Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Foot Cuboid Bone

Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Foot Cuboid Bone

Introduction

The cuboid is one of seven tarsal bones of the foot. The cuboid is located laterally on the distal row of the tarsus and makes up the center of the lateral column of the foot. The bone is a cubical shape with prominence on the plantar surface, also known as the tuberosity of the cuboid. The cuboid provides a groove for the peroneus longus muscle tendon as it reaches to insert in the first metatarsal and medial cuneiform bones. The only muscle to attach to the cuboid is the tibialis posterior.[1]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The cuboid bone has a cub-like shape and is positioned between the calcaneus and the fourth and fifth metatarsals to form the lateral column of the foot. The cuboid has five articular surfaces that contribute to the intrinsic movement of the foot. These articulations include the calcaneus posteriorly, the fourth and fifth metatarsals anteriorly, and the navicular and lateral cuneiform medially. The cuboid bone is stabilized in the middle of the lateral column by many ligaments, including the calcaneocuboid, cuboideo-navicular, cuboideo-metatarsal, and long plantar ligaments. The cuboid bone serves as one of the bony attachments for the tibialis posterior tendon. The peroneal sulcus is a groove located on the lateral aspect of the cuboid through which the peroneus longus tendon passes before inserting on the lateral base of the first metatarsal and medial cuneiform. This arrangement allows the cuboid to serve as a pulley during contraction of the peroneus longus muscle. The cuboid provides inherent stability to the foot by its role as the supporting element of the static and rigid lateral column of the foot. Though the cuboid bone is not directly involved in weight-bearing, it is subjected to stress forces during standing and ambulation, and its contribution is essential to the mobility of the lateral column of the foot.[2][3][4][5]

Embryology

The limb buds appear around 4 weeks of age. The developmental route of the skeleton begins with the formation of a mesenchymal template, transforming cartilage by chondrification, and then ossification to form bone. The bone shape changes occur during this process.[6][7]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The cuboid receives its blood supply from the lateral plantar artery, a branch of the posterior tibial artery. The lateral plantar artery anastomosis with the medial plantar artery, which allows for adequate blood supply and bone consolidation following a cuboid fracture.[1][8]

The lymphatic flow follows the vasculature and flows up the lower extremity to gather in popliteal and femoral collectors.[9]

Nerves

The cuboid bone is at the dorsal superficial and deep plantar part of the foot.

The sensory nerves that are responsible for the dermatomes of the same areas are the superficial peroneal nerve and the lateral plantar nerve.[10][11]

Muscles

The tibialis posterior is the only muscle to attach to the cuboid bone. The tibialis posterior muscle originates from the posterior compartment of the lower leg. It travels distally as the tibialis posterior tendon to insert on several tarsal bones, including the underside of the cuboid bone. The tibialis posterior is the principal inverter and secondary plantar flexor of the foot. Part of the flexor hallucis brevis muscle arises from the plantar aspect of the cuboid. The flexor hallucis brevis aids in the flexion of the great toe.[12]

Physiologic Variants

Tarsal coalition is a congenital abnormality in which there is an aberrant union between two or more tarsal bones in the foot. The cuboid-navicular coalition is an especially rare type of tarsal coalition that can occur. They represent less than 1% of all tarsal coalitions. The most likely etiology of tarsal coalitions is a genetic mutation that results in the absence of differentiation and segmentation of primitive mesenchyme. The cuboid-navicular tarsal coalition is usually asymptomatic. Still, the clinician can discover it due to the onset of pain symptoms in the cuboid-navicular area during times of stress and exercise. The diagnosis of this coalition is possible with radiographic evidence. However, the diagnosis can be difficult as radiographic findings are often subtle. Advanced imaging studies may be necessary for further evaluation of the coalition. The clinician can initiate treatment in symptomatic cases. Treatment is usually conservative and involves measures such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, steroid injections, physical therapy, and/or orthotics.[13][14]

Surgical Considerations

A cuboid-navicular coalition deformity that has exhausted conservative treatment is treatable with surgical resection and interposition of an adipose graft.[13]

Surgical intervention is a consideration for cuboid fractures in which lateral column length and/or joint congruency have suffered compromise. The purpose of surgery in these cases is to restore lateral column length and anatomy of surrounding joints to avoid functional and biomechanical consequences and prevent adverse effects such as stiffness, arthritis, and deformity. Surgical techniques of cuboid fractures include external fixators, open reduction and internal fixation, bone grafting, and/or joint fusion.[15][2]

Clinical Significance

“Cuboid syndrome” is a condition that involves disruption or subluxation of the calcaneocuboid joint; this occurs as a result of overuse, excessive pronation, and/or ankle sprains. Disruption of the CC joint leads to an abnormal cuboid position, which can irritate surrounding ligaments, the joint capsule, and peroneus longus tendon. Symptoms of the cuboid syndrome are similar to symptoms found in a ligament sprain. These include lateral foot pain, swelling, ecchymosis, and/or erythema. Patients may also have limited active and passive range of motion of their foot and/or ankle. Diagnosis of cuboid syndrome is clinical, and other pathologies such as fractures should be ruled out. Treatment is conservative and includes cuboid manipulation techniques, physical therapy, and cuboid padding.[16]

Cuboid fractures are rare due to the anatomy and protected location in the midfoot. They can occur with forced plantar flexion and abduction of the foot, and usually, are seen in combination with other foot fractures and dislocations. Cuboid fractures can be the result of a direct impact injury such as a heavy object falling on the dorsum of the foot, or an avulsion injury involving any of the cuboid’s ligamentous attachments. An isolated cuboid fracture, also known as a “nutcracker fracture,” can occur when severe abduction of the forefoot compresses the cuboid between the anterior surface of the calcaneus and the base of the fourth and fifth metatarsals. Patients will complain of indistinct pain in the area of the cuboid, and often present with swelling and ecchymosis. The diagnosis of cuboid fractures begins with plain radiographs. CT scans and MRIs are options if further detail about the fracture is needed. Cuboid fractures get classified into three main groups depending on location and complexity as per the Orthopedic Trauma Association. Treatment depends on fracture type and extent.[15][2]

Media

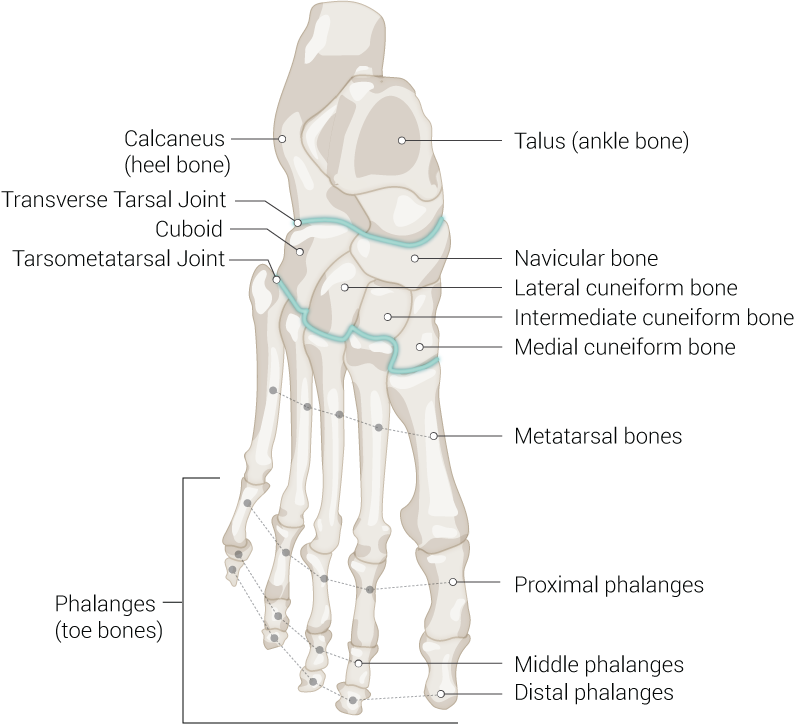

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Foot Bones. Anatomy of the foot including talus (ankle bone), navicular bone, lateral cuneiform bone, intermediate cuneiform bone, medial cuneiform bone, metatarsal bones, proximal phalanges, middle phalanges, distal phalanges, phalanges (toe bones), tarsometatarsal joint, cuboid, transverse tarsal joint, and calcaneus (heel bone).

Contributed by Beckie Palmer

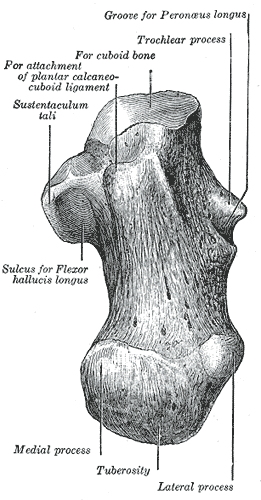

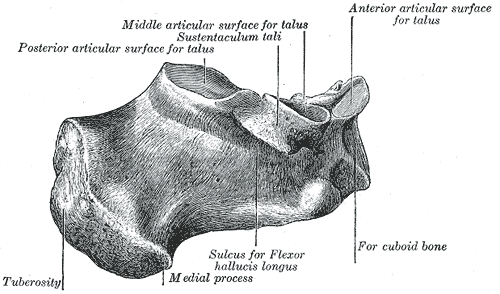

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Angoules AG, Angoules NA, Georgoudis M, Kapetanakis S. Update on diagnosis and management of cuboid fractures. World journal of orthopedics. 2019 Feb 18:10(2):71-80. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v10.i2.71. Epub 2019 Feb 18 [PubMed PMID: 30788224]

Pountos I, Panteli M, Giannoudis PV. Cuboid Injuries. Indian journal of orthopaedics. 2018 May-Jun:52(3):297-303. doi: 10.4103/ortho.IJOrtho_610_17. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29887632]

Patterson SM. Cuboid syndrome: a review of the literature. Journal of sports science & medicine. 2006 Dec 15:5(4):597-606 [PubMed PMID: 24357955]

Traister E, Simons S. Diagnostic considerations of lateral column foot pain in athletes. Current sports medicine reports. 2014 Nov-Dec:13(6):370-6. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0000000000000099. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25391092]

Yu SM, Dardani M, Yu JS. MRI of isolated cuboid stress fractures in adults. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2013 Dec:201(6):1325-30. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.10543. Epub 2013 Oct 22 [PubMed PMID: 24147421]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceVerbruggen SW, Nowlan NC. Ontogeny of the Human Pelvis. Anatomical record (Hoboken, N.J. : 2007). 2017 Apr:300(4):643-652. doi: 10.1002/ar.23541. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28297183]

Pazzaglia UE, Congiu T, Sibilia V, Pagani F, Benetti A, Zarattini G. Relationship between the chondrocyte maturation cycle and the endochondral ossification in the diaphyseal and epiphyseal ossification centers. Journal of morphology. 2016 Sep:277(9):1187-98. doi: 10.1002/jmor.20568. Epub 2016 Jun 16 [PubMed PMID: 27312928]

Borrelli J Jr, De S, VanPelt M. Fracture of the cuboid. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2012 Jul:20(7):472-7. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-20-07-472. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22751166]

Card RK, Bordoni B. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Foot Muscles. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30969527]

De Maeseneer M, Madani H, Lenchik L, Kalume Brigido M, Shahabpour M, Marcelis S, de Mey J, Scafoglieri A. Normal Anatomy and Compression Areas of Nerves of the Foot and Ankle: US and MR Imaging with Anatomic Correlation. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2015 Sep-Oct:35(5):1469-82. doi: 10.1148/rg.2015150028. Epub 2015 Aug 18 [PubMed PMID: 26284303]

Chari B, McNally E. Nerve Entrapment in Ankle and Foot: Ultrasound Imaging. Seminars in musculoskeletal radiology. 2018 Jul:22(3):354-363. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1648252. Epub 2018 May 23 [PubMed PMID: 29791963]

Desai SS, Cohen-Levy WB. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Tibial Nerve. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30725713]

Awan O, Graham JA. The rare cuboid-navicular coalition presenting as chronic foot pain. Case reports in radiology. 2015:2015():625285. doi: 10.1155/2015/625285. Epub 2015 Jan 26 [PubMed PMID: 25688320]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGarcía-Mata S, Hidalgo-Ovejero A. Cuboid-navicular tarsal coalition in an athlete. Anales del sistema sanitario de Navarra. 2011 May-Aug:34(2):289-92 [PubMed PMID: 21904410]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLau H, Dreyer MA. Cuboid Stress Fractures. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31194407]

Durall CJ. Examination and treatment of cuboid syndrome: a literature review. Sports health. 2011 Nov:3(6):514-9 [PubMed PMID: 23016051]