Introduction

The official Terminologia Anatomica name of the appendix is "Appendix Vermiformis". The appendix, a true diverticulum arising from the posteromedial cecal border, is located in close proximity to the ileocecal valve. The base of the appendix can be reliably located near the convergence of the taeniae coli at the tip of the cecum. The term vermiform is Latin for worm-like[1] and ascribes to its long, tubular architecture. In contrast to an acquired diverticulum, it is a true diverticulum of the colon and contains all of the colonic layers: mucosa, submucosa, longitudinal and circular muscularis propria and serosa. The histological distinction between the colon and the appendix depends upon the presence of B and T lymphoid cells in the appendicular mucosa and submucosa.[2]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The appendix can have a variable length, ranging from 5 to 35 cm, an average of 9 cm[3]. The function of the appendix has traditionally been a topic of debate. The neuroendocrine cells in the mucosa produce amines and hormones to assist with various biological control mechanisms, whereas the lymphoid tissue is involved with the maturation of B lymphocytes and the production of IgA antibodies[1]. There is no clear evidence for its function in humans. The presence of gut-associated lymphoid tissue in the lamina propria has led to the belief that it serves a function in immunity, although the specific nature of this has never been identified. As a result, the organ has mostly maintained its reputation as a vestigial organ. However, as the recent understanding of gut immunity has improved, a theory that the appendix is a “safe house” for symbiotic gut microbes[4] has emerged. Extreme bouts of diarrhea that may clear the gut of commensal bacteria can be replaced by that contained in the appendix. This suggests an evolutionary advantage for the maintenance of the vermiform appendix and weakens the theory that the organ is vestigial.[5]

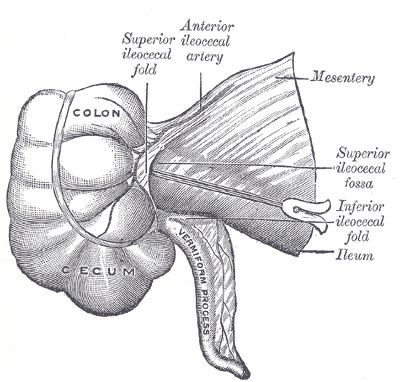

Embryology

The appendix arises from the midgut. The cecal diverticulum appears at week 6 and is the precursor of the cecum and vermiform appendix. The appendix is histologically visible by 8 weeks of gestation. With the developmental elongation of the colon, the cecum and appendix undergo medial rotation(along with the midgut) and descend into the right lower abdomen. As the appendix is pushed ahead of the cecum, it adopts various positions, seemingly at random. During weeks 14 and 15, the mucosa develops lymphoid tissue, lending to its proposed function in immunity.

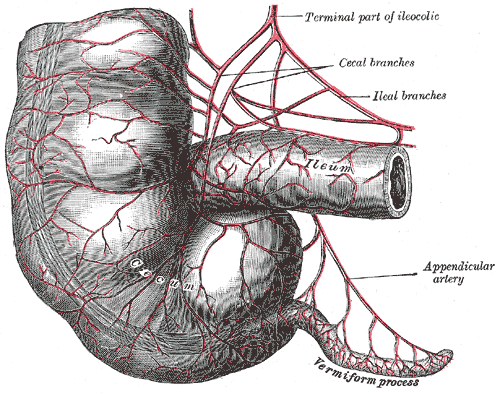

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The appendicular artery, a terminal branch of the ileocecal artery, supplies blood to the appendix. This artery is a branch of the superior mesenteric artery, coinciding with its origin as a midgut derivative. Lymph from both the appendix and cecum drain into the ileocolic lymph nodes. However, while drainage from the cecum is via several intermediate mesenteric lymph nodes, the appendix drains through a single intermediate node. From the ileocolic lymph nodes, drainage proceeds to the superior mesenteric nodes.[2]

Nerves

The autonomic innervation of the appendix arises from the superior mesenteric plexus. Afferent sensory fibers from the appendix are carried on the sympathetic nerve fibers to enter the spinal cord at T10 which corresponds to the umbilical dermatome.

Physiologic Variants

While the location of the appendicular orifice at the base of the cecum is a consistent anatomical feature, the position of its tip is not. Variations in the position include retrocecal(but intraperitoneal), subcecal, pre-ileal and post-ileal, pelvic and as far as into the hepatorenal recess. In addition, factors such as posture, respiration, and distention of adjacent bowels can influence the position of the appendix. The retrocecal position is by far the most common. This can cause clinical confusion in diagnosing appendicitis as variations in position can produce different symptoms. Rarely agenesis of the appendix as well as duplication or triplication has been described in the literature. With advancing pregnancy, the enlarging uterus pushes the appendix cephalad, so much so that, by the end of the third trimester the pain of appendicitis may be perceived in the right upper quadrant.

Surgical Considerations

Appendectomy for acute appendicitis is one of the most frequent indications for emergent abdominal surgery. An important anatomical landmark for surgeons performing appendectomy is the convergence of the taeniae coli which marks the base of the appendix. By following them inferiorly, the appendix can be located and resected.

Clinical Significance

Acute appendicitis follows pathogenesis similar to that of other hollow viscous organs and is thought to be most often caused by obstruction. A fecalith, or sometimes a gallstone, tumor, or worms obstructs the appendiceal orifice, causing increased intraluminal pressure and compromised venous outflow. In the young, obstruction is more often caused by lymphoid hyperplasia. The appendix receives its blood supply from the appendicular artery, which is an end artery. As intraluminal pressure exceeds the perfusion pressure, ischemic injury results, encouraging bacterial overgrowth and triggering an inflammatory response. This becomes a surgical emergency because perforation of the inflamed appendix can leak bacterial contents into the abdominal cavity.[6]

As the appendiceal wall becomes inflamed, visceral afferent fibers are stimulated. These fibers enter the spinal cord at T8-T10, producing the classic diffuse periumbilical pain and nausea seen at the onset of appendicitis. As inflammation progresses, the parietal peritoneum is irritated, stimulating somatic nerve fibers and producing more localized pain. The localization depends on the position of the tip of the appendix. For example, a retrocecal appendix can produce right flank pain. Extending the patient’s right hip can elicit this pain. Pain produced by stretching the iliopsoas muscle due to hip extension with the patient in the left lateral decubitus position is known as “psoas sign.” Another classic finding in acute appendicitis is McBurney’s sign. This is elicited by palpation of the abdominal wall at the McBurney's point(two-thirds the distance from the umbilicus to the right anterior superior iliac spine) when pain is elicited. Unfortunately, these signs and symptoms are not always present, making clinical diagnosis difficult. The clinical picture often includes nausea, vomiting, low-grade fever, and a slightly elevated white count.

In addition to acute appendicitis, cancer of the appendix is another clinical concern. The most common of these is a carcinoid tumor. This neoplasm often forms a 2 cm to 3 cm mass at the distal tip. Carcinoid tumors are of neuroendocrine origin and can secrete serotonin or other vasoactive substances. Carcinoid syndrome can arise as a result and produce symptoms such as flushing, diarrhea, wheezing, or right-sided valvular heart disease. Because most of these arise in the distal one-third, they rarely cause an obstruction and can remain asymptomatic. However, 10% of neuroendocrine tumors arise at the base of the appendix and can cause appendicitis.

Appendiceal adenocarcinoma is another possible neoplasm of the appendix; its clinical presentation is often indistinguishable from that of acute appendicitis as it also causes obstructive pathology. It is often seen in the elderly and treatment involves a surgical approach involving either a simple appendectomy or a right colectomy.

Other Issues

Appendicitis is a frequent presentation to the emergency department and all nurses should be familiar with the disorder. It is the triage nurse who is responsible for expediting the admission of the patient to the emergency department so that the patient can be seen promptly by the staff. Once the diagnosis is confirmed, patients are kept NPO, started on antibiotics and hydrated. Surgery is usually done the same day. Nurses also play a vital role in the monitoring of the patient post-operatively. Appendectomy can be performed either laparoscopically or via a small abdominal incision. Data indicate that the laparoscopic procedure is associated with less pain and a faster recovery. However, the long term outcomes are similar.[7]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Deshmukh S, Verde F, Johnson PT, Fishman EK, Macura KJ. Anatomical variants and pathologies of the vermix. Emergency radiology. 2014 Oct:21(5):543-52. doi: 10.1007/s10140-014-1206-4. Epub 2014 Feb 26 [PubMed PMID: 24570122]

Kahai P, Mandiga P, Wehrle CJ, Lobo S. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Large Intestine. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29261962]

Schumpelick V, Dreuw B, Ophoff K, Prescher A. Appendix and cecum. Embryology, anatomy, and surgical applications. The Surgical clinics of North America. 2000 Feb:80(1):295-318 [PubMed PMID: 10685154]

Randal Bollinger R, Barbas AS, Bush EL, Lin SS, Parker W. Biofilms in the large bowel suggest an apparent function of the human vermiform appendix. Journal of theoretical biology. 2007 Dec 21:249(4):826-31 [PubMed PMID: 17936308]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceXiang H, Han J, Ridley WE, Ridley LJ. Vermiform appendix: Normal anatomy. Journal of medical imaging and radiation oncology. 2018 Oct:62 Suppl 1():116. doi: 10.1111/1754-9485.59_12784. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30309110]

Childers CP, Dworsky JQ, Maggard-Gibbons M, Russell MM. The contemporary appendectomy for acute uncomplicated appendicitis in adults. Surgery. 2019 Mar:165(3):593-601. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2018.09.009. Epub 2018 Oct 29 [PubMed PMID: 30385123]

Buitrago G, Junca E, Eslava-Schmalbach J, Caycedo R, Pinillos P, Leal LC. Clinical Outcomes and Healthcare Costs Associated with Laparoscopic Appendectomy in a Middle-Income Country with Universal Health Coverage. World journal of surgery. 2019 Jan:43(1):67-74. doi: 10.1007/s00268-018-4777-5. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30145672]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence