Introduction

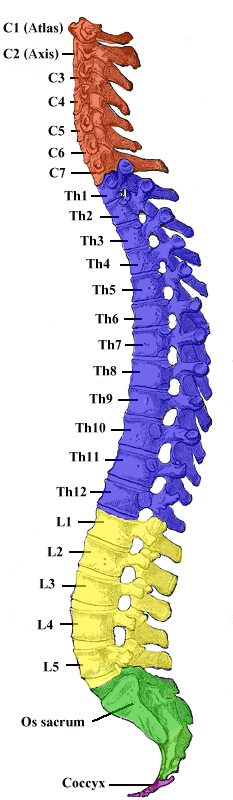

Vertebrae, along with intervertebral discs, compose the vertebral column or spine. It extends from the skull to the coccyx and includes the cervical, thoracic, lumbar, and sacral regions. The spine has several major roles in the body that include: protection of the spinal cord and branching spinal nerves, support for thorax and abdomen, and enables flexibility and mobility of the body. The intervertebral discs are responsible for this mobility without sacrificing the supportive strength of the vertebral column. The thoracic region contains 12 vertebrae, denoted T1-T12. The intervertebral discs, along with the laminae, pedicles, and articular processes of adjacent vertebrae, create a space through which spinal nerves exit. The thoracic vertebrae, as a group, produce a kyphotic curve. Thoracic vertebrae are unique in that they have the additional role of providing attachments for the ribs.[1][2][3]

Typical vertebrae consist of a vertebral body, a vertebral arch, as well as seven processes. The body bears the majority of the force placed on the vertebrae. Vertebral bodies increase in size from superior to inferior. The vertebral body consists of a trabecular bone, which contains the red marrow, surrounded by a thin external layer of compact bone. The arch, along with the posterior aspect of the body, forms the vertebral (spinal) canal, which contains the spinal cord. The arch consists of bilateral pedicles, cylindrical segments of bone that connect the arch to the body, and bilateral lamina, bone segments form most of the arch, connecting the transverse and spinous processes. A typical vertebra also contains four articular processes, two superior and two inferior, which contact the inferior and superior articular processes of adjacent vertebrae, respectively. The point at which superior and articular facets meet is known as a facet, or zygapophyseal, joint. These maintain vertebral alignment, control the range of motion, and are weight-bearing in certain positions. The spinous process projects posteriorly and inferiorly from the vertebral arch and overlaps the inferior vertebrae to various degrees, depending on the region of the spine. Lastly, two transverse processes project laterally from the vertebral arch in a symmetric fashion.

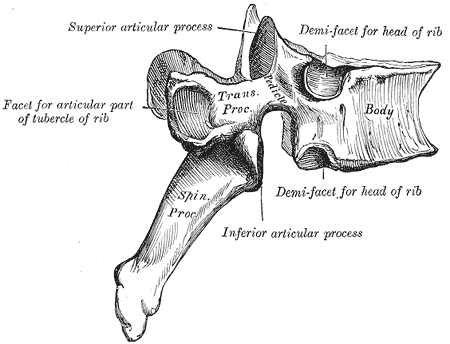

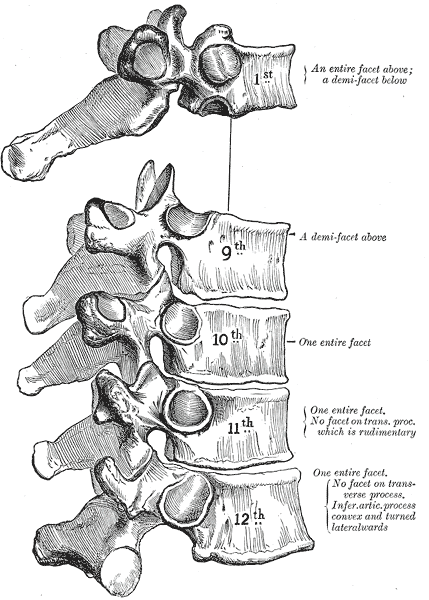

Typical thoracic vertebrae have several features distinct from those typical of cervical or lumbar vertebrae. T5-T8 tend to be the most “typical” because they contain features present in all thoracic vertebrae. The primary characteristic of the thoracic vertebrae is the presence of costal facets. There are six facets per thoracic vertebrae: two on the transverse processes and four demifacets—the facets of the transverse processes articulate with the tubercle of the associated rib. The demifacets are bilaterally paired and located on the superior and inferior posterolateral aspects of the vertebrae. They are positioned so that the superior demifacet of the inferior vertebrae articulates with the head of the same rib that articulates with the inferior demifacet of the superior rib. For example, the inferior demifacets of T4 and the superior demifacets of T5 articulate with the head of rib 5. The length of the transverse processes decreases as the column descends. The positioning of the ribs and spinous processes greatly limits flexion and extension of the thoracic vertebrae. However, T5-T8 have the greatest rotation ability of the thoracic region. Thoracic vertebrae have superior articular facets that face in a posterolateral direction. The spinous process is long, relative to other regions, and is directed posteroinferiorly. This projection gradually increases as the column descends before decreasing rapidly from T9-T12. The intervertebral disc height is, on average, the least of the vertebral regions.

There are three atypical vertebrae found in the thoracic region:

The superior costal facets of T1 are “whole” costal facets. They alone articulate with the first rib; C7 has no costal facets. T1 does, however, have typical inferior demifacets for articulation with the second rib. T1 also has a long, almost horizontal spinous process, similar to a cervical vertebra that may be as long as the vertebra prominens of C7.

T11 and T12 are atypical in that they contain a single pair, “whole,” costal facet that articulate with the 11 and 12 ribs, respectively. They also lack facets on the transverse processes. It varies by individual, but T10 may resemble the atypical nature of the 11 and 12 vertebrae. When that is the case, T9 lacks an inferior demifacet, as it would not be needed to articulate with the 10th rib.

Additionally, T12 is unique in that it represents a transition from the thoracic to the lumbar vertebra. It is thoracic in that it contains costal facets and superior articular facets that allow for rotation, flexion, and rotation. It is lumbar in that it has articular processes that do not allow for rotation, only flexion, and extension. It also contains mammillary processes, small tubercles located on the posterior surface of the superior articular processes, which allow for attachment for the intertransversarii and multifidus muscles.[4]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

As with all physiology, the anatomy of a structure is related directly to its function. The facets and demifacets devoted to rib articulation demonstrate the main function of the thoracic spine. The zygapophyseal joints are tight enough to protect vital organs but loose enough to allow for respiratory movements and allow the thoracic segment to have the greatest freedom of rotation of the entire spine. The zygapophyseal joints, as well as the relatively thin intervertebral discs, cause the thoracic region to have the least flexion/extension ability of the spine. Also, the noted increase in vertebral body size as the spinal column descends is directly related to the increased weight-bearing requirement; further down the column, the greater the proportion of body mass that rests upon it.[5]

Embryology

All vertebrae begin ossification in the embryonic period of development around 8 weeks of gestation. They ossify from three primary ossification centers: one in the endochondral centrum (which will develop into the vertebral body) and one in each neural process (which will develop into the pedicles). This begins at the thoracolumbar junction and proceeds in the cranial and caudal directions. The neural processes fuse with the centrum in between three and six years of age. During puberty, five secondary ossification centers develop at the tip of the spinous process and both transverse processes and on the superior and inferior surfaces of the vertebral body. The ossification centers on the vertebral body are responsible for the superior-inferior growth of the vertebrae. Ossification completes around the age of 25.[6]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The thoracic vertebrae are mainly supplied by branches of the posterior intercostal arteries. The first two posterior intercostal arteries branch off the subclavian artery, while the remaining branch off the thoracic aorta. These main arteries branch out into the periosteal and equatorial arteries, which subsequently branch into anterior and posterior canal branches. Anterior vertebral canal branches send nutrient arteries into the vertebral body to supply the red marrow.

Spinal veins form venous plexuses inside and outside the vertebral canal. These plexuses are valve-less and allow for the movement of blood superiorly or inferiorly depending on pressure gradients. The blood eventually drains into the segmental veins of the trunk.

Nerves

Meningeal branches of spinal nerves innervate all vertebrae.

Muscles

Thoracic vertebrae provide attachment points for numerous muscles: erector spinae, interspinales, intertransversarii, latissimus dorsi, multifidus, rhomboid major, rhomboid minor, rotatores, semispinalis, serratus posterior superior/inferior, splenius capitis, splenius cervicis, and trapezius.

Surgical Considerations

Thoracic spine surgeries provide unique challenges to the surgeons due to:

- The narrow canal diameter

- The close relation to important vascular structures including the aorta (covers T3-T7 on the left side), sympathetic chain (T1-T12), and azygos vein (crosses lateral spinal column at T4-T5)

- Narrow pedicles

Clinical Significance

Approximately 90% of all spinal injuries involve the thoracolumbar region (T10-L2), 50% of which can be unstable and lead to a neurological deficit.[7][8]

The thoracic spine has a relatively narrow vertebral canal, which predisposes it to spinal cord damage and neurological deficit. However, the thoracic spine is functionally rigid due to the orientation of the facet joints, the thin intervertebral discs, and the ribcage. Therefore, it requires a greater amount of energy (force of trauma) to produce fractures and dislocations.

As T12 has characteristics of both thoracic and lumbar vertebrae, it is subject to transitional stresses. These transitional forces result from the change from the rigid thoracic spine to the relatively mobile lumbar spine. This causes it to be the most commonly fractured vertebra.

The valve-less vertebral venous plexuses allow the metastasis of cancer from the pelvis, such as that of the prostatic, to the vertebral column.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

DeSai C, Reddy V, Agarwal A. Anatomy, Back, Vertebral Column. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30247844]

Mrozkowiak M, Walicka-Cupryś K, Magoń G. Comparison of Spinal Curvatures in the Sagittal Plane, as Well as Body Height and Mass in Polish Children and Adolescents Examined in the Late 1950s and in the Early 2000s. Medical science monitor : international medical journal of experimental and clinical research. 2018 Jun 30:24():4489-4500. doi: 10.12659/MSM.907134. Epub 2018 Jun 30 [PubMed PMID: 29959309]

Movahed A, Majdalany D, Gillinov M, Schiavone W. Association Between Myxomatous Mitral Valve Disease and Skeletal Back Abnormalities. The Journal of heart valve disease. 2017 Sep:26(5):564-568 [PubMed PMID: 29762925]

Waxenbaum JA, Reddy V, Futterman B. Anatomy, Back, Intervertebral Discs. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29262063]

Bogduk N. Functional anatomy of the spine. Handbook of clinical neurology. 2016:136():675-88. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-53486-6.00032-6. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27430435]

Kalamchi L, Valle C. Embryology, Vertebral Column Development. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31751107]

Waxenbaum JA, Reddy V, Black AC, Futterman B. Anatomy, Back, Cervical Vertebrae. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29083805]

Shanbhag NC, Duyff RF, Groen RJM. Symptomatic Thoracic Nerve Root Herniation into an Extradural Arachnoid Cyst: Case Report and Review of the Literature. World neurosurgery. 2017 Oct:106():1056.e5-1056.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.07.105. Epub 2017 Jul 25 [PubMed PMID: 28754642]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence