Introduction

As social and highly developed mammals, humans communicate through numerous means to convey information such as speech, written word or symbols, touch, and gesture. A key gesture for visual and spoken communication is through facial expression. Since birth, a human begins to convey thoughts and feelings by any range of universal facial expressions (e.g., smiles and frowns). These expressions are expressed worldwide, across all races and overcome language barriers. As such, the organs through which humans communicate visual expression are a finely coordinated neuromuscular complex. The platysma is often an overlooked muscle of facial expression due to its location on the neck, but it contributes nonetheless.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The platysma is a superficial muscle found in the neck. It covers most of the anterior and lateral aspect of the neck. The platysma is a broad muscle which arises from the fascia that covers the upper segments of the deltoid and pectoralis muscles. Its thin muscle fibers cross over the clavicle and proceed obliquely superiorly, laterally and medially over the neck. The platysma muscle fibers thin out anteriorly and attach just behind the symphysis menti. On the lateral side, the muscle fibers pass over the mandible, and some fibers insert into the bone, and others fibers merge in the subcutaneous tissues. Most of the platysma muscle fibers start to thin as they traverse the superior aspect of the lower face and merge or blend in with the muscles around the angle and lower part of the oral cavity.[1]

The actual functional role of platysma is still a topic of some debate. When stimulating the platysma, it may produce wrinkling of the skin surface on the neck. In some cases, it may create a slight depression of the skin of the mandible. In other individuals, it may cause slight drooping of the lower lip and angle of the mouth. However, it is worth noting that the platysma plays a minor role in lip depressor function, which is chiefly performed by the two depressor muscles, namely, the depressor anguli oris and the depressor labii inferioris.[2]

Embryology

The development of the platysma begins in weeks 9 and 10 of gestation by arising from the cervical lamina along with the superficial musculoaponeurotic system.[3] By week 17, the platysma is identifiable at its insertion point on the mandible. At this time, adipose and connective tissue begin to fill the space between the platysma and capsule propia of the parotid; this creates the parotid fascia.[3]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The blood supply to the platysma is from branches of the external carotid artery. The blood supply is rich: even minor trauma can cause bruising.[4] During surgery, hemostasis of the platysma layer is essential before proceeding. Otherwise, constant bleeding can obscure the surgical field. The lymphatic drainage of the platysma is by superficial lymph nodes of the corresponding soft tissue and is irregular as it spans the entire distance of the neck and portions of the face.[5][6]

Nerves

Because the platysma is a muscle of facial expression, its innervation is via the facial nerve (cranial nerve VII). The facial nerve has several main branches: the temporal, zygomatic, buccal, marginal mandibular, and cervical branches.[7] The primary innervation of the platysma is by the cervical branch; however, there are instances of aberrant innervation to some muscle fibers by the marginal mandibular branch. This branch of the facial nerve courses deep to the superior aspect of the platysma inferior to the mandible.[8]

The supraclavicular nerves pierce the inferior portion of the platysma muscle superior to the clavicle. These are pure sensory nerves and provide sensation to the lower neck and upper chest.[9]

Muscles

The platysma, innervated by the facial nerve, is a thin, sheet-like voluntary muscle.

Origin: the muscle has a broad origin with fibers arising from the fascia of the upper thorax including the clavicle, acromial region, pectoralis major and deltoid muscles.

Course: Its fibers run superiorly and medially from the deltoid and pectoral region in a rostral-caudal direction.

Insertion: the muscle inserts on the mandible, the cheek skin, the commissure of the mouth, the orbicularis oris muscle, to the posterior border of the depressor anguli oris muscle, and in some cases higher as high as the orbicularis oculi muscle. This muscle only has a small bony insertion, which is on the anterior third of the mandible.

Anatomical Variations: in 75%, the medial fibers in the submental area interdigitate with the contralateral platysma muscle for up to 1 to 2 cm below the chin. In 15%, the muscle fibers interdigitate all the way down to the thyroid cartilage, and in 10% the medial platysmal fibers do not interdigitate.

Function: contraction of the muscle causes elevation of the neck with accentuation of the platysmal bands and also lowers the midfacial tissues, including the lower lids and midface with deepening of the malar and nasolabial folds. It also lowers the mandible, thereby making the neck shorter and wider. This type of contracture conveys the emotion of surprise, horror, or disgust.

The striated muscle of the platysma can vary in thickness depending on gender, age, and size. In surgeries or dissections of the elderly or malnourished, the platysma can be indistinguishable from the overlying adipose.[6] Muscles immediately deep to the platysma muscle are the sternocleidomastoid muscle and the digastric muscle. Medially, the first layer of strap muscles is encountered covering the larynx and thyroid.[10]

Physiologic Variants

There are many variations in the distribution and origin of the platysma muscle fibers. In some people, the muscle may be absent in some parts of the neck or be very thin. In other cases, the fibers may end at the mental bone superiorly. Very rarely the platysma muscle fibers may be seen as high as the zygomaticus or the margins of the orbicularis oris muscles.[11][6]

Surgical Considerations

In the neck, after making a skin incision, one finds the superficial platysma muscle fibers. On the lateral side of the neck, just underneath the platysma is the external jugular vein which can be seen descending from the angle of the mandible and passing just underneath the clavicle. Similarly, superficial to the sternocleidomastoid muscle and deep to the platysma on the lateral side of the neck is the great auricular nerve and the cervical cutaneous nerves. These nerves provide sensation to the skin overlying parotid, mastoid, and external ear and the skin on the lateral neck, respectively. Superiorly, the most critical structure immediately deep to the platysma muscle is the marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve. It originates at the stylomastoid foramen with the other branches of the facial nerve and courses approximately 2 cm below the inferior border of the mandible. Following the elevation of a platysmal flap to the level of the mandible, great care should be taken to identify and protect this critical contributor to facial expression.[8]

Many surgical procedures in otolaryngology involving the neck, such as thyroid and parathyroid surgery, neck dissections, and laryngeal surgery, include raising a subplatysmal flap. In doing so, the surgeon can expose the contents of the neck. In people with large body habitus, the neck can be incised with impunity to the level of the platysma muscle due to the absence of any critical structures superficial to it (except for small blood vessels whose bleeding is easily controllable). In those with malnutrition or abnormally frail body habitus, incision to the platysma requires care; ubiquitously thin cervical musculature can be mistaken for platysma, leading the incision to be carried to the sternocleidomastoid and strap muscles and unintentionally damaging essential structures.[6]

The platysma plays a role in facial plastic procedures as well. To prevent wrinkling of the neck, the platysma can be injected with botulinum toxin (botox) to paralyze the neck temporarily therapeutically; by inactivating the function of the platysma muscle, the skin overlying the neck is stretched and wrinkled less often thereby preserving its elasticity and preventing permanent creases. In cosmetic surgery to correct dependent and excess cervical skin, the superior insertion of the platysma muscle is reattached more superiorly near the earlobe, thereby giving the neck a more taught and youthful appearance.[12][6]

The great auricular nerve relative to the platysma muscle:

More than 100000 cervicofacial rhytidectomies are performed in the United States every year. All of the varied techniques described require some degree of skin flap elevation in the neck. Injury to the great auricular nerve is the commonest injury seen in cervicofacial rhytidectomy, occurring in 6 to 7% of cases.[13]

The great auricular nerve runs immediately deep to the platysma and courses over the mid-body of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and divides into anterior and posterior branches. Whereas some authors have given dimensions in centimeters to identify where the great auricular nerve runs on the sternocleidomastoid muscle, cadaver studies have shown that irrespective of the length of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, the great auricular nerve runs at the point which is one-third of the distance from either the mastoid process or the external auditory canal to the sternocleidomastoid muscle origin at the clavicle. Surgeons routinely mark this site so that a careful superficial dissection of the skin of the neck from the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle takes place under direct illuminated vision.

Surgical glide plane

The platysma is the most superficial muscle layer in the face. The platysma in the face has a glide plane beneath it which separates it from the deeper masseter muscle. The platysma is derived from the second branchial arch, the masseter from the first branchial arch.

Surgical significance of the aging platysma

As the platysma thins with age, it is noted that cervical platysmal bands often recur after a traditional facelift procedure where the platysma is "tightened" and fixed to the mastoid fascia. It is thought that the aging, thin platysma is not able to hold well with this technique, thereby explaining the recurrence of cervical laxity and neck bands. To that end, some have proposed that resection of central redundant platysma with a double or triple imbrication and tightening central closure of the platysma will give a better and longer-lasting cervical correction. [14] Longer follow-up is needed to prove this, of course. Experienced surgeons note all too common that even with the most advanced techniques, excellent results erode sooner than one likes. Hence the myriad of techniques and approaches that exist for cervicofacial rhytidectomy. The difficulty of attaining and maintaining an excellent central cervical appearance is also partly to do with the fact that one is changing the contour with surgical approaches that are the farthest from this central neck. A fundamental principle of tissue mobilization and retention is that the further one is from the manipulated site, the less the effect, and possibly, the sooner the recurrence. This situation can present with brow lifts, midface lifts, etc.

Platysma and the sternocleidomastoid muscle

A loose connective tissue layer called the superficial cervical fascia is present between the platysma and the sternocleidomastoid muscle, which allows an easy glide of the platysma over the sternocleidomastoid.

Clinical Significance

Change in the platysma with age:

The platysma becomes thinner and less well defined with age. In youth, the muscles fibers often decussate with fibers from the opposite side. With age, the medial fibers separate. There is a weakening of the muscle and sagging, resulting in typical "platysmal bands." Ptosis of the muscle results in further laxity of neck structures.

Relationship of the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) to the platysma:

Traditionally, the depiction of the platysma was as mainly a cervical muscle with most anatomy textbooks showing only a small extension of the platysma over the mandibular border onto the face, with the SMAS as a distinct facial structure. Recent anatomical and surgical findings indicated that the platysma has a significant facial component and actually extends more superiorly onto the face. The SMAS is a fibro-fatty layer in the face with distinct facial components as described by Mitz and Peyronie in 1976.[15] Research has shown that the platysma extends to more than 50% of the distance between the mandibular angle and the malar eminence (called the mandibular malar line, MML). The SMAS and the platysma, therefore, blend together to a significant extent, and some have proposed that surgeons should treat the two as a composite flap rather than distinct facial and cervical structures, respectively. Indeed, it is probably wise to think of the layer as the superficial musculoaponeurotic system-platysma complex (SMASP) rather than individual sections, especially when addressing these tissues during cervicofacial rhytidectomy and neck lifts.

The Jowl and the Platysma

Mendelson et al have shown that platysmal redundancy makes up the overlying laxity seen in a jowl.[16]

What causes platysmal bands?

Platysmal bands begin to appear in most people by the age of 55 years with worsening over time. There are several theories for the appearance of platysmal bands with age. These include skin laxity, loss of platysmal tone, and detachment of the platysma from deeper attachments. A more recent theory is that the platysma becomes hyperkinetic, making the platysma more prominent (in the form of bands), which secondarily cause skin laxity instead of the other way around. The current thinking is that the anterior platysma bands are created by contracture of these anterior free platysmal fibers because they are not seen in the presence of facial palsy but worsen on the non-paralysed side with time.[17]

Based upon these studies of patients with unilateral facial paralysis, Trevidic et al. have proposed selective denervation of the platysma for the management of platysmal bands.[18]

Media

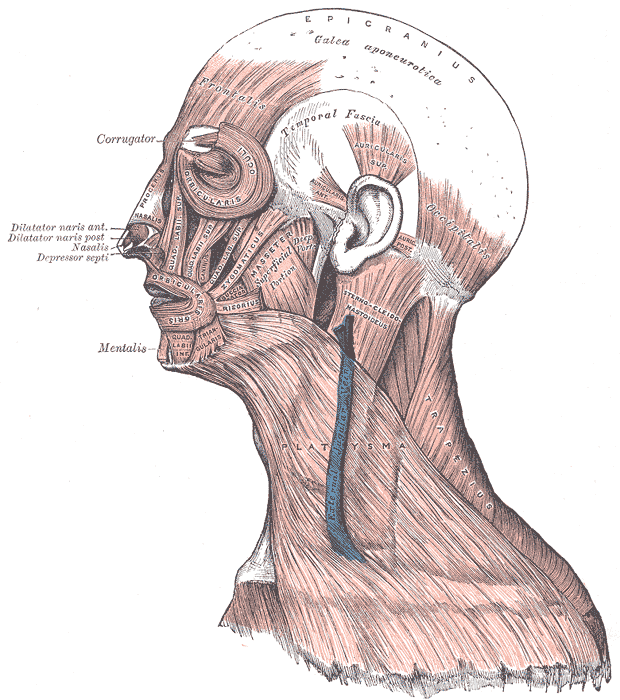

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Muscles of the Head, Face, and Neck. The epicranius, galea aponeurotica, frontalis, temporal fascia, auricularis superior, auricularis anterior, auricularis posterior, occipitalis, sternocleidomastoid, platysma, trapezius, orbicularis oculi, corrugator, procerus, nasalis, dilator naris anterior, dilator naris posterior, depressor septi, mentalis, orbicularis oris, masseter, zygomaticus, and risorius muscles are shown in the image.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Baur DA, Williams J, Alakaily X. The platysma myocutaneous flap. Oral and maxillofacial surgery clinics of North America. 2014 Aug:26(3):381-7. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2014.05.006. Epub 2014 Jun 21 [PubMed PMID: 24958382]

Shadfar S, Perkins SW. Anatomy and physiology of the aging neck. Facial plastic surgery clinics of North America. 2014 May:22(2):161-70. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2014.01.009. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24745379]

De la Cuadra-Blanco C, Peces-Peña MD, Carvallo-de Moraes LO, Herrera-Lara ME, Mérida-Velasco JR. Development of the platysma muscle and the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (human specimens at 8-17 weeks of development). TheScientificWorldJournal. 2013:2013():716962. doi: 10.1155/2013/716962. Epub 2013 Dec 12 [PubMed PMID: 24396304]

Fedok FG, Chaikhoutdinov I, Garritano F. The difficult neck in facelifting. Facial plastic surgery : FPS. 2014 Aug:30(4):438-50. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1383554. Epub 2014 Jul 30 [PubMed PMID: 25076452]

Koroulakis A, Jamal Z, Agarwal M. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Lymph Nodes. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30020689]

Hwang K, Kim JY, Lim JH. Anatomy of the Platysma Muscle. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2017 Mar:28(2):539-542. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000003318. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28027174]

Sakellariou A, Salama A. The use of cervicofacial flap in maxillofacial reconstruction. Oral and maxillofacial surgery clinics of North America. 2014 Aug:26(3):389-400. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2014.05.007. Epub 2014 Jun 26 [PubMed PMID: 24980990]

Huettner F, Rueda S, Ozturk CN, Ozturk C, Drake R, Langevin CJ, Zins JE. The relationship of the marginal mandibular nerve to the mandibular osseocutaneous ligament and lesser ligaments of the lower face. Aesthetic surgery journal. 2015 Feb:35(2):111-20. doi: 10.1093/asj/sju054. Epub 2015 Feb 12 [PubMed PMID: 25681104]

Farrior E, Eisler L, Wright HV. Techniques for rejuvenation of the neck platysma. Facial plastic surgery clinics of North America. 2014 May:22(2):243-52. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2014.01.012. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24745386]

Gordon NA, Adam SI. The deep-plane approach to neck rejuvenation. Facial plastic surgery clinics of North America. 2014 May:22(2):269-84. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2014.01.003. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24745388]

Thomas JR, Dixon TK. Preoperative evaluation of the aging neck patient. Facial plastic surgery clinics of North America. 2014 May:22(2):171-6. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2014.01.004. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24745380]

Khan HA, Bagheri S. Surgical anatomy of the superficial musculo-aponeurotic system (SMAS). Atlas of the oral and maxillofacial surgery clinics of North America. 2014 Mar:22(1):9-15. doi: 10.1016/j.cxom.2013.11.005. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24581561]

Lefkowitz T, Hazani R, Chowdhry S, Elston J, Yaremchuk MJ, Wilhelmi BJ. Anatomical landmarks to avoid injury to the great auricular nerve during rhytidectomy. Aesthetic surgery journal. 2013 Jan:33(1):19-23. doi: 10.1177/1090820X12469625. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23277616]

Citarella ER, Condé-Green A, Sinder R. Triple suture for neck contouring: 14 years of experience. Aesthetic surgery journal. 2010 May-Jun:30(3):311-9. doi: 10.1177/1090820X10374096. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20601554]

Mitz V, Peyronie M. The superficial musculo-aponeurotic system (SMAS) in the parotid and cheek area. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1976 Jul:58(1):80-8 [PubMed PMID: 935283]

Mendelson BC, Freeman ME, Wu W, Huggins RJ. Surgical anatomy of the lower face: the premasseter space, the jowl, and the labiomandibular fold. Aesthetic plastic surgery. 2008 Mar:32(2):185-95. doi: 10.1007/s00266-007-9060-3. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18183455]

Trévidic P, Criollo-Lamilla G. Platysma Bands: Is a Change Needed in the Surgical Paradigm? Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2017 Jan:139(1):41-47. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000002894. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27627054]

Trévidic P, Criollo-Lamilla G. Surgical Denervation of Platysma Bands: A Novel Technique in Rhytidectomy. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2019 Nov:144(5):798e-802e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000006148. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31373989]