokers. If the abdominal aorta has a diameter greater than 3 cm, this is considered AAA. However, surgical intervention is reserved for AAAs that grow to greater than 5.5 centimeters or if the AAA grows greater than 1 centimeter within 1 year while doing ultrasound surveillance of a known AAA. Surgical intervention can be open repair or with the use of endovascular repair.[2][3][4]

Nutcracker Syndrome

The left renal vein runs between the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and the abdominal artery on its way to drain into the inferior vena cava (IVC), and the left renal vein can be compressed between the SMA and abdominal aorta, potentially leading to hematuria and left-sided flank pain. The right renal vein does not cross the aorta to drain into the IVC and is, therefore, not susceptible to compression between the SMA and abdominal aorta.[5][6]

Splenic Artery Aneurysm

If there is an aneurysm of the splenic artery, there is potential for upper GI bleeding as the short gastric artery will have a build-up of back pressure.[7]

Other Issues

Although rare, using Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) intravesical therapy for bladder cancer has disseminated and led to mycotic aneurysms of posterior wall vessels, including the common iliac arteries and abdominal aorta.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Bolus Tracking. This is an example of bolus tracking in the use of imaging an abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA), radiopaque, CT Scan, computer tomography scan.

Glitzy queen00, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Le O. Patterns of peritoneal spread of tumor in the abdomen and pelvis. World journal of radiology. 2013 Mar 28:5(3):106-12. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v5.i3.106. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23671747]

Selçuk İ, Yassa M, Tatar İ, Huri E. Anatomic structure of the internal iliac artery and its educative dissection for peripartum and pelvic hemorrhage. Turkish journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2018 Jun:15(2):126-129. doi: 10.4274/tjod.23245. Epub 2018 Jun 21 [PubMed PMID: 29971190]

Megalopoulos A, Ioannidis O, Varnalidis I, Ntoumpara M, Tsigriki L, Alexandris K, Anastasiadou C, Styliani P, Paraskevas G, Mantzoros I. High prevalence of abdominal aortic aneurysm in patients with inguinal hernia. Biomedical papers of the Medical Faculty of the University Palacky, Olomouc, Czechoslovakia. 2019 Sep:163(3):247-252. doi: 10.5507/bp.2018.077. Epub 2019 Jan 30 [PubMed PMID: 30697034]

Hollingsworth AC,Dawkins C,Wong PF,Walker P,Milburn S,Mofidi R, Aneurysm Morphology is a More Significant Predictor of Survival than Hardman's Index in Patients with Ruptured or Acutely Symptomatic Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms. Annals of vascular surgery. 2019 Jan 23; [PubMed PMID: 30684631]

Oz M, Hazirolan T, Turkbey B, Karaosmanoglu AD, Canyigit M, Peynircioglu B. CT angiography evaluation of the renal vascular pathologies: a pictorial review. JBR-BTR : organe de la Societe royale belge de radiologie (SRBR) = orgaan van de Koninklijke Belgische Vereniging voor Radiologie (KBVR). 2010 Sep-Oct:93(5):252-7 [PubMed PMID: 21179985]

Tong ZY, Zheng ZL, Wang JL, Mou Y, Yao L, Zhao JK, Xu QB. [Ultrasonic evaluation of nut cracker syndrome before and after stent implantation]. Zhejiang da xue xue bao. Yi xue ban = Journal of Zhejiang University. Medical sciences. 2005 Sep:34(5):473-5 [PubMed PMID: 16216063]

De Silva WSL, Gamlaksha DS, Jayasekara DP, Rajamanthri SD. A splenic artery aneurysm presenting with multiple episodes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a case report. Journal of medical case reports. 2017 May 3:11(1):123. doi: 10.1186/s13256-017-1282-7. Epub 2017 May 3 [PubMed PMID: 28468689]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence