Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Hip Joint

Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Hip Joint

Introduction

The hip joint is a ball and socket joint that is the point of articulation between the head of the femur and the acetabulum of the pelvis. The joint is a diarthrodial joint with its inherent stability dictated primarily by its osseous components/articulations. The primary function of the hip joint is to provide dynamic support to the weight of the body/trunk while facilitating force and load transmission from the axial skeleton to the lower extremities, allowing mobility.[1][2][3]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The hip joint connects the lower extremities with the axial skeleton. The hip joint allows for movement in three major axes, all of which are perpendicular to one another. The location of the center of the entire axis is at the femoral head. The transverse axis permits flexion and extension movement. The longitudinal axis, or vertically along the thigh, allows for internal and external rotation. The sagittal axis, or forward to backward, allows for abduction and adduction.[4][5]

In addition to movement, the hip joint facilitates weight-bearing. Hip stability arises from several factors. The shape of the acetabulum. Due to the depth of the acetabulum, it can encompass almost the entire head of the femur. There is an additional fibrocartilaginous collar surrounding the acetabulum, the acetabular labrum, which provides the following functions:

- Load transmission

- Negative pressure maintenance (i.e., the "vacuum seal") to enhance hip joint stability

- Regulation of synovial fluid hydrodynamic properties

The hip joint capsule and capsular ligaments

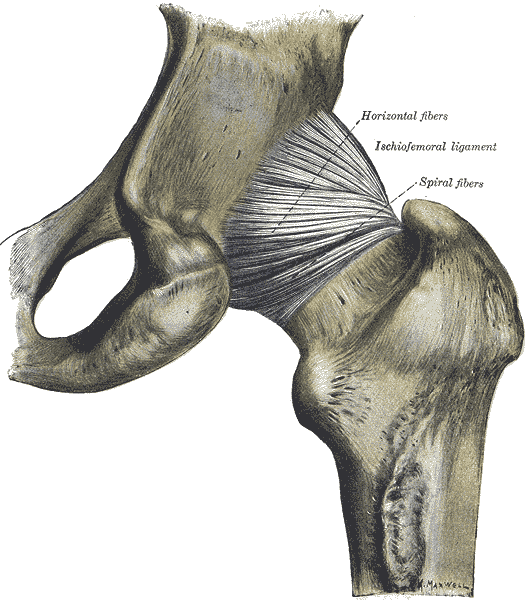

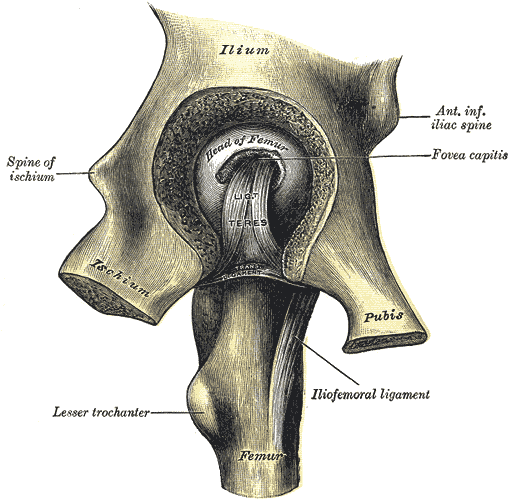

In general, the hip joint capsule is tight in extension and more relaxed in flexion. The capsular ligaments include the iliofemoral ligament (Y ligament of Bigelow), and the pubofemoral and ischiofemoral ligaments. The iliofemoral ligament is the strongest ligament in the body and attaches the anterior inferior iliac spine (AIIS) to the intertrochanteric crest of the femur. The pubofemoral ligament prevents excess abduction and extension, ischiofemoral prevents excess extension, and the iliofemoral prevents hyperextension.

The ligamentum teres (ligament of the head of the femur) are located intracapsular and attach the apex of the cotyloid notch to the fovea of the femoral head. The ligamentum teres serves as a carrier for the foveal artery (a posterior division of the obturator artery), which supplies the femoral head in the infant/pediatric population. This relative vascular contribution to the femoral head blood supply is negligible in adults. Injuries to the ligamentum teres can occur in dislocations, which can cause lesions of the foveal artery, resulting in osteonecrosis of the femoral head.

Embryology

By gestational age weeks 4 to 6, the hip joint begins to develop from mesoderm. By seven weeks gestational age, a cleft forms in the precartilage cells, which are programmed to form the femoral head and acetabulum. By 11 weeks of gestational age, the hip joint has mostly formed. The acetabular cartilage completely encircles the femoral head.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

There are numerous variations in the blood supply to the hip. The most common variant results in blood supply coming from the medial circumflex and lateral circumflex femoral arteries, each of which is a branch of the profunda femoris (deep artery of the thigh). The profunda femoris is a branch of the femoral artery which travels posteriorly. There is an additional contribution from the foveal artery (artery to the head of the femur), a branch of the posterior division of the obturator artery, which travels in the ligament of the head of the femur. The foveal artery helps avoid avascular necrosis with disruption of the medial and lateral circumflex arteries. There are two significant anastomoses. The cruciate anastomosis supports the upper thigh and the trochanteric anastomosis, which supports the head of the femur.

Lymphatic drainage from the anterior aspect drains to the deep inguinal nodes, while the medial and posterior aspects drain into the internal iliac nodes.

Nerves

The hip joint receives innervations from the femoral, obturator, superior gluteal nerves.[6]

Muscles

Muscles of the hip joint can be grouped based upon their functions relative to the movements of the hip.[1]

- Flexion: Primarily accomplished via the psoas major and the iliacus, with some assistance from the pectineus, rectus femoris, and the sartorius.

- Extension: Primarily accomplished via the gluteus maximus as well as the hamstring muscles.

- Medial rotation: Primarily accomplished by the tensor fascia latae and fibers of the gluteus medius and minimus.

- Lateral rotation: Primarily accomplished by the obturator muscles, the quadratus femoris, and the gemelli with assistance from the gluteus maximus, sartorius, and piriformis.

- Adduction: Primarily accomplished by the adductor longus, brevis, and magnus with assistance from the gracilis and pectineus

- Abduction: Primarily accomplished by the gluteus medius and minimus with assistance from the tensor fascia latae and sartorius.

Surgical Considerations

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is an elective procedure for patients with hip pain secondary to degenerative conditions. THA is a highly effective procedure that relieves pain and restores function to improve quality of life. THA is indicated for patients who have failed other conservative methods, including corticosteroid injections, physical therapy, weight reduction, or previous surgical treatments.[7][8]

Approaches

Surgeons can utilize any number of strategies for the THA procedure. The three most common approaches are as follows:

Posterolateral

This is the most common approach for primary and revision THA cases. This dissection does not utilize a true internervous plane. The intermuscular interval involves blunt dissection of the gluteus maximus fibers and sharp incision of the fascia lata distally. The deep dissection involves a meticulous dissection of the short external rotators and capsule. Care is necessary to protect these structures as they are later repaired back to the proximal femur via trans-osseous tunnels.

A significant advantage of this approach is the avoidance of hip abductors. Other benefits include the excellent exposure provided for both the acetabulum and the femur and the optional extensile conversion in the proximal or distal direction. Historically, some studies comparing this approach to the direct anterior (DA) approach have cited higher dislocation rates in the former approach. This data remains inconclusive and controversial as the literature has not established a definitive consensus, especially when comparing the posterior approach technique that utilizes an optimal soft tissue repair at the conclusion of the THA procedure.

Direct Anterior (DA)

The DA approach is becoming increasingly popular among THA surgeons. The internervous interval is between the tensor fascia lata (TFL) and sartorius on the superficial end, and the gluteus medius and rectus femoris (RF) on the deep side. DA THA advocates cite the theoretical decreased hip dislocation rates in the postoperative period and the avoidance of the hip abduction musculature.

The disadvantages include the learning curve associated with the approach, as the literature documents the decreased complication rates after a surgeon surpasses the more than 100-case mark. Other disadvantages include increased wound complications, difficult femoral exposure, the risk of lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (LFCN) paresthesias, and a potentially higher rate of intra-operative femur fractures. Finally, many surgeons need access to a specialized operating table with appropriately trained personnel and surgical technicians to assist in the procedure. Although the latter is not always necessary, learning to do the procedure on a regular operating table also requires a substantial learning curve that one must consider.

Anterolateral

Compared to the other approaches, the anterolateral (AL) approach is the least commonly used approach secondary to its violation of the hip abductor mechanism. The interval exploited includes that of the TFL and gluteus medius musculature; this may lead to a postoperative limp as the tradeoff of a theoretically decreased dislocation rate.

Clinical Significance

Congenital Hip Dislocation/Dysplasia

Also known as developmental dysplasia of the hip, this can arise when there are problems with the development of the hip joint in utero. Risk factors include breech presentation, positive family history, and oligohydramnios. Diagnosis is possible via physical exam with the Barlow and Ortolani maneuvers, which assess joint stability. Additional characteristic findings are leg length asymmetry as well as asymmetric inguinal skin folds.

The ultimate goal of treatment is the open or closed reduction of the femoral head back into the acetabulum. The earlier treatment starts, the better the outcomes. Mild cases can correct spontaneously by two weeks. When subluxation persists for more than two weeks, it indicates the need for treatment. Standard treatment is the use of the Pavlik Harness, which positions the hips into flexion and abduction for six weeks full-time, followed by six weeks part-time.[9]

Traumatic Conditions

Commonly seen in the setting of trauma, posterior dislocation occurs in the setting of high-energy trauma or motor vehicle accidents (MVAs). The femoral head is transmitted posteriorly, injuring the hip joint capsule. The affected lower extremity presents in a shortened, internally rotated position. In all traumatic injuries, there is extensive soft tissue injury about the hip joint and capsule, and in the vast majority of presentations, there will be an associated posterior wall (acetabular) fracture and/or femoral head fracture. The positioning of the hip often determines the associated acetabular injury.

Patients will typically present with significant pain and inability to bear weight. Approximately 10% of cases may have concurrent damage to the sciatic nerve. Treatment consists of both nonoperative and operative measures. In the acute setting, emergent closed reduction is recommended within six hours of the injury. Following a successful closed reduction, a CT scan can assess and evaluate the extent of associated osseous injuries. Additionally, the presence of incarcerated fragments in the joint is of utmost importance as appreciably large fragments will not only prevent the complete reduction of the native hip joint but these fragments also potentially can cause further intra-articular damage and chondral injuries secondary to mechanical abrasion and pathologic contact/abutment.

Irreducible dislocations, those with evidence of incarcerated fragments, and delayed presentations are treated via operative open reduction urgently. Open reduction with internal fixation is the recommendation for complex dislocations with evidence of acetabular or femoral fractures.

Osteoarthritis of the Hip

Most commonly presents in adults, greater than 40 years old. Symptoms include pain, disability, ambulatory dysfunction, and stiffness/contracture. The patient typically feels pain in the anterior groin, and occasionally involving the buttocks and lateral thigh. Some patients can develop generalized hip referred pain of the knee. It is crucial to consider and/or rule out co-existing lumbar spinous pathology/radiculopathy, and ipsilateral knee conditions.

The pathogenesis involves wear and tear on the joint cartilage, which over time, leads to decreased protective joint space. As bones begin to rub on one another, they attempt to make up for the lost cartilage and form bone spurs or osteophytes. Nonsurgical treatments involve lifestyle modifications such as weight loss, or minimizing activates that exacerbate pain. Physical therapies, the use of assistive devices, and medications such as NSAIDs, acetaminophen, and corticosteroids also show evidence of effectiveness. For patients whose pain is still irretraceable, surgical intervention may need to be required. Surgical options include osteotomy, hip resurfacing, and total hip replacement.[10]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Ramage JL, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Medial Thigh Muscles. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30521196]

Chang A, Breeland G, Hubbard JB. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Femur. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30422577]

Chang C, Jeno SH, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Piriformis Muscle. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30137781]

Bordoni B, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Thigh Quadriceps Muscle. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30020706]

Glenister R, Sharma S. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Hip. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30252275]

Perumal V, Woodley SJ, Nicholson HD. Neurovascular structures of the ligament of the head of femur. Journal of anatomy. 2019 Jun:234(6):778-786. doi: 10.1111/joa.12979. Epub 2019 Mar 18 [PubMed PMID: 30882902]

Arias-de la Torre J, Puigdomenech E, Valderas JM, Evans JP, Martín V, Molina AJ, Rodríguez N, Espallargues M. Availability of specific tools to assess patient reported outcomes in hip arthroplasty in Spain. Identifying the best candidates to incorporate in an arthroplasty register. A systematic review and standardized assessment. PloS one. 2019:14(4):e0214746. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0214746. Epub 2019 Apr 1 [PubMed PMID: 30934024]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceVaracallo M, Bordoni B. Hip Pointer Injuries. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30855846]

Deak N, Varacallo M. Hip Precautions. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30725716]

Stirton JB, Maier JC, Nandi S. Total hip arthroplasty for the management of hip fracture: A review of the literature. Journal of orthopaedics. 2019 Mar-Apr:16(2):141-144. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2019.02.012. Epub 2019 Feb 26 [PubMed PMID: 30886461]