Introduction

The clavicle is a sigmoid-shaped long bone with a convex surface along its medial end when observed from cephalad position. It serves as a connection between the axial and appendicular skeleton in conjunction with the scapula, and each of these structures forms the pectoral girdle.[1] Though not as large as other supporting structures in the body, clavicular attachments allow for significant function and range of motion of the upper extremity as well as protection of neurovascular structures posteriorly. Each part of this long bone has a purpose in regards to its attachments that affects the overall physiology of the pectoral girdle.

Medially, the clavicle articulates with the manubrial portion of the sternum, forming the sternoclavicular joint (SC joint). This joint, surrounded by a fibrous capsule, contains an intra-articular disc in between the clavicle and the sternum. Superiorly, the interclavicular ligament connects the ipsilateral and contralateral clavicle, together providing further stability.[2]

Laterally, the clavicle articulates with the acromion, forming the acromioclavicular ligament (AC joint). The surrounding area provides an attachment for the joint capsule of the shoulder. This joint, like the SC joint, is also lined by fibrocartilage and contains an intra-articular disc. The three main ligaments to support this joint are the AC ligament, the coracoclavicular ligament (CC), and the coracoacromial ligament (CA).[3]

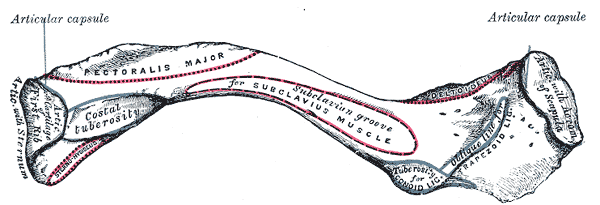

The actual shaft of the clavicle is clinically divided into two parts clinically: medial two-thirds and lateral third. These locations are used to properly identify where muscles are attached. The medial two-thirds has an attachment site for the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle and subclavius muscle along the subclavian groove superiorly and inferiorly, respectively. The anterior surface is an attachment for the pectoralis major and the posterior for the sternohyoid muscle. The costal tuberosity, which is where the costoclavicular ligament inserts and supports the SC joint, is also found on the inferior surface.[4] The lateral third of the clavicle serves as attachments for the deltoid and trapezius muscles anteriorly and posteriorly, respectively. Inferiorly the conoid and trapezoid components of the CC ligament provide stability between the clavicle and the coracoid process of the scapula.

The clavicle happens to be one of the most commonly fractured bones in the human body; fracture can be as a result of direct contact or force transmission from falling onto an outstretched hand. Depending on the level of displacement of the fracture, surgery may be indicated, and proper management is determined on an individual basis due to differentiating factors surrounding such injury.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

Although small, the clavicle allows for optimal function of the upper extremity as well as protects the upper extremity by dispersing the amount of force transmitted from direct contact. The positioning of the clavicle also keeps the extremity far enough away from the thorax, allowing for the range of motion (ROM) of the shoulder to be unimpeded. Its strut-like mechanics allow the scapula to glide smoothly along the posterior wall which is critical for full upper extremity motion.[5] The anatomical location also protects neurovascular structures, including the brachial plexus, subclavian artery, and subclavian vein which, if disrupted, would greatly increase morbidity.[6]

Embryology

The clavicle, interestingly, is the first bone to begin ossification during embryologic development and is a derivative of the lateral mesoderm. The medial and lateral ends of the clavicle undergo different processes of ossification. The medial end undergoes formation via endochondral ossification. Endochondral ossification of a bony structure is preceded by a cartilaginous model constructed by chondrocytes before mineralization and ossification. The lateral end, on the contrary, forms via intramembranous ossification which constitutes woven bone formed directly without cartilage. In both cases, the structure is remodeled in a way that the result is lamellar bone. Despite being one of the first bones to begin ossification, it is one of the last to complete this process, and growth plates may not close until between the twentieth to twenty-fifth year of life.[7][8]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Although classified as a long bone, the clavicle (in most cases) does not have a medullary cavity like its long bone counterparts. Previous studies have shown periosteal arterial blood supply to the bony structure but no central nutrient artery (a.). The suprascapular a., thoracoacromial a., and the internal thoracic a. (mammalian a.) have all been found to provide arterial supply to the clavicle.[9]

Nerves

Controversy surrounds the primary sensory innervation of the clavicle. Anesthetizing studies following clavicular fracture have suggested there may be involvement individually or in a combination of the supraclavicular nerve (n.), subclavian n., and long thoracic/suprascapular n.[10] A common anatomical variation is a perforating branch of the supraclavicular n. that passes in the superior surface of the clavicle. Post-mortem studies have revealed insertion of the nerve in bony tunnels or grooves that would prove susceptible to injury and may explain entrapment neuropathy following clavicular fracture.[11]

Muscles

The clavicle has multiple attachments for musculature that should be considered anatomically.

- Superior surface: The anterior deltoid originates on the anterior aspect and assists in flexion of the shoulder while one of the insertion sites for the trapezius muscle is located at the posterior aspect. The trapezius predominantly is responsible for stabilizing the scapula.[12]

- inferior surface: The subclavius muscle resides in the subclavian groove of the clavicle and functions to depress the shoulder as well as pull the clavicle anteroinferiorly. The coracoacromial ligament is located laterally and provides support from the coracoid residing below. The medial component of the CA ligament is the conoid ligament which inserts onto the conoid tubercle, and the lateral component is the trapezoid ligament which inserts onto the trapezoid line.

- Anterior surface: The clavicular part of the pectoralis major muscle originates from the medial clavicle anteriorly. The clavicular head contributes to flexion, horizontal adduction, and inward rotation of the humerus.

- Posterior surface: As mentioned, the trapezius inserts posterosuperior on the clavicle. The clavicular head of the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) also has a similar location but is found along the medial third of the clavicle. The SCM, when contracting alone, causes the head to rotate to the opposite side and laterally side bend ipsilaterally. When both SCM contract, this causes head flexion.

The sternohyoid muscle has fibers originating inferomedially along the posterior surface of the clavicle in addition to the manubrium and posterior sternoclavicular ligament. Contraction of the sternohyoid causes hyoid bone depression.

Physiologic Variants

Compared to other long bones, the clavicle has shown to exhibit varying features. Thickness and length can both vary depending on the sex, with males having longer and thicker bone morphology than females. Males also have a greater degree of curvature in the bone compared to females. Cadaveric studies also revealed left clavicles were substantially longer than the contralateral.[13] A rare, but clinically relevant genetic disease, cleidocranial dysplasia, can present with absent or partially absent clavicles bilaterally. Dental abnormalities, delayed fontanel closure, and cranial sutures that have failed to fuse are other features that can be present in this disease.[14]

Surgical Considerations

One of the most common fractures to occur is a clavicular fracture, more typically in the middle third of the bone. While most medial and lateral fractures can be managed non-operatively if they remain stable, mid-shaft fractures can potentially have a higher degree of displacement with an increased incidence of malunion or non-union. Depending on the displacement and possible shortening of the involved fragments, surgery may be warranted. Additionally, neurovascular compromise may also be an indication for operative management. Pediatric injury typically occurs in physeal regions of the clavicle, and due to the healing potential of these regions, non-operative treatment can be pursued.[15]

Operative management has shown to improve short-term functional outcomes; however, long-term shoulder function difference compared to non-operative management has proven unremarkable. Open reduction with internal fixation using plate and screws as well as intramedullary nails have been used to reduce these fractures.[16] Increased patient satisfaction and earlier return to physical activity have been seen with surgical management when compared to the non-operative approach. Cost-effectiveness was also surprisingly advantageous for operative patients. Current recommendations suggest a patient-tailored approach when considering surgery which may involve multiple parameters.[17]

Clinical Significance

The mid-clavicular line is a landmark on the clavicle that is used for multiple reasons. This landmark provides a general location for cardiac apex beat as well as appreciating the liver size. It also can be used to locate the gallbladder which is located between the mid-clavicular line and transpyloric plane. Accurate location assessment can vary, however, depending on the user.[18]

- Clavicle fractures are responsible for 10% of all fractures and are the most acute of issues when dealing with injuries of the clavicle.[19] Depending on comminution, displacement, and shortening, surgery may be warranted. The level of superior displacement of the medial fragment seen in midshaft fractures may be due to SCM tension leading to further instability. The injury typically occurs due to trauma, such as falling directly on the shoulder laterally in 87% of cases. The injury also may be a result of falling outward onto an outstretched hand or due to contact directed medially onto the clavicle.[19]

- AC joint (ACJ) dislocation is common in contact sports and represents 9% of all traumatic shoulder girdle injuries [20]. The joint injury can be appreciated via X-ray imaging and is classified into six types. The injury severity increases with injury type and is dependent on the amount of gapping between acromioclavicular articulation.[21]

- Type I and II injuries are managed nonoperatively. The former manifest solely as ACJ tenderness but no instability. Type II injuries exhibit horizontal instability only, as the ACJ is disrupted and coracoclavicular distance is increased by less than 25% compared to the contralateral extremity.

- Type III injuries are often managed nonoperatively as well, albeit slightly more controversial. For example, as surgical techniques have improved over the years, a survey of 28 Major League Baseball team orthopedic surgeons resulted in 72% (20/28) reporting nonoperative treatment as the preferred management modality [22]. Interestingly enough, the aforementioned study from 2018 closely echoed the previous classic report 20 years earlier from McFarland and colleagues, when 69% of team physicians reported favoring nonoperative management of type III AC separations [23]. Thirty years earlier, however, there was an overwhelming preference for treating acute, complete ACJ separation with surgical repair. A study from the 1970s by Powers and Bach consisted of a163 chairmen-survey of United States orthopedic programs, with 92% advocated for surgical treatment [24].

- Type IV injuries through VI are typically managed with surgery. [25] Type IV consists of lateral clavicular posterior displacement through the trapezial fascia. Type V is an increase in CC distance greater than 100% compared to the contralateral. Type VI consists of inferior dislocation of the lateral clavicle (in the subacromial or subcoracoid positions)[25].

- AC joint osteoarthritis has multiple etiologies including degenerative, posttraumatic, septic, and inflammatory arthritis. Being the most common disorder of the AC joint, it can be quite debilitating for patients in their daily activities, especially with overhead activity. Clinical management can consist of the use of anti-inflammatory medication, intra-articular injections, and physical therapy. If symptoms persist, some patients may be candidates for AC joint resection.[26]

- SC joint injuries can also occur; however, they are less common. Anterior dislocations can occur with an anterolateral loading of the distal clavicle; posterior dislocations occur with posterolateral loading. An even less common mechanism of posterior SC joint dislocation can be due to significant posteriorly directed force to the medial head of the clavicle. Females with ligamentous laxity have a higher incidence of SC joint injuries and can also be associated with trapezius nerve palsy.[27]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Javed O, Maldonado KA, Ashmyan R. Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Muscles. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29494017]

Tubbs RS, Loukas M, Slappey JB, McEvoy WC, Linganna S, Shoja MM, Oakes WJ. Surgical and clinical anatomy of the interclavicular ligament. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2007 Jul:29(5):357-60 [PubMed PMID: 17563831]

Wong M, Kiel J. Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Acromioclavicular Joint. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29763033]

Tubbs RS, Shah NA, Sullivan BP, Marchase ND, Cömert A, Acar HI, Tekdemir I, Loukas M, Shoja MM. The costoclavicular ligament revisited: a functional and anatomical study. Romanian journal of morphology and embryology = Revue roumaine de morphologie et embryologie. 2009:50(3):475-9 [PubMed PMID: 19690777]

Hsu JE, Hulet DA, McDonald C, Whitson A, Russ SM, Matsen FA 3rd. The contribution of the scapula to active shoulder motion and self-assessed function in three hundred and fifty two patients prior to elective shoulder surgery. International orthopaedics. 2018 Nov:42(11):2645-2651. doi: 10.1007/s00264-018-4027-3. Epub 2018 Jul 9 [PubMed PMID: 29987556]

Okwumabua E, Thompson JH. Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Axillary Nerve. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29630264]

Vieth V, Schulz R, Brinkmeier P, Dvorak J, Schmeling A. Age estimation in U-20 football players using 3.0 tesla MRI of the clavicle. Forensic science international. 2014 Aug:241():118-22. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2014.05.008. Epub 2014 May 21 [PubMed PMID: 24908196]

Schmidt S, Ottow C, Pfeiffer H, Heindel W, Vieth V, Schmeling A, Schulz R. Magnetic resonance imaging-based evaluation of ossification of the medial clavicular epiphysis in forensic age assessment. International journal of legal medicine. 2017 Nov:131(6):1665-1673. doi: 10.1007/s00414-017-1676-5. Epub 2017 Sep 9 [PubMed PMID: 28889331]

Knudsen FW, Andersen M, Krag C. The arterial supply of the clavicle. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 1989:11(3):211-4 [PubMed PMID: 2588097]

Tran DQ, Tiyaprasertkul W, González AP. Analgesia for clavicular fracture and surgery: a call for evidence. Regional anesthesia and pain medicine. 2013 Nov-Dec:38(6):539-43. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000012. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24121609]

Natsis K, Totlis T, Chorti A, Karanassos M, Didagelos M, Lazaridis N. Tunnels and grooves for supraclavicular nerves within the clavicle: review of the literature and clinical impact. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2016 Aug:38(6):687-91. doi: 10.1007/s00276-015-1602-9. Epub 2015 Dec 24 [PubMed PMID: 26702936]

Bordoni B, Reed RR, Tadi P, Varacallo M. Neuroanatomy, Cranial Nerve 11 (Accessory). StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29939544]

Bernat A, Huysmans T, Van Glabbeek F, Sijbers J, Gielen J, Van Tongel A. The anatomy of the clavicle: a three-dimensional cadaveric study. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2014 Jul:27(5):712-23. doi: 10.1002/ca.22288. Epub 2013 Oct 21 [PubMed PMID: 24142486]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceModgil R, Arora KS, Sharma A, Mohapatra S, Pareek S. Cleidocranial Dysplasia: Presentation of Clinical and Radiological Features of a Rare Syndromic Entity. Mymensingh medical journal : MMJ. 2018 Apr:27(2):424-428 [PubMed PMID: 29769514]

van der Meijden OA, Gaskill TR, Millett PJ. Treatment of clavicle fractures: current concepts review. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery. 2012 Mar:21(3):423-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.08.053. Epub 2011 Nov 6 [PubMed PMID: 22063756]

Vlček M, Niedoba M, Jakubička J, Pech J, Kalvach J. [Surgical treatment of midshaft clavicular fractures using intramedullary nail]. Rozhledy v chirurgii : mesicnik Ceskoslovenske chirurgicke spolecnosti. 2018 Spring:97(4):176-188 [PubMed PMID: 29726264]

Hoogervorst P, van Schie P, van den Bekerom MP. Midshaft clavicle fractures: Current concepts. EFORT open reviews. 2018 Jun:3(6):374-380. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.3.170033. Epub 2018 Jun 20 [PubMed PMID: 30034818]

Naylor CD, McCormack DG, Sullivan SN. The midclavicular line: a wandering landmark. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne. 1987 Jan 1:136(1):48-50 [PubMed PMID: 2947672]

Bentley TP, Hosseinzadeh S. Clavicle Fractures. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29939669]

Mazzocca AD, Arciero RA, Bicos J. Evaluation and treatment of acromioclavicular joint injuries. The American journal of sports medicine. 2007 Feb:35(2):316-29 [PubMed PMID: 17251175]

Eschler A, Rösler K, Rotter R, Gradl G, Mittlmeier T, Gierer P. Acromioclavicular joint dislocations: radiological correlation between Rockwood classification system and injury patterns in human cadaver species. Archives of orthopaedic and trauma surgery. 2014 Sep:134(9):1193-8. doi: 10.1007/s00402-014-2045-1. Epub 2014 Jul 4 [PubMed PMID: 24993589]

Liu JN, Garcia GH, Weeks KD, Joseph J, Limpisvasti O, McFarland EG, Dines JS. Treatment of Grade III Acromioclavicular Separations in Professional Baseball Pitchers: A Survey of Major League Baseball Team Physicians. American journal of orthopedics (Belle Mead, N.J.). 2018 Jul:47(7):. doi: 10.12788/ajo.2018.0051. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30075044]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMcFarland EG, Blivin SJ, Doehring CB, Curl LA, Silberstein C. Treatment of grade III acromioclavicular separations in professional throwing athletes: results of a survey. American journal of orthopedics (Belle Mead, N.J.). 1997 Nov:26(11):771-4 [PubMed PMID: 9402211]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePowers JA, Bach PJ. Acromioclavicular separations. Closed or open treatment? Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 1974 Oct:(104):213-23 [PubMed PMID: 4411824]

Stucken C, Cohen SB. Management of acromioclavicular joint injuries. The Orthopedic clinics of North America. 2015 Jan:46(1):57-66. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2014.09.003. Epub 2014 Oct 11 [PubMed PMID: 25435035]

Menge TJ,Boykin RE,Bushnell BD,Byram IR, Acromioclavicular osteoarthritis: a common cause of shoulder pain. Southern medical journal. 2014 May [PubMed PMID: 24937735]

Kiel J, Ponnarasu S, Kaiser K. Sternoclavicular Joint Injury. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29939671]