Introduction

The thyroid gland is a vital butterfly-shaped endocrine gland situated in the lower part of the neck. It is present in the front and sides of the trachea, inferior to the larynx. It plays an essential role in regulating the basal metabolic rate (BMR) and stimulates somatic and psychic growth, besides having a vital role in calcium metabolism.

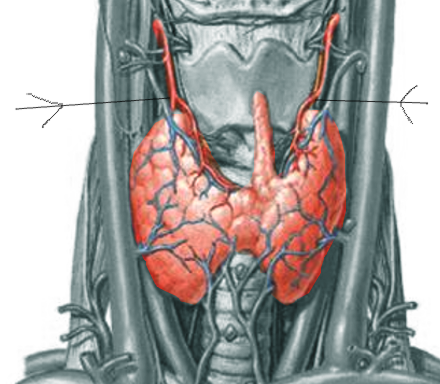

It is a gland consisting of two lobes, the right, and the left lobes, joined together by an intermediate structure, the isthmus. Sometimes a third lobe called the pyramidal lobe projects from the isthmus. It has a fibrous/fibromuscular band, i.e., levator glandulae thyroideae running from the body of the hyoid to the isthmus.[1] The lobes are 5 x 2.5 x 2.5 cm in dimension and weigh around 25 gm. It extends from the fifth cervical to the first thoracic vertebrae. The lobes extend from the middle of the thyroid cartilage to the fifth tracheal ring. The isthmus is 1.2 x 1.2 cm in dimensions and extends from second to third tracheal rings. It grows larger in females during the period of menstruation and pregnancy.

The lobes are conical in shape and have an apex, a base, three surfaces – lateral, medial, and posterolateral, and two borders – the anterior and posterior. The isthmus, however, has two surfaces – anterior and posterior and two borders – superior and inferior.

The lobes are related anteriorly to the skin, superficial and deep fascia, and platysma. Posteriorly, the lobes are associated with the laminae of the thyroid cartilage and tracheal rings and laterally to the external carotid artery and internal jugular vein.

The thyroid gland is a richly vascular organ supplied by the superior and inferior thyroid arteries and sometimes by an additional artery known as the thyroidea ima artery (see Image. The Thyroid Artery).[2] The venous drainage is by superior, middle, and inferior thyroid veins. Sometimes a fourth thyroid vein might be present, called the vein of Kocher. The nerve supply is mainly from middle cervical ganglion but also partly from superior and inferior cervical ganglions.

Two capsules completely cover the thyroid gland. The true capsule is made up of fibro-elastic connective tissue. The false capsule comprises the pre-tracheal layer of the deep cervical fascia. It consists of deep capillary plexus deep to the true capsule. Hence, it is crucial to remove the plexus with capsule during thyroidectomy.

Issues of Concern

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Issues of Concern

Nerves Related to the Thyroid Gland

The thyroid gland is close to two crucial nerves: the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve and the recurrent laryngeal nerve. Both are branches of the vagus nerve. During thyroidectomy, damage to these nerves leads to disability in phonation and/or difficulty in breathing. Injury to one of the branches of the superior laryngeal nerve leads to great difficulty in singing. Injury to the recurrent laryngeal nerve unilaterally may lead to hoarseness of the voice and difficulty in breathing. Bilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve injury is serious and often necessitates a tracheostomy.[3]

The thyroid gland is entirely covered by two capsules- true and false. The thyroid gland consists of deep capillary plexus deeper to the true capsule. This physical arrangement makes it crucial to remove the plexus with capsule during thyroidectomy.[4]

Structure

The thyroid gland is divided into lobules by the septae dipping from the capsule. The thyroid lobules consist of many typical units called thyroid follicles.[5] The thyroid follicles are the structural and functional units of a thyroid gland. These are spherical, and the wall is made up of a large number of cuboidal cells, the follicular cells. These follicular cells are the derivates of the endoderm and secrete thyroid hormone. The circulating form of this hormone is thyroxine, which is tetraiodothyronine (T4) along with a small quantity of triiodothyronine (T3). Even though most of T4 later converts to the more active form T3, both affect the target cells with varying degrees of stimulation. These hormones help in regulating the BMR of the body. In between these thyroid follicles or within the wall of the thyroid follicles, we find the small C cells, also known as Parafollicular cells. These are derived from neural crest cells and secrete polypeptide hormone known as calcitonin. The calcitonin helps deposit calcium and phosphate in skeletal and other tissues leading to hypocalcemia. This function is the opposite of the parathormone.

These thyroid follicles act as storage compartments filled with a substance called the colloid. This colloid is thyroglobulin, which is nothing but acidophilic secretory glycoprotein that is PAS-positive. These follicles are held together tightly within a delicate network of reticular fibers with an extensive capillary bed.

Function

Some of the essential functions of the thyroid hormones are as follows:

- They help in the overall growth, development, and differentiation of all the body cells.[6][7]

- They regulate the basal metabolic rate (BMR).

- They play an essential role in calcium metabolism

- They help in the overall development and function of CNS in children.[8]

- They stimulate somatic and psychic growth.

- They stimulate heart rate and contraction.[9]

- They help in the deposition of calcium and phosphate in bone and make the bones strong.

- They decrease the level of calcium in the blood.

- They regulate carbohydrate, fat, and protein metabolism.

- They also help in the metabolism of vitamins.

- They control the body temperature.

- They help degrade cholesterol and triglycerides.

- They maintain the electrolyte balance.

- They support the process of RBC formation.

- They enhance mitochondrial metabolism.

- They increase the oxygen consumptions by the cells and tissues.

- They influence the mood and behavior of a person.[10]

- They stimulate gut motility.[11]

- They also enhance the sensitivity of the beta-adrenergic receptors to catecholamines.

Thus the thyroid hormones act on almost all the cells of the body. They also take up a vital role in the development, growth, and function of most of the tissues and organs of the body. One can also say that the thyroid hormones are mandatory for the normal metabolic activity of all the cells of the body.

Tissue Preparation

Tissue preparation for immunohistochemistry requires surgically resecting the thyroid lesions. The preparation of thyroid samples includes fixation using 10% zinc formalin, after which the tissue requires embedding in paraffin. The embedding protocols vary according to the substrate, whether the protocol uses a chromogenic or fluorescent substrate. Paraffin embedding provides an option for the long-term preservation of tissues. The tissues must not be left to fix for more than 24 hours because over fixation could cause mask the antigen. If necessary, tissues can get transferred to alcohol following fixation before the embedding process. Contrarily, the tissues can be frozen instead of fixing. Snap freezing is usually done to detect post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation, nitration, etc. Tissue freezing can be done by immersing tissues in liquid nitrogen or isopentane or by snap freezing in dry ice. Frozen tissue sections require alcohol fixing. This process avoids the need to retrieve epitopes that get masked by the formaldehyde/ formalin fixing method.

Next, the embedded sections get cut using a microtome. Usually, 4mm thick sections provide accurate staining with hematoxylin and eosin for routine histological examination. For immunohistochemical staining, separate areas are used and stained with selected markers. Immunostaining requires precise experimental conditions to generate a strong and specific immunohistochemical staining for each antigen of interest.

For Immunocytochemical staining, the thyroid cells from the lesion or fine-needle aspiration specimens are transferred and attached to a solid support, usually a microscope slide or coverslip. The use of pre-coated coverslip with poly-L-lysine and/or an extracellular matrix protein such as laminin, fibronectin, or collagen enhances the attachment of thyroid tissue cells. Air-dried smear preparation is with a Romanovsky stain. Wetfixed smears are usually prepared with a modified Papanicolaou stain and used to observe nuclear detail. MayGrünwald-Giemsa is a staining procedure also used in thyroid cytologic preparations.[12]

Histochemistry and Cytochemistry

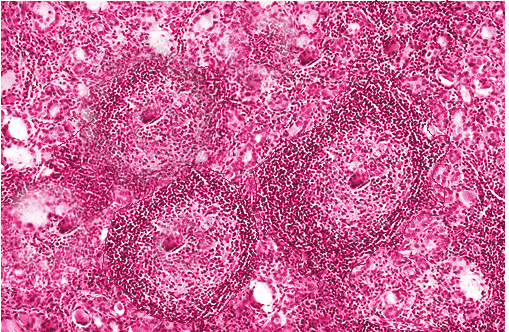

Cytochemical techniques are essential for diagnosing thyroid lesions of the thyroid gland pathologies (see Image. Hashimoto Thyroiditis). Direct and indirect immunofluorescence techniques are helpful to localize the thyroid hormones tri-iodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4). The techniques manipulate the specificity of antibodies for T3 or T4, which gives enhanced fluorescence for the apical cytoplasm of follicular cells and the colloid pools, indicating thyroglobulin. The technique is specific for the thyroid gland and does not stain the adjacent gland.[13] Histochemical analyses of the patterns of activity and localization of 5-nucleotidase (CD73) through the use of anti-5' nucleotidase ecto antibody in the thyroid gland provide valuable insight into several pathologies associated with the thyroid gland. The activity of the enzyme is increased in papillary thyroid cancer (PTC). Monitoring the expression patterns is used to observe tumor size and lymph node metastasis in PTC. Additionally, the sites of localization of this enzyme also indicate cell transport mechanisms.[14]

Other enzyme-based histochemical reactions utilized to monitor thyroid functions are adenosine triphosphatase, alkaline and acid phosphatases, galectin-3, and alpha-naphthyl acetate esterase. Papillary and follicular carcinomas, as well as Graves disease, show positive staining for adenosine triphosphatase. The reaction distinguishes between benign and malignant neoplasms of the thyroid epithelium in humans. The benign neoplasms are positive for 5'-nucleotidase, alpha-naphthyl acetate esterase, and acid phosphatase and negative for alkaline phosphatase and adenosine triphosphatase. Histochemical assessment of FoxA1 expression in C cells and its absence in follicular cells is a method to detect medullary thyroid carcinomas. FoxA1 expression has also been suggested as a potential oncogene testing in anaplastic thyroid carcinomas.[15] Similarly, GAL-3 expression shows a focal expression pattern in benign lesions and diffused expression in malignant lesions.[16] Immunohistochemistry staining pattern for intrathyroidal cancer-to-cancer metastasis within a non-neoplastic thyroid gland, a sporadic feature, is also precisely discernable with histochemical techniques. Immunohistochemical staining with CD10, renal cell carcinoma (RCC) marker, mammaglobin, estrogen receptor (ER), thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1), and thyroglobulin could provide an insight into the origin (renal or breast) of the metastatic carcinoma.[17]

Normal follicular epithelium of the thyroid gland shows no detectable CK19 expression, while in PTC, it gets overexpressed. Hence, cytokeratin 19 could be a good immunomarkers for diagnosing PTC. Monitoring the upregulation or downregulation of specific cell adhesion molecules (E-cadherin, fibronectin), cell cycle regulatory proteins (CD44, p27Kip1), and oncogenes (BRAF) through cytochemical staining are helpful techniques to test thyroid cancers.[18]

Many classical cytochemical techniques still hold significance in the analyses of thyroid pathologies. Localization of endogenous thyroperoxidase in thyroid follicles acts as an indicator of iodination during the synthesis of the thyroid hormones. Cytochemical staining of C and oxyphil cells serve as diagnostic markers for tumor, teratoma, and cyst formation in the thyroid gland.[19]

Microscopy, Light

Capsules of Thyroid

Two capsules entirely cover the thyroid gland.

- True – peripheral condensation of the glandular tissue

- False – the pre-tracheal layer of deep cervical fascia

The gland is surrounded by a thin fibro-elastic (true) capsule. This capsule, in turn, is covered by a pre-tracheal fascia from the outside and acts as a false capsule. The true capsule gives rise to septa deep into the parenchyma dividing the gland into lobules. The septa give passage for the blood vessels, nerves, and lymphatics into the gland.

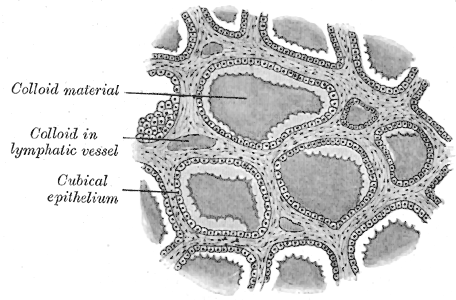

Each lobule is made of aggregation of follicles, which are the structural and functional units of the thyroid gland. The follicles are lined by follicular cells (simple) that rest on the basement membrane and have a cavity filled with a homogenous gelatinous material called the colloid. See Image. The Ductless Glands. The collide is composed of thyroglobulin, an iodinated glycoprotein, which is an inactive storage form of thyroid hormone.[20] The space between the follicles is filled with connective tissue stroma, numerous capillaries, and lymphatics. It is the only endocrine gland whose secretory products are stored in such great quantity and that too extracellularly. Inbetween the follicles are the parafollicular cells, also known as C-cells.

Follicular Cells

The follicular cells are the lining cells of a thyroid follicle. They vary in size, depending on the activity. When the follicles are in the resting (inactive) stage, the follicular cells are flat simple squamous, with abundant collide within the cavity.[21] When the follicles are highly active, the follicular cells are simple columnar with scanty collide. In a normal state of follicles during moderate activity, the cells are simple cuboidal, and the cavity is filled with a reasonable amount of colloid. But it is also possible for different cells to show different levels of activity within the same thyroid tissue.[22]

They secrete two hormones that influence the rate of metabolism[23]:

- T3 (tri-iodothyronine) and

- T4 (tetra-iodothyronine or thyroxine)

T3 is more active than T4, even though both affect the target cells.

EM features: Electron microscopy of follicular cells shows apical microvilli, abundant granular endoplasmic reticulum, supranuclear Golgi complex, lysosomes, microtubules, and microfilaments. The activity of these cells is influenced by thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) secreted by hypophysis cerebri.[24][25]

Parafollicular Cells (C–cells)

These are also known as clear cells or light cells. The C stands for calcitonin or clear.[26] These are large, polyhedral, pale-staining cells with oval and eccentric nuclei. They are widely distributed between follicular cells and their basement membrane. They also lie between adjoining follicular cells but do not reach the lumen. But in some species, they are also seen between the follicles in connective tissue in groups. They secrete a hormone known as calcitonin.[27][28] The secretion of this hormone is independent of hypophysis cerebri and mainly depends on the level of serum calcium.[29]

EM features: When seen under the electron microscope, the C-cells are visibly filled with electron-dense secretory granules (100 to 200 nm in diameter) of hormone calcitonin. The action of calcitonin is antagonistic to that of the parathyroid hormone. It lowers serum calcium by suppressing bone resorption by inhibiting osteoclastic activity and stimulating osteoblastic activity.[30]

Pathophysiology

The follicular cells take up the iodinated thyroglobulins from the colloid present within the lumen of the thyroid follicle. This process is under the influence of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). Afterward, lysosomal digestion and intracellular proteolysis release the thyroid hormone in the form of T3 and T4. These amino acid derivates are so small that they can easily escape the follicular cells and enter the bloodstream through fenestrations present in the capillaries.

The thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) secreted by the anterior pituitary gland affects not only the changes in the follicular cells but also the thyroid follicles and the activity of the gland itself. TSH stimulation occurs when there is a low iodine level in the diet by a negative feedback mechanism on pituitary thyrotrophs. TSH increases the size of the follicular cells (hypertrophy) and increases the number of follicular cells (hyperplasia). Thus under the influence of the TSH, the follicular cells become tall and columnar, demonstrating the heavy activity of the follicular cells and the follicles. The TSH also enhances the exocytosis, synthesis, and iodination of thyroglobulin. It also enhances endocytosis and intracellular breakdown of colloid. Thus the intraluminal colloid is greatly reduced, which manifests externally by the enlargement of the thyroid gland. Usually, enlargement of the thyroid gland is called goiter, which is a diseased state. But in this condition, the enlargement of the thyroid gland is because of the hypertrophy and hyperplasia of the parenchyma. Hence it is called parenchymatous goiter.[31] This condition differentiates from another type of goiter where the enlargement is not because of the hypertrophy and hyperplasia of the parenchyma but due to an increase in the production of colloid within the thyroid follicle. This condition is known as colloid goiter.[32][33] If this condition becomes longstanding with recurrent stages of hyperplasia and involution, it leads to a more irregular enlargement as a multinodular goiter [34]. They later also show fibrosis, calcification, cystic changes, and hemorrhagic spots.

If there is no stimulation of TSH, it leads to a decrease in the size of follicular cells to the cuboidal and later squamous cells.

In Graves's disease, the follicular cells are tall, columnar, and overcrowded, resulting in small papillae formation. These papillae will project into the follicular lumen. The colloid is pale and shows scalloped margins. The interstitium becomes infiltrated with T lymphocytes.

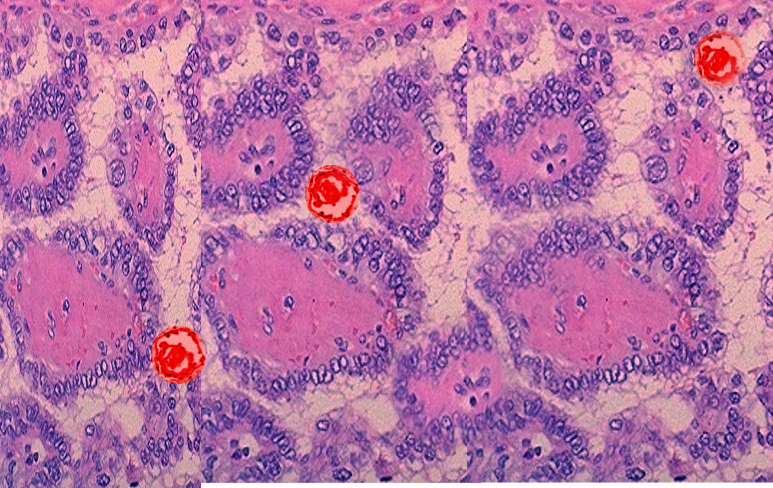

In the case of adenoma, the follicular cells are uniform and contain colloid in the lumen. They show atypia and prominent nucleoli and focal nuclear pleomorphism. They are well encapsulated in an intact capsule, which distinguishes them from follicular carcinoma. The papillary carcinoma shows typical "Orphan Annie eye" nuclei, which are due to finely dispersed chromatin.[35][34] It also shows a papillary architecture with the papillae and psammoma bodies (calcified concentric structures).[36][37] See Image. Papillary Thyroid Cancer, Psammoma Bodies. The cytoplasm of follicular cells also shows invaginations, which give an intranuclear inclusions-like appearance. Anaplastic carcinomas present themselves with large, pleomorphic giant cell lesions, spindle cells, etc.

The parafollicular cells secrete calcitonin whenever the plasma calcium level exceeds its normal limit. The target site for calcitonin in the bone is the osteoclast cells, thus reducing their number and action. Calcitonin also promotes the excretion of phosphate and calcium through urine. No significant clinical manifestations have been observed due to an increase or decrease of calcitonin, and hence, its role in humans is debatable. In parathyroid adenomas, the predominant cells will be chief cells, with few nests of oxyphil cells.[27] The chief cells are larger and show variability in nuclear size compared to the normal. Some cells also show bizarre and pleomorphic nuclei. Parathyroid carcinomas are difficult to distinguish from adenomas based on microscopic features, and hence only local and metastatic features are conclusive in making a diagnosis.

Clinical Significance

Goiter: It is a condition where the thyroid gland shows an abnormal enlargement. Goiters are broadly classified into uni-nodular, multinodular, and diffuse types. Each further includes many different types of goiters. Some of the commonest with some of their important features are described below.[38][39]

Colloid nodular goiter: This is the commonest of the non-neoplastic lesions of the thyroid.[38] In these types of goiter, the thyroid follicles are filled with an abundant amount of colloid in their lumens and lined by squamous follicular cells.

Hyperthyroidism (Thyrotoxicosis): It is a condition of hypermetabolic state and hyperfunctioning of the thyroid gland resulting in increased T3 and T4 levels. Some symptoms included palpitations, tachycardia, nervousness, etc.

Graves disease: This disease is a combination of thyrotoxicosis, exophthalmos, and dermopathy (myxedema). It is especially seen in women in the age group of 20 to 40 years, manifesting in the form of prolonged and violent palpitations.

Hypothyroidism: This condition develops due to any functional and structural derangement that leads to decreased thyroid hormone production. This condition clinically manifests as cretinism in infants and myxoedema in adults. Cretinism patients present themselves as short-statured, with coarse facial features, mental retardation, protruding tongue, etc.

Thyroid cancer: Thyroid carcinomas arise either from the follicular epithelium or parafollicular C-cells. They are painless nodules and compression, displacing the adjacent structures. The carcinomas of the thyroid can manifest in the form of papillary carcinoma, follicular carcinoma, anaplastic carcinoma, and medullary carcinoma.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

The Ductless Glands. The image shows a section of a sheep's thyroid gland, colloid material, colloid in a lymphatic vessel, and cubical epithelium.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Chaudhary P, Singh Z, Khullar M, Arora K. Levator glandulae thyroideae, a fibromusculoglandular band with absence of pyramidal lobe and its innervation: a case report. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research : JCDR. 2013 Jul:7(7):1421-4. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2013/6144.3186. Epub 2013 Jul 1 [PubMed PMID: 23998080]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceEsen K, Ozgur A, Balci Y, Tok S, Kara E. Variations in the origins of the thyroid arteries on CT angiography. Japanese journal of radiology. 2018 Feb:36(2):96-102. doi: 10.1007/s11604-017-0710-3. Epub 2017 Dec 4 [PubMed PMID: 29204764]

Giulea C, Enciu O, Toma EA, Calu V, Miron A. The Tubercle of Zuckerkandl is Associated with Increased Rates of Transient Postoperative Hypocalcemia and Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve Palsy After Total Thyroidectomy. Chirurgia (Bucharest, Romania : 1990). 2019 Sept-Oct:114(5):579-585. doi: 10.21614/chirurgia.114.5.579. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31670633]

Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, Boyce A, Chrousos G, Corpas E, de Herder WW, Dhatariya K, Dungan K, Hofland J, Kalra S, Kaltsas G, Kapoor N, Koch C, Kopp P, Korbonits M, Kovacs CS, Kuohung W, Laferrère B, Levy M, McGee EA, McLachlan R, New M, Purnell J, Sahay R, Shah AS, Singer F, Sperling MA, Stratakis CA, Trence DL, Wilson DP, Kaplan E, Angelos P, Applewhite M, Mercier F, Grogan RH. Chapter 21 SURGERY OF THE THYROID. Endotext. 2000:(): [PubMed PMID: 25905419]

Rykova Y, Shuper S, Shcherbakovsky M, Kikinchuk V, Peshenko A. [MORPHOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE THYROID GLAND OF MATURE RATS IN MODERATE DEGREE CHRONIC HYPERTHERMIA]. Georgian medical news. 2019 Jul-Aug:(292-293):75-81 [PubMed PMID: 31560668]

Hofstee P, Bartho LA, McKeating DR, Radenkovic F, McEnroe G, Fisher JJ, Holland OJ, Vanderlelie JJ, Perkins AV, Cuffe JSM. Maternal selenium deficiency during pregnancy in mice increases thyroid hormone concentrations, alters placental function and reduces fetal growth. The Journal of physiology. 2019 Dec:597(23):5597-5617. doi: 10.1113/JP278473. Epub 2019 Oct 30 [PubMed PMID: 31562642]

Talat A, Khan AA, Nasreen S, Wass JA. Thyroid Screening During Early Pregnancy and the Need for Trimester Specific Reference Ranges: A Cross-Sectional Study in Lahore, Pakistan. Cureus. 2019 Sep 15:11(9):e5661. doi: 10.7759/cureus.5661. Epub 2019 Sep 15 [PubMed PMID: 31720137]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceZhu B, Zhao G, Yang L, Zhou B. Tetrabromobisphenol A caused neurodevelopmental toxicity via disrupting thyroid hormones in zebrafish larvae. Chemosphere. 2018 Apr:197():353-361. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.01.080. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29407805]

Delitala AP, Scuteri A, Maioli M, Mangatia P, Vilardi L, Erre GL. Subclinical hypothyroidism and cardiovascular risk factors. Minerva medica. 2019 Dec:110(6):530-545. doi: 10.23736/S0026-4806.19.06292-X. Epub 2019 Nov 11 [PubMed PMID: 31726814]

Tost M, Monreal JA, Armario A, Barbero JD, Cobo J, García-Rizo C, Bioque M, Usall J, Huerta-Ramos E, Soria V, PNECAT Group, Labad J. Targeting Hormones for Improving Cognition in Major Mood Disorders and Schizophrenia: Thyroid Hormones and Prolactin. Clinical drug investigation. 2020 Jan:40(1):1-14. doi: 10.1007/s40261-019-00854-w. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31612424]

Lee JH, Kwon OD, Ahn SH, Choi KH, Park JH, Lee S, Choi BK, Jung KY. Reduction of gastrointestinal motility by unilateral thyroparathyroidectomy plus subdiaphragmatic vagotomy in rats. World journal of gastroenterology. 2012 Sep 7:18(33):4570-7. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i33.4570. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22969231]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFeingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, Boyce A, Chrousos G, Corpas E, de Herder WW, Dhatariya K, Dungan K, Hofland J, Kalra S, Kaltsas G, Kapoor N, Koch C, Kopp P, Korbonits M, Kovacs CS, Kuohung W, Laferrère B, Levy M, McGee EA, McLachlan R, New M, Purnell J, Sahay R, Shah AS, Singer F, Sperling MA, Stratakis CA, Trence DL, Wilson DP, Jasim S, Dean DS, Gharib H. Fine-Needle Aspiration of the Thyroid Gland. Endotext. 2000:(): [PubMed PMID: 25905400]

Keenan DM, Pichler Hefti J, Veldhuis JD, Von Wolff M. Regulation and adaptation of endocrine axes at high altitude. American journal of physiology. Endocrinology and metabolism. 2020 Feb 1:318(2):E297-E309. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00243.2019. Epub 2019 Nov 26 [PubMed PMID: 31770013]

Bertoni APS, de Campos RP, Tsao M, Braganhol E, Furlanetto TW, Wink MR. Extracellular ATP is Differentially Metabolized on Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma Cells Surface in Comparison to Normal Cells. Cancer microenvironment : official journal of the International Cancer Microenvironment Society. 2018 Jun:11(1):61-70. doi: 10.1007/s12307-018-0206-4. Epub 2018 Feb 17 [PubMed PMID: 29455338]

Nonaka D. A study of FoxA1 expression in thyroid tumors. Human pathology. 2017 Jul:65():217-224. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2017.05.007. Epub 2017 May 22 [PubMed PMID: 28546130]

Dunđerović D, Lipkovski JM, Boričic I, Soldatović I, Božic V, Cvejić D, Tatić S. Defining the value of CD56, CK19, Galectin 3 and HBME-1 in diagnosis of follicular cell derived lesions of thyroid with systematic review of literature. Diagnostic pathology. 2015 Oct 26:10():196. doi: 10.1186/s13000-015-0428-4. Epub 2015 Oct 26 [PubMed PMID: 26503236]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWong YP, Affandi KA, Tan GC, Muhammad R. Metastasis within a metastasis to the thyroid: A rare phenomenon. Indian journal of pathology & microbiology. 2017 Jul-Sep:60(3):430-432. doi: 10.4103/IJPM.IJPM_287_16. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28937391]

Naoum GE, Morkos M, Kim B, Arafat W. Novel targeted therapies and immunotherapy for advanced thyroid cancers. Molecular cancer. 2018 Feb 19:17(1):51. doi: 10.1186/s12943-018-0786-0. Epub 2018 Feb 19 [PubMed PMID: 29455653]

Kalfert D, Ludvikova M, Kholova I, Ludvik J, Topolocan O, Plzak J. Combined use of galectin-3 and thyroid peroxidase improves the differential diagnosis of thyroid tumors. Neoplasma. 2020 Jan:67(1):164-170. doi: 10.4149/neo_2019_190128N86. Epub 2019 Nov 18 [PubMed PMID: 31777257]

Lee J, Yi S, Kang YE, Kim HW, Joung KH, Sul HJ, Kim KS, Shong M. Morphological and Functional Changes in the Thyroid Follicles of the Aged Murine and Humans. Journal of pathology and translational medicine. 2016 Nov:50(6):426-435 [PubMed PMID: 27737529]

Petrova I, Mitevska E, Gerasimovska Z, Milenkova L, Kostovska N. Histological structure of the thyroid gland in apolipoprotein E deficient female mice after levothyroxine application. Prilozi (Makedonska akademija na naukite i umetnostite. Oddelenie za medicinski nauki). 2014:35(3):135-40 [PubMed PMID: 25725701]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceShoyele O, Bacus B, Haddad L, Li Y, Shidham V. Lymphoproliferative process with reactive follicular cells in thyroid fine-needle aspiration: A few simple but important diagnostic pearls. CytoJournal. 2019:16():20. doi: 10.4103/cytojournal.cytojournal_5_19. Epub 2019 Oct 22 [PubMed PMID: 31741667]

Ibhazehiebo K, Koibuchi N. Temporal effects of thyroid hormone (TH) and decabrominated diphenyl ether (BDE209) on Purkinje cell dendrite arborization. Nigerian journal of physiological sciences : official publication of the Physiological Society of Nigeria. 2012 Jun 7:27(1):11-7 [PubMed PMID: 23235302]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTakizawa T, Yamamoto M, Arishima K, Kusanagi M, Somiya H, Eguchi Y. An electron microscopic study on follicular formation and TSH sensitivity of the fetal rat thyroid gland in organ culture. The Journal of veterinary medical science. 1993 Feb:55(1):157-60 [PubMed PMID: 8461414]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRajkovic V, Matavulj M, Johansson O. Light and electron microscopic study of the thyroid gland in rats exposed to power-frequency electromagnetic fields. The Journal of experimental biology. 2006 Sep:209(Pt 17):3322-8 [PubMed PMID: 16916968]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceShah JP. Thyroid carcinoma: epidemiology, histology, and diagnosis. Clinical advances in hematology & oncology : H&O. 2015 Apr:13(4 Suppl 4):3-6 [PubMed PMID: 26430868]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMcLaughlin MB, Awosika AO, Jialal I. Calcitonin. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30725954]

Felsenfeld AJ, Levine BS. Calcitonin, the forgotten hormone: does it deserve to be forgotten? Clinical kidney journal. 2015 Apr:8(2):180-7. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfv011. Epub 2015 Mar 20 [PubMed PMID: 25815174]

Sexton PM, Findlay DM, Martin TJ. Calcitonin. Current medicinal chemistry. 1999 Nov:6(11):1067-93 [PubMed PMID: 10519914]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKameda Y. Electron microscopic studies on the parafollicular cells and parafollicular cell complexes in the dog. Archivum histologicum Japonicum = Nihon soshikigaku kiroku. 1973 Dec:36(2):89-105 [PubMed PMID: 4360770]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYildirim D, Alis D, Bakir A, Ustabasioglu FE, Samanci C, Colakoglu B. Evaluation of parenchymal thyroid diseases with multiparametric ultrasonography. The Indian journal of radiology & imaging. 2017 Oct-Dec:27(4):463-469. doi: 10.4103/ijri.IJRI_409_16. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29379243]

Albasri A, Sawaf Z, Hussainy AS, Alhujaily A. Histopathological patterns of thyroid disease in Al-Madinah region of Saudi Arabia. Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention : APJCP. 2014:15(14):5565-70 [PubMed PMID: 25081665]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceQureshi IA, Khabaz MN, Baig M, Begum B, Abdelrehaman AS, Hussain MB. Histopathological findings in goiter: A review of 624 thyroidectomies. Neuro endocrinology letters. 2015:36(1):48-52 [PubMed PMID: 25789588]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDeLellis RA. Orphan Annie eye nuclei: a historical note. The American journal of surgical pathology. 1993 Oct:17(10):1067-8 [PubMed PMID: 8372945]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBavle RM. Orphan annie-eye nuclei. Journal of oral and maxillofacial pathology : JOMFP. 2013 May:17(2):154-5. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.119737. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24250070]

Das DK. Psammoma body: a product of dystrophic calcification or of a biologically active process that aims at limiting the growth and spread of tumor? Diagnostic cytopathology. 2009 Jul:37(7):534-41. doi: 10.1002/dc.21081. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19373908]

Pyo JS, Kang G, Kim DH, Park C, Kim JH, Sohn JH. The prognostic relevance of psammoma bodies and ultrasonographic intratumoral calcifications in papillary thyroid carcinoma. World journal of surgery. 2013 Oct:37(10):2330-5. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-2107-5. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23716027]

Chaudhary M, Baisakhiya N, Singh G. Clinicopathological and Radiological Study of Thyroid Swelling. Indian journal of otolaryngology and head and neck surgery : official publication of the Association of Otolaryngologists of India. 2019 Oct:71(Suppl 1):893-904. doi: 10.1007/s12070-019-01616-y. Epub 2019 Feb 8 [PubMed PMID: 31742091]

Gurleyik E. Recurrent Goiter Presented with Marine-Lenhart Syndrome 27 Years After Initial Surgery. Cureus. 2019 Sep 26:11(9):e5768. doi: 10.7759/cureus.5768. Epub 2019 Sep 26 [PubMed PMID: 31723527]